Consultation on the Potential for Increased On-Rail Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Study: Deutsche Bahn AG 2

Case Study : Deutsche Bahn AG Deutsche Bahn on the Fast Track to Fight Co rruption Case Study: Deutsche Bahn AG 2 Authors: Katja Geißler, Hertie School of Governance Florin Nita, Hertie School of Governance This case study was written at the Hertie School of Governanc e for students of public po licy Case Study: Deutsche Bahn AG 3 Case Study: Deutsche Bahn AG Deutsche Bahn on the Fast Track to Fight Corru ption Kontakt: Anna Peters Projektmanager Gesellschaftliche Verantwortung von Unternehmen/Corporate Soc ial Responsibility Bertelsmann Stiftung Telefon 05241 81 -81 401 Fax 05241 81 -681 246 E-Mail anna .peters @bertelsmann.de Case Study: Deutsche Bahn AG 4 Inhalt Ex ecu tive Summary ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 5 Deutsche Bahn AG and its Corporate History ................................ ............................... 6 A New Manager in DB ................................ ................................ ................................ .. 7 DB’s Successful Take Off ................................ ................................ ............................. 8 How the Corruption Scandal Came all About ................................ ................................ 9 Role of Civil Society: Transparency International ................................ ........................ 11 Cooperation between Transparency International and Deutsche Bahn AG .................. 12 What is Corruption? ................................ ................................ ............................... -

Can Competition for and in the Market Co-Exist in Terms of Delivering Cost Efficient Services? Evidence from Open Access Train O

Transportation Research Part A 113 (2018) 114–124 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Transportation Research Part A journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tra Can competition for and in the market co-exist in terms of delivering cost efficient services? Evidence from open access train T operators and their franchised counterparts in Britain ⁎ Phill Wheata, , Andrew S.J. Smitha, Torris Rasmussenb a Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds, UK b Norwegian Railway Directorate, Norway ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This paper aims to inform an important policy debate in Europe on how best to open up pas- Returns to density senger rail markets to increased competition: and specifically, whether to allow open access train Competition-in-the-market operators alongside franchised (tendered) operators. The paper utilises new British data to Competition-for-the-market analyse the cost side of this debate. Our data is unique in that we have cost data by route level for both the incumbent (corresponding to British franchises) and the open access operators, as op- posed to only having cost data on the incumbent at the network level as in other countries. The open access operators are found to have comparable unit costs to franchised operators. This is unexpected considering the significant returns to density that benefit the larger franchised op- erators. This is subsequently found to be due to lower input prices and an ‘open access business model’ effect that outweigh any density disadvantages. Overall we find that there are negligible cost disadvantages of allowing open access operators to compete with franchised intercity op- erators. -

Leeds Thesis Template

Understanding the Relationship Between Capacity Utilisation and Performance and the Implications for the Pricing of Congested Rail Networks John Alexander Haith Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute for Transport Studies February, 2015 - ii - The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own, except where work which has formed part of jointly-authored publications has been included. The contribution of the candidate and the other authors to this work has been explicitly indicated below. The candidate confirms that appropriate credit has been given within the thesis where reference has been made to the work of others. Elements of the work contained in this thesis have previously appeared in the published paper:- Haith, J., Johnson, D. and Nash, C. 2014.The Case for Space: the Measurement of Capacity Utilisation, its Relationship with Reactionary Delay and the Calculation of the Capacity Charge for the British Rail Network. Transportation Planning and Technology 37 (1) February 2014 Special Issue: Universities’ Transport Study Group UK Annual Conference 2013. Where there is specific use of the contents of the above paper in this thesis reference is made to it in the appropriate part of the text. However, general use of the work contained in the paper is particularly made in Chapter 5 (Methodology), Chapter 6 (The Data Set) and Chapter 7 (Results). It should also be noted that all research and analysis contained in this thesis (and the paper) was conducted by the candidate. Secondly, substantial additional analysis was conducted between the finalisation of the paper and the writing of this thesis meaning that the results of the research have expanded significantly. -

