The Changing Performance Dynamic of Morecambe and Wise Hewett, RJ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There Are 16 Primary and 2 Secondary

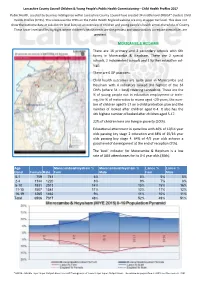

Lancashire County Council Children & Young People’s Public Health Commissioning—Child Health Profiles 2017 Public Health, assisted by Business Intelligence within Lancashire County Council have created 34 middle level (MSOA* cluster) Child Health Profiles (CHPs). This is because the CHPs on the Public Health England website are only at upper tier level. This does not show the outcome data at sub-district level but just an overview of children and young people’s health across the whole of County. These lower level profiles highlight where children’s health needs are the greatest and opportunities to reduce inequalities are greatest. MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There are 16 primary and 2 secondary schools with 6th forms in Morecambe & Heysham. There are 2 special schools, 2 independent schools and 1 further education col- lege. There are 6 GP practices. Child health outcomes are quite poor in Morecambe and Heysham with 4 indicators ranked 3rd highest of the 34 CHPs (where 34 = best) covering Lancashire. These are the % of young people not in education employment or train- ing, the % of maternities to mums aged <20 years, the num- ber of children aged 5-17 on a child protection plan and the number of looked after children aged 0-4. It also has the 4th highest number of looked after children aged 5-17. 22% of children here are living in poverty (10th). Educational attainment in quite low with 46% of 10/11 year olds passing key stage 2 education and 48% of 15/16 year olds passing key stage 4. 64% of 4/5 year olds achieve a good level of development at the end of reception (7th). -

Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2017 On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era Amanda Kay Martin University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Amanda Kay, "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/ Colbert Era. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4759 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Amanda Kay Martin entitled "On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Communication and Information. Barbara Kaye, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Mark Harmon, Amber Roessner Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) On with the Motley: Television Satire and Discursive Integration in the Post-Stewart/Colbert Era A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Amanda Kay Martin May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Amanda Kay Martin All rights reserved. -

Peat Database Results Lancashire

Bare, Lancashire Record ID 236 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 443 649 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat layer (often <1 m thick, hard, consolidated, dry, laminated deposit). Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Boreholes SD46 SW/52-54 Depth of deposit 14C ages available -10 m OD No Notes Bibliographic reference Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. 1998 'Geology of the country around Lancaster', Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheet 59 (England and Wales), . Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 31 Bare, Lancashire Record ID 237 Authors Year Crofton, A. 1876 Location description Deposit location SD 445 651 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat horizon resting on blue organic clay. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available No Notes Crofton (1876) referred to in Brandon et al (1998). Possibly same layer as mentioned by Reade (1904). Bibliographic reference Crofton, A. 1876 'Drift, peat etc. of Heysman [Heysham], Morecambe Bay', Transactions of the Manchester Geological Society, 14, 152-154. Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 2 of 31 Carnforth coastal area, Lancashire Record ID 245 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 4879 6987 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Coastal peat up to 4.9 m thick. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Borehole SD 46 NE/1 Depth of deposit 14C ages available Varying from near-surface to at-surface. -

The President of the Noël Coward Society

The Newsletter Of The Noël Coward Society October 2005 FREE TO MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY CHAT Price £3 ($5) The Presidenthome of The Noël Coward Society His Royal Highness The Duke of Kent The Society is delighted to announce Sid Field Benefit…….Highest spot – that His Royal Highness, The Duke of Judy Garland.” Kent, KG, GCMG, CVO, ADC, has As the years passed there were other accepted our invitation to become the references, some more fleeting than oth- Society’s President, succeeding the late ers: “Lunched with the Duchess and Sir John Mills, CBE. Princess Alexandra”, “had tea with This is a fitting tribute to the long Princess Marina”, and so on. friendship of His Royal Highness’s par- Noël was a genuine friend who ents, the late Prince George, Duke of adored being with the Duchess, whether Kent and Princess Marina, with Noël. entertaining her in lavish style, or mere- Prince George was the fourth son of ly dropping in for a quiet chat over a King George V, and Princess Marina drink or two. Princess Marina died in was the daughter of Prince Nicholas of 1968, aged only 61, from an inoperable Greece. The couple married in 1934 and brain tumour. Noël visited her for tea were regarded as the most attractive, on the day she returned from hospital popular and, above all, stylish royal cou- and wrote afterwards, “She was in bed ple of their generation. Prince George and looked very papery. I am worried g r o . met Noël in 1923, just as his career was about her. -

