Our Clarkson Family in England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NETHER WYRESDALE PARISH COUNCIL Agenda for the PC

NETHER WYRESDALE PARISH COUNCIL Agenda for the PC meeting of 6th May 2021, 8PM @ Scorton Chapel Members of the public are to refer to the clerk for items received since the publication of this agenda that require a decision from the parish council at the meeting, e.g. planning matters, finance etc. Clerk: Melanie Harben (01253) 790156 1. Apologies: 2. Declarations of Interest: 3. Minutes from last meeting: To be signed as a correct record. 4. Matters arising (from previous meeting/s): New website Cllr Cottle to provide update. Village enhancement Cllr Drinnan to provide any further update. B4RN Further update to be provided as to whether connectivity has been arranged at Church. Millennium Way audit PC to discuss current progress. Parking issues/traffic on the village Update to be provided regarding any re-arranged meeting with Mark O’Donnell (Highways). Also the use of Church Drive (when not in use), to be discussed in order to provide extra parking provision. Forest of Bowland Wildflowers for the meadows campaign The PC to discuss how to get involved. Children’s play area The PC to discuss any action taken following concerns raised by a member of the public regarding the flooring near the slide and puddle near the bench. Cllr Cottle to report any progress with Mark Billington (Wyre Council). Litter picking equipment The clerk to report the response from Sandra Byrne (Wyre Council) regarding the request to obtain some. Grizedale Bridge repairs Cllr Collinson to provide any update. Wagon Rd surface deterioration (from junct. Tinker’s Lane to Wyreside Hall) The clerk to report the response from Highways including request for reinstatement of the ditch. -

Wyre Settlement Study

Wyre Council Wyre Local Plan Evidence Base Settlement Study August 2016 1 Wyre Council Local Plan Evidence Base - Settlement Study. August 2016 Contents 1. Introduction 2. What is a Settlement? 3. What is a Settlement Hierarchy? 4. The Geography of Wyre – A Summary 5. Methodology 6. Results Appendices Appendix 1 – Population Ranking by Settlement Appendix 2 – Service and Facility Ranking by Settlement Appendix 3 – Transport Accessibility and Connectivity Ranking by Settlement Appendix 4 – Employment Ranking by Settlement Appendix 5 – Overall Settlement Ranking Date: August 2016 2 Wyre Council Local Plan Evidence Base - Settlement Study. August 2016 1. Introduction This study forms part of the evidence base for the Wyre Local Plan. It details research undertaken by the Wyre council planning policy team into the role and function of the borough’s settlements, describing why this work has been undertaken, the methodology used and the results. Understanding the nature of different settlements and the relative roles they can play is critical to developing and delivering local plan strategy and individual policies. With this in mind, the aim of this Settlement Study is two-fold. First, to establish a baseline position in terms of understanding the level of economic and social infrastructure present in each settlement and how this might influence the appropriate nature and scale of development. It will provide evidence for discussions with stakeholders and developers about the nature of supporting infrastructure needed to ensure that future development is sustainable. Second, to identify, analyse and rank the borough’s settlements according to a range of indicators, and by doing so to inform the definition of the local plan settlement hierarchy (see Section 3 below). -

Parish and Town Council Charter for Wyre Had Been Agreed Between Wyre Borough Council and the Local Parish and Town Councils in Wyre

