Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

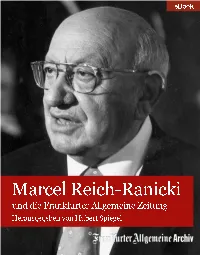

Marcel Reich-Ranicki

eBook Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel F.A.Z.-eBook 21 Frankfurter Allgemeine Archiv Projektleitung: Franz-Josef Gasterich Produktionssteuerung: Christine Pfeiffer-Piechotta Redaktion und Gestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher eBook-Produktion: rombach digitale manufaktur, Freiburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Rechteerwerb: [email protected] © 2013 F.A.Z. GmbH, Frankfurt am Main. Titelgestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher. Foto: F.A.Z.-Foto / Barbara Klemm ISBN: 978-3-89843-232-0 Inhalt Ein sehr großer Mann 7 Marcel Reich-Ranicki ist tot – Von Frank Schirrmacher ..... 8 Ein Leben – Von Claudius Seidl .................... 16 Trauerfeier für Reich-Ranicki – Von Hubert Spiegel ...... 20 Persönlichkeitsbildung 25 Ein Tag in meinem Leben – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 26 Wie ein kleiner Setzer in Polen über Adolf Hitler trium- phierte – Das Gespräch führten Stefan Aust und Frank Schirrmacher ................................. 38 Rede über das eigene Land – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki ... 55 Marcel Reich-Ranicki – Stellungnahme zu Vorwürfen ..... 82 »Mein Leben«: Das Buch und der Film 85 Die Quellen seiner Leidenschaft – Von Frank Schirrmacher � 86 Es gibt keinen Tag, an dem ich nicht ans Getto denke – Das Gespräch führten Michael Hanfeld und Felicitas von Lovenberg ................................... 95 Stille Hoffnung, nackte Angst: Marcel-Reich-Ranicki und die Gruppe 47 107 Alles war von Hass und Gunst verwirrt – Von Hubert Spiegel 108 Und alle, ausnahmslos alle respektierten diesen Mann – Von Marcel-Reich-Ranicki ....................... 112 Das Ende der Gruppe 47 – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 116 Große Projekte: die Frankfurter Anthologie und der »Kanon« 125 Der Kanonist – Das Gespräch führte Hubert Spiegel .... -

June 2019 the Edelweiss Am Rio Grande Nachrichten

Edelweiss am Rio Grande German American Club Newsletter-June 2019 1 The Edelweiss am Rio Grande Nachrichten The newsletter of the Edelweiss am Rio Grande German American Club 4821 Menaul Blvd., NE Albuquerque, NM 87110-3037 (505) 888-4833 Website: edelweissgac.org/ Email: [email protected] Facebook: Edelweiss German-American Club June 2019 Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kaffeeklatsch Irish Dance 7pm Karaoke 3:00 pm 5-7 See page 2 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 DCC Mtng & Irish Dance 7pm Strawberry Fest Dance 2-6 pm Essen und Dance See Pg 4 Sprechen pg 3 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Jazz Sunday GAC Board Irish Dance 7pm Karaoke Private Party 2:00-5:30 pm of Directors 5-7 6-12 6:30 pm 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 Irish Dance 7pm Sock Hop Dance See Pg 4 30 2pm-German- Language Movie- see pg 3 Edelweiss am Rio Grande German American Club Newsletter-June 2019 2 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Summer is finally here and I’m looking forward to our Anniversary Ball, Luau, Blues Night and just rolling out those lazy, hazy, crazy days of Summer. On a more serious note there have been some misunderstandings between the GAC and one of our oldest and most highly valued associate clubs the Irish-American Society (IAS). Their President, Ellen Dowling, has requested, and I have extended an invitation to her, her Board of Directors, and IAS members at large to address the GAC at our next Board meeting. -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-14571-8 - German Intellectuals and the Nazi Past A. Dirk Moses Excerpt More information Introduction The proposition that the Federal Republic of Germany has developed a healthy democratic culture centered around memory of the Holocaust has almost become a platitude.1 Symbolizing the relationship between the Federal Repub- lic’s liberal political culture and honest reckoning with the past, an enormous Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe adjacent to the Bundestag (Federal Parliament) and Brandenburg Gate in the national capital was unveiled in 2005. States usually erect monuments to their fallen soldiers, after all, not to the vic- tims of these soldiers. In the eyes of many, the West German and, since 1990, the united German experience has become the model of how post-totalitarian and postgenocidal societies “come to terms with the past.”2 Germany now seemed no different from the rest of Europe – or, indeed, from the West generally. Jews from Eastern Europe are as happy to settle there as they are to emigrate to Israel, the United States, or Australia.3 1 Bill Niven, Facing the Nazi Past: United Germany and the Legacy of the Third Reich (London and New York, 2002). For an excellent overview of postwar memory politics, see Andrew H. Beattie, “The Past in the Politics of Divided and Unified Germany,” in Max Paul Friedman and Padraic Kenney, eds., Partisan Histories: The Past in Contemporary Global Politics (Houndmills, 2005), 17–38. 2 For example, Daniel J. Goldhagen, “Modell Bundesrepublik: National History, Democracy and Internationalization in Germany,” Common Knowledge, 3 (1997), 10–18. -

Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

STUNDE NULL: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Occasional Paper No. 20 Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE WASHINGTON, D.C. STUNDE NULL The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago Edited by Geoffrey J. Giles Occasional Paper No. 20 Series editors: Detlef Junker Petra Marquardt-Bigman Janine S. Micunek © 1997. All rights reserved. GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE 1607 New Hampshire Ave., NW Washington, DC 20009 Tel. (202) 387–3355 Contents Introduction 5 Geoffrey J. Giles 1945 and the Continuities of German History: 9 Reflections on Memory, Historiography, and Politics Konrad H. Jarausch Stunde Null in German Politics? 25 Confessional Culture, Realpolitik, and the Organization of Christian Democracy Maria D. Mitchell American Sociology and German 39 Re-education after World War II Uta Gerhardt German Literature, Year Zero: 59 Writers and Politics, 1945–1953 Stephen Brockmann Stunde Null der Frauen? 75 Renegotiating Women‘s Place in Postwar Germany Maria Höhn The New City: German Urban 89 Planning and the Zero Hour Jeffry M. Diefendorf Stunde Null at the Ground Level: 105 1945 as a Social and Political Ausgangspunkt in Three Cities in the U.S. Zone of Occupation Rebecca Boehling Introduction Half a century after the collapse of National Socialism, many historians are now taking stock of the difficult transition that faced Germans in 1945. The Friends of the German Historical Institute in Washington chose that momentous year as the focus of their 1995 annual symposium, assembling a number of scholars to discuss the topic "Stunde Null: The End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their contributions are presented in this booklet. -

Fashion Germany

FASHION GERMANY MARTINA RINK FASHION GERMANY PRESTEL/ MUNICH . LONDON . NEW YORK Introduction · Martina Rink 8 Tomas Maier 12 Marko Matysik 14 Yasmin Heinz 18 Felix Lammers 20 Torsten Neeland 22 Angelica Blechschmidt 24 Susanne Tide-Frater 26 Jasmin Khezri 28 Josef Voelk and Emmanuel de Bayser 30 Olaf Hajek 32 Dirk Schönberger 34 Vanessa von Bismarck 35 Julia von Boehm 36 Kai Margrander 40 Jina Khayyer 42 Mumi Haiati 43 Kristian Schuller 44 Donald Schneider 48 Deycke Heidorn 52 Anna Bauer 54 Alex Wiederin 56 Silke Werzinger 60 Leyla Piedayesh 62 Jen Gilpin 64 Magomed Dovjenko 68 Julia Freitag 69 Schohaja 70 Rike Döpp 74 Thomas BenTz AND Oliver Lühr 75 Christoph Amend 76 Mirko Borsche 78 Boris Bidjan Saberi 82 Damir Doma 82 CONTENTS Michael Sontag 83 Vladimir Karaleev 83 Raoul Keil 84 Saskia Diez 86 René Storck 87 Armin Morbach 88 Toni Garrn 92 Heidi Klum/Thomas Hayo 93 Annette and Daniela Felder 94 Alexandra von Rehlingen and Andrea Schoeller 96 Stefan Eckert 97 Susanne Oberbeck 98 Constantin Bjerke 100 Sascha Breuer 102 Philipp Plein 104 Andreas Ortner 106 Bettina Harst 108 Wolfgang Joop 110 Kera Till 112 Papis Loveday 113 Claudia Skoda 114 Alexandra Fischer-Roehler and Johanna Kühl 116 Esma Annemon Dil 118 Didi Ilse 119 Sandra Bauknecht 120 Alexx and Anton 122 Marcus Kurz 126 Burak Uyan 128 Corinna Springer 130 Kai Kühne 131 Marie Schuller 132 Vincent Peters 134 Andrea Karg 136 Louisa von Minckwitz 138 André Borchers 139 Petra van Bremen 140 Johnny Talbot and Adrian Runhof 142 Marco Stein 143 Johannes Huebl 144 Annelie Augustin and Odély Teboul 146 Petra Bohne 148 Nini Gollong 149 Tatjana Patitz 150 Natalie Acatrini 151 Gladys Perint Palmer 152 Klaus Stockhausen 153 Dawid Tomaszewski 154 Dorothee Schumacher 156 Feride Uslu 158 Bernhard Willhelm 160 Tillmann Lauterbach 162 Karl Anton Koenigs 164 Diane Kruger 166 Sascha Lilic 167 Esther Haase 168 Veruschka 169 F. -

