Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.T65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of Bolton As an Important Engineering and Textile Town in Early 1800 England

I. međunarodna konferencija u povodu 150. obljetnice tvornice torpeda u Rijeci i očuvanja riječke industrijske baštine 57 THE RISE OF BOLTON AS AN IMPORTANT ENGINEERING AND TEXTILE TOWN IN EARLY 1800 ENGLAND Denis O’Connor, Industrial Historian Bolton Lancashire, Great Britain INTRODUCTION The aim of this paper is to demonstrate that Great Britain changed, in the 19th Century, from a rural economy to one based on coal and iron. In doing so it created conditions for British civil, textile and mechanical engineers, such as Robert Whitehead of Bolton, to rise to positions of eminence in their particular fields. Such men travelled across Europe, and laid, through the steam engine and railways, the foundations for many of the regions present day industries. EARLY TEXTILES AND BLEACHING. RISE OF LOCAI INDUSTRIES The origins of Bolton’s textile and engineering industry lie back in the 12th Century with the appointment of a Crown Quality Controller called an Ulnager. During the reign of Henry V111 an itinerant historian Leland observed that ‘Bolton - upon - Moore Market standeth by the cotton and coarse yarns - Diverse villages above Bolton do make Cotton’ and that ‘They burne at Bolton some canelle (coal) of which the Pitts be not far off’. Coal, combined with the many powerful streams of water from the moorlands, provided the basic elements for the textile industry to grow, the damp atmosphere conducive to good spinning of thread. In 1772 a Directory of Manchester (10-12 miles distant) was published, in this can be seen the extent of cloth making in an area of about 12 miles radius round Manchester, with 77 fustian makers (Flax warp and cotton or wool weft) attending the markets, 23 of whom were resident in Bolton. -

Our Clarkson Family in England

Our Clarkson Family in England Blanche Aubin Clarkson Hutchison Text originally written in 1994 Updated and prepared for the “Those Clarksons” website in August 2008 by Aubin Hutchison and Pam Garrett Copyright Blanche Aubin Clarkson Hutchison 2008 In any work, copyright implicitly devolves to the author of that work. Copyright arises automatically when a work is first fixed in a tangible medium such as a book or manuscript or in an electronic medium such as a computer file. Table of Contents Title Page Table of Contents Introduction 1 Finding James in America 3 James Before the American Revolution 7 Blackley Parish, Lancashire 11 A Humorous Tale 17 Stepping Back from Blackley to Garstang 19 Garstang Parish, Lancashire 23 Plans for Further Searching 31 Appendix A: Reynolds Paper 33 Appendix B: Sullivan Journal 39 Appendix C: Weaving 52 Appendix D: Blackley Parish Register 56 Our Clarkson Family in England - 1 Chapter 1: Introduction My father, Albert Luther Clarkson, and his younger brother Samuel Edwin Clarkson Jr. were the most thoughtful and courteous gentlemen I ever knew. Somewhere in their heritage and upbringing these characteristics were dominant. How I wish they were still alive to enjoy with us the new bits of family history we are finding, for clues they passed along have led to many fascinating discoveries. These two brothers, Ab and Ed as they were called, only children of SE (Ed) and Aubin Fry Clarkson, actually knew a bit more about some of their mother’s family lines. This has led to exciting finds on Fry, Anderson, Bolling, Markham, Cole, Rolfe, Fleming, Champe, Slaughter, Walker, Micou, Hutchins, Brooks, Winthrop, Pintard, and even our honored bloodline to the Princess Pocahontas and her powerful father Powhatan! These families were early in Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and Virginia. -

Samuel Crompton (3 Dec 1753 - 26 Jun 1827)

