The Rise and Fall of an Internationally Codified Denial of the Defense of Superior Orders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16. the Nuremberg Trials: Nazi Criminals Face Justice

fdr4freedoms 1 16. The Nuremberg Trials: Nazi Criminals Face Justice On a ship off the coast of Newfoundland in August 1941, four months before the United States entered World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill agreed to commit themselves to “the final destruction of Nazi tyranny.” In mid-1944, as the Allied advance toward Germany progressed, another question arose: What to do with the defeated Nazis? FDR asked his War Department for a plan to bring Germany to justice, making it accountable for starting the terrible war and, in its execution, committing a string of ruthless atrocities. By mid-September 1944, FDR had two plans to consider. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr. had unexpectedly presented a proposal to the president two weeks before the War Department finished its own work. The two plans could not have been more different, and a bitter contest of ideas erupted in FDR’s cabinet. To execute or prosecute? Morgenthau proposed executing major Nazi leaders as soon as they were captured, exiling other officers to isolated and barren lands, forcing German prisoners of war to rebuild war-scarred Europe, and, perhaps most controversially, Defendants and their counsel in the trial of major war criminals before the dismantling German industry in the highly developed Ruhr International Military Tribunal, November 22, 1945. The day before, all defendants and Saar regions. One of the world’s most advanced industrial had entered “not guilty” pleas and U.S. top prosecutor Robert H. Jackson had made his opening statement. “Despite the fact that public opinion already condemns economies would be left to subsist on local crops, a state their acts,” said Jackson, “we agree that here [these defendants] must be given that would prevent Germany from acting on any militaristic or a presumption of innocence, and we accept the burden of proving criminal acts and the responsibility of these defendants for their commission.” Harvard Law School expansionist impulses. -

Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context

Goettingen Journal of International Law 2 (2010) 3, 871-892 Defending the Emergence of the Superior Orders Defense in the Contemporary Context Jessica Liang Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 872 A. Introduction .......................................................................................... 872 B. Superior Orders and the Soldier‘s Dilemma ........................................ 872 C. A Brief History of the Superior Orders Defense under International Law ............................................................................................. 874 D. Alternative Degrees of Attributing Criminal Responsibility: Finding the Right Solution to the Soldier‘s Dilemma ..................................... 878 I. Absolute Defense ................................................................................. 878 II. Absolute Liability................................................................................. 880 III.Conditional Liability ............................................................................ 881 1. Manifest Illegality ..................................................................... 881 2. A Reasonableness Standard ...................................................... 885 E. Frontiers of the Defense: Obedience to Civilian Orders? .................... 889 I. Operation under the Rome Statute ....................................................... 889 II. How far should the Defense of Superior Orders -

Excerpt from Elizabeth Borgwardt, the Nuremberg Idea: “Thinking Humanity” in History, Law & Politics, Under Contract with Alfred A

Excerpt from Elizabeth Borgwardt, The Nuremberg Idea: “Thinking Humanity” in History, Law & Politics, under contract with Alfred A. Knopf. DRAFT of 10/24/16; please do not cite or quote without author’s permission Human Rights Workshop, Schell Center for International Human Rights, Yale Law School November 3, 2016, 12:10 to 1:45 pm, Faculty Lounge Author’s Note: Thank you in advance for any attention you may be able to offer to this chapter in progress, which is approximately 44 double-spaced pages of text. If time is short I recommend starting with the final section, pp. 30-42. I look forward to learning from your reactions and suggestions. Chapter Abstract: This history aims to show how the 1945-49 series of trials in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice distilled the modern idea of “crimes against humanity,” and in the process established the groundwork for the modern international human rights regime. Over the course of the World War II era, a 19th century version of crimes against humanity, which might be rendered more precisely in German as Verbrechen gegen die Menschlichkeit (crimes against “humane-ness”), competed with and was ultimately co-opted by a mid-20th- century conception, translated as Verbrechen gegen die Menschheit (crimes against “human- kind”). Crimes against humaneness – which Hannah Arendt dismissed as “crimes against kindness” – were in effect transgressions against traditional ideas of knightly chivalry, that is, transgressions against the humanity of the perpetrators. Crimes against humankind – the Menschheit version -- by contrast, focused equally on the humanity of victims. Such extreme atrocities most notably denied and attacked the humanity of individual victims (by denying their human rights, or in Arendt’s iconic phrasing, their “right to have rights”). -

Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (Circa 1850–1945)

BRGÖ 2016 Beiträge zur Rechtsgeschichte Österreichs Martin MOLL, Graz Militärgerichtsbarkeit in Österreich (circa 1850–1945) Military jurisdiction in Austria, ca. 1850–1945 This article starts around 1850, a period which saw a new codification of civil and military penal law with a more precise separation of these areas. Crimes committed by soldiers were now defined parallel to civilian ones. However, soldiers were still tried before military courts. The military penal code comprised genuine military crimes like deser- tion and mutiny. Up to 1912 the procedure law had been archaic as it did not distinguish between the state prosecu- tor and the judge. But in 1912 the legislature passed a modern military procedure law which came into practice only weeks before the outbreak of World War I, during which millions of trials took place, conducted against civilians as well as soldiers. This article outlines the structure of military courts in Austria-Hungary, ranging from courts responsible for a single garrison up to the Highest Military Court in Vienna. When Austria became a republic in November 1918, military jurisdiction was abolished. The authoritarian government of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß reintroduced martial law in late 1933; it was mainly used against Social Democrats who staged the February 1934 uprising. After the National Socialist ‘July putsch’ of 1934 a military court punished the rioters. Following Aus- tria’s annexation to Germany in 1938, German military law was introduced in Austria. After the war’s end in 1945, these Nazi remnants were abolished, leaving Austria without any military jurisdiction. Keywords: Austria – Austria as part of Hitler’s Germany –First Republic – Habsburg Monarchy – Military Jurisdiction Einleitung und Themenübersicht allen Staaten gab es eine eigene, von der zivilen Justiz getrennte Strafgerichtsbarkeit des Militärs. -

Nuremberg Icj Timeline 1474-1868

NUREMBERG ICJ TIMELINE 1474-1868 1474 Trial of Peter von Hagenbach In connection with offenses committed while governing ter- ritory in the Upper Alsace region on behalf of the Duke of 1625 Hugo Grotius Publishes On the Law of Burgundy, Peter von Hagenbach is tried and sentenced to death War and Peace by an ad hoc tribunal of twenty-eight judges representing differ- ent local polities. The crimes charged, including murder, mass Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, one of the principal rape and the planned extermination of the citizens of Breisach, founders of international law with such works as Mare Liberum are characterized by the prosecution as “trampling under foot (On the Freedom of the Seas), publishes De Jure Belli ac Pacis the laws of God and man.” Considered history’s first interna- (On the Law of War and Peace). Considered his masterpiece, tional war crimes trial, it is noted for rejecting the defense of the book elucidates and secularizes the topic of just war, includ- superior orders and introducing an embryonic version of crimes ing analysis of belligerent status, adequate grounds for initiating against humanity. war and procedures to be followed in the inception, conduct, and conclusion of war. 1758 Emerich de Vattel Lays Foundation for Formulating Crime of Aggression In his seminal treatise The Law of Nations, Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel alludes to the great guilt of a sovereign who under- 1815 Declaration Relative to the Universal takes an “unjust war” because he is “chargeable with all the Abolition of the Slave Trade evils, all the horrors of the war: all the effusion of blood, the The first international instrument to condemn slavery, the desolation of families, the rapine, the acts of violence, the rav- Declaration Relative to the Universal Abolition of the Slave ages, the conflagrations, are his works and his crimes . -

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court The text of the Rome Statute reproduced herein was originally circulated as document A/CONF.183/9 of 17 July 1998 and corrected by procès-verbaux of 10 November 1998, 12 July 1999, 30 November 1999, 8 May 2000, 17 January 2001 and 16 January 2002. The amendments to article 8 reproduce the text contained in depositary notification C.N.651.2010 Treaties-6, while the amendments regarding articles 8 bis, 15 bis and 15 ter replicate the text contained in depositary notification C.N.651.2010 Treaties-8; both depositary communications are dated 29 November 2010. The table of contents is not part of the text of the Rome Statute adopted by the United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court on 17 July 1998. It has been included in this publication for ease of reference. Done at Rome on 17 July 1998, in force on 1 July 2002, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 2187, No. 38544, Depositary: Secretary-General of the United Nations, http://treaties.un.org. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Published by the International Criminal Court ISBN No. 92-9227-232-2 ICC-PIOS-LT-03-002/15_Eng Copyright © International Criminal Court 2011 All rights reserved International Criminal Court | Po Box 19519 | 2500 CM | The Hague | The Netherlands | www.icc-cpi.int Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Table of Contents PREAMBLE 1 PART 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE COURT 2 Article 1 The Court 2 Article 2 Relationship of the Court with the United Nations 2 Article 3 Seat of the Court 2 Article 4 Legal status and powers of the Court 2 PART 2. -

