Retrofuture Hauntings on the Jetsons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ll Be Your Huckleberry

I’ll Be Your Huckleberry It is amazing what will spark a memory. I was transferring a client’s film today and the Christmas scene that appeared on the screen was of a young boy who had just received an inflatable punching bag in the image of Huckleberry Hound. I had one of those. And I certainly remember Hanna-Barbera’s Huckleberry Hound being a favorite cartoon when I was growing up. But my memory played a trick on me. I would have sworn that the Huckleberry Hound Show that I watched as a youngster consisted of three segments: Huckleberry himself; Yogi Bear and Boo-Boo (whose segment eventually became more popular than those of the titular star); and (I thought) Quick Draw McGraw with his sidekick “bing bing bing” Ricochet Rabbit. But I was wrong. Quick Draw had his own show. The third segment for Huck, as he is familiarly known to his young fans, involved a pair of mice, Pixie and Dixie, and the object of their abuse, the cat Mr. Jinx. Just goes to show how memories can tend to distort and blend together over time. A few trivia tidbits about this cartoon from my past: Huckleberry Hound debuted in 1958 and featured a slow moving, slow talking blue dog who held a multitude of jobs and always seemed to succeed due to either luck or an obstinate persistence. Huck was voiced by Daws Butler who also provided the voices for Wally Gator, Yogi Bear, Quick Draw McGraw, and Snagglepuss. Daws Butler fashioned the voice of Yogi Bear after Art Carney’s portrayal of Ed Norton in The Honeymooners. -

Here Comes Television

September 1997 Vol. 2 No.6 HereHere ComesComes TelevisionTelevision FallFall TVTV PrPrevieweview France’France’ss ExpandingExpanding ChannelsChannels SIGGRAPHSIGGRAPH ReviewReview KorKorea’ea’ss BoomBoom DinnerDinner withwith MTV’MTV’ss AbbyAbby TTerkuhleerkuhle andand CTW’CTW’ss ArleneArlene SherShermanman Table of Contents September 1997 Vol. 2, . No. 6 4 Editor’s Notebook Aah, television, our old friend. What madness the power of a child with a remote control instills in us... 6 Letters: [email protected] TELEVISION 8 A Conversation With:Arlene Sherman and Abby Terkuhle Mo Willems hosts a conversation over dinner with CTW’s Arlene Sherman and MTV’s Abby Terkuhle. What does this unlikely duo have in common? More than you would think! 15 CTW and MTV: Shorts of Influence The impact that CTW and MTV has had on one another, the industry and beyond is the subject of Chris Robinson’s in-depth investigation. 21 Tooning in the Fall Season A new splash of fresh programming is soon to hit the airwaves. In this pivotal year of FCC rulings and vertical integration, let’s see what has been produced. 26 Saturday Morning Bonanza:The New Crop for the Kiddies The incurable, couch potato Martha Day decides what she’s going to watch on Saturday mornings in the U.S. 29 Mushrooms After the Rain: France’s Children’s Channels As a crop of new children’s channels springs up in France, Marie-Agnès Bruneau depicts the new play- ers, in both the satellite and cable arenas, during these tumultuous times. A fierce competition is about to begin... 33 The Korean Animation Explosion Milt Vallas reports on Korea’s growth from humble beginnings to big business. -

In This Episode of the Flintstones, the Main Characters Are Shown to Seek Martial Arts Lessons

In this episode of the Flintstones, the main characters are shown to seek martial arts lessons. The judo master in the scene is depicted as a Japanese man who wears a sinister-looking smile throughout the scene. He offers the characters lessons at supposedly good prices. As he rattles off the offers by ensuring them that they could get "silver medal lessons" for "[a] big bargain, big bargain" and "for a few more measly dollars ... gold medals, diamond medals...," his pronunciations are exaggeratedly shown to be wrong by a mix up between r's and l's and by an obvious difference in the emphasis on syllables. The man's speech is set apart from the other characters' by juxtaposing his differently accented words to the others' SAE pronunciation. Also, the Flintstones and their friends bowed while imitating his accent as if attempting to fit that man's mannerisms. However, this can be seen as making light of the man's characteristics and manners as if they are silly. In this scene, the judo master portrays prevalent stereotypes about Asians. The man's inability to enunciate r's and l's reflect the struggle that many people face in differentiating between r's and l's in English because their native tongues do not make the same distinction. More importantly, the judo master's speech is used to indicate a lack of intelligence, as evidence by Fred's comment, "What does 'et cetera, et cetera' mean in Japanese? Sucker?" which is followed by Barney's response in a tone mocking the Japanese man's, "Oh, that's for sure!" Furthermore, prior to that, Fred had thrown in an unintelligible word in an attempt to imitate the man's Japanese accent. -