Samuel Crompton (3 Dec 1753 - 26 Jun 1827) British inventor who contributed to the Industrial Revolution with his invention of the “spinning mule” to produce continuous, strong, fine yarn. (source) Samuel Crompton Crompton was born at Firwood Fold, near Bolton, England. He was 15 when he started working on a spinning jenny in the Hall'i'th'Wood1 mill, Bolton. The yarn then in use was soft, and broke frequently. He realized that an improved machine was needed. By 1774, at age 21, he began working on that project in his spare time, and continued for five years. He later wrote2 that he was in a “continual endeavour to realise a more perfect principle of spinning; and though often baffled, I as often renewed the attempt, and at length succeeded to my utmost desire, at the expense of every shilling I had in the world.” During this time, he supplemented his income from weaving, when the Bolton theatre was open, by earning eighteen pence a night as a violinist in the orchestra. Samuel Crompton (source) Drawing of the Spinning Mule Because of the machine-wrecking Luddites active during the Industrial Revolution, he worked as best he (1823) (source) could in secret while developing the machine. At one point, he kept it hidden in the roof of his house. (Luddites were handloom workers who violently rejected the changes produced by the Industrial Revolution, and destroyed mechanised looms, in their attempt to protect their livelihoods during harsh economic conditions.) In 1779, his invention was finished - the spinning mule. It was able to spin a continuous, strong, fine yarn by combining ideas from the spinning jenny of Richard Arkwright and the water frame of James Hargreaves. -

Education Teacher’S Kit

Industrial Heritage - The Textile Industry Education Teacher’s Kit Background There is archaeological evidence of textile production in Britain from the late-prehistoric period onwards. For many thousands of years wool was the staple textile product of Britain. The dominance of wool in the British textile industry changed rapidly during the eighteenth century with the development of mechanised silk production and then mechanised cotton production. By the mid-nineteenth century all four major branches of the textile industry (cotton, wool, flax, hemp and jute and silk) had been mechanised and the British landscape was dominated by over 10,000 mill buildings with their distinctive chimneys. Overseas competition led to a decline in the textile industry in the mid-twentieth century. Today woollen production is once again the dominant part of the sector together with artificial and man-made fibres, although output is much reduced from historic levels. Innovation Thomas Lombe’s silk mill, built in 1721, is regarded as the first factory-based textile mill in Britain. However, it was not until the handloom was developed following the introduction of John Kay’s flying shuttle in 1733 that other branches of the textile industry (notably cotton and wool) became increasingly mechanised. In the second half of the eighteenth century, a succession of major innovations including James Hargreaves’s spinning jenny (1764), Richard Arkwright’s water frame (1769), his carding engine (1775), and Samuel Crompton’s mule (1779), revolutionised the preparation and spinning of cotton and wool and led to the establishment of textile factories where several machines were housed under one roof. -

RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 100 the Derwent Valley 100 95 95

DERWENT VALLEY MILLS DERWENT VALLEY 100 The Derwent Valley 100 95 95 75 The Valley that changed the World 75 25 DERWENT VALLEY MILLS WORLD HERITAGE SITE 25 5 RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 5 0 0 Edited by David Knight Inscriptions on UNESCO's SITE RESEARCH FRAMEWORK WORLD HERITAGE prestigious World Heritage List are based on detailed research into the sites' evolution and histories. The role of research does not end with the presentation of the nomination or indeed the inscription itself, which is rst and foremost a starting point. UNESCO believes that continuing research is also central to the preservation and interpretation of all such sites. I therefore wholeheartedly welcome the publication of this document, which will act as a springboard for future investigation. Dr Mechtild Rössler, Director of the UNESCO Division for Heritage and the UNESCO World Heritage Centre 100 100 95 95 75 75 ONIO MU IM N R D T IA A L P W L O A I 25 R 25 D L D N H O E M R E I T I N A O GE IM 5 PATR 5 United Nations Derwent Valley Mills Educational, Scientific and inscribed on the World 0 Cultural Organisation Heritage List in 2001 0 Designed and produced by Derbyshire County Council, County Hall, Matlock Derbyshire DE4 3AG Research Framework cover spread print 17 August 2016 14:18:36 100 100 95 95 DERWENT VALLEY MILLS WORLD HERITAGE SITE 75 75 RESEARCH FRAMEWORK 25 25 5 Edited by David Knight 5 0 0 Watercolour of Cromford, looking upstream from the bridge across the River Derwent, painted by William Day in 1789. -