The Pacific War Crimes Trials: the Importance of the "Small Fry" Vs. the "Big Fish"

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Summer 2012 The aP cific aW r Crimes Trials: The mpI ortance of the "Small Fry" vs. the "Big Fish" Lisa Kelly Pennington Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Pennington, Lisa K.. "The aP cific aW r Crimes Trials: The mporI tance of the "Small Fry" vs. the "Big Fish"" (2012). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/rree-9829 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PACIFIC WAR CRIMES TRIALS: THE IMPORTANCE OF THE "SMALL FRY" VS. THE "BIG FISH by Lisa Kelly Pennington B.A. May 2005, Old Dominion University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2012 Approved by: Maura Hametz (Director) Timothy Orr (Member) UMI Number: 1520410 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Medical War Crimes

Medical War Crimes Sigrid Mehring* A. von Bogdandy and R. Wolfrum, (eds.), Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law, Volume 15, 2011, p. 229-279. © 2011 Koninklijke Brill N.V. Printed in The Netherlands. 230 Max Planck UNYB 15 (2011) I. Introduction II. Medical War Crimes 1. Medical Grave Breaches and Medical War Crimes 2. Medical Aspects of the Classic Grave Breaches III. Medical War Crimes in International Criminal Law 1. The ICTY and ICTR Statutes 2. The Rome Statute IV. National Implementation: The German Example V. The Prosecution of Medical War Crimes 1. The Doctors’ Trial of 1947 2. The Ntakirutimana Trial of 2003 3. General Observations concerning Prosecution VI. Possible Defenses to Medical War Crimes 1. Superior Orders 2. Mistake of Fact 3. Necessity and Duress 4. Consent of the Patient VII. Conclusion Mehring, Medical War Crimes 231 I. Introduction Physicians have always played an important role in armed conflicts be- ing the first to treat wounded and sick combatants, prisoners of war, and civilians. This makes them an important, essential category of ac- tors in armed conflicts, a role which is reflected in the laws of war.1 In granting first aid and emergency care, physicians can fulfill a further role by reporting on human rights abuses or violations of international humanitarian law.2 They are thus in a privileged position to watch over the rights of the victims of armed conflicts. However, their position is also susceptible to abuse. Physicians have always used armed conflicts for their own gain, to further their medical skills or to use their skills to enhance military gains or further medical science. -

Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 46 | Issue 3 Article 4 5-2017 A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg Stephen J. Sfekas Circuit Court for Baltimore City, Maryland Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Fourteenth Amendment Commons, International Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Sfekas, Stephen J. (2017) "A Court Pure and Unsullied: Justice in the Justice Trial at Nuremberg," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 46 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol46/iss3/4 This Peer Reviewed Articles is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COURT PURE AND UNSULLIED: JUSTICE IN THE JUSTICE TRIAL AT NUREMBERG* Hon. Stephen J. Sfekas** Therefore, O Citizens, I bid ye bow In awe to this command, Let no man live Uncurbed by law nor curbed by tyranny . Thus I ordain it now, a [] court Pure and unsullied . .1 I. INTRODUCTION In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the common understanding was that the Nazi regime had been maintained by a combination of instruments of terror, such as the Gestapo, the SS, and concentration camps, combined with a sophisticated propaganda campaign.2 Modern historiography, however, has revealed the -