Volksbühne Am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz 1992-2017

Volksbühne am Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz 1992-2017 Ein Film von Andreas Deinert, Moritz Denis, Matthias Ehlert, Wolfgang Gaube, Rosa Grünberg, Eike Hosenfeld, Michael Kaczmarek, Thomas Kleinwächter, Lutz Pehnert Caroline Peters, Susann Schimk, Johannes Schneeweiß, Jens Stubenrauch, Christoph Sturm, Jörg Theil, Mieke Ulfig, Adama Ulrich Mit Kathrin Angerer, Henry Hübchen, Susanne Düllmann, Karin Ugowski, Katrin Knappe, Alexander Scheer, Martin Wuttke, Frank Castorf, Herbert Fritsch, Sophie Rois, Marc Hosemann Lilith Stangenberg, Wolfram Koch, Elisabeth Zumpe, Ingo Günther, Herbert Sand, Wilfried Ortmann, Walfriede Schmitt, Heide Kipp, Annett Kruschke, Ulrich Voß, Harald Warmbrunn Winfried Wagner, Magne Hovard Brekke, Jon-Kaare Koppe, Peter-René Lüdicke, Bruno Cathomas, Kurt Naumann, Gerd Preusche, Torsten Ranft, Joachim Tomaschewsky, Jürgen Rothert Klaus Mertens, Bodo Krämer, Sabine Svoboda, Harry Merkel, Christiane Schober, Claudia Michelsen, Meral Yüzgülec, Astrid Meyerfeldt, Annekathrin Bürger, Dietmar Huhn, Hans-Uwe Bauer Andreas Speichert, Frank Meißner, Susanne Strätz, Robert Hunger-Bühler, Lajos Talamonti, Steve Binetti, Christoph Schlingensief, Wilfried Rott, Adriana Almeida, Walter Bickmann Christian Camus, Jean Chaize, Amy Coleman, Christina Comtesse, Beatrice Cordua, Ana Veronica Coutinho, Brigitte Cuvelier, Gernot Frischling, Andrea Hovenbitzer, Susana Ibañez Martin Kasper, Kristine Keil, Monica Kodato, Martin Lämmerhirt, Ireneu Marcovecchio, Mauricio Oliveira, Mauricio Ribeiro, Liliana Saldaña, Aliksey Schoettle, Christian Schwaan -

Berg Literature Festival Committee) Alexandra Eberhard Project Coordinator/Point Person Prof

HEIDELBERG UNESCO CITY OF LITERATURE English HEIDEL BERG CITY OF LITERATURE “… and as Carola brought him to the car she surprised him with a passionate kiss before hugging him, then leaning on him and saying: ‘You know how really, really fond I am of you, and I know that you are a great guy, but you do have one little fault: you travel too often to Heidelberg.’” Heinrich Böll Du fährst zu oft nach Heidelberg in Werke. Kölner Ausgabe, vol. 20, 1977–1979, ed. Ralf Schell and Jochen Schubert et. al., Kiepenheuer & Witsch Verlag, Cologne, 2009 “One thinks Heidelberg by day—with its surroundings—is the last possibility of the beautiful; but when he sees Heidelberg by night, a fallen Milky Way, with that glittering railway constellation pinned to the border, he requires time to consider upon the verdict.” Mark Twain A Tramp Abroad Following the Equator, Other Travels, Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, 2010 “The banks of the Neckar with its chiseled elevations became for us the brightest stretch of land there is, and for quite some time we couldn’t imagine anything else.” Zsuzsa Bánk Die hellen Tage S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 2011 HEIDEL BERG CITY OF LITERATURE FIG. 01 (pp. 1, 3) Heidelberg City of Literature FIG. 02 Books from Heidelberg pp. 4–15 HEIDELBERG CITY OF LITERATURE A A HEIDELBERG CITY OF LITERATURE The City of Magical Thinking An essay by Jagoda Marinic´ 5 I think I came to Heidelberg in order to become a writer. I can only assume so, in retro spect, because when I arrived I hadn’t a clue that this was what I wanted to be. -

