Appendix a Apollo 15: “The Problem We Brought Back from the Moon”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Worksheets, Assessments, and Answer Keys

Apollo Mission Worksheet Team Names _________________________ Your team has been assigned Apollo Mission _______ Color _________________ 1. Go to google.com/moon and find your mission, click on it and then zoom in. 2. Find # 1, this will give you information to answer the questions below. 3. On your moon map, find the location of the mission landing site and locate this spot on your map. Choose a symbol and the correct color for your mission (each mission has a specific symbol and you can use this if you like or make up your own). In the legend area put your symbol and mission number. 4. Who were the astronauts on the mission? The astronauts on the mission were ______________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ 5. When did the mission take place? The mission took place from _______________________________________________ 6. How many days did the mission last? The mission lasted ______________________________________________________ 7. Where did the mission land? The mission landed at____________________________________________________ 8. Why did the mission land here? They landed at this location because ________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 9. What was the goal of the mission? The goal of the mission was_______________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ -

Manual of Philatelic Judging

Revised March 26, 2010 — (23A added, & 33 Rules cleaned up) American Philatelic Society Manual of Philatelic Judging Sixth Edition C O N T E N T S Foreword to the Sixth Edition 3 1 Introduction to the Sixth Edition 5 2 Judging Criteria 6 3 Judging Criteria Explained 10 4 Using the Uniform Exhibit Evaluation Form 20 5 Title Page and Synopsis 23 Exhibit Classes and Divisions General Class: Postal Division 6 Traditional 25 7 Postal History 28 8 Aerophilately 32 9 Astrophilately 37 10 Postal Stationery 39 11 First Day Cover Exhibits in the Postal Division 42 General Class: Revenue Division 12 Traditional Revenue 45 13 Fiscal History 48 General Class: Illustrated Mail Division 14 Cacheted First Day Covers 51 15 Advertising, Patriotic and Event Cover 53 16 Maximaphily 55 17 General Class: Display Division 57 18 General Class: Cinderella Division 59 19 General Class: Thematic Division 62 1 20 Special Studies 66 21 Picture Postcard Class 67 22 One Frame Class 69 23 Youth Class 70 23A Literature Class 73 Judging 24 The Ethics of Judging 77 25 Judging Apprenticeship Program 79 26 Qualifications for Judges 84 27 Judging Procedures 85 28 Chief Judge 90 29 Judging Exhibits at Local and Regional Shows 96 30 Judging in Canada 97 31 International Judging 100 APS 32 CANEJ 103 33 Rules for WSP Shows 104 34 Glossary of Terms Used in Philatelic Exhibit Evaluation 115 * * * * * 2 Foreword to the Sixth Edition Since the publication of the APS Manual of Philatelic Judging, Fifth Edition in 2002, numerous changes have been made in the way exhibits are judged and new exhibiting classes have been recognized. -

In Memory of Astronaut Michael Collins Photo Credit

Gemini & Apollo Astronaut, BGEN, USAF, Ret, Test Pilot, and Author Dies at 90 The Astronaut Scholarship Foundation (ASF) is saddened to report the loss of space man Michael Collins BGEN, USAF, Ret., and NASA astronaut who has passed away on April 28, 2021 at the age of 90; he was predeceased by his wife of 56 years, Pat and his son Michael and is survived by their daughters Kate and Ann and many grandchildren. Collins is best known for being one of the crew of Apollo 11, the first manned mission to land humans on the moon. Michael Collins was born in Rome, Italy on October 31, 1930. In 1952 he graduated from West Point (same class as future fellow astronaut, Ed White) with a Bachelor of Science Degree. He joined the U.S. Air Force and was assigned to the 21st Fighter-Bomber Wing at George AFB in California. He subsequently moved to Europe when they relocated to Chaumont-Semoutiers AFB in France. Once during a test flight, he was forced to eject from an F-86 after a fire started behind the cockpit; he was safely rescued and returned to Chaumont. He was accepted into the USAF Experimental Flight Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California. In 1960 he became a member of Class 60C which included future astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Irwin, and Tom Stafford. His inspiration to become an astronaut was the Mercury Atlas 6 flight of John Glenn and with this inspiration, he applied to NASA. In 1963 he was selected in the third group of NASA astronauts. -

