New Lanark Mills – a Brief Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intimations Surnames

Intimations Extracted from the Watt Library index of family history notices as published in Inverclyde newspapers between 1800 and 1918. Surnames H-K This index is provided to researchers as a reference resource to aid the searching of these historic publications which can be consulted on microfiche, preferably by prior appointment, at the Watt Library, 9 Union Street, Greenock. Records are indexed by type: birth, death and marriage, then by surname, year in chronological order. Marriage records are listed by the surnames (in alphabetical order), of the spouses and the year. The copyright in this index is owned by Inverclyde Libraries, Museums and Archives to whom application should be made if you wish to use the index for any commercial purpose. It is made available for non- commercial use under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 License). This document is also available in Open Document Format. Surnames H-K Record Surname When First Name Entry Type Marriage HAASE / LEGRING 1858 Frederick Auguste Haase, chief steward SS Bremen, to Ottile Wilhelmina Louise Amelia Legring, daughter of Reverend Charles Legring, Bremen, at Greenock on 24th May 1858 by Reverend J. Nelson. (Greenock Advertiser 25.5.1858) Marriage HAASE / OHLMS 1894 William Ohlms, hairdresser, 7 West Blackhall Street, to Emma, 4th daughter of August Haase, Herrnhut, Saxony, at Glengarden, Greenock on 6th June 1894 .(Greenock Telegraph 7.6.1894) Death HACKETT 1904 Arthur Arthur Hackett, shipyard worker, husband of Mary Jane, died at Greenock Infirmary in June 1904. (Greenock Telegraph 13.6.1904) Death HACKING 1878 Samuel Samuel Craig, son of John Hacking, died at 9 Mill Street, Greenock on 9th January 1878. -

City of Glasgow and Clyde Valley 3 Day Itinerary

The City of Glasgow and The Clyde Valley Itinerary - 3 Days 01. Kelvin Hall The Burrell Collection A unique partnership between Glasgow Life, the University of The famous Burrell Collection, one of the greatest art collections Glasgow and the National Library of Scotland has resulted in this ever amassed by one person and consisting of more than 8,000 historic building being transformed into an exciting new centre of objects, will reopen in Spring 2021. Housed in a new home in cultural excellence. Your clients can visit Kelvin Hall for free and see Glasgow’s Pollok Country Park, the Burrell’s renaissance will see the National Library of Scotland’s Moving Image Archive or take a the creation of an energy efficient, modern museum that will tour of the Glasgow Museums’ and the Hunterian’s store, alongside enable your clients to enjoy and better connect with the collection. enjoy a state-of-the art Glasgow Club health and fitness centre. The displays range from work by major artists including Rodin, Degas and Cézanne. 1445 Argyle Street Glasgow, G3 8AW Pollok Country Park www.kelvinhall.org.uk 2060 Pollokshaws Road Link to Trade Website Glasgow. G43 1AT www.glasgowlife.org.uk Link to Trade Website Distance between Kelvin Hall and Clydeside Distillery is 1.5 miles/2.4km Distance between The Burrell Collection and Glasgow city centre The Clydeside Distillery is 5 miles/8km The Clydeside Distillery is a Single Malt Scotch Whisky distillery, visitor experience, café, and specialist whisky shop in the heart of Glasgow. At Glasgow’s first dedicated Single Malt Scotch Whisky Distillery for over 100 years, your clients can choose a variety of tours, including whisky and chocolate paring. -

Scotland's Historic Cities D N a L T O C

Scotland's Historic Cities D N A L T O C Tinto Hotel S Holiday Inn Edinburgh Edinburgh Castle ©Paul Tompkins,Scottish ViewPoint 5 DAYS from only £142 Tinto Hotel Holiday Inn Edinburgh NEW What To Do Biggar Edinburgh Edinburgh Scotland’s capital offers endless possibilities including DOUBLE FOR TRADITIONAL DOUBLE FOR Edinburgh Castle, Royal Yacht Britannia, The Queen’s EXCELLENT SINGLE SCOTTISH SINGLE official Scottish residence – The Palace of Holyroodhouse PUBLIC AREAS and the Scotch Whisky Heritage Centre. The Royal Mile, OCCUPANCY HOTEL OCCUPANCY the walk of kings and queens, between Edinburgh Castle and Holyrood Palace is a must to enjoy Edinburgh at its historical best. If the modern is more for you, then the This charming 3 star property was originally built as a This 4 star Holiday Inn is located on the main road to shops and Georgian buildings of Princes Street are railway hotel and has undergone refurbishment to return it Edinburgh city centre being only 2 miles from Princes Street. perfect for those browsing for a bargain! to its former glory. With wonderfully atmospheric public This hotel has a spacious modern open plan reception, areas and a large entertainment area, this small hotel is restaurant, lounge and bar. All 303 air conditioned Glasgow deceptively large. Each of the 40 bedrooms is traditionally bedrooms are equipped with tea/coffee making facilities and Scotland’s second city has much to offer the visitor. furnished with facilities including TV, hairdryer, and TV. Leisure facilities within the hotel include swimming pool, Since its regeneration, Glasgow is now one of the most tea/coffee making facilities. -

