Talk Into Tune

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Fi Y-Year-Old Environmental Controversy Reaches A

2019 A fiy-year-old environmental controversy reaches a boiling point A DOCUMENTARY FILM BY DAVID W. CRAIG CINEMATOGRAPHER KEVIN FRASER EDITOR PETER GIFFEN LOCATION SOUND JAMES O’TOOLE COMPOSERS JUSTIN SMALL & OHAD BENCHETRIT SOUND DESIGNER JUSTIN GAUDREAULT PRODUCERS ANN BERNIER DAVID W. CRAIG WRITER/DIRECTOR DAVID W. CRAIG A VERTICAL PRODUCTIONS & SITE MEDIA COPRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH CBC, CANADA MEDIA FUND, WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NOVA SCOTIA, NOVA SCOTIA FILM & TELEVISION PRODUCTION INCENTIVE FUND, ONTARIO CREATES FILM & TELEVISION TAX CREDIT, AND THE CANADIAN FILM OR VIDEO FILM TAX CREDIT. EMAIL [email protected] | [email protected] Canada Film or Video PHONE 902-499-4718Production Tax Credit WEB www.themillfilm.ca www.themillfilm.ca SYNOPSES Synopsis (75 words) The Mill is a gripping portrait of a rural community deeply divided over the fate of the local pulp mill. AWARDS Welcome to Pictou County, Nova Scotia where a plan to redirect pulp effluent into the Most Inspirational Feature, Eugene fishing grounds of the Northumberland Strait has stirred controversy. Lobster fishermen Environmental Film Festival say “No Pipe!” The mill says “No Pipe No Mill”. A line has been drawn and with hundreds Nominee: Canadian Screen Award of jobs at stake the issue has reached a boiling point! 2020 Best Documentary Program Nominee: The Kathleen Shannon Short Synopsis (250 words) Award; Director Non-Fiction; Multicultural Award (30 Minutes & The Mill is a gripping portrait of a rural community deeply divided over the fate of the local pulp mill. Over), Yorkton Film Festival In Pictou County, Nova Scotia people have disagreed about the mill since it opened fifty years Environment Award, International ago. -

Ohad Benchetrit - Justin Small

Ohad Benchetrit - Justin Small A bit about us, Ohad Benchetrit & Justin Small: As founding members of critically acclaimed Toronto based band Do Make Say Think, we have been creating engaging, epic, and emotional music together for over 23 years. As composers, our focus has always centered around melody, artistic integrity, passion, and spirited experimentation. This has opened the door to a decades long career in film composition. We’ve always picked projects with lots of heart and beauty and believe score to be an integral part of the story telling. To add color, and emotion but not to lead. To add feel but not to persuade. We’ve been honored with multiple awards, including the 2018 JUNO award for best instrumental album with our work with Do Make Say Think, the Best Original Score in 2016 at the LA scream Fest and a Canadian Screen Award in 2012 for Best original score for a documentary for Semi-Sweet: Life in Chocolate We pride ourselves on finding the right emotional tone that both the director and picture are trying to convey. With Ohad's classical training and Justin's minimalist and immediate sense of melody we feel we have created a unique sound and style of film composition that holds the emotional crux of the entire project in the highest order. We love what we do. AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS JUNO AWARDS (2018) STUBBORN PRESISTENT ILLUSIONS Instrumental Album of the Year *As Do Make Say Think SCREAMFEST (2016) MY FATHER DIE Best Musical Score CANADIAN SCREEN AWARD (2012) SEMI-SWEET: LIFE IN CHOCOLATE Best Original Music for a Non-Fiction Program or Series FEATURE FILM THE DAWNSAYER Paul Kell, prod. -