Preliminary Ecological Appraisal Slyne-With-Hest, Lancaster

LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION – SLYNE-WITH-HEST PRELIMINARY ECOLOGICAL APPRAISAL SLYNE-WITH-HEST, LANCASTER Provided for: Lancaster City Council Date: February 2016 Provided by: The Greater Manchester Ecology Unit Clarence Arcade Stamford Street Ashton-under-Lyne Tameside OL6 7PT Tel: 0161 342 4409 LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST QUALITY ASSURANCE Author Suzanne Waymont CIEEM Checked By Stephen Atkins Approved By Derek Richardson Version 1.0 Draft for Comment Reference LSA - 4 The survey was carried out in accordance with the Phase 1 habitat assessment methods (JNCC 2010) and Guidelines for Preliminary Ecological Appraisal (CIEEM 2013). All works associated with this report have been undertaken in accordance with the Code of Professional Conduct for the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management. (www.cieem.org.uk) LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST CONTENTS SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 SURVEY BRIEF 1.2 SITE LOCATION & PROPOSAL 1.3 PERSONNEL 2 LEGISLATION AND POLICY 3 METHODOLOGY 3.1 DESK STUDY 3.2 FIELD SURVEY 3.3 SURVEY LIMITATIONS 4 BASELINE ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS 4.1 DESKTOP SEARCH 4.2 SURVEY RESULTS 5 ECOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS – IMPLICATIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS 6 CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES APPENDIX 1 – DATA SEARCH RESULTS APPENDIX 2 – DESIGNATED SITES APPENDIX 3 – BIOLOGICAL HERITAGE SITES LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST SUMMARY • A Preliminary Ecological Appraisal was commissioned by Lancaster City Council to identify possible ecological constraints that could affect the development of 8 sites and areas currently being considered as new site allocations under its Local Plan. This report looks at one of these sites: Slyne-with-Hest. -

The Seaside Resorts of Westmorland and Lancashire North of the Sands in the Nineteenth Century

THE SEASIDE RESORTS OF WESTMORLAND AND LANCASHIRE NORTH OF THE SANDS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY BY ALAN HARRIS, M.A., PH.D. READ 19 APRIL 1962 HIS paper is concerned with the development of a group of Tseaside resorts situated along the northern and north-eastern sides of Morecambe Bay. Grange-over-Sands, with a population in 1961 of 3,117, is the largest member of the group. The others are villages, whose relatively small resident population is augmented by visitors during the summer months. Although several of these villages have grown considerably in recent years, none has yet attained a population of more than approxi mately 1,600. Walney Island is, of course, exceptional. Since the suburbs of Barrow invaded the island, its population has risen to almost 10,000. Though small, the resorts have an interesting history. All were affected, though not to the same extent, by the construction of railways after 1846, and in all of them the legacy of the nineteenth century is still very much in evidence. There are, however, some visible remains and much documentary evidence of an older phase of resort development, which preceded by several decades the construction of the local railways. This earlier phase was important in a number of ways. It initiated changes in what were then small communities of farmers, wood-workers and fishermen, and by the early years of the nineteenth century old cottages and farmsteads were already being modified to cater for the needs of summer visitors. During the early phase of development a handful of old villages and hamlets became known to a select few. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, and NOWHERE: a REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY of AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS by G. Scott Campbell Submitted T

PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS BY G. Scott Campbell Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chairperson Committee members* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* _____________________________* Date defended ___________________ The Dissertation Committee for G. Scott Campbell certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PERFECTION, WRETCHED, NORMAL, AND NOWHERE: A REGIONAL GEOGRAPHY OF AMERICAN TELEVISION SETTINGS Committee: Chairperson* Date approved: ii ABSTRACT Drawing inspiration from numerous place image studies in geography and other social sciences, this dissertation examines the senses of place and regional identity shaped by more than seven hundred American television series that aired from 1947 to 2007. Each state‘s relative share of these programs is described. The geographic themes, patterns, and images from these programs are analyzed, with an emphasis on identity in five American regions: the Mid-Atlantic, New England, the Midwest, the South, and the West. The dissertation concludes with a comparison of television‘s senses of place to those described in previous studies of regional identity. iii For Sue iv CONTENTS List of Tables vi Acknowledgments vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The Mid-Atlantic 28 3. New England 137 4. The Midwest, Part 1: The Great Lakes States 226 5. The Midwest, Part 2: The Trans-Mississippi Midwest 378 6. The South 450 7. The West 527 8. Conclusion 629 Bibliography 664 v LIST OF TABLES 1. Television and Population Shares 25 2. -

