A Catalyst for the Development of Human Rights: German Internment Practices in the First World War, 1914-1929

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring of Pseudorabies in Wild Boar of Germany—A Spatiotemporal Analysis

pathogens Article Monitoring of Pseudorabies in Wild Boar of Germany—A Spatiotemporal Analysis Nicolai Denzin 1, Franz J. Conraths 1 , Thomas C. Mettenleiter 2 , Conrad M. Freuling 3 and Thomas Müller 3,* 1 Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Institute of Epidemiology, 17493 Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany; Nicolai.Denzin@fli.de (N.D.); Franz.Conraths@fli.de (F.J.C.) 2 Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, 17493 Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany; Thomas.Mettenleiter@fli.de 3 Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Institute of Molecular Virology and Cell Biology, 17493 Greifswald-Insel Riems, Germany; Conrad.Freuling@fli.de * Correspondence: Thomas.Mueller@fli.de; Tel.: +49-38351-71659 Received: 16 March 2020; Accepted: 8 April 2020; Published: 10 April 2020 Abstract: To evaluate recent developments regarding the epidemiological situation of pseudorabies virus (PRV) infections in wild boar populations in Germany, nationwide serological monitoring was conducted between 2010 and 2015. During this period, a total of 108,748 sera from wild boars were tested for the presence of PRV-specific antibodies using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. The overall PRV seroprevalence was estimated at 12.09% for Germany. A significant increase in seroprevalence was observed in recent years indicating both a further spatial spread and strong disease dynamics. For spatiotemporal analysis, data from 1985 to 2009 from previous studies were incorporated. The analysis revealed that PRV infections in wild boar were endemic in all German federal states; the affected area covers at least 48.5% of the German territory. There were marked differences in seroprevalence at district levels as well as in the relative risk (RR) of infection of wild boar throughout Germany. -

Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (Circa 1850–1945)

BRGÖ 2016 Beiträge zur Rechtsgeschichte Österreichs Martin MOLL, Graz Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (circa 1850–1945) Military jurisdiction in Austria, ca. 1850–1945 This article starts around 1850, a period which saw a new codification of civil and military penal law with a more precise separation of these areas. Crimes committed by soldiers were now defined parallel to civilian ones. However, soldiers were still tried before military courts. The military penal code comprised genuine military crimes like deser- tion and mutiny. Up to 1912 the procedure law had been archaic as it did not distinguish between the state prosecu- tor and the judge. But in 1912 the legislature passed a modern military procedure law which came into practice only weeks before the outbreak of World War I, during which millions of trials took place, conducted against civilians as well as soldiers. This article outlines the structure of military courts in Austria-Hungary, ranging from courts responsible for a single garrison up to the Highest Military Court in Vienna. When Austria became a republic in November 1918, military jurisdiction was abolished. The authoritarian government of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß reintroduced martial law in late 1933; it was mainly used against Social Democrats who staged the February 1934 uprising. After the National Socialist ‘July putsch’ of 1934 a military court punished the rioters. Following Aus- tria’s annexation to Germany in 1938, German military law was introduced in Austria. After the war’s end in 1945, these Nazi remnants were abolished, leaving Austria without any military jurisdiction. Keywords: Austria – Austria as part of Hitler’s Germany –First Republic – Habsburg Monarchy – Military Jurisdiction Einleitung und Themenübersicht allen Staaten gab es eine eigene, von der zivilen Justiz getrennte Strafgerichtsbarkeit des Militärs. -