Competition Figures

2017 Competition figures Publishing details Deutsche Bahn AG Economic, Political & Regulatory Affairs Potsdamer Platz 2 10785 Berlin No liability for errors or omissions Last modified: May 2018 www.deutschebahn.com/en/group/ competition year's level. For DB's rail network, the result of these trends was a slight 0.5% increase in operating performance. The numerous competitors, who are now well established in the market, once again accounted for a considerable share of this. Forecasts anticipate a further increase in traffic over the coming years. To accommodate this growth while making a substantial contribution to saving the environment and protecting the climate, DB is investing heavily in a Dear readers, modernised and digitalised rail net- work. Combined with the rail pact that The strong economic growth in 2017 we are working toward with the Federal gave transport markets in Germany and Government, this will create a positive Europe a successful year, with excellent competitive environment for the rail- performance in passenger and freight ways so that they can help tackle the sectors alike. Rail was the fastest- transport volumes of tomorrow with growing mode of passenger transport high-capacity, energy-efficient, in Germany. Rising passenger numbers high-quality services. in regional, local and long distance transport led to substantial growth in Sincerely, transport volume. In the freight mar- ket, meanwhile, only road haulage was able to capitalise on rising demand. Among rail freight companies, the volume sold remained at the -

Bestellschein DB Job-Ticket Bitte Vollständig, Gut Lesbar in Großbuchstaben Ausfüllen

Das DB Job-Ticket jetzt auch als Handy-Ticket Bestellschein DB Job-Ticket Bitte vollständig, gut lesbar in Großbuchstaben ausfüllen. Ihre Unterschrift nicht vergessen! Neubestellung als Handy-Ticket Gültigkeitsbeginn: (Angebot beinhaltet keine BahnCard 25) 0 1 2 0 Neubestellung als Papierticket Abo-Nummer (falls vorhanden) Tag Monat Jahr Name der Firma/Behörde/Gesellschaft/Institution (Angebot beinhaltet keine BahnCard 25) Zahlungsweise Wagenklasse Produktklasse (Zugart) Personalnummer Mitarbeiter Monatliche Abbuchung 1. Klasse ICE, IC/EC, Nahverkehr Jährliche Abbuchung 2. Klasse IC/EC, Nahverkehr nur Nahverkehr Abteilung Gewünschte Verbindung Schiene (Gesamtstrecke) Angebot von nach über Bus von nach über Ich möchte meinen persönlichen DB Job-Ticket-Umsatz (möglich ab einem Wert von 2000 Euro) für bahn.bonus (www.bahn.de/bahnbonus) Verbindung/Teilstrecke 1. Klasse (nur zu bestehendem Abo und identischer Geltungsdauer möglich) auf folgender BahnCard-Nummer sammeln: 7 0 8 1 von nach Ich bestelle o. g. Abonnement (bei unter 18-Jährigen der Erziehungsberechtigte) Frau Herr Titel Name Vorname Geburtsdatum Straße/Hausnummer Adresszusatz Staat Postleitzahl Ort E-Mail* Besteller Ja, ich möchte per Telefon über aktuelle Aktionen, neue Prämien Ja, ich möchte per E-Mail über aktuelle Aktionen, neue Prämien Telefon* sowie für mich zugeschnittene Angebote informiert werden. sowie für mich zugeschnittene Angebote informiert werden. Zugunsten von Geburtsdatum Name Vorname Ich bin bereits Abo-Kunde und kündige meine DB Jahreskarte im Abo Die Hinweise -

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020

Eighth Annual Market Monitoring Working Document March 2020 List of contents List of country abbreviations and regulatory bodies .................................................. 6 List of figures ............................................................................................................ 7 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 9 2. Network characteristics of the railway market ........................................ 11 2.1. Total route length ..................................................................................................... 12 2.2. Electrified route length ............................................................................................. 12 2.3. High-speed route length ........................................................................................... 13 2.4. Main infrastructure manager’s share of route length .............................................. 14 2.5. Network usage intensity ........................................................................................... 15 3. Track access charges paid by railway undertakings for the Minimum Access Package .................................................................................................. 17 4. Railway undertakings and global rail traffic ............................................. 23 4.1. Railway undertakings ................................................................................................ 24 4.2. Total rail traffic ......................................................................................................... -

Convenient and Environmentally-Friendly Train Travel: Travel with 100% Green Power to Events, Trade Fairs and Congresses from All Over Germany