Chapter Fourteen Men Into Space: the Space Race and Entertainment Television Margaret A. Weitekamp

CHAPTER FOURTEEN MEN INTO SPACE: THE SPACE RACE AND ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION MARGARET A. WEITEKAMP The origins of the Cold War space race were not only political and technological, but also cultural.1 On American television, the drama, Men into Space (CBS, 1959-60), illustrated one way that entertainment television shaped the United States’ entry into the Cold War space race in the 1950s. By examining the program’s relationship to previous space operas and spaceflight advocacy, a close reading of the 38 episodes reveals how gender roles, the dangers of spaceflight, and the realities of the Moon as a place were depicted. By doing so, this article seeks to build upon and develop the recent scholarly investigations into cultural aspects of the Cold War. The space age began with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. But the space race that followed was not a foregone conclusion. When examining the United States, scholars have examined all of the factors that led to the space technology competition that emerged.2 Notably, Howard McCurdy has argued in Space and the American Imagination (1997) that proponents of human spaceflight 1 Notably, Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rocket’s Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957, Cambridge Centennial of Flight (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) offers the first history of the social and cultural contexts of Soviet science and the military rocket program. Alexander C. T. Geppert, ed., Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) resulted from a conference examining the intersections of the social, cultural, and political histories of spaceflight in the Western European context. -

The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Richard Hills a Smith Script

THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME BY RICHARD HILLS A SMITH SCRIPT EXTRACT This script is protected by copyright laws. No performance of this script – IN ANY MEDIA – may be undertaken without payment of the appropriate fee and obtaining a licence. For further information, please contact SMITH SCRIPTS – [email protected] THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME A Pantomime By RICHARD HILLS Loosely based on the story by Victor Hugo CHARACTERS 1ST Gargoyle Part of Bell Tower 2nd Gargoyle Part of Bell Tower Claude Frollo Nasty Minister of Justice. Qussimodo The Hunchback of Notre Dame Fe Fe La Large Proprietress of the Jolly Frenchman Gringoire A Street Actor Yvette Owner of Ye Olde Bread Basket Shop Clopin King of the Beggars Esmeralda A Gypsy Dancer Marguerite Daughter of Fe Fe Phoebus Captain of the Guard Chorus of Street Urchins, Carnival Revellers, Townspeople, Beggars, Soldiers and Dancers SYNOPSIS OF SCENES PROLOGUE Part of the Bell Tower of Notre Dame ACT 1 Scene 1 The Square outside Notre Dame Scene 2 Part of the Bell Tower of Notre Dame Scene 3 The Square outside Notre Dame, the next morning Scene 4 Part of the Bell Tower of Notre Dame Scene 5 The Court of Miracles, that night ACT 2 Scene 1 The Square outside Notre Dame, next morning Scene 2 Part of the Bell Tower of Notre Dame, later that day Scene 3 The Square outside Notre Dame, later that day Scene 4 Another street in Paris, the next day Scene 5 The weddings inside Notre Dame MUSICAL NUMBERS This is a list of suggested songs only, and can be changed to suit needs and voices available. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Teachers Guide

Teachers Guide Exhibit partially funded by: and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. TEACHERS GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE 3 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW 4 CORRELATION TO EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS 9 EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS CHARTS 11 EXHIBIT EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES 13 BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR TEACHERS 15 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 23 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES • BUILD YOUR OWN ZOETROPE 26 • PLAN OF ACTION 33 • SEEING SPOTS 36 • FOOLING THE BRAIN 43 ACTIVE LEARNING LOG • WITH ANSWERS 51 • WITHOUT ANSWERS 55 GLOSSARY 58 BIBLIOGRAPHY 59 This guide was developed at OMSI in conjunction with Animation, an OMSI exhibit. 2006 Oregon Museum of Science and Industry Animation was developed by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in collaboration with Cartoon Network and partially funded by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation. and 2006 Cartoon Network. All rights reserved. Animation Teachers Guide 2 © OMSI 2006 HOW TO USE THIS TEACHER’S GUIDE The Teacher’s Guide to Animation has been written for teachers bringing students to see the Animation exhibit. These materials have been developed as a resource for the educator to use in the classroom before and after the museum visit, and to enhance the visit itself. There is background information, several classroom activities, and the Active Learning Log – an open-ended worksheet students can fill out while exploring the exhibit. Animation web site: The exhibit website, www.omsi.edu/visit/featured/animationsite/index.cfm, features the Animation Teacher’s Guide, online activities, and additional resources. Animation Teachers Guide 3 © OMSI 2006 EXHIBIT OVERVIEW Animation is a 6,000 square-foot, highly interactive traveling exhibition that brings together art, math, science and technology by exploring the exciting world of animation. -

Zoom on the Fly!

