The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial Owner and publisher: In 2019, the City of Vienna introduced in society. Thus, their feedback was Vienna City Administration the Werkstadt Junges Wien project, a taken very seriously and provided the unique large-scale participation pro- basis for the definition of nine goals Project coordinators: cess to develop a strategy for children under the Children and Youth Stra- Bettina Schwarzmayr and Alexandra Beweis and young people with the aim of tegy. Now, Vienna is for the first time Management team of the Werkstadt Junges Wien project at the Municipal Department for Education and Youth giving more room to the requirements bundling efforts from all policy areas, in cooperation with wienXtra, a young city programme promoting children, young people and families of Vienna’s young residents. The departments and enterprises of the “assignment” given to the children city and is aligning them behind the Contents: and young people participating in shared vision of making the City of The contents were drafted on the basis of the wishes, ideas and concerns of more than 22,500 children and young the project was to perform a “service Vienna a better place for all children people in consultation with staff of the Vienna City Administration, its associated organisations and enterprises check” on the City of Vienna: What and young people who live in the city. and other experts as members of the theme management groups in the period from April 2019 to December 2019; is working well? What is not working responsible for the content: Karl Ceplak, Head of Youth Department of the Province of Vienna well? Which improvements do they The following strategic plan presents suggest? The young participants were the results of the Werkstadt Junges Design and layout: entirely free to choose the issues they Wien project and outlines the goals Die Mühle - Visual Studio wanted to address. -

Introduction Podge of Half-Anonymous Nationalities and Clumsily Struggling Against the Fresh, Ambitious, and Apparently Victorious Idea of Nationalism

IN TRODUCTION ustria-Hungary ceased to exist almost a hundred years ago. The A oldest generation of Central Europeans can remember it from their parents’ and grandparents’ stories. The majority of them learned about it in high school and associates the monarchy with its few roy- als, particularly the late Franz Joseph and his eccentric wife Elisabeth. Those figures, already famous during their lifetime, entered the realm of popular culture and remain recognizable in most countries of Eu- rope, providing a stable income for the souvenir industry in what used to be their empire and inspiration for screenwriters on both sides of the Atlantic. Naturally, the situation varies from country to country as far as history textbooks and historical monuments are concerned. Thus, Austrians and Hungarians are generally more familiar with the monarchy than are the Germans or Poles, not to mention the British and French, whereas Serbs, Italians, Czechs, and Romanians tend to be highly suspicious of it. The old monarchy also built quite well, so modern travelers who wish to see what is left of the Habsburg em- pire do not need to limit their curiosity to imperial residences, nor to the opera houses in cities such as Prague, Lviv, and Zagreb. In most cities of former Austria-Hungary, visitors can get acquainted with Habsburg architecture at the railway station. In this respect Vienna, heavily bombed by the Anglo-American air forces and the Soviet artil- lery during World War II, is merely a sad exception. Other traces of the 1 imperial past can still be discovered in many private apartments, an- tique shops, and retro-style cafés, in cemeteries, and old photographs. -

Sources for Genealogical Research at the Austrian War Archives in Vienna (Kriegsarchiv Wien)

SOURCES FOR GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE AUSTRIAN WAR ARCHIVES IN VIENNA (KRIEGSARCHIV WIEN) by Christoph Tepperberg Director of the Kriegsarchiv 1 Table of contents 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives 1.2. Conditions for doing genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. Sources for genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. 1. Documents of the military administration and commands 2. 2. Personnel records, and records pertaining to personnel 2.2.1. Sources for research on military personnel of all ranks 2.2.2. Sources for research on commissioned officers and military officials 3. Using the Archives 3.1. Regulations for using personnel records 3.2. Visiting the Archives 3.3. Written inquiries 3.4. Professional researchers 4. Relevant publications 5. Sources for genealogical research in other archives and institutions 5.1. Sources for genealogical research in other departments of the Austrian State Archives 5.2. Sources for genealogical research in other Austrian archives 5.3. Sources for genealogical research in archives outside of Austria 5.3.1. The provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and its “successor states” 5.3.2. Sources for genealogical research in the “successor states” 5.4. Additional points of contact and practical hints for genealogical research 2 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives Today’s Austrian Republic is a small country, but from 1526 to 1918 Austria was a great power, we can say: the United States of Middle and Southeastern Europe. -