Terms Event Ticket Seite 1 von 2 Convenient and environmentally-friendly train travel: Travel with 100% green power to Events, Trade fairs and congresses from all over Germany In cooperation with Event Organizer and Deutsche Bahn, you travel safely and conveniently to Events, Trade fairs and congresses. Help protect the environment: Travel with 100% green power to your event with Deutsche Bahn long-distance services.* The energy you require for your journey will originate from 100% renewable sources in Europe. Terms of the Event Ticket Specific-train Event Tickets with a specific train connection are only valid on the days and trains shown. prices: While stocks last. Book your ticket for a specific train connection, subject to availability. Flexible-train Book your ticket for use on any train , flexible and always available. prices: Bookable from: 3 months in advance to the first event day Earliest outward 2 days before the first event day journey: Latest return 2 days after the last event day journey: Advance- From 92 days up to 3 days before day of travel for specific-train tickets. purchase period: Flexible tickets can be purchased until directly before departure. Route: Valid for journeys to the Event location - next DB Station Products: ICE, Intercity (IC), Eurocity (EC). Regional connecting trains may be used before or after the long-distance journey. The use of night trains (EN, CNL) requires a special supplement. Ticket: Valid for outward and return journeys. Class: First class Second class ** The booking line is available from Monday to Saturday 07:00 am to 10:00 pm. -

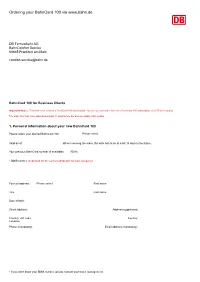

Ordering Your Bahncard 100 Via

Ordering your BahnCard 100 via www.bahn.de DB Fernverkehr AG BahnComfort Service 60645 Frankfurt am Main [email protected] BahnCard 100 for Business Clients Important Notice: This form is not valid for a BahnCard 100 subscription. You can get your order form for a BahnCard 100 subscription at all DB sales outlets. The order form has to be submitted at least 14 days before the desired validity starting date. 1. Personal information about your new BahnCard 100 Please select your desired BahnCard 100 Valid as of: When receiving the order, this date has to be at least 14 days in the future. Your previous BahnCard number (if available): 70814 * BMIS number (important for the correct attribution for your company): Form of address: First name: Title: Last name: Date of birth: Street Address: Address supplement: Country: ZIP code, Country: Location: Phone (mandatory): Email address (mandatory): * If you don‘t know your BMIS number, please contact your travel management. 2. Paying for your BahnCard 100 Card holder is a registered self-booker within the corporate programme with registered payment data (credit card) ** Internet client number of self-booker (mandatory information): Payment is to be effected via the following credit card: Type of card: Valid through: Credit card number: Date and signature corporate seal Account holder / credit card holder Notice for credit card payment: When purchasing a BahnCard 100, a payment fee of 3 euros may be charged. Learn more at www.bahn.de/zahlungsmittelentgelt 3. Registration for BahnBonus With BahnBonus, the travel and experience programme of Deutsche Bahn, you may collect tokens (points) for high-quality rewards, like upgrades or merchandise rewards. -

Financial Statements

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 62 STATEMENT OF INCOME 65 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL 76 LIST OF SHAREHOLDINGS STATEMENTS 62 BALANCE SHEET 86 AUDITOR’S REPORT > 67 Notes to the balance sheet > 62 Assets > 71 Notes to the statement > 86 Report on the financial > 62 Equity and liabilities of income statements > 86 Report on the management 63 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS > 72 Notes to the statement of cash flows report 64 FIXED AssETS SCHEDULE > 72 Other disclosures 62 DEUTSCHE BAHN AG 2014 MANAGEMENT REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS STATEMENT OF INCOME JAN 1 THROUGH DEC 31 [€ mILLION] Note 2014 2013 Inventory changes 0 0 Other internally produced and capitalized assets 0 – Overall performance 0 0 Other operating income (16) 1,179 1,087 Cost of materials (17) –95 –91 Personnel expenses (18) –324 –303 Depreciation –10 –12 Other operating expenses (19) –970 –850 –220 –169 Net investment income (20) 794 583 Net interest income (21) –67 –37 Result from ordinary activities 507 377 Taxes on income (22) 37 –10 Net profit for the year 544 367 Profit carried forward 4,531 4,364 Net retained profit 5,075 4,731 BALANCE SHEET AssETS [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. FIXED ASSETS Property, plant and equipment (2) 29 33 Financial assets (2) 26,836 27,298 26,865 27,331 B. CUrrENT ASSETS Inventories (3) 1 1 Receivables and other assets (4) 4,412 3,690 Cash and cash equivalents 3,083 2,021 7,496 5,712 C. PREpaYMENTS anD AccrUED IncoME (5) 0 1 34,361 33,044 EQUITY AND LIABILITIES [€ MILLION] Note Dec 31, 2014 Dec 31, 2013 A. -

