Transmedial Collaborative Productions in Secret Path and Airplane Mode

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

Ohad Benchetrit - Justin Small

Ohad Benchetrit - Justin Small A bit about us, Ohad Benchetrit & Justin Small: As founding members of critically acclaimed Toronto based band Do Make Say Think, we have been creating engaging, epic, and emotional music together for over 23 years. As composers, our focus has always centered around melody, artistic integrity, passion, and spirited experimentation. This has opened the door to a decades long career in film composition. We’ve always picked projects with lots of heart and beauty and believe score to be an integral part of the story telling. To add color, and emotion but not to lead. To add feel but not to persuade. We’ve been honored with multiple awards, including the 2018 JUNO award for best instrumental album with our work with Do Make Say Think, the Best Original Score in 2016 at the LA scream Fest and a Canadian Screen Award in 2012 for Best original score for a documentary for Semi-Sweet: Life in Chocolate We pride ourselves on finding the right emotional tone that both the director and picture are trying to convey. With Ohad's classical training and Justin's minimalist and immediate sense of melody we feel we have created a unique sound and style of film composition that holds the emotional crux of the entire project in the highest order. We love what we do. AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS JUNO AWARDS (2018) STUBBORN PRESISTENT ILLUSIONS Instrumental Album of the Year *As Do Make Say Think SCREAMFEST (2016) MY FATHER DIE Best Musical Score CANADIAN SCREEN AWARD (2012) SEMI-SWEET: LIFE IN CHOCOLATE Best Original Music for a Non-Fiction Program or Series FEATURE FILM THE DAWNSAYER Paul Kell, prod. -

You Can't See Me I Am a Stranger…Do You Know What I Mean?

The Stranger I am a stranger…You can't see me I am a stranger…Do you know what I mean? I navigate the mud…I walk above the path Jumpin' to the right…Then I jump to the left On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path nobody knows And what I'm feelin'…Is anyone's guess What is in my head…And what's in my chest I'm not gonna stop…I'm just catching my breath They're not gonna stop…Please just let me catch my breath I am the stranger…You can't see me I am the stranger…Do you know what I mean? That is not my dad…My dad is not a wild man Doesn't even drink…My dad, he's not a wild man On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path that nobody knows I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… www.downiewenjack.ca Grace, too He said I'm fabulously rich C'mon just let's go She kinda bit her lip Geez, I don't know But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with will and determination And grace, too The secret rules of engagement Are hard to endorse When the appearance of conflict Meets the appearance of force But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with skill and it's frustration And grace, too www.downiewenjack.ca Poets Spring starts when a heartbeat's pounding When the birds can be heard Above the reckoning carts doing some final accounting Lava flowing in Superfarmer’s -

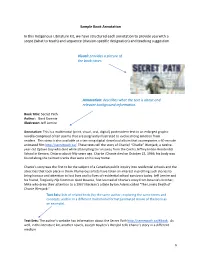

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Talk Into Tune

Talk into tune When Toronto musician Charles Spearin asked his neighbours about happiness, he didn't just listen to their answers - he turned them into songs CARL WILSON From Wednesday's Globe and Mail Published on Tuesday, Feb. 10, 2009 4:45PM EST Last updated on Thursday, Apr. 09, 2009 11:39PM EDT As a piano-trumpet duo skitters around her, a person with a pleasant professional accent talks about her work with “challenged young women” who tell her “all the time” that they're happy. “Some of their expectations are so simplistic – not to say simplicity because they're challenged … ” Then the thought strikes: “It's like they don't ask beyond of what's present.” Immediately the voice repeats: “It's like they don't ask beyond of what's present.” And again: “It's like they don't ask beyond of what's present.” At which point the music makes its own breakthrough. Keyboard and horn link arms with bass and drums and kick out a chorus to the precise tune and tempo of the woman's words. You can almost see her with brass band and challenged charges on parade through New Orleans, fanfaring their be-here-now anthem – sing it, sister! – It's Like They Don't Ask Beyond of What's Present! This is Anna, Track 2 of The Happiness Project, the first solo album by Toronto musician Charles Spearin, which was released yesterday. Actually, solo is a misnomer. A multi-instrumentalist with tight-knit space-rock ensemble Do Make Say Think as well as that legions-strong study in socio-rockology, the popular band Broken Social Scene, Spearin prefers company – in this case, his whole neighbourhood. -

The Cord Weeklythe Tie That Binds Since 1926 CRISIS, WHAT CRISIS? NETWANKING BACK in BLACK