How to Zoom on the Fly! Let’s say you are in Chat and you realize it will be much easier if you show the student your screen or see theirs. Here’s how to set up an instant Zoom meeting. 1. Set up a Zoom account via CCC Confer. Visit www.conferzoom.org and set up an account using your Cerritos.edu email address. (You only need one account for the entire CA Community College System, so if you already have one from another school you can use that one and you don’t need to set up an account.) 2. Create an On-the-Fly session. Visit https://cccconfer.zoom.us/ Click Host A Meeting. You can decide to host With Video On if you want the other people. If you choose With Video Off you will still be able to share the screen. (If it asks you to login first just put in your credentials from CCC Confer. HOST A MEETING ..., MY ACCOUNT With Video Off With Video On Click Open Link to launch the application. • Launch Application This Ii k needs to be ope ed wit h an application. Send to: 0 Remember my c oice for zoom mtg links. Cancel Open link j 1 Indicate how you want to set up the audio for yourself. • Choose ONE of the audio conference options Phone Call Computer Audio Join With Computer Audio Test Speaker and Microphone 0 Automatically join audio by computer when joining a meeting If you chose to conduct the meeting without video you will see this screen: Meeting Topic: Stephanie Rosenblatt's Zoom Meeting Host Name: Stephanie Rosenblatt Invitation URL: https://cccconfer.zoom.us/j/349926273 Copy URL ◄◄---- Participant ID: 41 Join Audio Share Scree n Invite Others Computer Audio Connected Copy the URL and send it to the student in chat so they can join, then click Share Screen. -

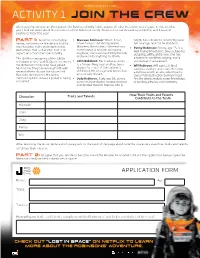

ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew

REPRODUCIBLE ACTIVITY ACTIVITY 1 Join the Crew After crash-landing on an alien planet, the Robinson family fights against all odds to survive and escape. In this activity, you’ll find out more about the members of the Robinson family. Season 1 is now streaming on Netflix, and Season 2 premieres later this year. Part 1: Read the information • Maureen Robinson: Smart, brave, bright, has a desire to constantly prove below, and then use the details to fill in adventurous, and strong-willed, her courage, and can be stubborn. the character traits and talents table. Maureen, the mother, is the mission • Penny Robinson: Penny, age 15, is a Remember that a character trait is an commander. A brilliant aerospace well-trained mechanic. She is cheerful, aspect of a character’s personality. engineer, she loves her family fiercely outgoing, witty, and brave. She has and would do anything for them. The Netflix reimagining of the 1960s a talent for problem-solving, and is television series “Lost in Space” features • John Robinson: Her husband, John, somewhat of a daredevil. the Robinson family who have joined is a former Navy Seal and has been • Will Robinson: Will, age 11, is kind, Mission 24. They are leaving Earth with absent for much of the children’s cautious, creative, and smart. He forms several others aboard the spacecraft childhood. He is tough and smart, but a tight bond with an alien robot that he Resolute destined for the Alpha emotionally distant. saves from destruction during a forest Centauri system, where a planet is being • Judy Robinson: Judy, age 18, serves fire. -