Area Deprivation and Regional Disparities in Treatment And

Diabetes Care Volume 41, December 2018 2517 Marie Auzanneau,1,2 Stefanie Lanzinger,1,2 Area Deprivation and Regional Barbara Bohn,1,2 Peter Kroschwald,3 Ursula Kuhnle-Krahl,4 Disparities in Treatment and Paul Martin Holterhus,5 Kerstin Placzek,6 Johannes Hamann,7 Rainer Bachran,8 Outcome Quality of 29,284 Joachim Rosenbauer,2,9 and Werner Maier,2,10 on behalf of the Pediatric Patients With Type 1 DPV Initiative Diabetes in Germany: A Cross- sectional Multicenter DPV EPIDEMIOLOGY/HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH Analysis Diabetes Care 2018;41:2517–2525 | https://doi.org/10.2337/dc18-0724 1Institute of Epidemiology and Medical Biome- try, ZIBMT, University of Ulm, Ulm, Germany 2German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD), Neuherberg, Germany 3Children’s Hospital, Ruppiner Kliniken GmbH, OBJECTIVE Hochschulklinikum der Medizinischen Hochschule This study analyzed whether area deprivation is associated with disparities in health Brandenburg, Neuruppin, Germany 4 care of pediatric type 1 diabetes in Germany. Practice for Pediatric Endocrinology and Dia- betology, Gauting, Germany 5 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS Division of Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabe- tes, Department of Pediatrics, University Hospital We selected patients <20 years of age with type 1 diabetes and German residence of Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Kiel/Christian- documented in the “diabetes patient follow-up” (Diabetes-Patienten-Verlaufsdo- Albrechts University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany 6 kumentation [DPV]) registry for 2015/2016. Area deprivation was assessed by Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, University Hospital, Martin-Luther University, Halle, Germany quintiles of the German Index of MultipleDeprivation (GIMD 2010) at the district level 7Department of Pediatrics, St. Marien Hospital and was assigned to patients. -

The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders

xv The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders 30 Revue De Droit Militaire Et De Droit De LA Guerre 183 (1991) Introduction s long as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs of A war, more popularly known as "war crimes trials", the trial tribunals have been confronted with the defense of "superior orders"-the claim that the accused did what he did because he was ordered to do so by a superior officer (or by his Government) and that his refusal to obey the order would have brought dire consequences upon him. And as along as there have been trials for violations of the laws and customs ofwar the trial tribunals have almost uniformly rejected that defense. However, since the termination of the major programs of war crimes trials conducted after World War II there has been an ongoing dispute as to whether a plea of superior orders should be allowed, or disallowed, and, if allowed, the criteria to be used as the basis for its application. Does international action in this area constitute an invasion of the national jurisdiction? Should the doctrine apply to all war crimes or only to certain specifically named crimes? Should the illegality of the order received be such that any "reasonable" person would recognize its invalidity; or should it be such as to be recognized by a person of"ordinary sense and understanding"; or by a person ofthe "commonest understanding"? Should it be "illegal on its face"; or "manifesdy illegal"; or "palpably illegal"; or of "obvious criminality,,?1 An inability to reach a generally acceptable consensus on these problems has resulted in the repeated rejection of attempts to legislate internationally in this area. -

The Impact of Changing Youth Employment Patterns on Future Wages

| January 31, 2014| THE IMPACT OF CHANGING YOUTH EMPLOYMENT PATTERNS ON FUTURE WAGES Matthias Umkehrer1 This paper examines employment patterns on the labor market for youth and changing returns to early-career employment stability over the past four decades. German administrative matched employer-employee data allow to contrast the ca- reers of German males who graduated from the Dual Education System in West Germany between the years 1977 and 2001. True state dependence is separated from unobserved heterogeneity by utilizing within-cohort variation in aggregate economic conditions prevailing at different stages of the early-career cycle as an instrument for stability. The results indicate decreasing stability of employment since the late 1980s, limited to the lower half of the employment distribution. Stable employment early in professional life, however, is found to have significant positive wage returns, particularly for low wage earners. These returns have substantially increased between the late 1970s and the late 1990s, again especially for low wage earners. Keywords: Youth employment, Returns to employment stability, True state de- pendence, Quantile instrumental variable regression JEL-Classification: C20, J21, J31. 1. INTRODUCTION In light of the alarming employment situation for young workers in many in- dustrialized economies, there has been a renewed interest in the labor market conditions for youth. In April 2013, the Council of the European Union has recommended to establish a Youth Guarantee to \ensure that all young peo- ple under the age of 25 years receive a good-quality offer of employment [...] within a period of four months of becoming unemployed or leaving formal ed- ucation." European Union(2013, p. -