The Cord WeeklyThe tie that binds since 1926 CRISIS, WHAT CRISIS? NETWANKING BACK IN BLACK . Examining_ the growing food crisis af- Facebook or Twitter? Comparing the Attack in Black talk to The Cord be- ... fecting the world PAGE 10 giants of the social web ... PAGE 12 fore their Thursday show ... PAGE 24 Volume 49 Issue 28 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1,2009 www.cordweekly.com Culture Jamming The perfect way to spend April Fool's Day. A feature by Kari Pritchard See pages 14-15 Bus pass Curlers extended golden Laurier students to be granted May-August The women's curling coverage with Grand River Transit service team claimed Laurier's 11th national title last MORGAN ALAN in school full-time, they will still weekend in Montreal STAFF WRITER be granted year-round access. A similar system is currently in place Effective May 1, full-time Laurier at the University ofWaterloo. LUKE DOTTO STAFF undergraduate students will be "The benefit to students is quite WRITER able to ride Grand River Transit high, given the number of students (GRT) buses year-round by show- who will be able to access [the ser- History has a tendency to repeat it- ing their Onecards. vice]," said Colin Le Fevre, WLUSU self for the Golden Hawks women's Previously, student fees only president. curling team. One covered GRT bus use for the aca- The expansion will necessitate year after claiming the first ever Canadian Interuniversity demic year. Students wishing to an increase of roughly 18 percent Associa- use public transit in the summer in the bus fee. -

Northern Cree When It's Cold Cree Round Dance Songs

Charlotte Cornfield The Shape of Your Name “You free yourself when you take away the script,” says Toronto songwriter Charlotte Artist: Charlotte Cornfield Cornfield. “That’s where this record came from, dismantling patterns and embracing Title: The Shape of Your Name the process.” Cornfield’s third full length, The Shape of Your Name, is set to arrive in Genre: Singer-Songwriter, Indie, Folk April 5, 2019 via Outside Music imprint Next Door Records. The album has a more Recommended if you like Phoebe Bridgers, Big Thief, Julien honed studio sound than her scrappier 2016 release Future Snowbird, and for good Baker, Soccer Mommy, boygenius, Lucy Dacus reason: it was recorded in 5 different sessions over the course of 3 years. The songs are her strongest and most striking to date - contemplative and contemporary, funny Release Date: April 5, 2019 and heart-wrenching - and they’ve got that stuck-in-your-head-for-days quality that LP: NDR0001 Cornfield is known for. The Shape of Your Name features a star-studded cast of LP UPC: 623339912617 collaborators including (but not limited to) Grammy-winning engineer 12” Slip Sleeve Shawn Everett (Kurt Vile, Alabama Shakes, Weezer, Julian Casablancas), Broken Social Scene members Brendan Canning, Kevin Drew and Charles Spearin, and Montreal songwriter Leif Vollebekk. “My initial intention wasn’t to make a record at all,” Cornfield muses. “The whole thing CD: 23339-9126-2 kind of happened by accident. I went to The Banff Centre to do a residency and came CD UPC: 623339912624 out with these recordings that I knew I wanted to use for something but wasn’t sure Digipak what.” She brought the unfinished songs to her former roommate Nigel Ward in Montreal. -

CST120 CONSTELLATION Do Make Say Think Stubborn Persistent Illusions

Do Make Say Think Stubborn Persistent Illusions 2x180gLP • CD • DL Release Date: 19 May 2017 “Do Make Say Think legitimize post-rock as a term of art... engender some of the most honest, unpretentious, group-oriented rock of their time." – Popmatters “Experimental rock on the grandest and most impressive of scales with not a trace of musical mildew or corrosion." – The Wire “The supernova in Constellation’s stellar network... arguably the finest back catalogue of any currently operating instrumental rock band." – Drowned In Sound Do Make Say Think has been widely celebrated as one of the preeminent instrumental rock bands of the 90s-00s. Stubborn Persistent Illusions is the group’s first album in eight years – and a stellar addition to one of the most consistent, inventive, exuberant, satisfying, and critically acclaimed discographies CST120 CONSTELLATION in the ‘post-rock’ canon. Following Other Truths (2009), the five members of DMST pursued other creative TRACKLIST: projects, while all continuing to stay firmly rooted in Toronto. An invite from 01 War On Torpor Heartland Festival and Constellation to play the label’s 15th Anniversary shows in 02 Horripilation Europe in fall 2012 brought DMST back to the stage in very fine form – the band 03 Murder Of Thoughts worked up a bevy of gems from their catalogue and absolutely killed live. A 04 Bound rekindling was sparked, leading to new writing and recording sessions throughout 05 And Boundless 2014-2016. Overdubbing, ‘underdubbing’, gestating and mixing was helmed by 06 Her Eyes On The Horizon band members Ohad Benchetrit, Charles Spearin and Justin Small at Ohad’s 07 d=3.57√h (As Far As The Eye Can See) 08 Shlomo's Son studio th’Schvitz: Stubborn Persistent Illusions is a reminder and continuation of 09 Return, Return Again the group’s DIY ethos, and the integral role played by their singular self- production acumen and aesthetic. -

