Jn 3/D Aio.THOS'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

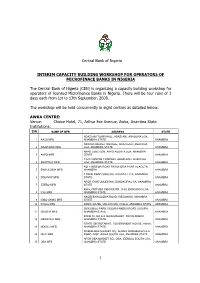

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Dictionary of Ò,Nì,Chà Igbo

Dictionary of Ònìchà Igbo 2nd edition of the Igbo dictionary, Kay Williamson, Ethiope Press, 1972. Kay Williamson (†) This version prepared and edited by Roger Blench Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm To whom all correspondence should be addressed. This printout: November 16, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations: ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Editor’s Preface............................................................................................................................................... 1 Editor’s note: The Echeruo (1997) and Igwe (1999) Igbo dictionaries ...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Earlier lexicographical work on Igbo........................................................................................................ 4 2. The development of the present work ....................................................................................................... 6 3. Onitsha Igbo ................................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Alphabetization and arrangement.......................................................................................................... -

Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality

UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama (eds.) Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH i No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Umeå Papers in English Printed in Sweden by the Printing Office of Umeå University Umeå 1992 ISSN 0280-5391 Table of Contents Raoul Granqvist and Nnadozie Inyama: Introduction Chukwuma Azuonye: Power, Marginality and Womanbeing i n Igbo Oral Narratives Christine N. Ohale: Women in Igbo Satirical Song Afam N. Ebeogu: Feminist Temperament in Igbo Birth Songs Ambrose A. Monye: Women in Nigerian Folklore: Panegyric and Satirical Poems on Women in Anicha Igbo Oral Poetry N. Chidi Okonkwo: Maker and Destroyer: Woman in Aetiological Tales Damian U. Opata: Igbo A ttitude to Women: A Study of a Prove rb Nnadozie Inyama: The "Rebe l Girl" in West African Liter ature: Variations On a Folklore Theme About the writers iii Introduction The idea of a book of essays on West African women's oral literature was first mooted at the Chinua Achebe symposium in February 1990, at Nsukka, Nigeria. Many of the papers dwelt on the image and role of women in contemporary African literature with, of course, particular attention to their inscriptions in Achebe's fiction. We felt, however, that the images of women as they have been presented by both African men and women writers and critics would benefit from being complement ed, fragmented and tested and that a useful, albeit complex, site for this inquiry could be West African oral representations of the female. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

State: Anambra Code: 04

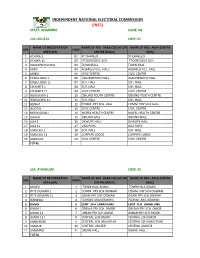

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ANAMBRA CODE: 04 LGA :AGUATA CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ACHINA 1 01 ST CHARLED ST CHARLED 2 ACHINA 11 02 PTOGRESSIVE SCH. PTOGRESSIVE SCH. 3 AGULEZECHUKWU 03 TOWN HALL TOWN HALL 4 AKPO 04 AGBAELU VILL. HALL AGBAELU VILL. HALL 5 AMESI 05 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 6 EKWULOBIA 1 06 UMUEZENOFO HALL. UMUEZENOFO HALL. 7 EKWULOBIA 11 07 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 8 EZENIFITE 1 08 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 9 EZENIFITE 11 09 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 10 IGBOUKWU 1 10 OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE 11 IGBOUKWU 11 11 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 12 IKENGA 12 COMM. PRY SCH. HALL COMM. PRY SCH. HALL 13 ISUOFIA 13 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 14 NKPOLOGWU 14 MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE 15 ORAERI 15 OBIUNO HALL OBIUNO HALL 16 UGA 1 16 OKWUTE HALL OKWUTE HALL 17 UGA 11 17 UGA BOYS UGA BOYS 18 UMUCHU 1 18 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 19 UMUCHU 11 19 CORPERS LODGE CORPERS LODGE 20 UMOUNA 20 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE TOTAL LGA: AYAMELUM CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ANAKU 1 TOWN HALL ANAKU TOWN HALL ANAKU 2 IFITE OGWARI 1 2 COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI 3 IFITE OGWARI 11 3 OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI 4 IGBAKWU 4 ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU 5 OMASI 5 CENT. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 22, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. -

Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment

Hostalia ConsultaireE2924 NigerianNigerian Erosion Erosion and Watershed Managementand Watershed Project Management Health and EnvironmentProject NEWMAP Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Public Disclosure Authorized Framework (ESMF) FINAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Hostalia Consultaire Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project NEWMAP FINAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 2011 Prepared by Dr. O. A. Anyadiegwu Dr. V. C. Nwachukwu Engr. O. O. Agbelusi Miss C.I . Ikeaka 2 Hostalia Consultaire Nigerian Erosion and Watershed Management Project Health and Environment Table of Content Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................15 Background ..........................................................................................................................15 TRANSLATION IN IBO LANGUAGE..........................................................22 TRANSLATION IN EDO LANGUAGE.........................................................28 TRANSLATION IN EFIK...............................................................................35 CHAPTER ONE..............................................................................................43 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND TO NEWMAP.............................43 1.0 Background to the NEWMAP...................................................................................43 -

Malaria Prevalence and Indoor-Biting Mosquito Vector Abundance in Ogbunike, Oyi Local Government Area, Anambra State, Nigeria (Pp

An International Multi-Disciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 5 (3), Serial No. 20, May, 2011 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070-0083 (Online) Malaria Prevalence and Indoor-Biting Mosquito Vector Abundance in Ogbunike, Oyi Local Government Area, Anambra State, Nigeria (Pp. 1-13) Onyido, A. E. - Department of Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Biosciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, P.M.B. 5025, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. Obi, N. C. - Department of Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Biosciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, P.M.B. 5025, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. Umeanaeto, P. U. - Department of Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Biosciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, P.M.B. 5025, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] Obiukwu, M.O. - Department of Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Biosciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, P.M.B. 5025, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. Egbuche, M.C. - Department of Parasitology and Entomology, Faculty of Biosciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, P.M.B. 5025, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria. Abstract This paper studies malaria prevalence and the abundance of indoor-biting mosquito vectors in Ogbunike community, Oyi Local Government Area of Anambra State, Nigeria between May and September 2010. Blood samples were collected from 208 healthy participants (94 males and 114 females) Copyright (c) IAARR, 2011: www.afrrevjo.com 1 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 5 (3), Serial No. 20, May, 2011. Pp. 1-13 selected from the six villages of the town. Thick and thin blood films were made, stained with Field’s stains A and B and examined microscopically. Indoor-biting mosquito vectors were collected using Pyrethrum Knockdown Collection method (PKC). -

Economic Impacts of Prolonged Little Dry Season (August Break) in a Climatic Changed Era in Agrarian Communities of Anambra River Basin, Anambra State, Nigeria

Socio – Economic Impacts of Prolonged Little Dry Season (August Break) in a Climatic Changed Era in Agrarian Communities of Anambra River Basin, Anambra State, Nigeria Romanus Udegbunam Ayadiuno1; Dominic Chukwuka2 1Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. 2Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. [email protected] Abstract The food supply and demand situation for the 2020 fiscal year concerning the main seasonal crops in Nigeria was unpredictable due to the effect of Covid-19 pandemic. Federal and state governments laid much emphasis as a result on agriculture, especially crop production in order to produce food enough to ameliorate hunger, which is one of the negative effects of Covid-19. Nigeria been a rain fed dependent agricultural nation, follows the dictate of weather and other weather elements in her agricultural activities. With climate change and the effect of Little Dry Season, there was a reduction in rainfall in mid-July through August 2020. Rice and Maize which are among the staple foods in Nigeria requires about 750mm to 1200mm of rainfall to thrive. The mean monthly rainfall recorded in our study area (part of Anambra River Basin) consisting of Ayamelum, Anambra West, Anambra East, Oyi and Dunukofia local government areas are 21.15mm and 3.25mm for July, 2020 and August, 2020 respectively. As a result of the shortage of rainfall in these two months, the farmers and the authors observed these negative outcomes which are early maturity of crops; early harvesting of crops as well as poor yields for early season crops. -

(ESMP) for the Amachalla Gully Erosion Site

Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) Draft Report Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) for the Amachalla Gully Erosion Site Awka South, Anambra State. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized [Document title] [Document subtitle] Abstract [Draw your reader in with an engaging abstract. It is typically a short summary of the document. When you’re ready to add your content, just click here and start typing.] Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared for the State Project Management Unit (SPMU) Anambra State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project [Email address] Draft Report for the Amachalla gully erosion site Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project (NEWMAP) Draft Report Environmental and Social Management (ESMP) for the Amachalla Gully Erosion Site Awka, Anambra State Prepared for the State Project Management Unit (SPMU) Anambra State Nigeria Erosion and Watershed Management Project ii Draft Report for the Amachalla gully erosion site Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................................................... IV LIST OF PHOTOS ...................................................................................................................................... V LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................................... V EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..............................................................................................................