The Seaside Resorts of Westmorland and Lancashire North of the Sands in the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABBOT HALL HOTEL KENTS BANK • GRANGE-OVER-SANDS • LA11 7BG ABBOT HALL HOTEL Kents Bank • Grange-Over-Sands • LA11 7BG

ABBOT HALL HOTEL KENTS BANK • GRANGE-OVER-SANDS • LA11 7BG ABBOT HALL HOTEL Kents Bank • Grange-Over-Sands • LA11 7BG Windermere 17 miles, Kendal 16 miles, Lancaster 29 miles (all distances are approximate) A popular, well established hotel which accommodates up to 121 guests, located in the south of Cumbria • 36 bedrooms in the main house • 14 bedrooms in a bungalow • 2 bedroom cottage • 3 bedroom manager’s cottage • 5 separate lodges providing 11 bedrooms • Coffee shop/bistro • 5 conference rooms with a total capacity of 110 delegates • Leisure facilities including an indoor swimming pool, tennis court, croquet and putting greens • Parking for 45 cars ABBOT HALL HOTEL Abbot Hall is situated in the popular village of Kents Bank, approximately 2 miles from Grange-over-Sands, in the south of Cumbria, overlooking Morecambe Bay. It is understood the land that Abbot Hall occupies was once the site of a religious convent, built by the monks of Furness Abbey in the early 12th century. The present structure was built in 1840 and has been used for a variety of uses since this time, including a family mansion, a school and most recently, a hotel. The Hotel benefits from good access to the A590, which is within easy access of Lake Windermere, approximately 8 miles north and the M6 approximately 15.0 miles north east. Kents Bank railway station is postioned adjacent to the hotel. The station provides direct access to the wider Lake District area as well as Preston, Carlisle, Lancaster and Manchester. CUMBRIA Cumbria is one of the largest and most rural counties in England, famous for its idyllic landscape and the country’s largest national park, the Lake District. -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

COMMUNICATIONS in CUMBRIA : an Overview

Cumbria County History Trust (Database component of the Victoria Country History Project) About the County COMMUNICATIONS IN CUMBRIA : An overview Eric Apperley October 2019 The theme of this article is to record the developing means by which the residents of Cumbria could make contact with others outside their immediate community with increasing facility, speed and comfort. PART 1: Up to the 20th century, with some overlap where inventions in the late 19thC did not really take off until the 20thC 1. ANCIENT TRACKWAYS It is quite possible that many of the roads or tracks of today had their origins many thousands of years ago, but the physical evidence to prove that is virtually non-existent. The term ‘trackway’ refers to a linear route which has been marked on the ground surface over time by the passage of traffic. A ‘road’, on the other hand, is a route which has been deliberately engineered. Only when routes were engineered – as was the norm in Roman times, but only when difficult terrain demanded it in other periods of history – is there evidence on the ground. It was only much later that routes were mapped and recorded in detail, for example as part of a submission to establish a Turnpike Trust.11, 12 From the earliest times when humans settled and became farmers, it is likely that there was contact between adjacent settlements, for trade or barter, finding spouses and for occasional ritual event (e.g stone axes - it seems likely that the axes made in Langdale would be transported along known ridge routes towards their destination, keeping to the high ground as much as possible [at that time (3000-1500BC) much of the land up to 2000ft was forested]. -

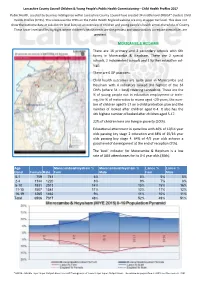

MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There Are 16 Primary and 2 Secondary

Lancashire County Council Children & Young People’s Public Health Commissioning—Child Health Profiles 2017 Public Health, assisted by Business Intelligence within Lancashire County Council have created 34 middle level (MSOA* cluster) Child Health Profiles (CHPs). This is because the CHPs on the Public Health England website are only at upper tier level. This does not show the outcome data at sub-district level but just an overview of children and young people’s health across the whole of County. These lower level profiles highlight where children’s health needs are the greatest and opportunities to reduce inequalities are greatest. MORECAMBE & HEYSHAM There are 16 primary and 2 secondary schools with 6th forms in Morecambe & Heysham. There are 2 special schools, 2 independent schools and 1 further education col- lege. There are 6 GP practices. Child health outcomes are quite poor in Morecambe and Heysham with 4 indicators ranked 3rd highest of the 34 CHPs (where 34 = best) covering Lancashire. These are the % of young people not in education employment or train- ing, the % of maternities to mums aged <20 years, the num- ber of children aged 5-17 on a child protection plan and the number of looked after children aged 0-4. It also has the 4th highest number of looked after children aged 5-17. 22% of children here are living in poverty (10th). Educational attainment in quite low with 46% of 10/11 year olds passing key stage 2 education and 48% of 15/16 year olds passing key stage 4. 64% of 4/5 year olds achieve a good level of development at the end of reception (7th). -