PParisharish aandnd TTownown CCouncilouncil CCharterharter fforor WWyreyre OOctoberctober 22008008 1 2 SIGNATURES Councillor Russell Forsyth Jim Corry Leader Chief Executive Wyre Borough Council Wyre Borough Council Councillor David Sharples Richard Fowler Secretary Chair Lancashire Association of Lancashire Association of Local Councils – Wyre Area Local Councils – Wyre Area Committee Committee 3 CONTENTS Page Introduction 6 A Mutual acknowledgement 8 B General communication and liaison 9 C General support and training 11 D Closer joint governance 12 E Participation and consultation 13 F Town and country planning 15 G Community planning 17 H Financial arrangements 18 I Developing the partnership 19 J Monitoring and review 23 K Complaints 23 L Conclusion 24 M Local council contact 25 Annex 1: Protocol for written consultations 26 Annex 2: Concurrent functions and fi nancial arrangements 28 4 This Parish and Town Council Charter for Wyre had been agreed between Wyre Borough Council and the local parish and town councils in Wyre. For more information about this Charter, please contact: Wyre Borough Council – Joanne Porter, Parish Liaison Offi cer on 01253 887503 or [email protected] Lancashire Association of Local Councils – Wyre Area Committee – Secretary, Councillor David Sharples on (01995) 601701 5 INTRODUCTION Defi nitions: ‘Principal authority’ is Wyre Borough Council. ‘Local councils’ are town and parish councils and parish meetings. 1. The Government is pursuing a number of policies and initiatives that aim to empower local communities and give citizens the opportunity to help shape decisions about the way public services are designed and delivered to them. As part of this agenda the Government recognises that democratically elected town and parish councils - the most local tier of local government - can play a key role in meeting this aim. -

Chetham Miscellanies

942.7201 M. L. C42r V.19 1390748 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00728 8746 REMAINS HISTORICAL k LITERARY NOTICE. The Council of the Chetham Society have deemed it advisable to issue as a separate Volume this portion of Bishop Gastrell's Notitia Cestriensis. The Editor's notice of the Bishop will be added in the concluding part of the work, now in the Press. M.DCCC.XLIX. REMAINS HISTORICAL & LITERARY CONNECTED WITH THE PALATINE COUNTIES OF LANCASTER AND CHESTER PUBLISHED BY THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. VOL. XIX. PRINTED FOR THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. M.DCCC.XLIX. JAMES CROSSLEY, Esq., President. REV. RICHARD PARKINSON, B.D., F.S.A., Canon of Manchester and Principal of St. Bees College, Vice-President. WILLIAM BEAMONT. THE VERY REV. GEORGE HULL BOWERS, D.D., Dean of Manchester. REV. THOMAS CORSER, M.A. JAMES DEARDEN, F.S.A. EDWARD HAWKINS, F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S. THOMAS HEYWOOD, F.S.A. W. A. HULTON. REV. J. PICCOPE, M.A. REV. F. R. RAINES, M.A., F.S.A. THE VEN. JOHN RUSHTON, D.D., Archdeacon of Manchester. WILLIAM LANGTON, Treasurer. WILLIAM FLEMING, M.D., Hon. SECRETARY. ^ ^otttia €mtvitmis, HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE DIOCESE OF CHESTER, RIGHT REV. FRANCIS GASTRELL, D.D. LORD BISHOP OF CHESTER. NOW FIRST PEINTEB FROM THE OEIGINAl MANITSCEIPT, WITH ILLrSTBATIVE AND EXPLANATOEY NOTES, THE REV. F. R. RAINES, M.A. F.S.A. BUBAL DEAN OF ROCHDALE, AND INCUMBENT OF MILNEOW. VOL. II. — PART I. ^1 PRINTED FOR THE GHETHAM SOCIETY. M.DCCC.XLIX. 1380748 CONTENTS. VOL. II. — PART I i¥lamf)e£{ter IBeanerp* page. -

Appendix 5 Fylde

FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 LANCASTER - GARSTANG - POULTON - BLACKPOOL 42 via Galgate - Great Eccleston MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ LANCASTER Bus Station 1900 2015 2130 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 1909 2024 2139 LANCASTER University Gates 1912 2027 2142 GALGATE Crossroads 1915 2030 2145 CABUS Hamilton Arms 1921 2036 2151 GARSTANG Bridge Street 1926 2041 2156 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 1935 2050 2205 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 1939 2054 2209 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 1943 2058 2213 POULTON St Chads Church 1953 2108 2223 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 1958 2113 2228 BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2010 2125 2240 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council BLACKPOOL - POULTON - GARSTANG - LANCASTER 42 via Great Eccleston - Galgate MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2015 2130 2245 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 2020 2135 2250 POULTON Teanlowe Centre 2032 2147 2302 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 2042 2157 2312 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 2047 2202 2317 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 2051 2206 2321 GARSTANG Park Hill Road 2059 2214 2329 CABUS Hamilton Arms 2106 2221 2336 GALGATE Crossroads 2112 2227 2342 LANCASTER University Gates 2115 2230 2345 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 2118 2233 2348 LANCASTER Bus Station 2127 2242 2357 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council LIST OF ALTERNATIVE TRANSPORT SERVICES AVAILABLE – Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 2 between Lancaster and University Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 40 between Lancaster and Garstang (limited) Blackpool Transport Service 2 between Poulton and Blackpool FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 PRESTON - LYTHAM - ST. -

