I Linguistics, Igbo and Other Nigerian Languages Webmaster 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

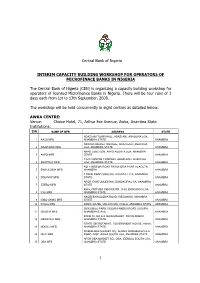

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

Proverb Usage in African Literature

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org Volume 4 Issue 3 || March. 2015 || PP. 30-35 Proverb Usage in African Literature 1Adaobi Olivia Ihueze, 2 Prof. Rems Umeasiegbu 1Department of English Language and Literature,Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Nigeria. 2 Department of English Language and Literature, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Nigeria ABSTRACT: This study analyzes the integration of proverbs in Flora Nwapa’s Efuru and Elechi Amadi’s The Concubine and The Great Ponds that is their active and passive usages. The proverbs were isolated and related to available data in published works to ensure that they are real oral lore. Rems Umeasiegbu’s reflective model for assessment of Igbo proverbs that was used to test Chinua Achebe’s works was used to asses Flora Nwapa and Elechi Amadi’s use”of proverbs. They tallied. The model shows that they have really used proverbs effectively. The work concludes that the model for the study of proverbs used in Achebe’s novels fits very well the proverbs used by Flora Nwapa and Elechi Amadi. KEY WORDS: Active, assessment, folklore, passive, proverb and reflective, I. INTRODUCTION Proverbs are essential to life and language, and without them, the language will be but a skeleton without flesh, a body without a soul. It is also used to add colour to every conversation. In the foreword to W. H. Whitely‟s Selection of African Prose,(1964) the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe says this about a proverb … In Igbo they serve two important ends. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Dictionary of Ò,Nì,Chà Igbo

Dictionary of Ònìchà Igbo 2nd edition of the Igbo dictionary, Kay Williamson, Ethiope Press, 1972. Kay Williamson (†) This version prepared and edited by Roger Blench Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm To whom all correspondence should be addressed. This printout: November 16, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations: ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Editor’s Preface............................................................................................................................................... 1 Editor’s note: The Echeruo (1997) and Igwe (1999) Igbo dictionaries ...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Earlier lexicographical work on Igbo........................................................................................................ 4 2. The development of the present work ....................................................................................................... 6 3. Onitsha Igbo ................................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Alphabetization and arrangement.......................................................................................................... -

Post-Colonial Literature: Chinua Achebe

Aula 4 POST-COLONIAL Literature: CHINUA ACHEBE META Introduce students to Chinua Achebe’s life and work OBJETIVO Ao final desta aula, você deverá ser capaz de: Outline a short biography of Chinua Achebe, placing some emphasis on his contribution to what could be loosely called ‘African literature’. Make a concise presentation of Achebe’s novels and a list of his short stories and poems. PRERREQUISITO Notions about the historicity of the concept of literature; Notions of the process of formation and institutionalization of Literary History and literary theory as disciplines that have in Literature its object of study. Notions of the relationship between Literary History and literature teaching. Luiz Eduardo Oliveira José Augusto Batista dos Santos Literatura de Língua Inglesa VI INTRODUÇÃO In this lesson, we will be studying Chinua Achebe, a very important author in African literature. He was born in Nigeria on November 16th 1930 in the Igbo village of Ogidi. His real name was Albert Chinualumogu Achebe. Although his parents had been converted into Christianity by missionaries from the Protestant Church Mission Society (CMS), Achebe’s father seemed to respect his ancestor’s traditions, of which fact the name Chinualumogu is a reminder, since it is a prayer for divine protection and stability that could be translated as “May God fight on my behalf ”. Having to live between two worlds, namely, that of Christianity and that of tradi- tional beliefs has no doubt played a significant role in Achebe’s education and, later, in his work. He was born Albert Chinualumogụ Achebe, 16 November 1930 – 21 March 2013. -

No Longer at Ease by Chinua Achebe

No Longer at Ease by Chinua Achebe Review by: Lauren Evans From the author of Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God comes Chinua Achebe’s No Longer at Ease, his second book in the African trilogy and one that was published in 1960, the year Nigeria received its independence from England. I had already read the first and third book in this trilogy and was excited to pick this one up. The book is set in the 1950s with Obi Okonkwo, the grandson of main character Okonkwo from Things Fall Apart, returning to Nigeria from England, where he had gone to receive his education. The story opens with Obi on trial for having accepted a bribe, then goes back to the pre-trial past to give us an idea of how he ended up there and ends with the story returning full circle. Obi went to England on scholarship to pursue a degree in English. After returning to Nigeria and his hometown of Umuofia, he takes a position with the Scholarship Board as the Administrative Assistant to the Inspector of Schools. Soon after, he’s offered a bribe by a man who is trying to get a scholarship for his little sister. The girl even visits Obi and offers to bribe him with sex, but Obi turns it down, even though he is tempted because of severe financial hardship. While all this is going on, Obi develops a romantic relationship with Clara Okeke, a Nigerian woman he met while in England who is an “osu,” an outcast looked down upon by her descendants. -