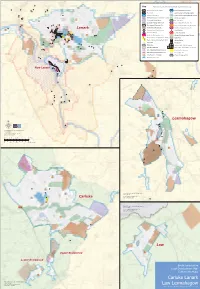

Carluke Lanark Law Lesmahagow

Key Please note: Not all of the Key elements will be present on each map South Lanarkshire Boundary Local Neighbourhood Centre River Clyde Out of Centre Commercial Location Settlement Boundary Retail / Comm Proposal Outwith Centres Strategic Economic Investment Location Priority Greenspace Community Growth Area Green Network Structural Planting within CGA New Lanark World Heritage Site Development Framework Site New Lanark World Heritage Site Buffer Lanark Residential Masterplan Site Scheduled Ancient Monument ² Primary School Modernisation Listed Building ² Secondary School Conservation Area Air Quality Management Area Morgan Glen Local Nature Reserve ±³d Electric Vehicle Charging Point (43kW) Quiet Area ±³d Electric Vehicle Charging Point (7kW) Railway Station Green Belt Bus Station Rural Area Park and Ride / Rail Interchange General Urban Area Park & Ride / Rail and Bus Interchange Core Industrial and Business Area New Road Infrastructure Other Employment Land Use Area Recycling Centre 2014 Housing Land Supply Waste Management Site Strategic Town Centre New Lanark Lesmahagow ÅN Scheduled Monuments and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Ordnance Survey 100020730 0 0.125 0.25 0.5 Miles 0 0.2 0.4 0.8 Kilometers Scheduled Monuments, and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Carluke Ordnance Survey 100020730 Scheduled Monuments, and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Ordnance Survey 100020730 Law Upper Braidwood Lower Braidwood South Lanarkshire Local Development Plan Settlements Maps Carluke Lanark Scheduled Monuments, and Listed Building information © Historic Scotland. © Crown copyright and database rights 2015. Ordnance Survey 100020730 Law Lesmahagow Larkhall, Hamilton, Blantyre, Uddingston, Bothwell, on reverse. -

South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010)

South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010) 2010 Air Quality Progress Report for South Lanarkshire Council In fulfillment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management Date (August, 2010) Progress Report i Date (August, 2010) South Lanarkshire Council - Scotland ii Progress Report South Lanarkshire Council – Scotland Date (August, 2010) Local Ann Crossar Authority Officer Department Community Resources, Environmental Services Address 1st Floor Atholl House, East Kilbride, G74 1LU Telephone 01355 806509 e-mail [email protected]. uk Report G_SLC_006_Progress Report Reference number Date July 2010 Progress Report iii Date (August, 2010) South Lanarkshire Council - Scotland Executive Summary A review of new pollutant monitoring data and atmospheric emission sources within the South Lanarkshire Council area has been undertaken. The assessment compared the available monitoring data to national air quality standards in order to identify any existing exceedences of the standards. Data was gathered from various national and local sources with regard to atmospheric emissions from: road traffic; rail; aircraft; shipping; industrial processes; intensive farming operations; domestic properties; biomass plants; and dusty processes. The screening methods outlined in the technical guidance were used to determine the likelihood that a particular source would result in an exceedence of national air quality standards. The review of new and changed emission sources identified no sources that were likely to -

