The Changing Dynamics of Twenty-First-Century Space Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules for the Heavens: the Coming Revolution in Space and the Laws of War

RULES FOR THE HEAVENS: THE COMING REVOLUTION IN SPACE AND THE LAWS OF WAR John Yoo* Great powers are increasing their competition in space. Though Russia and the United States have long relied on satellites for surveillance of rival nations’ militaries and the detection of missile launches, the democratization of space through technological advancements has allowed other nations to assert greater control. This Article addresses whether the United States and other nations should develop the space-based weapons that these policies promise, or whether they should cooperate to develop new international agreements to ban them. In some areas of space, proposals for regulation have already come too late. The U.S.’s nuclear deterrent itself depends cru- cially on space: ballistic missiles leave and then re-enter the atmosphere, giving them a global reach without serious defense. As more nations develop nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) technology, outer space will become even more important as an arena for defense against weapons of mass destruction (WMD) proliferation. North Korea’s progress on ICBM and nuclear technology, for example, will prompt even greater in- vestment in space-based missile defense systems. This Article makes two contributions. First, it argues against a grow- ing academic consensus in favor of a prohibition on military activities in space. It argues that these scholars over-read existing legal instruments and practice. While nations crafted international agreements to bar WMDs in outer space, they carefully left unregulated reconnaissance and commu- nications satellites, space-based conventional weapons, antisatellite sys- tems, and even WMDs that transit through space, such as ballistic missiles. -

SPEAKERS TRANSPORTATION CONFERENCE FAA COMMERCIAL SPACE 15TH ANNUAL John R

15TH ANNUAL FAA COMMERCIAL SPACE TRANSPORTATION CONFERENCE SPEAKERS COMMERCIAL SPACE TRANSPORTATION http://www.faa.gov/go/ast 15-16 FEBRUARY 2012 HQ-12-0163.INDD John R. Allen Christine Anderson Dr. John R. Allen serves as the Program Executive for Crew Health Christine Anderson is the Executive Director of the New Mexico and Safety at NASA Headquarters, Washington DC, where he Spaceport Authority. She is responsible for the development oversees the space medicine activities conducted at the Johnson and operation of the first purpose-built commercial spaceport-- Space Center, Houston, Texas. Dr. Allen received a B.A. in Speech Spaceport America. She is a recently retired Air Force civilian Communication from the University of Maryland (1975), a M.A. with 30 years service. She was a member of the Senior Executive in Audiology/Speech Pathology from The Catholic University Service, the civilian equivalent of the military rank of General of America (1977), and a Ph.D. in Audiology and Bioacoustics officer. Anderson was the founding Director of the Space from Baylor College of Medicine (1996). Upon completion of Vehicles Directorate at the Air Force Research Laboratory, Kirtland his Master’s degree, he worked for the Easter Seals Treatment Air Force Base, New Mexico. She also served as the Director Center in Rockville, Maryland as an audiologist and speech- of the Space Technology Directorate at the Air Force Phillips language pathologist and received certification in both areas. Laboratory at Kirtland, and as the Director of the Military Satellite He joined the US Air Force in 1980, serving as Chief, Audiology Communications Joint Program Office at the Air Force Space at Andrews AFB, Maryland, and at the Wiesbaden Medical and Missile Systems Center in Los Angeles where she directed Center, Germany, and as Chief, Otolaryngology Services at the the development, acquisition and execution of a $50 billion Aeromedical Consultation Service, Brooks AFB, Texas, where portfolio. -

Chapter Fourteen Men Into Space: the Space Race and Entertainment Television Margaret A. Weitekamp