Bolton Museum

GB 0416 Pattern books Bolton Museum This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 29093 The National Archives List of Textile samples of woven, printed, dyed etc. fabric in the collections of Bolton Museum (Jan. 1977) R.J.B. Description Date Accession no. / 1 Peel Pattern Book - A pattern book of the calico-print circa trade. 36 leaves of notes and pattern samples and 1807-1821 D.1.1971. loosely inserted leaves. Belonged to Robert Peel, fath er of Sir Robert Peel, from print works of Church and Bury. 1 Pattern Book of printed and woven textile designs from 1841-46 D.3.1969. James Hardcastle & Co. ^Bradshaw Works. 1 Pattern Book of printed textile designs from James 1836-44 D. 2.1969 Hardcastle & Co., Bradshaw Works. 9 coloured Patterns on paper of various sizes, illust- A. 3.1967 rating different patterns U3ed in dyeing & printing cotton. 1 Book recording prices and samples referring to dyeing 1824-1827 A. 1.1967 and printing of cotton. Samples of printed and dyed cloth stuck in the book. 1 Book recording instructions and reports on various 1809 A.2.1967 dyeing processes for cotton, using different substances and how to obtain specific colours. Samples of printed and dyed textiles stuck in the book. Book inscribed *John Mellor Jnr. 1809". 1 Sample Book containing 19 small pieces of muslins made 1837 48-29 1/14 by John Bradshaw, Manufacturer, about 1837- John Bradshaw had previously been employed as manager of hand-loom weavers and in 1840 was appointed Relieving Officer for the Western District of Great Bolton. -

Textile Industry and the Factory System

What might be the advantages of factory weaving WhatWhatWhat isWhat the are are boy dothe the you inmachines workers the see machine here? doing?doing? doing? over cottage industry weaving? This is a picture of workers at the mule- spinning machines making cotton cloth in an English textile mill in 1834. The Textile Industry Invented Textiles: any cloth or goods produced by weaving, knitting or felting. The textile industry developed as a way to solve the problems of the putting-out system (cottage industries) and increase productivity and efficiency. The markets continued to demand more cloth, and the rural workers spinning yarn by hand and weaving cloth on a hand loom could not keep up. Notes: Textile Industry Invented: Cottage industry couldn’t keep up with the demand for textiles. 1767: James Hargreaves invented a compound spinning wheel. It was able to spin 16 threads at one time. He named this invention the Spinning Jenny, after his wife, Jenny. 1769: Richard Arkwright improved on the spinning wheel with his invention of the water frame. This machine involved winding thread through four pairs of rollers operating at varying speeds. What powers the water frame? A water wheel powered the water frame. What might be the advantages of the water frame? What might be the disadvantages of the water frame? 1779: Samuel Crompton made a further improvement on the spinning wheel. By using the mobile carriage of the spinning jenny and the rollers of the water frame, Crompton created a new machine that was able to spin strong yarn, yet also thin enough to be used in the finest fabrics. -

