How Water and Its Use Shaped the Spatial Development of Vienna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Dubai [Metro]Polis: Infrastructural Landscapes and Urban Utopia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5640/dubai-metro-polis-infrastructural-landscapes-and-urban-utopia-155640.webp)

Dubai [Metro]Polis: Infrastructural Landscapes and Urban Utopia

Dubai [Metro]polis: Infrastructural Landscapes and Urban Utopia When Dubai Metro was launched in 2009, it became a new catalyst for urban change but also a modern tool to interact with the city - providing a visual experience and an unprecedented perception of moving in space and time, almost at the edge between the imaginary and the real. By drawing on the traditional association between train, perception and the city we argue that the design and planning of Dubai Metro is intended as a signifier of modernity for the Gulf region, with its futuristic designs and in the context of the local socio-cultural associations. NADIA MOUNAJJED INTRODUCTION Abu Dhabi University For the last four decades, Dubai epitomized a model for post-oil Gulf cities and positioned itself as a subject for visionary thinking and urban experimentation. PAOLO CARATELLI During the years preceding 2008, Dubai became almost a site of utopia - evoking Abu Dhabi University a long tradition of prolific visionary thinking about the city – particularly 1970s utopian projects. Today skyscrapers, gated communities, man-made islands, iconic buildings and long extended waterfronts, dominate the cityscape. Until now, most of the projects are built organically within a fragmented urban order, often coexisting in isolation within a surrounding incoherence. When inaugu- rated in 2009, Dubai Metro marked the beginning of a new association between urbanity, mobility and modernity. It marked the start of a new era for urban mass transit in the Arabian Peninsula and is now perceived as an icon of the emirate’s modern urbanity (Ramos, 2010, Decker, 2009, Billing, n. -

Footpath Description

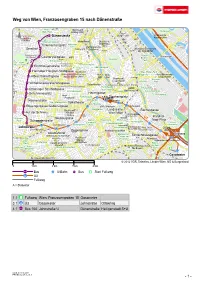

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

Notes of Michael J. Zeps, SJ

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 1-1-2011 Documents of Baudirektion Wien 1919-1941: Notes of Michael J. Zeps, S.J. Michael J. Zeps S.J. Marquette University, [email protected] Preface While doing research in Vienna for my dissertation on relations between Church and State in Austria between the wars I became intrigued by the outward appearance of the public housing projects put up by Red Vienna at the same time. They seemed to have a martial cast to them not at all restricted to the famous Karl-Marx-Hof so, against advice that I would find nothing, I decided to see what could be found in the archives of the Stadtbauamt to tie the architecture of the program to the civil war of 1934 when the structures became the principal focus of conflict. I found no direct tie anywhere in the documents but uncovered some circumstantial evidence that might be explored in the future. One reason for publishing these notes is to save researchers from the same dead end I ran into. This is not to say no evidence was ever present because there are many missing documents in the sequence which might turn up in the future—there is more than one complaint to be found about staff members taking documents and not returning them—and the socialists who controlled the records had an interest in denying any connection both before and after the civil war. Certain kinds of records are simply not there including assessments of personnel which are in the files of the Magistratsdirektion not accessible to the public and minutes of most meetings within the various Magistrats Abteilungen connected with the program. -

Investigation Future Planning of Railway Networks in the Arabs Gulf Countries

M. E. M. Najar & A. Khalfan Al Rahbi, Int. J. Transp. Dev. Integr., Vol. 1, No. 4 (2017) 654–665 INVESTIGATION FUTURE PLANNING OF RAILWAY NETWORKS IN THE ARABS GULF COUNTRIES MOHAMMAD EMAD MOTIEYAN NAJAR & ALIA KHALFAN AL RAHBI Department of Civil Engineering, Middle East College, Muscat, Oman ABSTRACT Trans-border railroad in the Arabian Peninsula dates back to the early 20th century in Saudi Arabia. Over the recent decades due to increasing population and developing industrial zones, the demands are growing up over time. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) is now embarking on one of the largest modern cross-border rail networks in the world. This is an ambitious step regarding the planning and establishment of the rail network connecting all the six GCC countries. This railway network will go through at least one city in each country to link the cities of Kuwait in Kuwait, Dammam in Saudi Arabia, Manama in Bahrain, Doha in Qatar, the cities of Abu Dhabi and Al Ain in the United Arab Emirates and Sohar and then Muscat in Oman in terms of cargo and passengers. The area of investigation covers different aspects of the shared Arabian countries rail routes called ‘GCC line’ and their national rail network. The aim of this article is to study the existing future plans and policies of the GCC countries shared line and domestic railway network. This article studies the national urban (light rail transportation (LRT), metro (subways) and intercity rail transportation to appraise the potential of passenger movement and commodity transportation at present and in the future. -