Desire, Disease, Death, and David Cronenberg: the Operatic Anxieties of the Fly

Desire, Disease, Death, and David Cronenberg: The Operatic Anxieties of The Fly Yves Saint-Cyr 451 University of Toronto Introduction In 1996, Linda and Michael Hutcheon released their groundbreaking book, Opera: Desire, Disease, Death, a work that analyses operatic representations of tuberculosis, syphilis, cholera, and AIDS. They followed this up in 2000 with Bodily Charm, a discussion of the corporeal in opera; and, in 2004, they published Opera: The Art of Dying, in which they argue that opera has historically provided a metaphorical space for the ritualistic contemplation of mortality, whether the effect is cathartic, medita- tive, spiritual, or therapeutic. This paper is based on a Hutcheonite reading of the Fly saga, which to date is made up of seven distinct incarnations: George Langelaan published the original short story in 1957; Neumann and Clavell’s 1958 film adaptation was followed by two sequels in 1959 and 1965; David Cronenberg re-made the Neumann film in 1986, which gener- ated yet another sequel in 1989; and, most recently in 2008, Howard Shore and David Henry Hwang adapted Cronenberg’s film into an opera. If the Hutcheons are correct that opera engenders a ritualistic contemplation of mortality by sexualising disease, how does this practice influence composers and librettists’ choice of source material? Historically, opera has drawn on the anxieties of its time and, congruently, The Fly: Canadian Review of Comparative Literature / Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée CRCL DECEMBER 2011 DÉCEMBRE RCLC 0319–051x/11/38.4/451 © Canadian Comparative Literature Association CRCL DECEMBER 2011 DÉCEMBRE RCLC The Opera draws on distinctly 21st-century fears. -

Available Videos for TRADE (Nothing Is for Sale!!) 1

Available Videos For TRADE (nothing is for sale!!) 1/2022 MOSTLY GAME SHOWS AND SITCOMS - VHS or DVD - SEE MY “WANT LIST” AFTER MY “HAVE LIST.” W/ O/C means With Original Commercials NEW EMAIL ADDRESS – [email protected] For an autographed copy of my book above, order through me at [email protected]. 1966 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS and NBC Fall Schedule Preview 1997 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS Fall Schedule Preview (not for trade) Many 60's Show Promos, mostly ABC Also, lots of Rock n Roll movies-“ROCK ROCK ROCK,” “MR. ROCK AND ROLL,” “GO JOHNNY GO,” “LET’S ROCK,” “DON’T KNOCK THE TWIST,” and more. **I ALSO COLLECT OLD 45RPM RECORDS. GOT ANY FROM THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES?** TV GUIDES & TV SITCOM COMIC BOOKS. SEE LIST OF SITCOM/TV COMIC BOOKS AT END AFTER WANT LIST. Always seeking “Dick Van Dyke Show” comic books and 1950s TV Guides. Many more. “A” ABBOTT & COSTELLO SHOW (several) (Cartoons, too) ABOUT FACES (w/o/c, Tom Kennedy, no close - that’s the SHOW with no close - Tom Kennedy, thankfully has clothes. Also 1 w/ Ben Alexander w/o/c.) ACADEMY AWARDS 1974 (***not for trade***) ACCIDENTAL FAMILY (“Making of A Vegetarian” & “Halloween’s On Us”) ACE CRAWFORD PRIVATE EYE (2 eps) ACTION FAMILY (pilot) ADAM’S RIB (2 eps - short-lived Blythe Danner/Ken Howard sitcom pilot – “Illegal Aid” and rare 4th episode “Separate Vacations” – for want list items only***) ADAM-12 (Pilot) ADDAMS FAMILY (1ST Episode, others, 2 w/o/c, DVD box set) ADVENTURE ISLAND (Aussie kid’s show) ADVENTURER ADVENTURES IN PARADISE (“Castaways”) ADVENTURES OF DANNY DEE (Kid’s Show, 30 minutes) ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY (8 Episodes, 4 w/o/c “Lapidary Wheel” “Gibraltar Toad,”“ Morocco,” “Homing Pigeon,” Others without commercials - “Sea Cucumber,” “Hawaiian Hamza,” “Dancing Mouse,” & “Wrong Rembrandt”) ADVENTURES OF LUCKY PUP 1950(rare kid’s show-puppets, 15 mins) ADVENTURES OF A MODEL (Joanne Dru 1956 Desilu pilot. -

A Dpics-Ii Analysis of Parent-Child Interactions

WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this dissertation is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This dissertation does not include proprietary or classified information. _______________________ Lori Jean Klinger Certificate of Approval: ________________________ ________________________ Steven K. Shapiro Elizabeth V. Brestan, Chair Associate Professor Associate Professor Psychology Psychology ________________________ ________________________ James F. McCoy Elaina M. Frieda Associate Professor Assistant Professor Psychology Experimental Psychology _________________________ Joe F. Pittman Interim Dean Graduate School WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Lori Jean Klinger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 15, 2006 WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Lori Jean Klinger Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this dissertation at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. ________________________ Signature of Author ________________________ Date of Graduation iii VITA Lori Jean Klinger, daughter of Chester Klinger and JoAnn (Fetterolf) Bachrach, was born October 24, 1965, in Ashland, Pennsylvania. She graduated from Owen J. Roberts High School as Valedictorian in 1984. She graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1988 and served as a Military Police Officer in the United States Army until 1992.