CHAPTER FOURTEEN MEN INTO SPACE: THE SPACE RACE AND ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION MARGARET A. WEITEKAMP The origins of the Cold War space race were not only political and technological, but also cultural.1 On American television, the drama, Men into Space (CBS, 1959-60), illustrated one way that entertainment television shaped the United States’ entry into the Cold War space race in the 1950s. By examining the program’s relationship to previous space operas and spaceflight advocacy, a close reading of the 38 episodes reveals how gender roles, the dangers of spaceflight, and the realities of the Moon as a place were depicted. By doing so, this article seeks to build upon and develop the recent scholarly investigations into cultural aspects of the Cold War. The space age began with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. But the space race that followed was not a foregone conclusion. When examining the United States, scholars have examined all of the factors that led to the space technology competition that emerged.2 Notably, Howard McCurdy has argued in Space and the American Imagination (1997) that proponents of human spaceflight 1 Notably, Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rocket’s Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957, Cambridge Centennial of Flight (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) offers the first history of the social and cultural contexts of Soviet science and the military rocket program. Alexander C. T. Geppert, ed., Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) resulted from a conference examining the intersections of the social, cultural, and political histories of spaceflight in the Western European context. -

Retrofuture Hauntings on the Jetsons

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Queens College 2020 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello CUNY Graduate Center How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/qc_pubs/446 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] de genere Rivista di studi letterari, postcoloniali e di genere Journal of Literary, Postcolonial and Gender Studies http://www.degenere-journal.it/ @ Edizioni Labrys -- all rights reserved ISSN 2465-2415 No Longer, Not Yet: Retrofuture Hauntings on The Jetsons Stefano Morello The Graduate Center, City University of New York [email protected] From Back to the Future to The Wonder Years, from Peggy Sue Got Married to The Stray Cats’ records – 1980s youth culture abounds with what Michael D. Dwyer has called “pop nostalgia,” a set of critical affective responses to representations of previous eras used to remake the present or to imagine corrective alternatives to it. Longings for the Fifties, Dwyer observes, were especially key to America’s self-fashioning during the Reagan era (2015). Moving from these premises, I turn to anachronisms, aesthetic resonances, and intertextual references that point to, as Mark Fisher would have it, both a lost past and lost futures (Fisher 2014, 2-29) in the episodes of the Hanna-Barbera animated series The Jetsons produced for syndication between 1985 and 1987. A product of Cold War discourse and the early days of the Space Age, the series is characterized by a bidirectional rhetoric: if its setting emphasizes the empowering and alienating effects of technological advancement, its characters and its retrofuture aesthetics root the show in a recognizable and desirable all-American past. -

The Influence of Space Power Upon History (1944-1998)*

* The Influence of Space Power upon History (1944-1998) by Captain John Shaw, USAF * My interest in this subject grew during my experiences as an Air Force Intern 1997-98, working in both the Office of the Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Space, and in SAF/AQ, Space and Nuclear Deterrence Directorate. I owe thanks to Mr. Gil Klinger (acting DUSD(Space)) and BGen James Beale (SAF/AQS) for their advice and guidance during my internships. Thanks also to Mr. John Landon, Col Michael Mantz, Col James Warner, Lt Col Robert Fisher, and Lt Col David Spataro. Special thanks to Col Simon P. Worden for his insight on this topic. A primary task of the historian is to interpret events in the course of history through a unique lens, affording the scholar a new, and more intellectually useful, understanding of historical outcomes. This is precisely what Alfred Thayer Mahan achieved when he wrote his tour de force The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1660-1783). He interpreted the ebb and flow of national power in terms of naval power, and his conclusions on the necessity of sea control to guarantee national welfare led many governments of his time to expand their naval capabilities. When Mahan published his work in 1890, naval power had for centuries already been a central determinant of national military power.1 It remained so until joined, even eclipsed, by airpower in this century. Space, by contrast, was still the subject of extreme fiction a mere one hundred years ago, when Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and H.G. -

