P.1 – 18, (ISSN: 2276-8645) CONFLI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

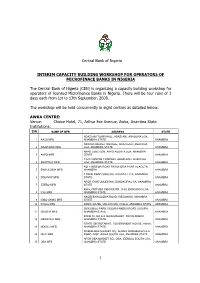

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

Historical Dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte Cultural Festival in Igboland, Nigeria

67 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 13, pp: 67 - 98 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i13.2 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Article Historical dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte cultural festival in Igboland, Nigeria Akachi Odoemene Department of History and International Studies, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] (Received 6 January 2020; Accepted 16 May 2020; Published 6 June 2020) Abstract - Ọjị (kola nut) is indispensable in traditional life of the Igbo of Nigeria. It plays an intrinsic role in almost all segments of the people‟s cultural life. In the Ọjị Ezinihitte festivity the „kola tradition‟ is meaningfully and elaborately celebrated. This article examines the importance of Ọjị within the context of Ezinihitte socio-cultural heritage, and equally accounts for continuity and change within it. An eclectic framework in data collection was utilized for this research. This involved the use of key-informant interviews, direct observation as well as extant textual sources (both published and un-published), including archival documents, for the purposes of the study. In terms of analysis, the study utilized the qualitative analytical approach. This was employed towards ensuring that the three basic purposes of this study – exploration, description and explanation – are well articulated and attained. The paper provided background for a proper understanding of the „sacred origin‟ of the Ọjị festive celebration. Through a vivid account of the festival‟s processes and rituals, it achieved a reconstruction of the festivity‟s origins and evolutionary trajectories and argues the festival as reflecting the people‟s spirit of fraternity and conviviality. -

SIGNIFICANCE of ANIMAL MOTIFS in INDIGENOUS ULI BODY and WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied A

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol. 8, No. 1. June 2019 SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS… Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor SIGNIFICANCE OF ANIMAL MOTIFS IN INDIGENOUS ULI BODY AND WALL PAINTINGS Nkiruka Jane Uju Nwafor Department of Fine and Applied Arts Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka. [email protected] This article explores the significance of animal motifs in traditional Uli body and wall paintings. A critical assessment and understanding of the philosophical import of animals in African concept of existence is vital for an in-depth appreciation of their (animals’) symbols in indigenous African artworks. This paper attempts to a draw parallel between traditional beliefs concerning certain animals among the Igbo of south-eastern Nigeria and motifs derived from indigenous Uli body and wall painting. In essence, the article sees animal motifs in Uli body and wall paintings as playing an aesthetic as well as metaphysical roles. Hence I argue that local nuances of religiosity and spirituality have historically imbued the animals with a heightened sense of sacredness in some Igbo communities thus allowing the animals to occupy a mystical space in Igbo cosmology. Introduction The pre-colonial system of knowledge transmission in Africa was not only through oral literature but also through the varied artistic traditions that survived from one generation to the other. The rich heritage of ancient Egyptian arts (including the hieroglyphs), the numerous Neolithic rock paintings and engravings found in Northern Africa, which dates back to 5000 and 2000 BCE respectively were mainly symbolic of vital occurrences of the past, documented through art (Getlein 2002: 335). -