Footpath Description

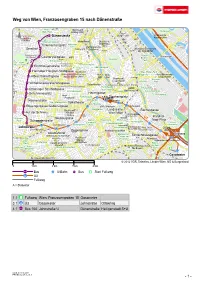

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

Notes of Michael J. Zeps, SJ

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 1-1-2011 Documents of Baudirektion Wien 1919-1941: Notes of Michael J. Zeps, S.J. Michael J. Zeps S.J. Marquette University, [email protected] Preface While doing research in Vienna for my dissertation on relations between Church and State in Austria between the wars I became intrigued by the outward appearance of the public housing projects put up by Red Vienna at the same time. They seemed to have a martial cast to them not at all restricted to the famous Karl-Marx-Hof so, against advice that I would find nothing, I decided to see what could be found in the archives of the Stadtbauamt to tie the architecture of the program to the civil war of 1934 when the structures became the principal focus of conflict. I found no direct tie anywhere in the documents but uncovered some circumstantial evidence that might be explored in the future. One reason for publishing these notes is to save researchers from the same dead end I ran into. This is not to say no evidence was ever present because there are many missing documents in the sequence which might turn up in the future—there is more than one complaint to be found about staff members taking documents and not returning them—and the socialists who controlled the records had an interest in denying any connection both before and after the civil war. Certain kinds of records are simply not there including assessments of personnel which are in the files of the Magistratsdirektion not accessible to the public and minutes of most meetings within the various Magistrats Abteilungen connected with the program. -

From Oppression to Freedom

FROM OPPRESSION TO FREEDOM John Jay and his Huguenot Heritage The Protestant Reformation changed European history, when it challenged the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century. John Calvin was a French theologian who led his own branch of the movement. French Protestants were called Huguenots as a derisive Conflict Over the term by Catholics. Protestant Disagreements escalated into a series of religious wars Reformation in seventeenth-century France. Tens of thousands of Huguenots were killed. Finally, the Edict of Nantes was issued in 1598 to end the bloodshed; it established Catholicism as the official religion of France, but granted Protestants the right to worship in their own way. Eighty-seven years later, in 1685, King Louis XIV issued the Edict of Fontainebleau, which reversed the Edict of Nantes, and declared the public practice of Protestantism illegal. Louis regarded religious pluralism as an obstacle to his achieving complete power over the French people. By his order, Huguenot churches were demolished, Huguenot schools were The Revocation of closed, all newborns were required to be baptized as Roman Catholics, and it became illegal for the the Edict of Nantes Protestant laity to emigrate or remove their valuables from France. A View of La Rochelle In La Rochelle, a busy seaport on France’s Atlantic coast, the large population of Huguenot merchants, traders, and artisans there suffered the persecution that followed the edict. Among them was Pierre Jay, an affluent trader, and his family. Pierre’s church was torn down. In order to intimidate him into converting to Catholicism, the government quartered unruly soldiers called dragonnades in his house, to live with him and his family. -

VIENNA UNIVERSITY of TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Gusshausstrasse 28 / 1St Floor, A-1040 Wien

VIENNA UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Gusshausstrasse 28 / 1st floor, A-1040 Wien Contact: Tel: +43 (0)1 58801 - 41550 / 41552 Fax: +43 (0)1 58801 - 41599 Email: [email protected] ANKUNFT http://www.tuwien.ac.at/international Opening hours: Monday, Thursday: 9:30 a.m. – 11:30 a.m., 1:30 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. Wednesday: 9:30 a.m. – 11:30 a.m. How to reach us: Metro: U1 (Station Taubstummengasse) U2 (Station Karlsplatz) U4 (Station Karlsplatz) Tram: Line 62 (Station Paulanergasse) Line 65 (Station Paulanergasse) Line 71 (Station Schwarzenbergplatz) Welcome Guide TU Wien │ 1 Published by: International Office of Vienna University of Technology Gusshausstrasse 28 A-1040 Wien © 2014 Print financed by funds of the European Union 2 │ Welcome Guide TU Wien CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT TU WIEN .............................................. 5 1 History of Vienna University of Technology ......................................... 5 2 Structure of Vienna University of Technology ...................................... 6 3 Fields of Study ..................................................................................... 7 4 The Austrian National Union of Students ........................................... 11 PLANNING IN YOUR HOME COUNTRY..................................................... 13 1 Applying for Studies at TU Wien ........................................................ 13 2 Visa ....................................................................................................13 3 Linguistic Requirements .................................................................... -