Acquisition by Arriva Rail North Limited of the Northern Rail Franchise

Acquisition by Arriva Rail North Limited of the Northern rail franchise Summary of final report 2 November 2016 Background 1. On 20 May 2016, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), in the exercise of its duty under section 22(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (the Act), referred the completed acquisition by Arriva Rail North Limited (ARN), a wholly-owned subsidiary of Arriva plc (Arriva), of the Northern rail franchise (the Northern Franchise) (altogether the Merger) for further investigation and report by a group of CMA panel members (inquiry group). Throughout this document, where appropriate, we refer to Arriva, ARN and the Northern Franchise collectively as ‘the Parties’. 2. In exercise of its duty under section 35(1) of the Act, the CMA must decide: (a) whether a relevant merger situation has been created; and (b) if so, whether the creation of that situation has resulted or may be expected to result in a substantial lessening of competition (SLC) within any market or markets in the United Kingdom (UK) for goods or services. The rail and bus sectors in Great Britain 3. Franchised train operating companies (franchised TOCs) operate passenger rail franchises and are awarded the right to run specific services within a specified area for a specific period of time, in return for the right to charge fares. Where appropriate, franchised TOCs receive financial support from the franchising authority, which is currently the Rail Group in the Department for Transport (DfT).1 There are currently 16 franchises operating in England and Wales and two in Scotland. 1 Transport Scotland is the franchising authority for the ScotRail and Caledonian Sleeper franchises. -

Retail Market Review Consultation on the Potential Impacts of Regulation and Industry Arrangements and Practices for Ticket Selling

Retail market review Consultation on the potential impacts of regulation and industry arrangements and practices for ticket selling September 2014 Contents Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 10 Purpose of the document 10 Why we are reviewing the regulations and industry arrangements and practices for ticket selling 11 Scope of the Review 12 Approach to the Review 13 Structure of the document 14 Questions for Chapter 1 15 2. Rail ticket buying and selling practices 16 Introduction 16 Ticket buying trends in rail 16 Ticket selling behaviour in rail 18 Questions for Chapter 2 22 3. The regulation and industry arrangements and practices for selling tickets 24 Introduction 24 Retailers’ incentives to sell tickets 25 Obligations on retailers to facilitate an integrated, national network 26 Governance arrangements in retailing 29 Industry rules 32 Industry processes and systems 34 Question for Chapter 3 37 4. The impact of retailers’ incentives and of retailers’ obligations to facilitate an integrated, national network 38 Introduction 38 The impact of retailers’ incentives in selling tickets 38 The impact of obligations on retailers to facilitate an integrated, national network 40 Questions for Chapter 4 44 5. The impact of industry governance, rules, processes, and systems 45 Introduction 45 The impact of industry governance arrangements 45 Office of Rail Regulation | September 2014 | Retail market review consultation 2 10866832 The impact of industry rules 47 The impact of industry processes and systems 52 Questions for Chapter 5 58 6. Emerging -

East Midlands Rail Franchise

East Midlands Rail Franchise EMC Workshop 21st MARCH 2017 AGENDA Welcome Cllr Roger Blaney – Leader Newark and Sherwood District Council Setting the context for the day Andrew Pritchard - EMC Where has the process got to Andrew MacDonald - DfT What does the Passenger want Martin Clarke - Transport Focus Consultation and workshop process David Young - SCP Break out sessions – everyone involved Cllr Roger Blaney LEADER NEWARK AND SHERWOOD DISTRICT COUNCIL Welcome Welcome 2nd Workshop Strategic Statement Today: Develop the detail of our ask Inform EMC’s consultation response to DfT Help partners respond to the consultation Mobilise public and private sector awareness of the consultation Andrew Pritchard EAST MIDLANDS COUNCILS EMC & the EM Franchise Competition East Midlands Councils the collective body for Local Government across the East Midlands Strong interest in rail issues: improved services and supporting our world class rail engineering sector EMC closely working with DfT to facilitate stakeholder input on the EM Franchise – including seconding resource to work with DfT Franchise Team in London Chance to influence things for the next 10 years www.emcouncils.gov.uk EMC Strategic Statement Strong private sector job Connecting people to jobs growth and training 20% of GVA Exported Connecting businesses to Strong academic network customers EM population likely to rise by half a million to 5.1 million Access to London by 2030 Connectivity to regional Hubs Biggest growth in university towns & cities - and Corby! Connecting local services 400,000 new homes planned into the Hub towns and cities over next 20 years Growth: Rail Patronage MML carries over 13 Ensure sufficient capacity million passenger p.a.