Park Keeper's Cottage Carstairs Junction, Lanark

Park Keeper’s Cottage Carstairs Junction, Lanark Remains of cottage and site with potential to rebuild rural dwelling house. LAWRIE & SYMINGTON LIMITED , LANARK AG RICULTURAL CENTRE , MUIRG LEN , LANARK , ML 11 9AX TEL : 01555 662281 FAX : 01555 665638/665100 EMAIL : property@lawrie-a nd-s ymington.com WEB SITE : www.la wrie-and-symington.com Directions: Inspection: From Carstairs Village take Carstairs Inspection of the subjects are strictly by Road heading for Carstairs Junction. appointment only on telephoning the Sole After leaving the village the property is Selling Agents, Lawrie & Symington first on the left approximately half a mile Limited, Lanark. Tel: 01555 662281. on. Note: Situation: The seller is not bound to accept the The subjects are situated on the outskirts highest or any offer. of Carstairs Junction adjacent to the bowling green and football field. The foregoing particulars whilst believed to be correct are in no way guaranteed Description: and offerers shall be held to have Remains of stone built cottage with only satisfied them selves in all respects. the four exterior walls still standing, situated within its own garden ground. Any error or omission shall not annul the sale of the property, or entitle any party Access: to com pensation, nor in any Access to the property is by private circum stances give ground for action at driveway. Law. Planning: There is no planning consent to rebuild dwelling at present. Services: There are no services on the subjects although they are nearby. Title Deeds: The Title Deeds m ay be inspected at the offices of Freelands, 139 Main Street, Wishaw, ML2 7AU. -

National Programme 2017/2018 2

National Programme 2017/2018 2 National Programme 2017/2018 3 National Programme 2017/2018 National Programme 2017/2018 1 National Programme Across Scotland Through our National Strategy 2016–2020, Across Scotland, Working to Engage and Inspire, we are endeavouring to bring our collections, expertise and programmes to people, museums and communities throughout Scotland. In 2017/18 we worked in all of Scotland’s 32 local authority areas to deliver a wide-ranging programme which included touring exhibitions and loans, community engagement projects, learning and digital programmes as well as support for collections development through the National Fund for Acquisitions, expert advice from our specialist staff and skills development through our National Training Programme. As part of our drive to engage young people in STEM learning (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths), we developed Powering Up, a national science engagement programme for schools. Funded by the ScottishPower Foundation, we delivered workshops on wind, solar and wave energy in partnership with the National Mining Museum, the Scottish Maritime Museum and New Lanark World Heritage Site. In January 2017, as part of the final phase of redevelopment of the National Museum of Scotland, we launched an ambitious national programme to support engagement with Ancient Egyptian and East Asian collections held in museums across Scotland. Funded by the National Lottery and the Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund, the project is providing national partnership exhibitions and supporting collection reviews, skills development and new approaches to audience engagement. All of this work is contributing to our ambition to share our collections and expertise as widely as possible, ensuring that we are a truly national museum for Scotland. -

Belper Mills Site

Belper North Mill Trust Outline masterplan for the renewal of the Belper Mills site February 2017 Belper North Mill Trust Outline masterplan for the renewal of the Belper Mills site Contents Page numbers 1 Introduction 1 2 Heritage significance 1 - 4 3 End uses 4 - 5 4 Development strategy 5 - 9 4.1 Phase 1 6 - 7 4.2 Phase 2 7 4.3 Phase 3 8 4.4 The end result 9 5 Costs of realisation 10 - 11 6 Potential financing – capital and revenue 11 - 15 6.1 Capital/realisation 11 - 12 6.2 Revenue sustainability 12 - 15 7 Delivery 15 - 16 Appendices 1 Purcell's Statement of Significance 2 Purcell's Feasibility Study Belper North Mill Trust Outline masterplan for the renewal of the Belper Mills site 1 Introduction As part of this phase of work for the Belper North Mill Trust we have, with Purcell Architects, carried out an outline masterplanning exercise for the whole Belper Mills site. At the outset, it is important to say that at the moment the site is privately owned and that while Amber Valley Borough Council initiated a Compulsory Purchase Order process in 2015, that process is still at a preliminary stage. This is a preliminary overview, based on the best available, but limited, information. In particular, access to the buildings on site has been limited; while a considerable amount of the North Mill is accessible because it is occupied, access to the East Mill, now empty, was not made available to us. Also, while we have undertaken some stakeholder consultation, we have not at this stage carried out wider consultation or public engagement, nor have we undertaken detailed market research, all of which would be essential to any next stage planning for the future of the site. -