Bring Me Sunshine Reflect , Rewind and Replay

Geography PE English - Making and following maps of Morecambe Athletics. Class Poetry – Owl and the - Map symbols Outdoor and Adventurous Activities Pussy Cat Bikeability Stories by the Same Author Swimming Persuasion – making leaflets of Morecambe’s attractions now and in the past. History Frances Bowes – History of our school and church. RE Maths Eric Morecambe – Albert Modley Shape – Link with Art Winter Gardens – History of Morecambe – Midland Hotel The Bible – Stories Station building Problem Solving Investigations. Use strategies, such as scanning, skimming, and using an index to locate information. Offer evidence to support reasoning. Computing Internet research of Old Morecambe Music Eric Morecambe Off Songs from Eric Morecambe and his era Looking after ourselves – online. Bring me Sunshine Reflect , rewind and replay. – Offe Lancashire music. PSHE Sea safety Science Looking after ourselves in the holidays. Humans – How we grow and stay healthy. Relationships – how to keep them healthy What do we eat? How we look after our bodies. Relationships What happens to our bodies when we exercise DT Making a healthy meal I recognise the feelings of Learning about food groups • others. Predict and anticipate events. Record Information using formats they have •I can spot the causes of derived. Art other people’s feelings. Pencil sketching of Morecambe and its’ buildings. Looking at Art Deco Style Eric Gill – Frieze in Midland Art work - Generate imaginative ideas in response to stimuli - Make connections and see relationships . -

BBC 4 Listings for 15 – 21 December 2018 Page 1 of 4

BBC 4 Listings for 15 – 21 December 2018 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 15 DECEMBER 2018 This film examines the latest scientific and archaeological imagination of Victorian Britain. Santa Claus, Christmas cards evidence to reveal a compelling new narrative, one that sees the and crackers were invented around the same time, but it was SAT 19:00 Britain's Lost Waterlands: Escape to Swallows famous statues as only part of a complex culture that thrived in Dickens's book that boosted the craze for Christmas, above all and Amazons Country (b07k18jf) isolation. Cooper finds a path between competing theories promoting the idea that Christmas is best celebrated with the Documentary which follows presenters Dick Strawbridge and about what happened to Easter Island to make us see this unique family. Alice Roberts as they explore the spectacular British landscapes place in a fresh light. that inspired children's author Arthur Ransome to write his Interviewees include former on-screen Scrooge, Patrick series Swallows and Amazons. Stewart, and writer Lucinda Hawksley, great-great-great- SAT 23:50 Top of the Pops (m0001jgn) granddaughter of Charles Dickens himself. The landscapes he depicted are based on three iconic British Peter Powell and Steve Wright present the pop chart waterlands. The beauty and drama of the Lake District shaped programme, first broadcast on 6 November 1986. Featuring by ancient glaciers and rich in wildlife and natural resources, Bon Jovi, Peter Gabriel and Kate Bush, Red Box, Swing out SUN 22:00 A Christmas Carol (m0001kwg) the shallow man-made waterways of the Norfolk broads so Sister, Duran Duran, Berlin and The Pretenders. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

Daily Mail Online

17/10/2019 A study may claim 1978 was Britain's unhappiest year, but ROGER LEWIS says 'what rot' | Daily Mail Online Privacy Policy Feedback Thursday, Oct 17th 2019 9AM 13°C 12PM 13°C 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel DailyMailTV Discounts Login Nineteen seventy GREAT! A study may Site Web Enter your search claim 1978 was Britain's unhappiest Like Follow Daily Mail Daily Mail year, but ROGER LEWIS says 'what rot' Follow Follow @DailyMail Daily Mail as he remembers Brucie on the box Follow Follow and seven-pint tins of beer @MailOnline Daily Mail By ROGER LEWIS FOR THE DAILY MAIL PUBLISHED: 22:20, 16 October 2019 | UPDATED: 23:15, 16 October 2019 51 486 shares View comments What strikes me is how innocent it all was. If we drank Mateus Rose, the bottles were turned into lampshades. DON'T MISS Few ventured far for their holidays. Weymouth, Margate and Bridlington had yet to Ryan Reynolds shares be eclipsed by the Balearics. first snap of his third child with Blake Lively in sweet family photo... Eating out meant scampi and chips in a basket, an egg burger at a Wimpy with the and seemingly reveals squeezy, tomato-shaped ketchup dispenser and somehow cake tasted different baby's gender So happy when it was called Black Forest Gateau at a Berni Inn. Strictly's Kelvin I’m talking, of course, about 1978, the year a new study tells us was the most Fletcher reveals 12-hour dance rehearsals, 5am miserable for two centuries.