PEANUTS and SPACE FOUNDATION Apollo and Beyond

Reproducible Master PEANUTS and SPACE FOUNDATION Apollo and Beyond GRADE 4 – 5 OBJECTIVES PAGE 1 Students will: ö Read Snoopy, First Beagle on the Moon! and Shoot for the Moon, Snoopy! ö Learn facts about the Apollo Moon missions. ö Use this information to complete a fill-in-the-blank fact worksheet. ö Create mission objectives for a brand new mission to the moon. SUGGESTED GRADE LEVELS 4 – 5 SUBJECT AREAS Space Science, History TIMELINE 30 – 45 minutes NEXT GENERATION SCIENCE STANDARDS ö 5-ESS1 ESS1.B Earth and the Solar System ö 3-5-ETS1 ETS1.B Developing Possible Solutions 21st CENTURY ESSENTIAL SKILLS Collaboration and Teamwork, Communication, Information Literacy, Flexibility, Leadership, Initiative, Organizing Concepts, Obtaining/Evaluating/Communicating Ideas BACKGROUND ö According to NASA.gov, NASA has proudly shared an association with Charles M. Schulz and his American icon Snoopy since Apollo missions began in the 1960s. Schulz created comic strips depicting Snoopy on the Moon, capturing public excitement about America’s achievements in space. In May 1969, Apollo 10 astronauts traveled to the Moon for a final trial run before the lunar landings took place on later missions. Because that mission required the lunar module to skim within 50,000 feet of the Moon’s surface and “snoop around” to determine the landing site for Apollo 11, the crew named the lunar module Snoopy. The command module was named Charlie Brown, after Snoopy’s loyal owner. These books are a united effort between Peanuts Worldwide, NASA and Simon & Schuster to generate interest in space among today’s younger children. -

Application Form

United Nations Expo 2021 Philatelic Exhibition Entry Form American Philatelic Center, Bellefonte, PA October 29-30, 2021 DEADLINE: September 3, 2021 - Please print or type. Name: ______________________________________________________ Phone: _____________________________________ E-Mail: _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address: ________________________________________________________________________________________________ City: __________________________________________ State: ________________ Postal Code: ________________________ Country: ________________________________________________________________________________________________ UNPI Member: □Yes □No UNPI Number _____________ APS Member: □Yes □No APS Number: _______________ Other Philatelic Memberships: _______________________________________________________________________________ If youth, date of birth (see Prospectus rule #3): __________________________________________________________________ Title of Exhibit: ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Description (20 words or less): _______________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Number of Frames: ___________ Number of Pages: ___________ Page size(s): _______________________________________ -

A Comparative Analysis of the Geology Tools Used During the Apollo Lunar Program and Their Suitability for Future Missions to the Om on Lindsay Kathleen Anderson

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2016 A Comparative Analysis Of The Geology Tools Used During The Apollo Lunar Program And Their Suitability For Future Missions To The oM on Lindsay Kathleen Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Anderson, Lindsay Kathleen, "A Comparative Analysis Of The Geology Tools Used During The Apollo Lunar Program And Their Suitability For Future Missions To The oonM " (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1860. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1860 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GEOLOGY TOOLS USED DURING THE APOLLO LUNAR PROGRAM AND THEIR SUITABILITY FOR FUTURE MISSIONS TO THE MOON by Lindsay Kathleen Anderson Bachelor of Science, University of North Dakota, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Grand Forks, North Dakota May 2016 Copyright 2016 Lindsay Anderson ii iii PERMISSION Title A Comparative Analysis of the Geology Tools Used During the Apollo Lunar Program and Their Suitability for Future Missions to the Moon Department Space Studies Degree Master of Science In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. -