Forest of Bowland AONB Annual Report 2017

Annual Report 2016-2017 FOREST OF BOWLAND Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty www.forestofbowland.com Contents View from the Chair 03 A Strong Connection Between Natural & Cultural Heritage People & The Landscape Pendle Hill Landscape Partnership Scheme 04 Discovery Guide 15 Undergrounding for Visual Amenity 05 Communication Projects 16 Traditional Boundaries 06 Wyre Coast and Countryside Service - Enjoying 17 9,000 Reasons to Thank Festival Bowland 18 Ribble Rivers Trust Volunteers 07 Promoted Routes 19 Street Lakes – Morphology Improvements 08 Working in Partnership Peatland Restoration 09 AONB Networks 20 Wyre Coast and Countryside Service – Looking After 10 Financial Summary 22 Wildflowers for the Meadows 11 Membership 23 Resilient & Sustainable Communities Contacts 25 Bowland Experience 12 Champion Bowland 13 LEWFA Hyperfast Broadband 14 Common Darter, Lune Cover Image - River Hodder at Whitewell © Steven Kidd © Chris Burscough www.forestofbowland.com 2 Annual Report 2016 - 2017 View from the Chair You will no doubt by now be well aware of the AONB Partnership's plans for the Pendle Hill Landscape Partnership Scheme in 2018. But you may not have realised that our graduate placement, Jayne Ashe, has made a head start and has been busy supporting and co-ordinating a new 'Pendle Hill Volunteers Group' over the last year. The volunteers have been able to carry out small-scale tasks to improve the local environment of the hill, including woodland management, surveying, removal of invasives and hedgelaying amongst other things. We see this group growing and developing as the Pendle Hill LP begins its delivery phase next year. Ribble Rivers Trust have been going from strength to strength recently, with new initiatives and projects sprouting up across the AONB, including the ambitious and exciting 'Ribble Life Together' catchment- wide initiative and the River Loud Farmer Facilitation Group. -

Belper Mills Site

Belper North Mill Trust Outline masterplan for the renewal of the Belper Mills site February 2017 Belper North Mill Trust Outline masterplan for the renewal of the Belper Mills site Contents Page numbers 1 Introduction 1 2 Heritage significance 1 - 4 3 End uses 4 - 5 4 Development strategy 5 - 9 4.1 Phase 1 6 - 7 4.2 Phase 2 7 4.3 Phase 3 8 4.4 The end result 9 5 Costs of realisation 10 - 11 6 Potential financing – capital and revenue 11 - 15 6.1 Capital/realisation 11 - 12 6.2 Revenue sustainability 12 - 15 7 Delivery 15 - 16 Appendices 1 Purcell's Statement of Significance 2 Purcell's Feasibility Study Belper North Mill Trust Outline masterplan for the renewal of the Belper Mills site 1 Introduction As part of this phase of work for the Belper North Mill Trust we have, with Purcell Architects, carried out an outline masterplanning exercise for the whole Belper Mills site. At the outset, it is important to say that at the moment the site is privately owned and that while Amber Valley Borough Council initiated a Compulsory Purchase Order process in 2015, that process is still at a preliminary stage. This is a preliminary overview, based on the best available, but limited, information. In particular, access to the buildings on site has been limited; while a considerable amount of the North Mill is accessible because it is occupied, access to the East Mill, now empty, was not made available to us. Also, while we have undertaken some stakeholder consultation, we have not at this stage carried out wider consultation or public engagement, nor have we undertaken detailed market research, all of which would be essential to any next stage planning for the future of the site. -