The Igbo Traditional Food System Documented in Four States in Southern Nigeria

Chapter 12 The Igbo traditional food system documented in four states in southern Nigeria . ELIZABETH C. OKEKE, PH.D.1 . HENRIETTA N. ENE-OBONG, PH.D.1 . ANTHONIA O. UZUEGBUNAM, PH.D.2 . ALFRED OZIOKO3,4. SIMON I. UMEH5 . NNAEMEKA CHUKWUONE6 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems 251 Study Area Igboland Area States Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State Ubulu-Uku/Alumu in Delta State Lagos Nigeria Figure 12.1 Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State Ede-Oballa/Ukehe IGBO TERRITORY in Enugu State Participating Communities Data from ESRI Global GIS, 2006. Walter Hitschfield Geographic Information Centre, McGill University Library. 1 Department of 3 Home Science, Bioresources Development 5 Nutrition and Dietetics, and Conservation Department of University of Nigeria, Program, UNN, Crop Science, UNN, Nsukka (UNN), Nigeria Nigeria Nigeria 4 6 2 International Centre Centre for Rural Social Science Unit, School for Ethnomedicine and Development and of General Studies, UNN, Drug Discovery, Cooperatives, UNN, Nigeria Nsukka, Nigeria Nigeria Photographic section >> XXXVI 252 Indigenous Peoples’ food systems | Igbo “Ndi mba ozo na-azu na-anwu n’aguu.” “People who depend on foreign food eventually die of hunger.” Igbo saying Abstract Introduction Traditional food systems play significant roles in maintaining the well-being and health of Indigenous Peoples. Yet, evidence Overall description of research area abounds showing that the traditional food base and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples are being eroded. This has resulted in the use of fewer species, decreased dietary diversity due wo communities were randomly to household food insecurity and consequently poor health sampled in each of four states: status. A documentation of the traditional food system of the Igbo culture area of Nigeria included food uses, nutritional Ohiya/Ohuhu in Abia State, value and contribution to nutrient intake, and was conducted Ezinifite/Aku in Anambra State, in four randomly selected states in which the Igbo reside. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Research Report

1.1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Soil erosion is the systematic removal of soil, including plant nutrients, from the land surface by various agents of denudation (Ofomata, 1985). Water being the dominant agent of denudation initiates erosion by rain splash impact, drag and tractive force acting on individual particles of the surface soil. These are consequently transported seizing slope advantage for deposition elsewhere. Soil erosion is generally created by initial incision into the subsurface by concentrated runoff water along lines or zones of weakness such as tension and desiccation fractures. As these deepen, the sides give in or slide with the erosion of the side walls forming gullies. During the Stone Age, soil erosion was counted as a blessing because it unearths valuable treasures which lie hidden below the earth strata like gold, diamond and archaeological remains. Today, soil erosion has become an endemic global problem, In the South eastern Nigeria, mostly in Anambra State, it is an age long one that has attained a catastrophic dimension. This environmental hazard, because of the striking imprints on the landscape, has sparked off serious attention of researchers and government organisations for sometime now. Grove(1951); Carter(1958); Floyd(1965); Ofomata (1964,1965,1967,1973,and 1981); all made significant and refreshing contributions on the processes and measures to combat soil erosion. Gully Erosion is however the prominent feature in the landscape of Anambra State. The topography of the area as well as the nature of the soil contributes to speedy formation and spreading of gullies in the area (Ofomata, 2000);. 1.2 Erosion Types There are various types of erosion which occur these include Soil Erosion Rill Erosion Gully Erosion Sheet Erosion 1.2.1 Soil Erosion: This has been occurring for some 450 million years, since the first land plants formed the first soil. -

Dictionary of Ò,Nì,Chà Igbo

Dictionary of Ònìchà Igbo 2nd edition of the Igbo dictionary, Kay Williamson, Ethiope Press, 1972. Kay Williamson (†) This version prepared and edited by Roger Blench Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm To whom all correspondence should be addressed. This printout: November 16, 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations: ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Editor’s Preface............................................................................................................................................... 1 Editor’s note: The Echeruo (1997) and Igwe (1999) Igbo dictionaries ...................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Earlier lexicographical work on Igbo........................................................................................................ 4 2. The development of the present work ....................................................................................................... 6 3. Onitsha Igbo ................................................................................................................................................ 9 4. Alphabetization and arrangement.......................................................................................................... -

Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality

UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama (eds.) Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality UMEÅ PAPERS IN ENGLISH i No. 15 Power and Powerlessness of Women in West African Orality edited by Raoul Granqvist & Nnadozie Inyama Umeå 1992 Umeå Papers in English Printed in Sweden by the Printing Office of Umeå University Umeå 1992 ISSN 0280-5391 Table of Contents Raoul Granqvist and Nnadozie Inyama: Introduction Chukwuma Azuonye: Power, Marginality and Womanbeing i n Igbo Oral Narratives Christine N. Ohale: Women in Igbo Satirical Song Afam N. Ebeogu: Feminist Temperament in Igbo Birth Songs Ambrose A. Monye: Women in Nigerian Folklore: Panegyric and Satirical Poems on Women in Anicha Igbo Oral Poetry N. Chidi Okonkwo: Maker and Destroyer: Woman in Aetiological Tales Damian U. Opata: Igbo A ttitude to Women: A Study of a Prove rb Nnadozie Inyama: The "Rebe l Girl" in West African Liter ature: Variations On a Folklore Theme About the writers iii Introduction The idea of a book of essays on West African women's oral literature was first mooted at the Chinua Achebe symposium in February 1990, at Nsukka, Nigeria. Many of the papers dwelt on the image and role of women in contemporary African literature with, of course, particular attention to their inscriptions in Achebe's fiction. We felt, however, that the images of women as they have been presented by both African men and women writers and critics would benefit from being complement ed, fragmented and tested and that a useful, albeit complex, site for this inquiry could be West African oral representations of the female. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Women's Access to Political Power in Ancient Egypt And

WOMEN’S ACCESS TO POLITICAL POWER IN ANCIENT EGYPT AND IGBOLAND: A CRITICAL STUDY A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Antwanisha V. Alameen January 2013 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, Advisory Chair, African American Studies Dr. Ama Mazama, African American Studies Dr. Kimmika Williams-Witherspoon, Theater Dr. Adisa Alkebulan, External Member, San Diego State University i Copyright By Antwanisha Alameen 2012 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This is an Afrocentric examination of women’s use of agency in Ancient Egypt and Igboland. Most histories written on Kemetic women not only disconnect them from Africa but also fail to fully address the significance of their position within the political spiritual structure of the state. Additionally, the presence of matriarchy in Ancient Egypt is dismissed on the basis that patriarchy is the most visible and seemingly the most dominant form of governance. Diop contended that matriarchy was one of the key factors that connected Ancient Egypt with other parts of Africa which is best understood as the Africa’s cultural continuity theory. My research analyzes the validity of his theory by comparing how Kemetic women exercised agency in their political structure to how Igbo women exercised political agency. I identified Igbo women as a cultural group to be compared to Kemet because of their historical political resistance in their state during the colonial period. However, it is their traditional roles prior to British invasion that is most relevant to my study. I define matriarchy as the central role of the mother in the social and political function of societal structures, the political positions occupied by women that inform the decisions of the state and the inclusion of female principles within the religious-political order of the nation. -