Basic Operations of Spinning (Spun-Yarn from Staple Fibres) Yarn From

29/11/2011 Development of Spinning Modern/Alternative Spinning Technology Hand spinning (twisting & winding) Hugh Gong 拱荣华 Hand spindle Textiles & Paper, School of Materials Spinning wheel (Charkha, India 500 to 1000 AD ) Intermittent Twisting/Drafting and Winding Basic operations of spinning (spun(spun--yarnyarn from staple fibres) Fibre preparation (open/clean/mix) Drafting (reducing thickness) Twisting (strengthening) Winding (building package) Development of Spinning Development of Spinning Hand spinning (twisting, drafting & winding) Hand spinning (twisting & winding) Hand spindle Separate Twisting/Drafting & Winding Hand spindle Spinning wheel (Charkha, India 500 to 1000 AD ) Bobbin-flyer system (Saxony wheel, 1500) Simultaneous Twisting and Winding Thick Yarns 1 29/11/2011 Development of Spinning Hand spinning (twisting & winding) Hand spindle Spinning wheel (Charkha, India 500 to 1000 AD ) Bobbin-flyer system (Saxony wheel, 1500) Roller drafting (Lewis Paul 1738) Separate Drafting from Twisting Continuous Supply of Drafted Strand Development of Spinning Hand spinning (twisting & winding) Hand spindle Spinning wheel (Charkha, India 500 to 1000 AD ) Bobbin-flyer system (Saxony wheel, 1500) Roller drafting (Lewis Paul 1738) Flyer spinning, Richard Arkwright, 1769 Continuous & Fast Production of Yarn 2 29/11/2011 Development of Spinning Hand spinning (twisting & winding) Hand spindle Spinning wheel (Charkha, India 500 to 1000 AD ) Bobbin-flyer system (Saxony wheel, 1500) Roller drafting (Lewis Paul 1738) Flyer spinning, Richard Arkwright, 1769 Spinning Jenny (James Hargreaves, 1764, Pat. 1770) Mule (Samuel Crompton, 1779) Combination of Water Frame (Thomas Highs) and Spinning Jenny Development of Spinning Hand spinning (twisting & winding) Hand spindle Spinning wheel (Charkha, India 500 to 1000 AD ) Bobbin-flyer system (Saxony wheel, 1500) Roller drafting (Lewis Paul 1738) Flyer spinning, Richard Arkwright, 1769 Spinning Jenny (James Hargreaves, 1764, Pat. -

The Textile Mills of Lancashire the Legacy

ISBN 978-1 -907686-24-5 Edi ted By: Rachel Newman Design, Layout, and Formatting: Frtml Cover: Adam Parsons (Top) Tile wcnving shed of Queen Street Mill 0 11 tile day of Published by: its clo~urc, 22 September 2016 Oxford Ar.:haeology North, (© Anthony Pilli11g) Mill 3, Moor Lane Mills, MoorLnJ1e, (Bottom) Tile iconic, Grade Lancaster, /-listed, Queen Street Mill, LAllQD Jlnrlc S.lfke, lire last sun,ini11g example ~fan in fad steam Printed by: powered weaving mill with its Bell & Bain Ltd original loom s in the world 303, Burn field Road, (© Historic England) Thornlieba n k, Glasgow Back Cover: G46 7UQ Tlrt' Beer 1-ln/1 at Hoi till'S Mill, Cfitlwroe ~ Oxford Archaeolog)' Ltd The Textile Mills of Lancashire The Legacy Andy Phelps Richard Gregory Ian Miller Chris Wild Acknowledgements This booklet arises from the historical research and detailed surveys of individual mill complexes carried out by OA North during the Lancashire Textile Mills Survey in 2008-15, a strategic project commissioned and funded by English Heritage (now Historic England). The survey elicited the support of many people, especial thanks being expressed to members of the Project Steering Group, particularly Ian Heywood, for representing the Lancashire Conservation Officers, Ian Gibson (textile engineering historian), Anthony Pilling (textile engineering and architectural historian), Roger Holden (textile mill historian), and Ken Robinson (Historic England). Alison Plummer and Ken Moth are also acknowledged for invaluable contributions to Steering Group discussions. Particular thanks are offered to Darren Ratcliffe (Historic England), who fulfilled the role of Project Assurance Officer and provided considerable advice and guidance throughout the course of the project. -