42 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

42 bus time schedule & line map 42 Blackpool Town Centre View In Website Mode The 42 bus line (Blackpool Town Centre) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blackpool Town Centre: 5:25 AM - 5:42 PM (2) Lancaster City Centre: 6:53 AM - 5:50 PM (3) White Lund: 6:33 PM - 7:24 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 42 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 42 bus arriving. Direction: Blackpool Town Centre 42 bus Time Schedule 101 stops Blackpool Town Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 10:10 AM - 5:10 PM Monday 5:25 AM - 5:42 PM Homfray Avenue, White Lund Tuesday 5:25 AM - 5:42 PM Morecambe Road School, White Lund Wednesday 5:25 AM - 5:42 PM Lancaster And Morecambe College, White Lund Thursday 5:25 AM - 5:42 PM Penrhyn Road, Scale Hall Friday 5:25 AM - 5:42 PM Scale Hall Saturday 6:45 AM - 5:42 PM Morecambe Road, England Summersgill Road, Scale Hall Carlisle Bridge, Ryelands 42 bus Info Wenning Place, Lancaster Direction: Blackpool Town Centre Stops: 101 Our Ladys Rchs, Skerton Trip Duration: 96 min Line Summary: Homfray Avenue, White Lund, Red Cross, Skerton Morecambe Road School, White Lund, Lancaster And Morecambe College, White Lund, Penrhyn Road, Parliament Street, Lancaster City Centre Scale Hall, Scale Hall, Summersgill Road, Scale Hall, Carlisle Bridge, Ryelands, Our Ladys Rchs, Skerton, 32 Parliament Street, Lancaster Red Cross, Skerton, Parliament Street, Lancaster City Centre, Sainsburys, Lancaster City Centre, Bus Sainsburys, Lancaster City Centre Station, Lancaster City Centre, -

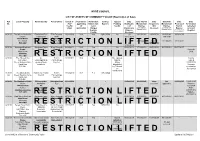

ASSETS of COMMUNITY VALUE (Restriction of Sale)

WYRE COUNCIL LIST OF ASSETS OF COMMUNITY VALUE (Restriction of Sale) Ref Land/ Property Nominated by Asset Owner Listed as Reason for Restriction Listing Appeal Date Date Interim Date Date Full Date Date No. ACV not listing Entered on Expires Pending Notificatio Moratorium Request to Moratorium Protected Restriction Yes/No (if Land Yes/No n of Expires Bid Expires Period cancelled (date) applicable) Charges Intention to (6 weeks from Received (6 months from Expires on Land Disposal Notice) Disposal Notice) Register Dispose (18 months from Register Disposal Notice) Yes/No Received ACV:01 The Mount Methodist Fleetwood Plus The Trustees 29/11/2013 N/A Yes 29/11/2018 No (1) 30/01/2014 12/01/2014 19/06/2014 19/06/2015 Church, Community of the 19/12/2013 (not sold) Mount Road, Interest Company Methodist Fleetwood (Co. No. Church, North 28/06/2016 NO BID 17/11/2016 17/11/2017 FY7 6QZ R8597908) E SFylde CircuitT R I C T I O N L I (2)F T E RECEIVEDD 17/05/2016 ACV:02 Garstang Business Garstang Town Wyre Borough 06/02/2014 N/A Yes - No 06/01/2016 17/02/2016 28/01/2016 06/07/2016 06/07/2017 Centre Council Council Property High Street Sold Garstang PR3 1EB R E S T R I C T I O N L I F T E D ACV:03 The Shovels Inn An Punch 22/10/2014 N/A Yes No. Appeal Listing Kiln Lane/ unincorporated Partnerships against expired Green Meadow Lane group of local Limited listing 22/10/2019 Hambleton residents dismissed See new FY6 9AL by Tribunal nomination on ACV:03(a) 02/06/2015 ACV:03 The Shovels Inn Hambleton Parish Punch 13/12/2019 N/A Yes 13/12/2024 (a) Green -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87370-3 - Heroes of Invention: Technology, Liberalism and British Identity, 1750-1914 Christine MacLeod Frontmatter More information Heroes of Invention This innovative study adopts a completely new perspective on both the industrial revolution and nineteenth-century British culture. It investi- gates why inventors rose to heroic stature and popular acclaim in Victorian Britain, attested by numerous monuments, biographies and honours, and contends there was no decline in the industrial nation’s self-esteem before 1914. In a period notorious for hero-worship, the veneration of inventors might seem unremarkable, were it not for their previous disparagement and the relative neglect suffered by their twentieth-century successors. Christine MacLeod argues that inventors became figureheads for various nineteenth-century factions, from economic and political liberals to impoverished scientists and radical artisans, who deployed their heroic reputation to challenge the aristocracy’s hold on power and the militaristic national identity that bolstered it. Although this was a challenge that ultimately failed, its legacy for present-day ideas about invention, inventors and the history of the industrial revolution remains highly influential. CHRISTINE MACLEOD is Professor of History in the School of Humanities, University of Bristol. She is the author of Inventing the Industrial Revolution: The English Patent System, 1660–1800 (1988). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87370-3 -