States and Lcdas Codes.Cdr

PFA CODES 28 UKANEFUN KPK AK 6 CHIBOK CBK BO 8 ETSAKO-EAST AGD ED 20 ONUIMO KWE IM 32 RIMIN-GADO RMG KN KWARA 9 IJEBU-NORTH JGB OG 30 OYO-EAST YYY OY YOBE 1 Stanbic IBTC Pension Managers Limited 0021 29 URU OFFONG ORUKO UFG AK 7 DAMBOA DAM BO 9 ETSAKO-WEST AUC ED 21 ORLU RLU IM 33 ROGO RGG KN S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 10 IJEBU-NORTH-EAST JNE OG 31 SAKI-EAST GMD OY S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 2 Premium Pension Limited 0022 30 URUAN DUU AK 8 DIKWA DKW BO 10 IGUEBEN GUE ED 22 ORSU AWT IM 34 SHANONO SNN KN CODE CODE 11 IJEBU-ODE JBD OG 32 SAKI-WEST SHK OY CODE CODE 3 Leadway Pensure PFA Limited 0023 31 UYO UYY AK 9 GUBIO GUB BO 11 IKPOBA-OKHA DGE ED 23 ORU-EAST MMA IM 35 SUMAILA SML KN 1 ASA AFN KW 12 IKENNE KNN OG 33 SURULERE RSD OY 1 BADE GSH YB 4 Sigma Pensions Limited 0024 10 GUZAMALA GZM BO 12 OREDO BEN ED 24 ORU-WEST NGB IM 36 TAKAI TAK KN 2 BARUTEN KSB KW 13 IMEKO-AFON MEK OG 2 BOSARI DPH YB 5 Pensions Alliance Limited 0025 ANAMBRA 11 GWOZA GZA BO 13 ORHIONMWON ABD ED 25 OWERRI-MUNICIPAL WER IM 37 TARAUNI TRN KN 3 EDU LAF KW 14 IPOKIA PKA OG PLATEAU 3 DAMATURU DTR YB 6 ARM Pension Managers Limited 0026 S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 12 HAWUL HWL BO 14 OVIA-NORTH-EAST AKA ED 26 26 OWERRI-NORTH RRT IM 38 TOFA TEA KN 4 EKITI ARP KW 15 OBAFEMI OWODE WDE OG S/N LGA NAME LGA STATE 4 FIKA FKA YB 7 Trustfund Pensions Plc 0028 CODE CODE 13 JERE JRE BO 15 OVIA-SOUTH-WEST GBZ ED 27 27 OWERRI-WEST UMG IM 39 TSANYAWA TYW KN 5 IFELODUN SHA KW 16 ODEDAH DED OG CODE CODE 5 FUNE FUN YB 8 First Guarantee Pension Limited 0029 1 AGUATA AGU AN 14 KAGA KGG BO 16 OWAN-EAST -

State: Anambra Code: 04

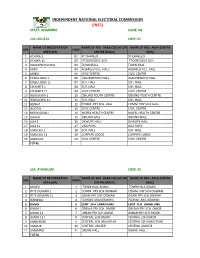

INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION (INEC) STATE: ANAMBRA CODE: 04 LGA :AGUATA CODE: 01 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ACHINA 1 01 ST CHARLED ST CHARLED 2 ACHINA 11 02 PTOGRESSIVE SCH. PTOGRESSIVE SCH. 3 AGULEZECHUKWU 03 TOWN HALL TOWN HALL 4 AKPO 04 AGBAELU VILL. HALL AGBAELU VILL. HALL 5 AMESI 05 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 6 EKWULOBIA 1 06 UMUEZENOFO HALL. UMUEZENOFO HALL. 7 EKWULOBIA 11 07 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 8 EZENIFITE 1 08 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 9 EZENIFITE 11 09 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 10 IGBOUKWU 1 10 OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE OBIUNO YOUTH CENTRE 11 IGBOUKWU 11 11 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 12 IKENGA 12 COMM. PRY SCH. HALL COMM. PRY SCH. HALL 13 ISUOFIA 13 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE 14 NKPOLOGWU 14 MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE MOFEL HEALTH CENTRE 15 ORAERI 15 OBIUNO HALL OBIUNO HALL 16 UGA 1 16 OKWUTE HALL OKWUTE HALL 17 UGA 11 17 UGA BOYS UGA BOYS 18 UMUCHU 1 18 SCH. HALL SCH. HALL 19 UMUCHU 11 19 CORPERS LODGE CORPERS LODGE 20 UMOUNA 20 CIVIC CENTRE CIVIC CENTRE TOTAL LGA: AYAMELUM CODE: 02 NAME OF REGISTRATION NAME OF REG. AREA COLLATION NAME OF REG. AREA CENTRE S/N CODE AREA (RA) CENTRE (RACC) (RAC) 1 ANAKU 1 TOWN HALL ANAKU TOWN HALL ANAKU 2 IFITE OGWARI 1 2 COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI COMM. PRY SCH.OGWARI 3 IFITE OGWARI 11 3 OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI OGARI PRY SCH.OGWARI 4 IGBAKWU 4 ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU ISIOKWE ARA,IGBAKWU 5 OMASI 5 CENT.