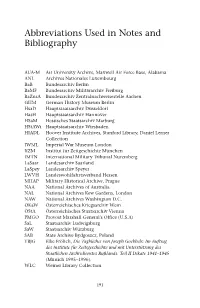

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Protection of Minorities in Upper Silesia

[Distributed to the Council.] Official No. : C-422. I 932 - I- Geneva, May 30th, 1932. LEAGUE OF NATIONS PROTECTION OF MINORITIES IN UPPER SILESIA PETITION FROM THE “ASSOCIATION OF POLES IN GERMANY”, SECTION I, OF OPPELN, CONCERNING THE SITUATION OF THE POLISH MINORITY IN GERMAN UPPER SILESIA Note by the Secretary-General. In accordance with the procedure established for petitions addressed to the Council of the League of Nations under Article 147 of the Germano-Polish Convention of May 15th, 1922, concerning Upper Silesia, the Secretary-General forwarded this petition with twenty appendices, on December 21st, 1931, to the German Government for its observations. A fter having obtained from the Acting-President of the Council an extension of the time limit fixed for the presentation of its observations, the German Government forwarded them in a letter dated March 30th, 1932, accompanied by twenty-nine appendices. The Secretary-General has the honour to circulate, for the consideration of the Council, the petition and the observations of the German Government with their respective appendices. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page I Petition from the “Association of Poles in Germany”, Section I, of Oppeln, con cerning the Situation of the Polish Minority in German Upper Silesia . 5 A ppendices to th e P e t i t i o n ................................................................................................................... 20 II. O bservations of th e G erm an G o v e r n m e n t.................................................................................... 9^ A ppendices to th e O b s e r v a t i o n s ...............................................................................................................I03 S. A N. 400 (F.) 230 (A.) 5/32. -

The Economic Productivity at the German Coast

The economic productivity at the German coast North Sea Elbe Baltic Sea 100000 100000 100000 Hamburg Hamburg Schleswig-Holstein 90000 Schleswig-Holstein 90000 Schleswig-Holstein 90000 Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Lower Saxony Bremen Lower-Saxony 80000 80000 80000 70000 70000 70000 60000 60000 60000 50000 50000 50000 40000 40000 40000 30000 30000 30000 20000 20000 20000 10000 10000 10000 0 0 0 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 year year year Authoress: C. Hagner ISSN 0344-9629 GKSS 2003/14 GKSS 2003/14 The economic productivity at the German coast Authoress: C. Hagner (Institute for Coastal Research) GKSS-Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH • Geesthacht • 2003 Die Berichte der GKSS werden kostenlos abgegeben. The delivery of the GKSS reports is free of charge. Anforderungen/Requests: GKSS-Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH Bibliothek/Library Postfach 11 60 D-21494 Geesthacht Germany Fax.: (49) 04152/871717 Als Manuskript vervielfältigt. Für diesen Bericht behalten wir uns alle Rechte vor. ISSN 0344-9629 GKSS-Forschungszentrum Geesthacht GmbH • Telefon (04152)87-0 Max-Planck-Straße • D-21502 Geesthacht / Postfach 11 60 • D-21494 Geesthacht GKSS 2003/14 The economic productivity at the German coast Charlotte Hagner 33 pages with 6 figures and 15 tables Abstract In this report the economic productivity of the German coast is compared to selected inland areas. The analysis is based on administrative district data over the period 1991–2000. As economic indicators the total gross added value in the economy as a whole, per person in employment and the gross added value in four different sectors are chosen. -