Area 51 and Gordon Coopers Confiscated Camera

Area 51 and Gordon Cooper's 'Confiscated Camera' By Jim Oberg Special to SPACE.com posted: 11:34 am ET 29 September 2000 http://www.space.com/sciencefiction/phenomena/cooper_questioned_000929.html Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper, in his new book Leap of Faith, presents a tale of government cover-ups related to spy cameras, to Area 51, and to similar subjects top-secret subjects, based on his own personal experiences on a NASA space mission. As a certified "American hero," his credibility with the public is impeccable. But several space veterans who SPACE.com consulted about one of Cooper's spaceflight stories had very different versions of the original events. And some of them showed me hard evidence to back up their skepticism. According to Cooper, in 1965 he carried a super-secret spy camera aboard Gemini-5 and accidentally got some shots of Area 51 in Nevada. Consequently, the camera and its film were confiscated by the Pentagon, never to be seen again. He was personally ordered by President Johnson not to divulge the film's contents. "One special mounted camera we carried had a huge telephoto lens," he wrote. "We were asked to shoot three specific targets from our spacecraft's window because the photo experts wanted to be able to measure the resolution of the pictures. "That's exactly what we did: Over Cuba, we took pictures of an airfield. Over the Pacific Ocean, we took pictures of ships at sea. Over a big U.S. city, we took pictures of cars in parking lots. Beyond that, we were encouraged to shoot away at other airfields, cities, and anything else we wanted along the way." In an exclusive interview with SPACE.com, NASA's former chief photo analyst, Richard Underwood, confirmed the existence of the experiment but remembered details about it in a very different way than Cooper did. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Highlights in Space 2010

International Astronautical Federation Committee on Space Research International Institute of Space Law 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren c/o CNES 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren UNITED NATIONS 75015 Paris, France 2 place Maurice Quentin 75015 Paris, France Tel: +33 1 45 67 42 60 Fax: +33 1 42 73 21 20 Tel. + 33 1 44 76 75 10 E-mail: : [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax. + 33 1 44 76 74 37 URL: www.iislweb.com OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS URL: www.iafastro.com E-mail: [email protected] URL : http://cosparhq.cnes.fr Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs is responsible for promoting international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space and assisting developing countries in using space science and technology. United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs P. O. Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26060-4950 Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5830 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.unoosa.org United Nations publication Printed in Austria USD 15 Sales No. E.11.I.3 ISBN 978-92-1-101236-1 ST/SPACE/57 *1180239* V.11-80239—January 2011—775 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS UNITED NATIONS OFFICE AT VIENNA Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law Progress in space science, technology and applications, international cooperation and space law UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 UniTEd NationS PUblication Sales no. -

GLONASS Spacecraft

INNO V AT IO N The task of designing and developing the GLONASS GLONASS spacecraft fell to the Scientific Production Association of Applied Mechan ics (Nauchno Proizvodstvennoe Ob"edinenie Spacecraft Prikladnoi Mekaniki or NPO PM) , located near Krasnoyarsk in Siberia. This major aero Nicholas L. Johnson space industrial complex was established in 1959 as a division of Sergei Korolev 's Kaman Sciences Corporation Expe1imental Design Bureau (Opytno Kon struktorskoe Byuro or OKB). (Korolev , among other notable achievements , led the Fourteen years after the launch of the effort to develop the Soviet Union's first first test spacecraft, the Russian Global Nav launch vehicle - the A launcher - which igation Satellite System (Global 'naya Navi placed Sputnik 1 into orbit.) The founding gatsionnaya Sputnikovaya Sistema or and current general director and chief GLONASS) program remains viable and designer is Mikhail Fyodorovich Reshetnev, essentially on schedule despite the economic one of only two still-active chief designers and political turmoil surrounding the final from Russia's fledgling 1950s-era space years of the Soviet Union and the emergence program. of the Commonwealth of Independent States A closed facility until the early 1990s, (CIS). By the summer of 1994, a total of 53 NPO PM has been responsible for all major GLONASS spacecraft had been successfully Russian operational communications, navi Despite the significant economic hardships deployed in nearly semisynchronous orbits; gation, and geodetic satellite systems to associated with the breakup of the Soviet Union of the 53 , nearly 12 had been normally oper date. Serial (or assembly-line) production of and the transition to a modern market economy, ational since the establishment of the Phase I some spacecraft, including Tsikada and Russia continues to develop its space programs, constellation in 1990. -