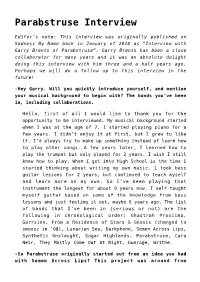

Parabstruse Interview

Parabstruse Interview Editor’s note: This interview was originally published on Sadness By Name back in January of 2010 as “Interview with Garry Brents of Parabstruse”. Garry Brents has been a close collaborator for many years and it was an absolute delight doing this interview with him three and a half years ago. Perhaps we will do a follow up to this interview in the future! -Hey Garry. Will you quickly introduce yourself, and mention your musical background to begin with? The bands you’ve been in, including collaborations. Hello, first of all I would like to thank you for the opportunity to be interviewed. My musical background started when I was at the age of 7. I started playing piano for a few years. I didn’t enjoy it at first, but I grew to like it. I’d always try to make up something instead of learn how to play other songs. A few years later, I learned how to play the trumpet but only played for 2 years. I wish I still knew how to play. When I got into High School is the time I started thinking about writing my own music. I took bass guitar lessons for 2 years, but continued to teach myself and learn more on my own. So I’ve been playing that instrument the longest for about 9 years now. I self-taught myself guitar based on some of the knowledge from bass lessons and just feeling it out, maybe 6 years ago. The list of bands that I’ve been in (serious or not) are the following in chronological order: Ghastrah Proxiima, Garrsinn, From a Residence of Stars & Gnosis (changed to smoosz in ’08), Lunarian Sea, Darkphone, Semen Across Lips, Synthetic Onslaught, Sugar Highlands, Parabstruse, Cara Neir, They Mostly Come Out At Night, bunrage, Writhe. -

Development of Musical Ideas in Compositions by Tortoise

DEVELOPMENT OF MUSICAL IDEAS IN COMPOSITIONS BY TORTOISE Reiner Krämer Prologue For more than 25 years, the Chicago-based experimental rock band Tortoise has crossed over multiple popular music genres (ambient music, krautrock, dub, electronica, drums and bass, reggae, etc.) as well as different types of jazz music, and has made use of minimalist Western art music.1 The group is often labeled a pioneer of the »post-rock« genre. Allegedly, Simon Reynolds first used the term in his review of the album Hex by the English east Lon- don band Bark Psychosis (Reynolds 1994a) and shortly afterwards in his arti- cle »Shaking the Rock Narcotic« (Reynolds 1994b: 28-32). In connection to Tortoise he used »post-rock« in his review article of their 1996 album Mil- lions Now Living Will Never Die (Reynolds 1996). Reynolds describes music he labels as ›post-rock‹ where bands use guitars »in [non-rock] ways« to manipulate »timbre and texture rather than riff[s]« and »augment rock's basic guitar-bass-drums lineup with digital technology such as samplers and sequencers« (Reynolds 2017: 509). Most members of Tortoise act as multi- instrumentalists that play different combinations of instruments at different times. As Jeanette Leech (2017: 16) has stated, a typical Tortoise stage set- up can feature vibraphones, marimbas, two drum sets, and a multitude of synthesizers. With regards to the instrumental setup Leech draws up paral- lels with progressive rock of the 1970s but points to one decisive difference within the genres: »for Tortoise, the range of instrumentation [is] about creating mood, not showboating« (ibid.). -

The Cord Weeklythe Tie That Binds Since 1926 CRISIS, WHAT CRISIS? NETWANKING BACK in BLACK

The Cord WeeklyThe tie that binds since 1926 CRISIS, WHAT CRISIS? NETWANKING BACK IN BLACK . Examining_ the growing food crisis af- Facebook or Twitter? Comparing the Attack in Black talk to The Cord be- ... fecting the world PAGE 10 giants of the social web ... PAGE 12 fore their Thursday show ... PAGE 24 Volume 49 Issue 28 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 1,2009 www.cordweekly.com Culture Jamming The perfect way to spend April Fool's Day. A feature by Kari Pritchard See pages 14-15 Bus pass Curlers extended golden Laurier students to be granted May-August The women's curling coverage with Grand River Transit service team claimed Laurier's 11th national title last MORGAN ALAN in school full-time, they will still weekend in Montreal STAFF WRITER be granted year-round access. A similar system is currently in place Effective May 1, full-time Laurier at the University ofWaterloo. LUKE DOTTO STAFF undergraduate students will be "The benefit to students is quite WRITER able to ride Grand River Transit high, given the number of students (GRT) buses year-round by show- who will be able to access [the ser- History has a tendency to repeat it- ing their Onecards. vice]," said Colin Le Fevre, WLUSU self for the Golden Hawks women's Previously, student fees only president. curling team. One covered GRT bus use for the aca- The expansion will necessitate year after claiming the first ever Canadian Interuniversity demic year. Students wishing to an increase of roughly 18 percent Associa- use public transit in the summer in the bus fee. -