Airpost Journal — ARTICLES — Letters to When “FAM-18” Is Not Enough

AAIIRRPPOOSSTT JJOOUURRNNAALL The Official Publication of the American Air Mail Society January 2015 Volume 86, No. 1 Whole No. 1015 January’s Featured Article — When “Fam-1P8ag”e 1i3 s Not Enough Zeppelins & Aerophilately Ask for our Free Price List of Worldwide Flight covers and stamps. The following is a small sampling – full list on Website! United States 1934 Catapult 557, 698 (2) catapult to Berlin then forwarded Bremen to Aden! . $750.00 1938 C23c ultramarine and carmine, with PF Cert. Rare!. $2,750.00 Germany / Luxembourg Bremen Catapult (K59 LX $1500) . $1,000.00 Saar 1953(May 3) 1st Balloon Post of Saar, "Henri Dunant" of the Haagsche Balloon Club in Holland. FDC, special cancel, addressed to NY. VF card with Scott B95. $45.00 Senegal 1933 6th South America Flight sent to Brazil S.229Aa . $1,850.00 Somali Coast 1933 4th South America Flight sent to Brazil S.223 . $1,850.00 Spanish Andorra 1930 Pan Am flight s.64XVa signed . $2,000.00 Sweden 1919 S.19I "Bodensee" card on board with Zeppelin message with certificate. $3,750.00 Switzerland 1930 (May 29) Catapult cover, legal sized, to Boston. 2¢ US Bremen postal stationery with 3¢ violet Tell's son large block of 32 + 2 others. Sent from Basel. 18 mailed. K255 SZ cv . $500.00 Tanganyika 1934 10th South America Flight via London and sent to Brazil S.280Aa . $1,500.00 Henry Gitner Philatelists, Inc. PO Box 3077T, Middletown NY 10940 Email: [email protected] — http://www.hgitner.com JANUARY 2015 PAGE 1 In This Issue of the Airpost Journal — ARTICLES — Letters to When “FAM-18” is Not Enough .................................................................... -

Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 6-2013 The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress Andrew Follett College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Follett, Andrew, "The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 584. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/584 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wrong Right Stuff: Why NASA Consistently Fails at Congress A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in Government from The College of William and Mary by Andrew Follett Accepted for . John Gilmour, Director . Sophia Hart . Rowan Lockwood Williamsburg, VA May 3, 2013 1 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements 3 Part 1: Introduction and Background 4 Pre Soviet Collapse: Early American Failures in Space 13 Pre Soviet Collapse: The Successful Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo Programs 17 Pre Soviet Collapse: The Quasi-Successful Shuttle Program 22 Part 2: The Thin Years, Repeated Failure in NASA in the Post-Soviet Era 27 The Failure of the Space Exploration Initiative 28 The Failed Vision for Space Exploration 30 The Success of Unmanned Space Flight 32 Part 3: Why NASA Fails 37 Part 4: Putting this to the Test 87 Part 5: Changing the Method. -

Apollo 14 Press

NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION WO 2-4155 WASHINGT0N.D.C. 20546 lELS.wo 36925 RELEASE NO: 71-3K FOR RELEASE: THURSDAY A. M . January 21, 1971 P R E S S K I T -more - 1/11/71 2 -0- NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION (m2) 962-4155 N E w s WASHINGTON,D.C. 20546 mu: (202) 963-6925 FOR RELEASE: THURSDAY A..M. January 21:, 1971 RELEASE NO: 71-3 APOLLO 14 LAUNCH JAN. 31 Apollo 14, the sixth United States manned flight to the Moon and fourth Apollo mission with an objective of landing men on the Moon, is scheduled for launch Jan. 31 at 3:23 p.m. EST from Kennedy Space Center, Fla. The Apollo 14 lunar module is to land in the hilly upland region north of the Fra Mauro crater for a stay of about 33 hours, during whick, the landing crew will leave the spacecraft twice to set up scientific experiments on the lunar surface and to continue geological explorations. The two earlier Apollo lunar landings were Apollo 11 at Tranquillity Base and Apollo 12 at Surveyor 3 crater in the Ocean of Storms. Apollo 14 prime crewmen are Spacecraft Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr., Command Module Pilot Stuart A. Roosa, and Lunar Module Pilot Edgar I). Mitchell. Shepard is a Navy car-sain Roosa an Air Force major and Mitchell a Navy commander. -more- 1/8/71 -2- Lunar materials brought- back from the Fra Mauro formation are expected to yield information on the early history of the Moon, the Earth and the solar system--perhaps as long ago as five billion years. -