Jewish Communities of Leopoldstadt and Alsergrund

THE VIENNA PROJECT: JEWISH COMMUNITIES OF LEOPOLDSTADT AND ALSERGRUND Site 1A: Introduction to Jewish Life in Leopoldstadt Leopoldstadt, 1020 The history of Jews in Austria is one of repeated exile (der Vertreibene) and return. In 1624, after years and years of being forbidden from living in Vienna, Emperor Ferdinand III decided that Jewish people could return to Vienna but would only be allowed to live in one area outside of central Vienna. That area was called “Unterer Werd” and later became the district of Leopoldstadt. In 1783, Joseph II’s “Toleranzpatent” eased a lot of the restrictions that kept Jews from holding certain jobs or owning homes in areas outside of Leopoldstadt. As a result, life in Vienna became much more open and pleasant for Jewish people, and many more Jewish immigrants began moving to Vienna. Leopoldstadt remained the cultural center of Jewish life, and was nicknamed “Mazzeinsel” after the traditional Jewish matzo bread. Jews made up 40% of the people living in the 2nd district, and about 29% of the city’s Jewish population lived there. A lot of Jewish businesses were located in Leopoldstadt, as well as many of the city’s synagogues and temples. Tens of thousands of Galician Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe made their home there, and brought many of their traditions (such as Yiddish literature) with them. Questions to Consider Look up the history of Jewish eXile and return in Vienna. How many times were they sent away from the city, and why did the city let them return? What were some of the restrictions on Jewish life in Vienna before the “Toleranzpatent” in 1783? What further rights did Jewish people gain in 1860? How did this affect Jewish life and culture in Vienna in the late 1800s and early 1900s? Describe the culture of Leopoldstadt before 1938. -

Das Vermächtnis Der Eugenie

Buchpräsentation Testamentseröffnung: Das Vermächtnis der Eugenie Die jüdische Reformpädagogin und Salonière Eugenie Schwarzwald wird am 6. Juni mit einem Buch im Jüdischen Museum Wien gewürdigt. Wien, 30.05.2018 Gibt es wirklich ein verschollenes oder ein nie gemaltes Gemälde von Oskar Kokoschka, das die Reformpädagogin und Salonière Eugenie Schwarzwald (1872‐1940) zeigt? Nicht nur diese Frage wird bei der „Testamentseröffnung“ im Jüdischen Museum Wien geklärt. Bei der Buchpräsentation wird diese Frage beantwortet wie auch die Geschichte und die Aktivitäten der altösterreichischen Reformpädagogin und Salonière Eugenie Schwarzwald beleuchtet. Hauptakteure dieses Abends sind die Sprecherin Bettina Rossbacher und der Historiker Robert Streibel, der die Feuilletons von Eugenie Schwarzwald im Löcker Verlag herausgebracht hat. Wer „die“ Schwarzwald kennenlernen will, muss ihre Artikel lesen und davon hat sie viele geschrieben, nicht nur in der „Neuen Freien Presse“. Ihre Feuilletons sind ihr Vermächtnis. Im Band „Das Vermächtnis der Eugenie“ sind 80 abgedruckt. Neun Feuilletons werden in einer gekürzten Version vorgestellt. Zu hören sind unter anderem: „Der Redner Kokoschka“, „Die Erziehung der modernen jungen Mädchen“, „Gottfried Keller und die junge Wienerin“, „Lehrer Schönberg“ und der programmatische Artikel „Schule von heute“. Eine Berühmtheit mit namhaften Freunden Eugenie Schwarzwald war eine Berühmtheit, davon zeugen nicht nur die zahlreichen Artikel und Hinweise in den Zeitungen, ihre Vortragsreisen und die Auftritte im Rundfunk bereits ab Mitte der 20er Jahre. In Musils „Mann ohne Eigenschaften“ taucht sie als Diotima auf. Aber auch Hugo Bettauer, Paul Stefan, Jakob Wassermann und Felix Dörmann haben ihr ein Denkmal gesetzt. In ihrem Salon waren der Pianist Rudolf Serkin, Peter Altenberg, Robert Musil, Oskar Kokoschka, Adolf Loos, Karl Kraus, Egon Friedell, Elias Canetti und auch Rainer Maria Rilke anzutreffen. -