Clemency in a Nazi War Crimes Trial By: Allison Ernest

Evading the Hangman’s Noose: Clemency in a Nazi War Crimes Trial By: Allison Ernest Ernest 2 Contents Introduction: The Foundations for a War Crimes Trial Program 3 Background and Historiography 10 Chapter 1: Investigations into Other Trials Erode the United States’ Resolve 17 Chapter 2: The Onset of Trial Fatigue Due to Public Outcry 25 Chapter 3: High Commissioner McCloy Authorizes Sentence Reviews 38 Chapter 4: McCloy and the United States Set the War Criminals Free 45 Conclusion: A Lesson to be Learned 52 Chart: A Complicated Timeline Simplified 57 Bibliography 58 Ernest 3 Introduction: The Foundations for a War Crimes Trial Program “There is a supervening affirmative duty to prosecute the doers of serious offenses that falls on those who are empowered to do so on behalf of a civilized community. This duty corresponds to our fundamental rights as citizens and as persons to receive and give respect to each other in view of our possession of such rights.” Such duty, outlined by contemporary philosopher Alan S. Rosenbaum, was no better exemplified than in the case of Nazi war criminals in the aftermath of World War II. Even before the floundering Axis powers of Germany and Japan declared their respective official surrenders in 1945, the leaders of the Allies prepared possible courses of action for the surviving criminals in the inevitable collapse of the Nazi regime. Since the beginning of the war in 1939, the Nazi regime in Germany implemented a policy of waging a war so barbaric in its execution that the total numbers of casualties rivaled whole populations of countries. -

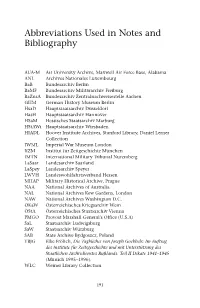

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography

Abbreviations Used in Notes and Bibliography AUA-M Air University Archive, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama ANL Archives Nationales Luxembourg BaB Bundesarchiv Berlin BaMF Bundesarchiv Militärarchiv Freiburg BaZnsA Bundesarchiv Zentralnachweisestelle Aachen GHM German History Museum Berlin HsaD Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf HasH Hauptstaatsarchiv Hannover HSaM Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg HStAWi Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden HIADL Hoover Institute Archives, Stanford Library, Daniel Lerner Collection IWML Imperial War Museum London IfZM Institut für Zeitgeschichte München IMTN International Military Tribunal Nuremberg LaSaar Landesarchiv Saarland LaSpey Landesarchiv Speyer LWVH Landeswohlfahrtsverband Hessen MHAP Military Historical Archive, Prague NAA National Archives of Australia NAL National Archives Kew Gardens, London NAW National Archives Washington D.C. OKaW Österreichisches Kriegsarchiv Wein ÖStA Österreichisches Staatsarchiv Vienna PMGO Provost Marshall General’s Office (U.S.A) SaL Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg SaW Staatsarchiv Würzburg SAB State Archive Bydgoszcz, Poland TBJG Elke Frölich, Die Tagbücher von Joseph Goebbels: Im Auftrag des Institute für Zeitsgeschichte und mit Unterstützung des Staatlichen Archivdienstes Rußlands. Teil II Dikate 1941–1945 (Münich 1995–1996). WLC Weiner Library Collection 191 Notes Introduction: Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear: The Historiography of the Nazi Terror State 1 . Christopher Hutton, Race and the Third Reich: Linguistics, Racial Anthropology and Genetics in the Third Reich (Cambridge 2005), p. 18. 2 . Rosemary O’Kane, Terror, Force and States: The Path from Modernity (Cheltham 1996), p. 19. O’Kane defines a system of terror, as one that is ‘distinguished by summary justice, where the innocence or guilt of the victims is immaterial’. 3 . See Robert Thurston, ‘The Family during the Great Terror 1935–1941’, Soviet Studies , 43, 3 (1991), pp. 553–74. -

Criminalization of Crimes Against Humanity Under National Law

This is a repository copy of Criminalization of Crimes Against Humanity under National Law. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/143059/ Version: Accepted Version Article: van Sliedregt, E orcid.org/0000-0003-1146-0638 (2019) Criminalization of Crimes Against Humanity under National Law. Journal of International Criminal Justice, 16 (4). pp. 729- 749. ISSN 1478-1387 https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqy027 © The Author(s) (2019). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Journal of International Criminal Justice. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ To be published in the Journal of International Criminal Justice, Oxford Journals PLEASE DO NOT CITE The ILC Draft Convention on Crimes Against Humanity - Criminalization under National Law Elies van Sliedregt* Abstract This paper discusses Article 6 of the International Law Commission’s (ILC) draft articles on crimes against humanity, which deals with criminalization of crimes against humanity in national law.