Chinua Achebe's Girls at War and Other Stories

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Chinua Achebe’s Girls at War and other Stories: A Relevance-Theoretical Interpretation Adaoma Igwedibia1*, Christian Anieke2, Ezeaku Kelechi Virginia1 1Department of English and Literary Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria 2Department of English and Literary Studies, Godfrey Okoye University, Nigeria Corresponding Author: Adaoma Igwedibia, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history Relevance Theory (RT), which is a theory that takes the Gricean approach to communication as Received: January 26, 2019 a starting point of linguistic or literary analysis, is an influential theory in Pragmatics that was Accepted: March 09, 2019 developed by D. Sperber and D. Wilson (1986, 1995). As a cognitive theory of meaning (which Published: May 31, 2019 claims that semantic meaning is the result of linguistic decoding processes, whereas pragmatic Volume: 8 Issue: 3 meaning is the result of inferential processes constrained by one single principle, Principle of Advance access: April 2019 Relevance), its main assumption is that human beings are endowed with a biologically rooted ability to maximize the relevance of incoming stimuli. RT unifies the Gricean cooperative principle and his maxims into a single principle of relevance that motivates the hearer’s Conflicts of interest: None inferential strategy. Based on the classic code model of communication and Grice’s inferential Funding: None model, RT holds that ‘every act of ostensive communication communicates a presumption of its own optimal relevance’. Literary texts which present us with a useful depth of written data that serve as repositions of language in use can be analyzed linguistically. -

Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality

UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama (eds.) Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH i No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Umeå Papers in English Printed in Sweden by the Printing Office of Umeå University Umeå 1992 ISSN 0280-5391 Table of Contents Raoul Granqvist and Nnadozie Inyama: Introduction Chukwuma Azuonye: Power, Marginality and Womanbeing i n Igbo Oral Narratives Christine N. Ohale: Women in Igbo Satirical Song Afam N. Ebeogu: Feminist Temperament in Igbo Birth Songs Ambrose A. Monye: Women in Nigerian Folklore: Panegyric and Satirical Poems on Women in Anicha Igbo Oral Poetry N. Chidi Okonkwo: Maker and Destroyer: Woman in Aetiological Tales Damian U. Opata: Igbo A ttitude to Women: A Study of a Prove rb Nnadozie Inyama: The "Rebe l Girl" in West African Liter ature: Variations On a Folklore Theme About the writers iii Introduction The idea of a book of essays on West African women's oral literature was first mooted at the Chinua Achebe symposium in February 1990, at Nsukka, Nigeria. Many of the papers dwelt on the image and role of women in contemporary African literature with, of course, particular attention to their inscriptions in Achebe's fiction. We felt, however, that the images of women as they have been presented by both African men and women writers and critics would benefit from being complement ed, fragmented and tested and that a useful, albeit complex, site for this inquiry could be West African oral representations of the female. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

The God and People's Power in Chinua Achebe's Arrow Of

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 2, Ver. 11 (February. 2018) PP 68-77 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The God And People’s Power In Chinua Achebe’s Arrow Of God 1 2 Afolabi Olarongbe Akanbi , Noor Hashima Abd Aziz , Rohizah Halim 3 1,2,3(School of Languages, Civilisation and Philosophy, UUM CAS, Universiti Utara Malaysia, 06010, Sintok, Kedah, Malaysia) 1(Department of Languages, Federal Polytechnic Offa, Kwara State, Nigeria) Corresponding Author: Afolabi Olarongbe Akanbi Abstract: Chinua Achebe has made the question of power one of the central concerns of his works. As a novelist, he has devoted considerable attention to the use of powers by leaders. In Arrow of God, Achebe focusses on Ezeulu, the Chief Priest and spiritual leader of Umuaro to address the question of who, between Ezeulu and the people of Umuaro, decides the wish of the god. This paper, using textual analysis and application of myth theory argues that Ezeulu‟s powers are derived from the myth of the founding of Umuaro and arising from this, the people believe that their wish should prevail in Ezeulu‟s discharge of his functions. The paper contends that the crisis of the New Yam Feast which set the people against Ezeulu is traceable to the refusal of the Chief Priest to let the wish of the people prevail. Umuaro people believe that their Chief Priest has failed to protect them at their trying moment, thus, they abandoned him and Ulu, their god. The paper find that when Ulu later intervenes on the side of the people, it affirms that they have a say in who decides the wish of the god. -

How Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka Reclaimed Nigerian Identity Through Their Writing

“The Story We Had To Tell:” How Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka Reclaimed Nigerian Identity Through Their Writing Clara Sophia Brodie Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in English April 2013 © 2013 Clara Sophia Brodie 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Religion Part I: Arrow of God 13 Part II: Death and the King’s Horseman 32 Chapter I: Education Part I: No Longer At Ease 52 Part II: The Interpreters 70 Chapter III: Language 90 Works Cited & Bibliography 117 3 Acknowledgements I would like to express my very great appreciation to my advisor Margery Sabin for her advice and support and for never accepting anything less than my best. I would also like to thank my thesis committee for their time and thoughtful consideration and my friends and family for their patience and love. Finally, I would like to acknowledge Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka whose timeless voices inspired this project. 4 Introduction For more than half a century the poems, plays and novels of Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka have defined African literature. Born just four years apart, these two Nigerian writers have led lives that are simultaneously similar and distinct. Their differences are obvious for example they have disparate origins within Nigeria— Achebe is Igbo1 and Soyinka Yoruba—but important common experiences invite comparisons between their lives and careers. To begin with, they share an index of national historical phenomena, from the history of colonization and independence, which came to Nigeria in 1960, to the continued political struggles against dictatorships and through civil war leading finally to their exile.