The History of Rock Music - the Nineties

The History of Rock Music - The Nineties The History of Rock Music: 1995-2001 Drum'n'bass, trip-hop, glitch music History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Post-post-rock (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") The Louisville alumni 1995-97 TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The Squirrel Bait and Rodan genealogies continued to dominate Kentucky's and Chicago's post-rock scene during the 1990s. Half of Rodan, i.e. Tara Jane O'Neil (now on vocals and guitar) and Kevin Coultas, formed Sonora Pine with keyboardist and guitarist Sean Meadows, violinist Samara Lubelski and pianist Rachel Grimes. Their debut album, Sonora Pine (1996), basically applied Rodan's aesthetics to the format of the folk lullaby. Another member of Rodan, guitarist Jeff Mueller, formed June Of 44 (11), a sort of supergroup comprising Sonora Pine's guitarist Sean Meadows, Codeine's drummer and keyboardist Doug Scharin, and bassist and trumpet player Fred Erskine. Engine Takes To The Water (1995) signaled the evolution of "slo-core" towards a coldly neurotic form, which achieved a hypnotic and catatonic tone, besides a classic austerity, on the mini-album Tropics And Meridians (1996). Sustained by abrasive and inconclusive guitar doodling, mutant rhythm and off-key counterpoint of violin and trumpet, Four Great Points (1998) metabolized dub, raga, jazz, pop in a theater of calculated gestures. -

Northern Cree When It's Cold Cree Round Dance Songs

Charlotte Cornfield The Shape of Your Name “You free yourself when you take away the script,” says Toronto songwriter Charlotte Artist: Charlotte Cornfield Cornfield. “That’s where this record came from, dismantling patterns and embracing Title: The Shape of Your Name the process.” Cornfield’s third full length, The Shape of Your Name, is set to arrive in Genre: Singer-Songwriter, Indie, Folk April 5, 2019 via Outside Music imprint Next Door Records. The album has a more Recommended if you like Phoebe Bridgers, Big Thief, Julien honed studio sound than her scrappier 2016 release Future Snowbird, and for good Baker, Soccer Mommy, boygenius, Lucy Dacus reason: it was recorded in 5 different sessions over the course of 3 years. The songs are her strongest and most striking to date - contemplative and contemporary, funny Release Date: April 5, 2019 and heart-wrenching - and they’ve got that stuck-in-your-head-for-days quality that LP: NDR0001 Cornfield is known for. The Shape of Your Name features a star-studded cast of LP UPC: 623339912617 collaborators including (but not limited to) Grammy-winning engineer 12” Slip Sleeve Shawn Everett (Kurt Vile, Alabama Shakes, Weezer, Julian Casablancas), Broken Social Scene members Brendan Canning, Kevin Drew and Charles Spearin, and Montreal songwriter Leif Vollebekk. “My initial intention wasn’t to make a record at all,” Cornfield muses. “The whole thing CD: 23339-9126-2 kind of happened by accident. I went to The Banff Centre to do a residency and came CD UPC: 623339912624 out with these recordings that I knew I wanted to use for something but wasn’t sure Digipak what.” She brought the unfinished songs to her former roommate Nigel Ward in Montreal. -