Transit Architecture for Growing Cities

COMMUNICATIVE DESIGN: TRANSIT ARCHITECTURE FOR GROWING CITIES A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Architecture by James Derek Holloway June 2014 © 2014 James Derek Holloway ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Communicative Design: Transit Architecture for Growing Cities AUTHOR: James Derek Holloway DATE SUBMITTED: June 2014 COMMITTEE CHAIR: Umut Toker, Ph.D. Associate Professor of City and Regional Planning COMMITTEE MEMBER: Mark Cabrinha, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Architecture COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kevin Dong, SE Professor of Architectural Engineering iii ABSTRACT Communicative Design: Transit Architecture for Growing Cities James Derek Holloway Increasing urban populations are currently magnifying the importance of the transit station in the context of its surrounding systems. In order to prepare our cities for higher population densities in the future, an examination of the relationships between station form and individual experience may lead to the identification of specific design objectives with implications for increased pub- lic transit riderships. Data is collected through research on sensory perception in architecture, spatial organization, and connectivity between an individual structure and it’s local surroundings. Site-specific observations and information describing current professional practices are used to determine prominent design objectives for future implementation. Keywords: -

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Erika Weinzierl Emeritus Professor of History University of Vienna Working Paper 01-1 October 2003 ©2003 by the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS). Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from CAS. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. CAS permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of CAS Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses; teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce CAS Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota, 314 Social Sciences Building, 267 19th Avenue S., Minneapolis MN 55455. Tel: 612-624-9811; fax: 612-626-9004; e-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction: The Rise of the Viennese Jewish Middle Class The rapid burgeoning and advancement of the Jewish middle class in Vienna commenced with the achievement of fully equal civil and legal rights in the Fundamental Laws of December 1867 and the inter-confessional Settlement (Ausgleich) of 1868. It was the victory of liberalism and the constitutional state, a victory which had immediate and phenomenal demographic and social consequences. In 1857, Vienna had a total population of 287,824, of which 6,217 (2.16 per cent) were Jews. -

VIENNA UNIVERSITY of TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Gusshausstrasse 28 / 1St Floor, A-1040 Wien

VIENNA UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL OFFICE Gusshausstrasse 28 / 1st floor, A-1040 Wien Contact: Tel: +43 (0)1 58801 - 41550 / 41552 Fax: +43 (0)1 58801 - 41599 Email: [email protected] ANKUNFT http://www.tuwien.ac.at/international Opening hours: Monday, Thursday: 9:30 a.m. – 11:30 a.m., 1:30 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. Wednesday: 9:30 a.m. – 11:30 a.m. How to reach us: Metro: U1 (Station Taubstummengasse) U2 (Station Karlsplatz) U4 (Station Karlsplatz) Tram: Line 62 (Station Paulanergasse) Line 65 (Station Paulanergasse) Line 71 (Station Schwarzenbergplatz) Welcome Guide TU Wien │ 1 Published by: International Office of Vienna University of Technology Gusshausstrasse 28 A-1040 Wien © 2014 Print financed by funds of the European Union 2 │ Welcome Guide TU Wien CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT TU WIEN .............................................. 5 1 History of Vienna University of Technology ......................................... 5 2 Structure of Vienna University of Technology ...................................... 6 3 Fields of Study ..................................................................................... 7 4 The Austrian National Union of Students ........................................... 11 PLANNING IN YOUR HOME COUNTRY..................................................... 13 1 Applying for Studies at TU Wien ........................................................ 13 2 Visa ....................................................................................................13 3 Linguistic Requirements .................................................................... -