Prices and Profits in Cotton Textiles During the Industrial Revolution C

PRICES AND PROFITS IN COTTON TEXTILES DURING THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION C. Knick Harley PRICES AND PROFITS IN COTTON TEXTILES DURING THE 1 INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION C. Knick Harley Department of Economics and St. Antony’s College University of Oxford Oxford OX2 6JF UK <[email protected]> Abstract Cotton textile firms led the development of machinery-based industrialization in the Industrial Revolution. This paper presents price and profits data extracted from the accounting records of three cotton firms between the 1770s and the 1820s. The course of prices and profits in cotton textiles illumine the nature of the economic processes at work. Some historians have seen the Industrial Revolution as a Schumpeterian process in which discontinuous technological change created large profits for innovators and succeeding decades were characterized by slow diffusion. Technological secrecy and imperfect capital markets limited expansion of use of the new technology and output expanded as profits were reinvested until eventually the new technology dominated. The evidence here supports a more equilibrium view which the industry expanded rapidly and prices fell in response to technological change. Price and profit evidence indicates that expansion of the industry had led to dramatic price declines by the 1780s and there is no evidence of super profits thereafter. Keywords: Industrial Revolution, cotton textiles, prices, profits. JEL Classification Codes: N63, N83 1 I would like to thank Christine Bies provided able research assistance, participants in the session on cotton textiles for the XII Congress of the International Economic Conference in Madrid, seminars at Cambridge and Oxford and Dr Tim Leung for useful comments. -

Forest of Bowland AONB Access Land

Much of the new Access Land in Access Land will be the Forest of Bowland AONB is identified with an Access within its Special Protection Area Land symbol, and may be accessed by any bridge, stile, gate, stairs, steps, stepping stone, or other (SPA). works for crossing water, or any gap in a boundary. Such access points will have This European designation recognises the importance of the area’s upland heather signage and interpretation to guide you. moorland and blanket bog as habitats for upland birds. The moors are home to many threatened species of bird, including Merlin, Golden Plover, Curlew, Ring If you intend to explore new Parts of the Forest of Bowland Ouzel and the rare Hen Harrier, the symbol of the AONB. Area of Outstanding Natural access land on foot, it is important that you plan ahead. Beauty (AONB) are now For the most up to date information and what local restrictions may accessible for recreation on foot be in place, visit www.countrysideaccess.gov.uk or call the Open Access Helpline on 0845 100 3298 for the first time to avoid disappointment. Once out and about, always follow local signs because the Countryside & Rights of Way Act (CRoW) 2000 gives people new and advice. rights to walk on areas of open country and registered common land. Access may be excluded or restricted during Heather moorland is Many people exceptional weather or ground conditions Access Land in the for the purpose of fire prevention or to avoid danger to the public. Forest of Bowland itself a rare habitat depend on - 75% of all the upland heather moorland in the the Access AONB offers some of world and 15% of the global resource of blanket bog are to be found in Britain.