The List of Pharmacies Registered to Sell Ppcs on Our Behalf Is Sorted Alphabetically in Postcode Order

The list of pharmacies registered to sell PPCs on our behalf is sorted alphabetically in postcode order. 0 NAME PREMISES ADDRESS 1 PREMISES ADDRESS 2 PREMISES ADDRESS 3 PREMISES ADDRESS 4 LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, EVERARD CLOSE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 2QU BOOTS UK LIMITED 9 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3DH FREEMAN GRIEVES LTD 111-113 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3ET LLOYDS PHARMACY PARKBURY HOUSE ST PETER ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3HD IMED PHARMACY 67 HATFIELD ROAD ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 4JE LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, BARNET ROAD LONDON COLNEY ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL2 1AB LLOYDS PHARMACY 17 RUSSELL AVENUE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 5ES CROWN PHAMRACY 65 HIGH STREET REDBOURN ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 7LW MANOR PHARMACY (WHEATHAMPSTEAD) LTD 2 HIGH STREET WHEATHAMPSTEAD HERTFORDSHIRE AL4 8AA BOOTS UK LIMITED 23-25 HIGH STREET HARPENDEN HERTFORDSHIRE AL5 2RU LLOYDS PHARMACY 40 HIGH STREET WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL6 9EQ LLOYDS PHARMACY 84 HALDENS WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 1DD BOOTS UK LIMITED 65 MOORS WALK WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 2BQ BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 COLE GREEN LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3PP PEARTREE PHARMACY 110 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3UJ BOOTS UK LIMITED 126 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3XY BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 THE HOWARD CENTRE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL8 6HA LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, CHURCH ROAD WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL8 6SA LLOYDS PHARMACY 9 SHOPLANDS WELWYN GARDEN -

William Maxwell

Descendants of William Maxwell Generation 1 1. WILLIAM1 MAXWELL was born in 1754 in England. He died in Apr 1824 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England. He married Letitia "Letty" Emmerson, daughter of John Emmerson and Mary Simson, on Aug 29, 1785 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England. She was born in 1766 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England. She died on Apr 16, 1848 in Hawksdale, Cumberland, England1. William Maxwell was buried on Apr 19, 1824 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England. William Maxwell and Letitia "Letty" Emmerson had the following children: 2. i. SARAH2 MAXWELL was born in 1800 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England (Parkhead). She died on Jul 08, 1844 in Penrith, Cumberland, England (Cockrey2). She met (1) JOHN PEEL. He was born in 1777 in Greenrigg, Cumberland, England (Caldbeck). He died on Nov 13, 1854 in Ruthwaite, Ireby High, Cumberland, England3-4. She married (2) THOMAS NOBLE on May 22, 1834 in Penrith, Cumberland, England (St. Andrew's Church). He was born about 1795. He died in Oct 1836 in Penrith, Cumberland, England. She married (3) JOHN COPLEY in 1840 in Penrith, Cumberland, England. He was born about 1790 in Buriton, Westmorland, England. He died in 1873 in Penrith, Cumberland, England. 3. ii. MARY MAXWELL was born in 1785 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England (Hartrigg). She married WILLIAM RUTHERFORD. iii. ROBERT MAXWELL was born in 1787 in Dacre, Cumberland, England. iv. JOHN MAXWELL was born in 1788 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England (Hartrigg). v. WILLIAM MAXWELL was born in 1791 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England (Small lands). He died in 1872 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England. He married Hannah Bulman, daughter of Chris Bulman and Ann Foster, on Feb 10, 1842 in Sebergham, Cumberland, England. -