(RAKO) Donaukanal

Radkombitransport (RAKO) Donaukanal Konzept für eine moderne City Logistik per Wasser und Rad INHALTLICHER ENDBERICHT Verfasser/innen: Mag. Reinhard Jellinek, DI Willy Raimund, Mag. Judith Schübl, DI Christine Zopf-Renner (Österreichische Energieagentur) DI Karl Reiter, Dr. Susanne Wrighton (FGM-AMOR) DI Richard Anzböck Zivilingenieur für Schiffstechnik Florian Weber, Heavy Pedals Lastenradtransport und -verkauf OG Fördergeber: Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Innovation und Technologie Datum: Wien, Februar 2016 IMPRESSUM Herausgeberin: Österreichische Energieagentur – Austrian Energy Agency, Mariahilfer Straße 136, A-1150 Wien, T. +43 (1) 586 15 24, Fax DW - 340, [email protected] | www.energyagency.at Für den Inhalt verantwortlich: DI Peter Traupmann | Gesamtleitung: Mag. Reinhard Jellinek | Lektorat: Mag. Michaela Ponweiser | Layout: Mag. Reinhard Jellinek | Gefördert im Programm „Mobilität der Zukunft“ vom Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Innovation und Technologie (bmvit) Herstellerin: Österreichische Energieagentur – Austrian Energy Agency | Verlagsort und Herstellungsort: Wien Nachdruck nur auszugsweise und mit genauer Quellenangabe gestattet. Gedruckt auf chlorfrei gebleichtem Papier. Die Österreichische Energieagentur hat die Inhalte der vorliegenden Publikation mit größter Sorgfalt recherchiert und dokumentiert. Für die Richtigkeit, Vollständigkeit und Aktualität der Inhalte können wir jedoch keine Gewähr übernehmen. Kurzfassung „Radkombitransport (RAKO) Donaukanal“ ist ein Forschungsprojekt, das vom Forschungsprogramm „Mobilität -

Dubai Real Estate Sector

Sector Monitor Series Dubai Real Estate Sector Dr. Eisa Abdelgalil Bader Aldeen Bakheet Data Management and Business Research Department 2007 Published by: DCCI – Data Management & Business Research Department P.O. Box 1457 Tel: + 971 4 2028410 Fax: + 971 4 2028478 Email: dm&[email protected] Website: www.dcci.ae Dubai, United Arab Emirates All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval or computer system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, taping or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN ………………………… i Table of Contents Table of Contents...........................................................................................................ii iii ....................................................................................................................ﻣﻠﺨﺺ ﺗﻨﻔﻴﺬي Executive Summary......................................................................................................vi 1. Introduction................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background..........................................................................................................1 1.2 Objective..............................................................................................................1 1.3 Research questions...............................................................................................1 1.4 Methodology and data..........................................................................................2 -

Jewish Communities of Leopoldstadt and Alsergrund

THE VIENNA PROJECT: JEWISH COMMUNITIES OF LEOPOLDSTADT AND ALSERGRUND Site 1A: Introduction to Jewish Life in Leopoldstadt Leopoldstadt, 1020 The history of Jews in Austria is one of repeated exile (der Vertreibene) and return. In 1624, after years and years of being forbidden from living in Vienna, Emperor Ferdinand III decided that Jewish people could return to Vienna but would only be allowed to live in one area outside of central Vienna. That area was called “Unterer Werd” and later became the district of Leopoldstadt. In 1783, Joseph II’s “Toleranzpatent” eased a lot of the restrictions that kept Jews from holding certain jobs or owning homes in areas outside of Leopoldstadt. As a result, life in Vienna became much more open and pleasant for Jewish people, and many more Jewish immigrants began moving to Vienna. Leopoldstadt remained the cultural center of Jewish life, and was nicknamed “Mazzeinsel” after the traditional Jewish matzo bread. Jews made up 40% of the people living in the 2nd district, and about 29% of the city’s Jewish population lived there. A lot of Jewish businesses were located in Leopoldstadt, as well as many of the city’s synagogues and temples. Tens of thousands of Galician Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe made their home there, and brought many of their traditions (such as Yiddish literature) with them. Questions to Consider Look up the history of Jewish eXile and return in Vienna. How many times were they sent away from the city, and why did the city let them return? What were some of the restrictions on Jewish life in Vienna before the “Toleranzpatent” in 1783? What further rights did Jewish people gain in 1860? How did this affect Jewish life and culture in Vienna in the late 1800s and early 1900s? Describe the culture of Leopoldstadt before 1938. -