Edict 13. Concerning the City of Alexandria and the Egyptian

Edict 13. Concerning the city of Alexandria and the Egyptian provinces. (De urbe Alexandrinorum et Aegyptiacis provinciis.) _________________________ The same emperor (Justinian) to Johannes, glorious Praetorian Prefect of the Orient. Preface. As we deem even the smallest things worthy of our care, much less do we leave matters that are important and uphold our republic without attention, or permit them to be neglected or in disorder, especially since we are served by Your Excellency who has at heart our welfare, and the increase of the public revenue, and the wellbeing of our subjects. Considering, therefore, that, though in the past the collection of public moneys seemed to be in fair order, in other places it was in such confusion in the diocese of Egypt that it was not even known here what was done in the province, we wondered that the status of this matter had hitherto been left disarranged; but God has permitted this also to be left (to be put in order) in our times and under your ministry. Though they (the officials) sent us grain from there, they would not contribute anything else; the taxpayers all unanimously affirmed that everything was collected from them in full, but the prefects of the country districts (pagarchae), the curials, the collectors of taxes (practores), and especially the officiating (augustal) prefects so managed the matter that no one could know anything about it and so that it was profitable to themselves alone. Since, therefore, we could never correct or properly arrange things, if the management were left in disorder, we have decided to curtail the administration of the man at the head of Eyptian affairs, namely that of the Augustal Prefect. -

DISCLOSURE TEMPLATE Gilead Sciences Gesmbh

PHARMIG CODE OF CONDUCT - GUIDANCE REGARDING ARTICLE 9 - STANDARDIZED DISCLOSURE TEMPLATE Gilead Sciences GesmbH DISCLOSURE TEMPLATE - ARTICLE 9 CoC (TRANSPARENCY) Reporting period (calendar year):2020 Date of publication:30/06/2021 Where available: Donations Contribution to costs of events Fees for services and Full Name Practice or business address physician and Grants (cf. Article 9.4a 1) (i), (ii) consultancy(cf. number to HCOs CoC and/or Article 9.4b 2) (i), Article 9.4a 2) CoC commercial (ii), (iii) CoC) and/or Article 9.4b register number, 3) CoC) association register number TOTAL Optional (cf. (cf. (cf. (cf. per(cf. HCP, Article all transfers 9.4 of (cf. Support Registrati HCPTravel will be summed& up]Fees Outlays Article Article Article Article CoC) Article agreements on fees accomodati 9.4 CoC) 9.4 CoC) 9.4 CoC) 9.4 CoC) 9.4b 1) with HCOs on CoC) / third parties appointed by HCOs to manage an event Priv.-Doz. Dr Kinderspitalgass Attarbaschi Wien, Alsergrund Austria N/A N/A 1,210 1,210 e 6 Andishe Dr. Bachmayer Oberndorf bei Paracelsusstraße Austria N/A N/A 330 330 H Sebastian Salzburg 37 C P s ao. Univ.Prof. Dr. Bellmann Innsbruck Austria Anichstraße 35 N/A N/A 800 800 Romuald Dr. Breitenecker Otto-Bauer-Gasse Wien, Mariahilf Austria N/A N/A 1,950 112 2,062 Florian 15/10 Where available: Donations Contribution to costs of events Fees for services and Full Name Practice or business address physician and Grants (cf. Article 9.4a 1) (i), (ii) consultancy(cf. -

The Marshall Plan in Austria 69

CAS XXV CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIANAUSTRIAN STUDIES STUDIES | VOLUME VOLUME 25 25 This volume celebrates the study of Austria in the twentieth century by historians, political scientists and social scientists produced in the previous twenty-four volumes of Contemporary Austrian Studies. One contributor from each of the previous volumes has been asked to update the state of scholarship in the field addressed in the respective volume. The title “Austrian Studies Today,” then, attempts to reflect the state of the art of historical and social science related Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.) • Austrian Studies Today studies of Austria over the past century, without claiming to be comprehensive. The volume thus covers many important themes of Austrian contemporary history and politics since the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1918—from World War I and its legacies, to the rise of authoritarian regimes in the 1930s and 1940s, to the reconstruction of republican Austria after World War II, the years of Grand Coalition governments and the Kreisky era, all the way to Austria joining the European Union in 1995 and its impact on Austria’s international status and domestic politics. EUROPE USA Austrian Studies Studies Today Today GünterGünter Bischof,Bischof, Ferdinand Ferdinand Karlhofer Karlhofer (Eds.) (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Studies Today Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 25 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2016 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.