Vergangenheitsbewältigung and the Danzig Trilogy

vergangenheitsbewältigung and the danzig trilogy Joseph Schaeffer With the end of the Second World War in 1945, Germany was forced to examine and come to terms with its National Socialist era. It was a particularly difficult task. Many Germans, even those who had suspected the National Socialist crimes, were shocked by the true barbarity of the Nazi regime. Günter Grass, who spent 1945 in an American POW camp listening to the Nurem- berg Trials, was one of those Germans. How could the Holocaust have arisen from the land of poets and philosophers? German authors began to seek the answer to this question immediately following the end of WWII, and this pursuit naturally led to several different genres of German post-war literature. Some authors adopted the style of Kahlschlag (clear cutting), in which precise use of language would free German from the propaganda-laden connotations of Goebbel’s National Socialist Germany. Others spoke of a Stunde Null (Zero Hour), a new beginning without reflec- tion upon the past. These styles are easily recognizable in the works of early post-war authors like Alfred Andersch, Günter Eich, and Wolfgang Borchert. However, it would take ten years before German authors adopted the style of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, an analysis and overcom- ing of Germany’s past.1 In 1961 Walter Jens wrote that only works written after 1952 should be considered part of the genre of German post-war literature (cited in Cunliffe 3). Without a distanced analysis of the Second World War an author would be unable to produce a true work of art. -

Apolda European Design Award 2020

10. APOLDA EUROPEAN DESIGN AWARD 2020 APOLDA EUROPEAN DESIGN AWARD 2020 INHALT EDITORIAL ...................................................................................................................... 3 GENIE Dienstleister ZUKUNFtsgestalter .............................................................. 4 Apolda AKTUELL Apolda IN BERLIN ......................................................................................................... 8 STIMMEN ZUM WORKSHOP .......................................................................................... 10 Designerin IN ResidenCE II ..................................................................................... 12 Apolda 1993–2020 DAISY SCHreibt DEMNÄCHst EIN BUCH … ............................................................... 17 Apolda 10. AEDA 2020 DIE JURY ....................................................................................................................... 28 DER WETTBEWERB ....................................................................................................... 32 DIE PREISTRÄGER ........................................................................................................ 33 DIE WEITEREN EINGEREICHTEN ARBEITEN ................................................................. 42 Apolda DESIGNER NETWORK FASHION MOVES .......................................................................................................... 95 DIE SPONSOREN ......................................................................................................... -

GEFÄHRLICH, ABER GUT Die Lange Nacht Mit Dieter Hildebrandt Und

GEFÄHRLICH, ABER GUT Die Lange Nacht mit Dieter Hildebrandt und Volker Kühn Autor: Oliver Kranz Regie: Rita Höhne Redaktion: Monika Künzel Sendedatum: Deutschlandradio am 2.11.2013, 0.05-3.00 Uhr Deutschlandfunk am 2./3.11.2013, 23.05-2.00 Uhr Die Lange Nacht mit Dieter Hildebrandt und Volker Kühn Opener / 1.Stunde Titelmusik des Films "Kir Royal" 10 sec frei stehend, dann leise geblendet Volker Kühn: Wir wollten eine andere Republik. Wir wollten alles verändern, uns auch ein bisschen, aber doch mehr die anderen. Hildebrandt: "Es wird in Zukunft in unserer Republik keine Polizei mehr geben, weil bei uns dann keiner mehr kriminell sein muss. Es wird keiner mehr stehlen müssen. Es wird keiner mehr einen anderen betrügen müssen. In unserer Republik ist das nicht nötig, also brauchen wir keine Polizei." Adenauer: Wir haben einen Abgrund von Landesverrat im Lande. Volker Kühn: Dann hat heftig die Bild-Zeitung und Springer mitgeholfen, dass das Kabarett sich etablieren konnte, weil die ja das erst mal mit Schweigen übergangen haben, und dann haben sie gesagt: "ganz gefährlich. Reichskabarett/"Der Guerilla lässt grüßen": Also dann: Vorwärts mit der Berliner Parole "Lieber tot als rot!" Genauer: "Lieber Tote, als Rote." Volker Kühn: Und dann gab es ein Programm "Der Guerilla lässt grüßen", wo die dann geschrieben haben: "sehr gefährlich, aber leider sehr gut." Titelmusik des Films "Kir Royal", kurz hoch, dann Schlussakkord Oliver Kranz Wie haben Sie beide sich eigentlich kennen gelernt? Dieter Hildebrandt Ich weiß nicht, wer wen kennengelernt hat, aber ich glaube, er hat mich kennen gelernt, ich weniger ihn.