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010

Allied Social Science Associations Atlanta, GA January 3–5, 2010 Contract negotiations, management and meeting arrangements for ASSA meetings are conducted by the American Economic Association. i ASSA_Program.indb 1 11/17/09 7:45 AM Thanks to the 2010 American Economic Association Program Committee Members Robert Hall, Chair Pol Antras Ravi Bansal Christian Broda Charles Calomiris David Card Raj Chetty Jonathan Eaton Jonathan Gruber Eric Hanushek Samuel Kortum Marc Melitz Dale Mortensen Aviv Nevo Valerie Ramey Dani Rodrik David Scharfstein Suzanne Scotchmer Fiona Scott-Morton Christopher Udry Kenneth West Cover Art is by Tracey Ashenfelter, daughter of Orley Ashenfelter, Princeton University, former editor of the American Economic Review and President-elect of the AEA for 2010. ii ASSA_Program.indb 2 11/17/09 7:45 AM Contents General Information . .iv Hotels and Meeting Rooms ......................... ix Listing of Advertisers and Exhibitors ................xxiv Allied Social Science Associations ................. xxvi Summary of Sessions by Organization .............. xxix Daily Program of Events ............................ 1 Program of Sessions Saturday, January 2 ......................... 25 Sunday, January 3 .......................... 26 Monday, January 4 . 122 Tuesday, January 5 . 227 Subject Area Index . 293 Index of Participants . 296 iii ASSA_Program.indb 3 11/17/09 7:45 AM General Information PROGRAM SCHEDULES A listing of sessions where papers will be presented and another covering activities such as business meetings and receptions are provided in this program. Admittance is limited to those wearing badges. Each listing is arranged chronologically by date and time of the activity; the hotel and room location for each session and function are indicated. CONVENTION FACILITIES Eighteen hotels are being used for all housing. -

Marketing Fragment 6 X 10.T65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87370-3 - Heroes of Invention: Technology, Liberalism and British Identity, 1750-1914 Christine MacLeod Frontmatter More information Heroes of Invention This innovative study adopts a completely new perspective on both the industrial revolution and nineteenth-century British culture. It investi- gates why inventors rose to heroic stature and popular acclaim in Victorian Britain, attested by numerous monuments, biographies and honours, and contends there was no decline in the industrial nation’s self-esteem before 1914. In a period notorious for hero-worship, the veneration of inventors might seem unremarkable, were it not for their previous disparagement and the relative neglect suffered by their twentieth-century successors. Christine MacLeod argues that inventors became figureheads for various nineteenth-century factions, from economic and political liberals to impoverished scientists and radical artisans, who deployed their heroic reputation to challenge the aristocracy’s hold on power and the militaristic national identity that bolstered it. Although this was a challenge that ultimately failed, its legacy for present-day ideas about invention, inventors and the history of the industrial revolution remains highly influential. CHRISTINE MACLEOD is Professor of History in the School of Humanities, University of Bristol. She is the author of Inventing the Industrial Revolution: The English Patent System, 1660–1800 (1988). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87370-3 -

Prices and Profits in Cotton Textiles During the Industrial Revolution C

PRICES AND PROFITS IN COTTON TEXTILES DURING THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION C. Knick Harley PRICES AND PROFITS IN COTTON TEXTILES DURING THE 1 INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION C. Knick Harley Department of Economics and St. Antony’s College University of Oxford Oxford OX2 6JF UK <[email protected]> Abstract Cotton textile firms led the development of machinery-based industrialization in the Industrial Revolution. This paper presents price and profits data extracted from the accounting records of three cotton firms between the 1770s and the 1820s. The course of prices and profits in cotton textiles illumine the nature of the economic processes at work. Some historians have seen the Industrial Revolution as a Schumpeterian process in which discontinuous technological change created large profits for innovators and succeeding decades were characterized by slow diffusion. Technological secrecy and imperfect capital markets limited expansion of use of the new technology and output expanded as profits were reinvested until eventually the new technology dominated. The evidence here supports a more equilibrium view which the industry expanded rapidly and prices fell in response to technological change. Price and profit evidence indicates that expansion of the industry had led to dramatic price declines by the 1780s and there is no evidence of super profits thereafter. Keywords: Industrial Revolution, cotton textiles, prices, profits. JEL Classification Codes: N63, N83 1 I would like to thank Christine Bies provided able research assistance, participants in the session on cotton textiles for the XII Congress of the International Economic Conference in Madrid, seminars at Cambridge and Oxford and Dr Tim Leung for useful comments. -

Acquiring Knowledge Outside the Academy in Early Modern England

Patrick Wallis Between apprenticeship and skill: acquiring knowledge outside the academy in Early Modern England Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Wallis, Patrick (2018) Between apprenticeship and skill: acquiring knowledge outside the academy in Early Modern England. Science in Context. ISSN 0269-8897 (In Press) © 2018 University of Cambridge This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/88579/ Available in LSE Research Online: June 2018 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Between Apprenticeship and Skill: Acquiring Knowledge outside the academy in Early Modern England Patrick Wallis Argument Apprenticeship was probably the largest mode of organized learning in early modern European societies, and artisan practitioners commonly began as apprentices. Yet little is known about how youths actually gained skills. I develop a model of vocational pedagogy that accounts for the characteristics of apprenticeship and use a range of legal and autobiographical sources to examine the contribution of different forms of training in England.