2018 JUNO Award Winners

2018 JUNO Award Winners SINGLE OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY LIVE NATION CANADA) FRANCOPHONE ALBUM OF THE YEAR There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back Shawn Mendes Paloma Daniel Bélanger Audiogram*Sony Island*Universal CHILDREN’S ALBUM OF THE YEAR INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Hear the Music Fred Penner Linus*IDLA DAMN. Kendrick Lamar Interscope*Universal CLASSICAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR: SOLO OR GROUP OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) CHAMBER A Tribe Called Red Pirates Blend*Sony Chopin Recital 3 Janina Fialkowska ATMA*Naxos BREAKTHROUGH GROUP OF THE YEAR CLASSICAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR: LARGE (SPONSORED BY FACTOR, THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, AND CANADA’S PRIVATE RADIO BROADCASTERS) ENSEMBLE The Beaches Universal Chopin: Works for Piano & Orchestra Jan Lisiecki with NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester SONGWRITER OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED BY SOCAN) Deutsche Grammaphon*Universal Gord Downie & Kevin Drew “A Natural”, “Introduce Yerself”, “The North” CLASSICAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR: VOCAL OR INTRODUCE YERSELF – Gord Downie CHORAL Arts & Crafts*Universal Crazy Girl Crazy Barbara Hannigan with Ludwig Orchestra Alpha*Naxos COUNTRY ALBUM OF THE YEAR Game On James Barker Band Universal CLASSICAL COMPOSITION OF THE YEAR My Name is Amanda Todd Jocelyn Morlock ADULT ALTERNATIVE ALBUM OF THE YEAR Analekta*Select Introduce Yerself Gord Downie Arts & Crafts*Universal DANCE RECORDING OF THE YEAR Closer ft. Laurell Nick Fiorucci Hi- ALTERNATIVE ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY Bias*Independent LONG & MCQUADE) Antisocialites Alvvays Royal Mountain*Universal REGGAE RECORDING OF THE -

CST120 CONSTELLATION Do Make Say Think Stubborn Persistent Illusions

Do Make Say Think Stubborn Persistent Illusions 2x180gLP • CD • DL Release Date: 19 May 2017 “Do Make Say Think legitimize post-rock as a term of art... engender some of the most honest, unpretentious, group-oriented rock of their time." – Popmatters “Experimental rock on the grandest and most impressive of scales with not a trace of musical mildew or corrosion." – The Wire “The supernova in Constellation’s stellar network... arguably the finest back catalogue of any currently operating instrumental rock band." – Drowned In Sound Do Make Say Think has been widely celebrated as one of the preeminent instrumental rock bands of the 90s-00s. Stubborn Persistent Illusions is the group’s first album in eight years – and a stellar addition to one of the most consistent, inventive, exuberant, satisfying, and critically acclaimed discographies CST120 CONSTELLATION in the ‘post-rock’ canon. Following Other Truths (2009), the five members of DMST pursued other creative TRACKLIST: projects, while all continuing to stay firmly rooted in Toronto. An invite from 01 War On Torpor Heartland Festival and Constellation to play the label’s 15th Anniversary shows in 02 Horripilation Europe in fall 2012 brought DMST back to the stage in very fine form – the band 03 Murder Of Thoughts worked up a bevy of gems from their catalogue and absolutely killed live. A 04 Bound rekindling was sparked, leading to new writing and recording sessions throughout 05 And Boundless 2014-2016. Overdubbing, ‘underdubbing’, gestating and mixing was helmed by 06 Her Eyes On The Horizon band members Ohad Benchetrit, Charles Spearin and Justin Small at Ohad’s 07 d=3.57√h (As Far As The Eye Can See) 08 Shlomo's Son studio th’Schvitz: Stubborn Persistent Illusions is a reminder and continuation of 09 Return, Return Again the group’s DIY ethos, and the integral role played by their singular self- production acumen and aesthetic. -