Flookburgh - Cark Travellers Choice 531 / Stagecoach 530 É

Grange - Kents Bank - Flookburgh - Cark Travellers Choice 531 / Stagecoach 530 é Monday to Fridays only Sch Hol Sch Hol 530 531 531 531 530 530 531 Grange, Rail Station - - 11:08 13:18 14:02 - 15:35 Grange Post Office - - 11:12 13:22 14:06 - 15:39 Kents Bank Station - - 11:18 13:28 14:14 - 15:45 Allithwaite Lane End - - R R 14:20 - R Allithwaite Yakkers - - 11:24 13:34 14:22 - 15:51 Flookburgh, Hope & Anchor - - 11:32 13:42 14:26 - 15:59 Ravenstown - - q 13:45 ê - 16:02 Cark, Bank Top Close - - 11:35 13:50 14:29 C - 16:07 Cark, Bank Top Close 09:35 09:30 11:37 13:50 - 14:40 16:07 Ravenstown ê 09:34 11:41 p - ê p Lakeland Leisure Park ê 09:41 11:48 13:58 - ê 16:15 Flookburgh, Hope & Anchor 09:39 09:47 11:54 14:04 - 14:44 16:21 Allithwaite Lane End 09:48 09:53 12:00 ê - 14:53 16:27 Allithwaite Yakkers 09:49 09:55 12:02 14:10 - 14:54 16:29 Kents Bank, Station 09:54 10:00 12:08 ê - 14:59 16:34 Grange St Pauls Church 10:04 10:08 12:16 14:16 - 15:09 16:42 Grange Rail Station 10:07K 10:10 12:18 14:18 - 15:12K 16:44 Grange - Higher Grange - Cartmel Travellers Choice 532 / Stagecoach 530 é Monday to Fridays only Sch Hol Sch Hol Sch Hol 530 530 532 532 530 532 530 532 Grange, Rail Station 09:12 - 10:40 12:48 14:02 14:18 - 14:48 Grange Post Office 09:16 - 10:44 12:52 14:06 14:22 - 14:52 Higher Grange ê - 10:46 12:54 ê 14:24 - 14:54 Cartmel, Clogger Beck 09:28 09:30 10:55 13:05 14:35 14:35 14:35 15:05 Higher Grange - ê 11:00 13:10 - 14:40 ê 15:10 Grange St Paul’s Church - 10:04 11:03 13:13 - 14:43 15:09 15:13 Grange, Rail Station - 10:07K 11:05 13:15 -

Peat Database Results Lancashire

Bare, Lancashire Record ID 236 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 443 649 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat layer (often <1 m thick, hard, consolidated, dry, laminated deposit). Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Boreholes SD46 SW/52-54 Depth of deposit 14C ages available -10 m OD No Notes Bibliographic reference Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. 1998 'Geology of the country around Lancaster', Memoir for 1:50,000 geological sheet 59 (England and Wales), . Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 31 Bare, Lancashire Record ID 237 Authors Year Crofton, A. 1876 Location description Deposit location SD 445 651 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Peat horizon resting on blue organic clay. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available No Notes Crofton (1876) referred to in Brandon et al (1998). Possibly same layer as mentioned by Reade (1904). Bibliographic reference Crofton, A. 1876 'Drift, peat etc. of Heysman [Heysham], Morecambe Bay', Transactions of the Manchester Geological Society, 14, 152-154. Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 2 of 31 Carnforth coastal area, Lancashire Record ID 245 Authors Year Brandon, A., Aitkenhead, N., Crofts, R., 1998 Ellison, R., Evans, D. and Riley, N. Location description Deposit location SD 4879 6987 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Coastal peat up to 4.9 m thick. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Borehole SD 46 NE/1 Depth of deposit 14C ages available Varying from near-surface to at-surface. -

Preliminary Ecological Appraisal Slyne-With-Hest, Lancaster

LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION – SLYNE-WITH-HEST PRELIMINARY ECOLOGICAL APPRAISAL SLYNE-WITH-HEST, LANCASTER Provided for: Lancaster City Council Date: February 2016 Provided by: The Greater Manchester Ecology Unit Clarence Arcade Stamford Street Ashton-under-Lyne Tameside OL6 7PT Tel: 0161 342 4409 LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST QUALITY ASSURANCE Author Suzanne Waymont CIEEM Checked By Stephen Atkins Approved By Derek Richardson Version 1.0 Draft for Comment Reference LSA - 4 The survey was carried out in accordance with the Phase 1 habitat assessment methods (JNCC 2010) and Guidelines for Preliminary Ecological Appraisal (CIEEM 2013). All works associated with this report have been undertaken in accordance with the Code of Professional Conduct for the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management. (www.cieem.org.uk) LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST CONTENTS SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 SURVEY BRIEF 1.2 SITE LOCATION & PROPOSAL 1.3 PERSONNEL 2 LEGISLATION AND POLICY 3 METHODOLOGY 3.1 DESK STUDY 3.2 FIELD SURVEY 3.3 SURVEY LIMITATIONS 4 BASELINE ECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS 4.1 DESKTOP SEARCH 4.2 SURVEY RESULTS 5 ECOLOGICAL CONSTRAINTS – IMPLICATIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS 6 CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES APPENDIX 1 – DATA SEARCH RESULTS APPENDIX 2 – DESIGNATED SITES APPENDIX 3 – BIOLOGICAL HERITAGE SITES LSA – 4 FEBRUARY 2016 LANCASTER SITE ALLOCATION - SLYNE-WITH-HEST SUMMARY • A Preliminary Ecological Appraisal was commissioned by Lancaster City Council to identify possible ecological constraints that could affect the development of 8 sites and areas currently being considered as new site allocations under its Local Plan. This report looks at one of these sites: Slyne-with-Hest. -