Downloaded for Personal Non-Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Hobbs, Mark (2010) Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2182/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Visual representations of working-class Berlin, 1924–1930 Mark Hobbs BA (Hons), MA Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of PhD Department of History of Art Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow February 2010 Abstract This thesis examines the urban topography of Berlin’s working-class districts, as seen in the art, architecture and other images produced in the city between 1924 and 1930. During the 1920s, Berlin flourished as centre of modern culture. Yet this flourishing did not exist exclusively amongst the intellectual elites that occupied the city centre and affluent western suburbs. It also extended into the proletarian districts to the north and east of the city. Within these areas existed a complex urban landscape that was rich with cultural tradition and artistic expression. This thesis seeks to redress the bias towards the centre of Berlin and its recognised cultural currents, by exploring the art and architecture found in the city’s working-class districts. -

BAOR July 1989

BAOR ORDER OF BATTLE JULY 1989 “But Pardon, and Gentles all, The flat unraised spirits that have dared On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth So great an object….” Chorus, Henry V Act 1, Prologue This document began over five years ago from my frustration in the lack of information (or just plain wrong information) regarding the British Army of The Rhine in general and the late Cold War in particular. The more I researched through books, correspondence, and through direct questions to several “Old & Bold” on Regimental Association Forums, the more I became determined to fill in this gap. The results are what you see in the following pages. Before I begin a list of acknowledgements let me recognize my two co-authors, for this is as much their work as well as mine. “PM” was instrumental in sharing his research on the support Corps, did countless hours of legwork, and never failed to dig up information on some of my arcane questions. “John” made me “THINK” British Army! He has been an inspiration; a large part of this work would have not been possible without him. He added the maps and the color formation signs, as well as reformatting the whole document. I can only humbly say that these two gentlemen deserve any and all accolades as a result of this document. Though we have put much work into this document it is far from finished. Anyone who would like to contribute information of their time in BAOR or sources please contact me at [email protected]. The document will be updated with new information periodically. -

Military Ranks

WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 ABSTRACT WHO WILL SERVE? EDUCATION, LABOR MARKETS, AND MILITARY PERSONNEL POLICY by Lindsay P. Cohn Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Peter D. Feaver, Supervisor ___________________________ David Soskice ___________________________ Christopher Gelpi ___________________________ Tim Büthe ___________________________ Alexander B. Downes An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2007 Copyright by Lindsay P. Cohn 2007 Abstract Contemporary militaries depend on volunteer soldiers capable of dealing with advanced technology and complex missions. An important factor in the successful recruiting, retention, and employment of quality personnel is the set of personnel policies which a military has in place. It might be assumed that military policies on personnel derive solely from the functional necessities of the organization’s mission, given that the stakes of military effectiveness are generally very high. Unless the survival of the state is in jeopardy, however, it will seek to limit defense costs, which may entail cutting into effectiveness. How a state chooses to make the tradeoffs between effectiveness and economy will be subject to influences other than military necessity. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of a History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) by Thomas M

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) by Thomas M. Lindsay This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A History of the Reformation (Vol. 1 of 2) Author: Thomas M. Lindsay Release Date: August 29, 2012 [Ebook 40615] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HISTORY OF THE REFORMATION (VOL. 1 OF 2)*** International Theological Library A History of The Reformation By Thomas M. Lindsay, M.A., D.D. Principal, The United Free Church College, Glasgow In Two Volumes Volume I The Reformation in Germany From Its Beginning to the Religious Peace of Augsburg Edinburgh T. & T. Clark 1906 Contents Series Advertisement. 2 Dedication. 6 Preface. 7 Book I. On The Eve Of The Reformation. 11 Chapter I. The Papacy. 11 § 1. Claim to Universal Supremacy. 11 § 2. The Temporal Supremacy. 16 § 3. The Spiritual Supremacy. 18 Chapter II. The Political Situation. 29 § 1. The small extent of Christendom. 29 § 2. Consolidation. 30 § 3. England. 31 § 4. France. 33 § 5. Spain. 37 § 6. Germany and Italy. 41 § 7. Italy. 43 § 8. Germany. 46 Chapter III. The Renaissance. 53 § 1. The Transition from the Mediæval to the Modern World. 53 § 2. The Revival of Literature and Art. 56 § 3. Its earlier relation to Christianity. 59 § 4. The Brethren of the Common Lot.