Red Line of Dubai's Mass Transit System

Red Line Of dubai’s mass courtesyImage of Gulf News tRansit system In February 2006 groundworks screen doors (PSD), which will improve resistant to dynamic loads than other commenced on the Red Line of Dubai’s the safety and comfort of users, and fixing methods. mass transit system. increase the operational efficiency of the The PSD system was tested through one metro system. million cycles to verify reliability and Later that year, a consortium lead by performance. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, including HALFEN HTA 52/34 cast-in channel Kajima Corporation and Obayshi is being used by Mitsubishi Heavy The Dubai Metro project is the first Corporation began work on Phase II, the Industries to fix the platform screen mass transit rail system for the Gulf Green Line. doors in place. region, and HALFEN is proud to be a The channel provides an adjustable part of such an international project, Of the 47 stations on these lines, fixing point, which can compensate for and the development of the Gulf’s some are being fitting with platform construction tolerances, and is also more infrastructure. • Year of construction: 2006 • Client: Dubai Roads and Transport Authority • Contractor: Mitsubishi Heavy Industries • Specification: HTA 52/34 350 mm hot dip galvanized channel HALFEN channel installed in platform slab to secure PSD base. The channel allows for construction tolerance as well as adjustment of the final installation position, and allows the PSD system to be rapidly fixed towards the end of the construction program, without affecting any finishes or requiring any touch-up. Used worldwide for over 80 years as a fixing to concrete or steel, HALFEN channel is used extensively in the rail and infrastructure sectors where connection reliability is critical. -

Simmering: Platz Zum Wohnen Und Für Die Wirtschaft

Nr. 27/28 · 8. 7. 2016 Nr. 27/28 · 8. 7. 2016 8 · Wien · Wiener Wirtschaft Wiener Wirtschaft · Wien · 9 BEZAHLTE ANZEIGE Simmering: Platz zum Wohnen und für die Wirtschaft Simmering zählte in den letzten Jahren zu den am Dagegen ist das Areal Ailecgas- Simmering auch architektonisch stärksten wachsenden Wiener Bezirken. Der Stadtteil se (84 Hektar) im Südosten des einiges zu bieten. ist aber auch ein wichtiger Wirtschaftsbezirk, der Bezirks noch dünn besiedelt. Vor „Lebensader” des Bezirks ist die allem für nicht mischfähige Be- 6,5 Kilometer lange Simmerin- noch Platz für neue Betriebe bietet. triebe, also solche, die nicht prob- ger Hauptstraße, auf den ersten lemlos neben anderen Nutzungen zwei Kilometern auch die größte Arbeiterbezirk und Heimat des jekte von Genossenschaften und angesiedelt werden können, ist das Einkaufsstraße. Wichtige Bezirks- Zentralfriedhofs - wer meint, dass Bauträgern. Die aktuelle Wohn- Gebiet eine wichtige Flächenre- versorger sind auch der heuer neu Wiens elfter Bezirk Simmering bauoffensive der Stadt Wien geht serve. Allerdings ist es verkehrs- eröffnete Einkaufspark huma ele- durch diese Attribute hinreichend allerdings am Bezirk etwas vorbei. technisch kaum erschlossen, es ven in der Landwehrstraße, der im beschrieben sei, der irrt. Zwischen Sie sieht in den nächsten zwei fehlt sowohl die Anbindung an Endausbau 50.000 Quadratmeter der Südosttangenten-Querung am Jahren dort lediglich ein Neubau- den öffentlichen Verkehr als auch Verkaufsfläche bieten soll, und das Namen „Punkt11” verteilt der n Kurz Notiert Einkaufsstraße Simmeringer Hauptstraße oberen Ende und der Stadtgrenze projekt mit 150 Wohnungen in der ans hochrangige Straßennetz. Die in die Simmeringer Hauptstraße Verein mehrmals jährlich eine zu Schwechat im Süden bietet Eisteichgasse vor.