Jubilee Digest Briefing Note for Cartmel and Furness

Furness Peninsula Department of History, Lancaster University Victoria County History: Cumbria Project ‘Jubilee Digests’ Briefing Note for Furness Peninsula In celebration of the Diamond Jubilee in 2012, the Queen has decided to re-dedicate the VCH. To mark this occasion, we aim to have produced a set of historical data for every community in Cumbria by the end of 2012. These summaries, which we are calling ‘Jubilee Digests’, will be posted on the Cumbria County History Trust’s website where they will form an important resource as a quick reference guide for all interested in the county’s history. We hope that all VCH volunteers will wish to get involved and to contribute to this. What we need volunteers to do is gather a set of historical facts for each of the places for which separate VCH articles will eventually be written: that’s around 315 parishes/townships in Cumberland and Westmorland, a further 30 in Furness and Cartmel, together with three more for Sedbergh, Garsdale and Dent. The data included in the digests, which will be essential to writing future VCH parish/township articles, will be gathered from a limited set of specified sources. In this way, the Digests will build on the substantial progress volunteers have already made during 2011 in gathering specific information about institutions in parishes and townships throughout Cumberland and Westmorland. As with all VCH work, high standards of accuracy and systematic research are vital. Each ‘Jubilee Digest’ will contain the following and will cover a community’s history from the earliest times to the present day: Name of place: status (i.e. -

Carlisle - Barrow - Lancaster, and Windermere - Lancaster Sunday from 10 May

Carlisle - Barrow - Lancaster, and Windermere - Lancaster Sunday from 10 May A bus A A bus A bus A Carlisle d - - - - - - - - - - Dalston - - - - - - - - - - Wigton - - - - - - - - - - Aspatria - - - - - - - - - - Maryport - - - - - - - - - - Flimby - - - - - - - - - - Workington - 0915 - - - 1015 - 1115 - - Harrington - 0925 - - - 1025 - 1125 - - Parton - 0935 - - - 1035 - 1135 - - Whitehaven a - 0940 - - - 1040 - 1140 - - Whitehaven d - - - - - - - - 1147 - Corkickle - - - - - - - - 1149 - St. Bees - - - - - - - - 1155 - Nethertown - - - - - - - - 11x59 - Braystones - - - - - - - - 12x01 - Sellafield a - - - - - - - - 1207 - d - - - - - - - - 1207 - Seascale - - - - - - - - 1211 - Drigg - - - - - - - - 12x14 - Ravenglass - - - - - - - - 1217 - Bootle (Cumbria) - - - - - - - - 12x23 - Silecroft - - - - - - - - 12x29 - Millom a - - - - - - - - 1236 - Millom d - - - 1036 - - - - 1236 - Green Road - - - 10x40 - - - - 12x40 - Foxfield - - - 1044 - - - - 1244 - Kirkby-in-Furness - - - 10x48 - - - - 12x48 - Askam - - - 1053 - - - - 1253 - Barrow-in-Furness a - - - 1108 - - - - 1308 - Barrow-in-Furness d 0947 - - - 1137 - - - - 1347 Roose 0951 - - - 1141 - - - - 1351 Dalton 0957 - - - 1147 - - - - 1357 Ulverston 1005 - - - 1156 - - - - 1405 Cark 1013 - - - 1203 - - - - 1413 Kents Bank 1017 - - - 1207 - - - - 1417 Grange-over-Sands 1021 - - - 1211 - - - - 1421 Arnside 1027 - - - 1217 - - - - 1427 Silverdale 1031 - - - 1222 - - - - 1431 Windermere d - - 1118 - - - 1308 - - - Staveley - - - - - - 1314 - - - Burneside - - - - - - 1319 - - - Kendal -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 .