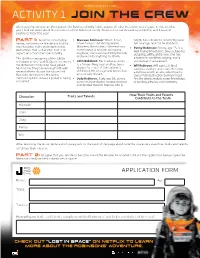

ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew

REPRODUCIBLE ACTIVITY ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew After crash-landing on an alien planet, the Robinson family fights against all odds to survive and escape. In this activity, you’ll find out more about the members of the Robinson family. Season 1 is now streaming on Netflix, and Season 2 premieres later this year. Part 1: Read the information • Maureen Robinson: Smart, brave, bright, has a desire to constantly prove below, and then use the details to fill in adventurous, and strong-willed, her courage, and can be stubborn. the character traits and talents table. Maureen, the mother, is the mission • Penny Robinson: Penny, age 15, is a Remember that a character trait is an commander. A brilliant aerospace well-trained mechanic. She is cheerful, aspect of a character’s personality. engineer, she loves her family fiercely outgoing, witty, and brave. She has and would do anything for them. The Netflix reimagining of the 1960s a talent for problem-solving, and is television series “Lost in Space” features • John Robinson: Her husband, John, somewhat of a daredevil. the Robinson family who have joined is a former Navy Seal and has been • Will Robinson: Will, age 11, is kind, Mission 24. They are leaving Earth with absent for much of the children’s cautious, creative, and smart. He forms several others aboard the spacecraft childhood. He is tough and smart, but a tight bond with an alien robot that he Resolute destined for the Alpha emotionally distant. saves from destruction during a forest Centauri system, where a planet is being • Judy Robinson: Judy, age 18, serves fire. -

Appendix a Apollo 15: “The Problem We Brought Back from the Moon”

Appendix A Apollo 15: “The Problem We Brought Back From the Moon” Postal Covers Carried on Apollo 151 Among the best known collectables from the Apollo Era are the covers flown onboard the Apollo 15 mission in 1971, mainly because of what the mission’s Lunar Module Pilot, Jim Irwin, called “the problem we brought back from the Moon.” [1] The crew of Apollo 15 carried out one of the most complete scientific explorations of the Moon and accomplished several firsts, including the first lunar roving vehicle that was operated on the Moon to extend the range of exploration. Some 81 kilograms (180 pounds) of lunar surface samples were returned for anal- ysis, and a battery of very productive lunar surface and orbital experiments were conducted, including the first EVA in deep space. [2] Yet the Apollo 15 crew are best remembered for carrying envelopes to the Moon, and the mission is remem- bered for the “great postal caper.” [3] As noted in Chapter 7, Apollo 15 was not the first mission to carry covers. Dozens were carried on each flight from Apollo 11 onwards (see Table 1 for the complete list) and, as Apollo 15 Commander Dave Scott recalled in his book, the whole business had probably been building since Mercury, through Gemini and into Apollo. [4] People had a fascination with objects that had been carried into space, and that became more and more popular – and valuable – as the programs progressed. Right from the start of the Mercury program, each astronaut had been allowed to carry a certain number of personal items onboard, with NASA’s permission, in 1 A first version of this material was issued as Apollo 15 Cover Scandal in Orbit No. -

Psychology of Space Exploration Psychology of About the Book Douglas A

About the Editor Contemporary Research in Historical Perspective Psychology of Space Exploration Psychology of About the Book Douglas A. Vakoch is a professor in the Department As we stand poised on the verge of a new era of of Clinical Psychology at the California Institute of spaceflight, we must rethink every element, including Integral Studies, as well as the director of Interstellar Space Exploration the human dimension. This book explores some of the Message Composition at the SETI Institute. Dr. Vakoch Contemporary Research in Historical Perspective contributions of psychology to yesterday’s great space is a licensed psychologist in the state of California, and Edited by Douglas A. Vakoch race, today’s orbiter and International Space Station mis- his psychological research, clinical, and teaching interests sions, and tomorrow’s journeys beyond Earth’s orbit. include topics in psychotherapy, ecopsychology, and meth- Early missions into space were typically brief, and crews odologies of psychological research. As a corresponding were small, often drawn from a single nation. As an member of the International Academy of Astronautics, intensely competitive space race has given way to inter- Dr. Vakoch chairs that organization’s Study Groups on national cooperation over the decades, the challenges of Interstellar Message Construction and Active SETI. communicating across cultural boundaries and dealing Through his membership in the International Institute with interpersonal conflicts have become increasingly of Space Law, he examines