Bolton Industrial Heritage Trail

Bolton Industrial Heritage Trail Firwood Fold Nasmyth and Wilson Smithills Hall Smithills Dean Road, Bolton, BL1 7NP Bolton, BL2 3AG Steam Hammer Samuel Crompton inventor of the Spinning Mule was born at No. University of Bolton, University Way, Bolton Smithills is one of Bolton's original family homes dating Bolton’s wonderful industrial heritage lives on through its canals, coal, cotton, back to medieval times set in over 2,000 acres of 10 Firwood Fold in 1753. He lived here until 1758, when the BL3 5AB railways and of course its people. Famous Bolton names include Samuel family, moved to nearby Hall i’ th’ Wood. The cottages date from grounds and gardens. Records relating to Smithills Hall Crompton, Fred Dibnah and others whose character, work and inventions have the 17th century and No. 10 had been owned by the Cromptons You can view the steam hammer in the University date from 1335 when William Radcliffe obtained the left an imprint on Bolton. for generations before Samuel was born. A plaque on the cottage grounds which was in use at Thomas Walmsley and manor from the Hulton family. It passed through various (now a private residence) commemorates his birth and there is Sons’ Atlas Forge from 1917 to 1975 to producing families until 1801 when it was bought by the The Bolton Industrial Heritage Trail has 9 main sites of interest including historic also a colourful information panel on the green, interpreting his life, wrought iron. Atlas Forge was the last forge in Britain Ainsworth family, who were successful Bolton buildings, museums and attractions where our history has been preserved for works and the historical significance of Firwood Fold. -

New Lanark Mills – a Brief Introduction

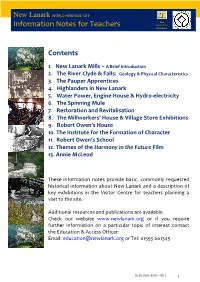

New Lanark WORLD HERITAGE SITE New Information Notes for Teachers Lanark Trust Education Contents 1. New Lanark Mills – A Brief Introduction 2. The River Clyde & Falls: Geology & Physical Characteristics 3. The Pauper Apprentices 4. Highlanders in New Lanark 5. Water Power, Engine House & Hydro-electricity 6. The Spinning Mule 7. Restoration and Revitalisation 8. The Millworkers’ House & Village Store Exhibitions 9. Robert Owen’s House 10. The Institute for the Formation of Character 11. Robert Owen’s School 12. Themes of the Harmony in the Future Film 13. Annie McLeod These information notes provide basic, commonly requested historical information about New Lanark and a description of key exhibitions in the Visitor Centre for teachers planning a visit to the site. Additional resources and publications are available. Check our website www.newlanark.org or if you require further information on a particular topic of interest contact the Education & Access Officer: Email: [email protected] or Tel: 01555 661345 5a.18.1/10c. 03.01 – ED 2 1 2011 1. New Lanark Mills – A Brief Introduction The Old Statistical Account for Lanarkshire records that David Dale (1739-1806) feued the site of New Lanark from Lord Braxfield. It seemed an unlikely location for what was to become the largest cotton manufacturing business in the country, as it was deep in the valley, marshy, and a long way from Glasgow over bad roads. However, there was a plentiful supply of cheap energy provided by the nearby Falls of Clyde, and it was this feature that attracted Dale to the site. In 1784 he brought Richard Arkwright, the inventor of the ‘water frame’ to view the Falls, and they entered into an agreement to establish cotton spinning mills, Dale undertaking the excavation of the mill lade, and the building work, while Arkwright provided the technical training of Dale's men to build and operate the spinning frames. -

Resource Pack

Resource Pack Quarry Bank By Jessica Owens Introduction Quarry Bank is the most complete and least altered factory colony of the Industrial Revolution. It is a site of international importance. The Industrial Revolution of the late 18th century transformed Britain and helped create our modern world. Quarry Bank Mill, founded in 1784 by a young textile merchant, Samuel Greg, was one of the first generation of water-powered cotton spinning mills and thus at the forefront of this revolution. Today, the site remains open as a thriving, living museum, and is a fundamentally important site for educational groups looking to study the Industrial Revolution. This book has been designed as a comprehensive resource for students studying the site. As such, the book has been split into the following seven sections - however, we would encourage you to read through all the sources first, as many can be used to support various lines of investigation. Section 1 Life Pre-Industrial Revolution in Styal Section 2 Why was the Mill built here? Section 3 Life for the Apprentices Section 4 Life for the Workers Section 5 Were the Gregs good employers? Section 6 Typicality of the site Section 7 The development of power at the Mill A note on the National Trust The National Trust is a registered charity, independent of the government. It was founded in 1895 to preserve places, for ever, for everyone. For places: We stand for beautiful and historic places. We look after a breathtaking number and variety of them - each distinctive, memorable and special to people for different reasons.