2018 JUNO Award Winners

2018 JUNO Award Winners JUNO FAN CHOICE (PRESENTED BY TD) ROCK ALBUM OF THE YEAR Shawn Mendes Island*Universal Young Beauties and Fools The Glorious Sons Black Box*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY LIVE NATION CANADA) There’s Nothing Holdin’ Me Back Shawn Mendes VOCAL JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR Island*Universal Turn Up The Quiet Diana Krall Verve*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR: SOLO DAMN. Kendrick Lamar Interscope*Universal Root Structure Mike Downes Addo ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) JAZZ ALBUM OF THE YEAR: GROUP Everything Now Arcade Fire Sony The North David Braid, Mike Murley, Anders Mogensen & Johnny Aman Addo ARTIST OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Gord Downie Arts & Crafts*Universal INSTRUMENTAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Stubborn Persistent Illusions Do Make Say Think GROUP OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Constellation*Outside A Tribe Called Red Pirates Blend*Sony FRANCOPHONE ALBUM OF THE YEAR BREAKTHROUGH ARTIST OF THE YEAR Paloma Daniel Bélanger Audiogram*Sony (SPONSORED BY FACTOR, THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, AND CANADA’S PRIVATE RADIO BROADCASTERS) CHILDREN’S ALBUM OF THE YEAR Jessie Reyez FMLY*Universal Hear the Music Fred Penner Linus*IDLA BREAKTHROUGH GROUP OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY FACTOR, THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, AND CANADA’S CLASSICAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR: SOLO OR PRIVATE RADIO BROADCASTERS) The Beaches Universal CHAMBER Chopin Recital 3 Janina Fialkowska ATMA*Naxos SONGWRITER OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED -

Collectivity, Capitalism, Arts & Crafts and Broken Social Scene

“A BIG, BEAUTIFUL MESS”: COLLECTIVITY, CAPITALISM, ARTS & CRAFTS AND BROKEN SOCIAL SCENE by Ian Dahlman Bachelor of Arts (Hons.), Psychology and Comparative Literature & Culture University of Western Ontario, 2005 London, Ontario, Canada A thesis presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Program of Communication and Culture Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2009 © Ian Dahlman 2009 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59032-4 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-59032-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

October 19-25, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • What’S Happening at Sweetwater? Artist Events, Workshops, Camps, and More!

OCTOBER 19-25, 2017 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFTWAYNE • WWW.WHATZUP.COM What’s happening at Sweetwater? Artist events, workshops, camps, and more! FREE Pro Tools Master Class OPEN MIC Roll up your sleeves and get hands-on as you learn from Pro Tools expert, and NIGHT professional recording engineer, Nathan Heironimus, right here at Sweetwater. 7–8:30PM every third Monday of the month November 9–11 | 9AM–6PM $995 per person This is a free, family-friendly, all ages event. Bring your acoustic instruments, your voice, and plenty of friends to Sweetwater’s Crescendo Club stage for a great night of local music and entertainment. Buy. Sell. Trade. Play. FREE Have some old gear and looking to upgrade? Bring it in to Sweetwater’s Gear Exchange and get 5–8PM every second and your hands on great gear and incredible prices! fourth Tuesday of the month FREE Hurry in, items move fast! Guitars • Pedals • Amps • Keyboards & More* 7–8:30PM every last Check out Gear Exchange, just inside Sweetwater. Thursday of the month DRUM CIRCLE FREE 7–8PM every first Tuesday of the month *While supplies last Don’t miss any of these events! Check out Sweetwater.com/Events to learn more and to register! Music Store Community Events Music Lessons Sweetwater.com • (260) 432-8176 • 5501 US Hwy 30 W • Fort Wayne, IN 2 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- www.whatzup.com ------------------------------------------------------------October 19, 2017 whatzup Volume 22, Number 12 s local kids from 8 to 80 gear up for the coming weekend’s big Fright Night activi- ties, there’s much to see and do in and around the Fort Wayne area that has noth- ing at all to do with spooks and goblins and ghouls and jack-o-lanterns.