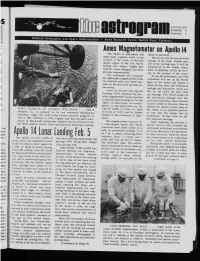

Apollo 14 Lunar Landing Feb. 5

,$ VOLUME XIII NUMBER 8 February 4 National Aeronaulics and Sp :e Administration ,, Ames Research Center. Moffeft Field. California AmesMagnetometer on Apollo 14 The Apollo 14 astronauts will hours of operation. chart local magneticfields on the The devicewill be carriedon the surface of the moon, in the hilly outside of the Lunar Module near upland region of the Fra Mauro one of the landinglegs. It will be landing site, using a highly spe- transferredto the Mobile Equip- cialized,Ames designedand built, meat Transporter (MET) for mov- portablemagnetometer. ing on the surface of the moon. The astronautswill transport To use the instrument,one of the the lightweightmagnetometer on the astronautswill set up the sensor two-wheeledpush cart which car- head on the tripod and deploy it ries all the mission’sportable ex- about 40 feet from the electronics periments. package and indicators,which are Ames’ Dr. Palmer Dyal, Special left on the MET. He then calls ProjectsOffice, proposed the por- out readings from three meters on table magnetometerexperimentand the electronicspackage over the is the principalinvestigator for the voice communicationlink to Mission Apollo 14 experiment.Co-investi- ControlCenter at Houston.Then he gators on the experiment are Dr. rotates the cubical sensor head on FIRST AMERICAN TO JOURNEY INTO SPACE . Al.an B. Charles Sonett of Ames, Dr. Gene the tripodto an oppositeposition Shepard, Jr., is pictured as he was recovered following his Simmons of M.S.C. and Dr. Robert to fine tune the sensor and its suborbitalflight, the first in the Project Mercury program,on DuBois of the Universityof Okla- electronics.Be then calls out the May 5, t961. -

Go for Lunar Landing Conference Report

CONFERENCE REPORT Sponsored by: REPORT OF THE GO FOR LUNAR LANDING: FROM TERMINAL DESCENT TO TOUCHDOWN CONFERENCE March 4-5, 2008 Fiesta Inn, Tempe, AZ Sponsors: Arizona State University Lunar and Planetary Institute University of Arizona Report Editors: William Gregory Wayne Ottinger Mark Robinson Harrison Schmitt Samuel J. Lawrence, Executive Editor Organizing Committee: William Gregory, Co-Chair, Honeywell International Wayne Ottinger, Co-Chair, NASA and Bell Aerosystems, retired Roberto Fufaro, University of Arizona Kip Hodges, Arizona State University Samuel J. Lawrence, Arizona State University Wendell Mendell, NASA Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Clive Neal, University of Notre Dame Charles Oman, Massachusetts Institute of Technology James Rice, Arizona State University Mark Robinson, Arizona State University Cindy Ryan, Arizona State University Harrison H. Schmitt, NASA, retired Rick Shangraw, Arizona State University Camelia Skiba, Arizona State University Nicolé A. Staab, Arizona State University i Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................2 Notes...............................................................................................................................3 THE APOLLO EXPERIENCE............................................................................................4 Panelists...........................................................................................................................4 -

Stereo Reconstruction from Apollo 15 and 16 Metric Camerazachary

42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2011) 2267.pdf Stereo Reconstruction from Apollo 15 and 16 Metric Camera Zachary Moratto1, Ara Nefian1,2, Taemin Kim1, Michael Broxton1,2, Ross Beyer1,3, and Terry Fong1, 1NASA Ames Research Center, MS 269-3, Moffett Field, CA, USA ([email protected]), 2Carnegie Mellon University, 3Carl Sagan Center SETI Introduction saic, DIM, and precision maps are produced for both This paper presents the production of digital terrain mod- missions separately. els (DTMs) and digital image mosaics (DIMs) of the Lu- The DTM mosaic is formed by a weighted average of nar surface that cover a large portion of the near-side of the stereo pair DTMs. Input DTMs were weighted max- the Moon at 40 m/px and 10 m/px respectively. These imum value at their centers and then feathered to zero at data products, produced under direction of the NASA the edges. The DTM mosaics are shown in Fig. 1 and 2. ESMD Lunar Mapping and Modeling Project (LMMP), The DIM was created by projecting the original res- are based on 2600 stereo image pairs from the Apollo olution images onto the 40 m/px DTMs, creating indi- 15 and 16 missions that were digitized at high resolution vidual orthoimages. Those orthoimages were then mo- from the original mission films [1]. Our reconstruction saicked by a process described in [5] without reflectance. was carried out using the highly automated Ames Stereo Therefore, only the final image mosaic and time expo- Pipeline software [2], which runs on NASA’s Pleiades sures were calculated.