Nielsen Music Releases 2016 Canada Year-End Report

NIELSEN MUSIC RELEASES 2016 CANADA YEAR-END REPORT Highly Anticipated Report Provides Comprehensive Coverage of the Year in Music NEW YORK, NY Jan. 5, 2017 - Nielsen Music - the industry's leading source for music data and insights - today released its 2016 Canada Year-End Report for the 12-month period ending Dec. 29, 2016. This highly anticipated report provides comprehensive coverage of the year in music from the coveted Nielsen Music Year-End charts, presented by Billboard, to insights on the most important industry trends from sales and streaming to social media and overall consumer engagement across today’s most popular platforms. The Nielsen Music Canada Year-End Report confirms that the music industry experienced steady and consistent growth in 2016, with total audio consumption up 5.3% over 2015, fueled by a 203% increase in on-demand audio streams compared to last year. The industry did experience decreases in digital album and digital track sales, but the growth in streaming led the total digital music consumption to be up over 4% this year. In 2016, catalogue album sales surpassed current sales for the first time in the Nielsen Music-era. 2016 also marked the highest vinyl sales total to date with a 29% increase over 2015. This year’s report shows that six of the top ten best-selling albums for 2016 belong to Canadian artists, with Drake's Views finishing at #1. This marks the first year since 2004 that the top selling album of the year came from a Canadian artist. Five of the top ten airplay songs also belong to Canadian artists, including Justin Bieber's “Love Yourself,” which landed at #1. -

Collectivity, Capitalism, Arts & Crafts and Broken Social Scene

“A BIG, BEAUTIFUL MESS”: COLLECTIVITY, CAPITALISM, ARTS & CRAFTS AND BROKEN SOCIAL SCENE by Ian Dahlman Bachelor of Arts (Hons.), Psychology and Comparative Literature & Culture University of Western Ontario, 2005 London, Ontario, Canada A thesis presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2009 © Ian Dahlman 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59032-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59032-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Gord Downie 1964-2017

Levels 1 & 2 (grades 5 and up) Gord Downie 1964-2017 Article page 2 Questions page 4 Photo page 6 Crossword page 7 Quiz page 8 Breaking news november 2017 A monthly current events resource for Canadian classrooms Routing Slip: (please circulate) National Farewell, Gord Downie – And thank you for the music Th e country was united in sorrow on “If you’re a musician and you’re born “I thought I was going to make it October 17 when singer-songwriter in Canada it’s in your DNA to like through this but I’m not,” the prime Gord Downie died of terminal brain the Tragically Hip,” said Canadian minister said. His voice broke and cancer. He was 53. Mr. Downie was musician Dallas Green. he cried openly. “We all knew it was the front man of Th e Tragically Hip, coming,” Mr. Trudeau said. “But His last great concerts arguably the nation’s most beloved we hoped it wasn’t. We are less as a rock band. Th e band played a series of concerts country without Gordon Downie.” across Canada last summer. Th e CBC “Gord knew this day was coming,” Another fan, Melanie Wells, paid her carried the last show in Kingston. Th e his family wrote on his website. “His respects to Mr. Downie at a day-long broadcast aired in pubs, parks, and response was to spend this precious memorial held in Kingston. “It’s a drive-in movie theatres across the time as he always had – making music, band that’s been with me my whole country. -

Ireland's STUDENT NEWSPAPER of the Year 2005

Ireland’s STUDENT NEWSPAPER Of The Year 2005 Trinity News Est. 1947 Ireland’s Oldest Student Newspaper Tuesday, March 7th, 2006 [email protected] Vol.58 No.7 Win a pair of tickets The TNT Power to this year’s Oxegen! TNT p2-5 GIVEAWAY page 21 List 2006 Arrest in Front Square after foiled GMB raid Gearóid O’ Rourke ed one of the individuals. With the that there had been a vacancy for a from Coolock, has any prior con- arrangement for management of In this incident there was removedfrom the college camous aid of college security this man was security attendant in the GMB for victions. the GMB into the spotlight. A new nothing stolen due to the timely by Gardaí following an incident in Two individuals, described as handed over to the Gardaí. A subse- almost a year yet it had not been If the offence is dealt committee referred to as the GMB intervention of a Hist Committee front square. The college “junkies”, attempted to break into quent search by security revealed filled. It is only in the last two with as a summary offence he management committee in Phil member however some minor dam- Communications Office said the the GMB last Friday and to force that the man had two syringes in weeks that interviews for this posi- could face up to two years in prison documents had been set up at the age was done to the building and issue was a personal one which dd entry to several rooms in the build- his possession.