Center 37, the Entire Archive of Center Reports Is Now Accessible and Searchable Online At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Damir Očko Zagreb, 1977

Damir Očko Zagreb, 1977 EDUCATION AND RESIDENCIES 2011 Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Dublin, Ireland 2010 Nordic Art Center Dale, Norway Künstlerresidenz Blumen, Leipzig, Germany 2008-2009 Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart, Germany 2007 HIAP, Helsinki, Finland KulurKontakt, Vienna, Austria Tirana Institute of Contemporary Art, Tirana, Albania 1997-2003 Academy of Fine Arts, Zagreb, Croatia SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2015 Photon - Centre for Contemporary Photography. Ljubljana, Slovenia Studies on Shivering, Gallery Kasia Michalski, Warsaw, Poland 2014 Studies on Shivering, Temple Bar Gallery & Studios, Dublin, Ireland Damir Očko: PST, APOTEKA, Vodnjan, Croatia Studies on Shivering, Künstlerhaus Halle für Kunst & Medien, Graz, Austria (cat.) 2013 Kabinett - ArtBasel Miami (with Yvon Lambert), Miami, US Damir Očko: FILMS, Gallery Tiziana di Caro, Salerno, Italy Psst, TRAPEZ, Budapest, Hungary The Body Score, Yvon Lambert Gallery (project space), Paris, France 2012 Damir Ocko: The Kingdom of Glottis, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France On Ulterior Scale, FIAC (with Gallery Tiziana di Caro), Paris, France On Ulterior Scale, MultiMedia Center Luka, Pula, Croatia Očko/Tadić, Galerie de l’ESAM, Caen, France (With M. Tadić) We saw nothing but the uniform blue of the Sky, Gallery Tiziana di Caro, Salerno, Italy 2011 On Ulterior Scale, Kunsthalle Dusseldorf, Dusseldorf, Germany (cat.) Jedinstvo Hall - Gallery Močvara, 26th Music Biennale, Zagreb, Croatia 2010 Castle & Elephant, Coventry, UK Event Horizon, Kunstverein Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany The Age of Happiness, Tiziana di Caro Gallery, Salerno, Italy Screening Room, Blumen, Leipzig, Germany 2009 The Age of Happiness, Lothringer13 Städtische Kunsthalle München, Munich, Germany (cat.) The Age of Happiness, Akademie Schloss Solitude, Stuttgart, Germany 2007 The End of the World, Miroslav Kraljević Gallery, Zagreb, Croatia Why does Gravity make things fall?, Tirana Institute of Contemporary Art, Tirana, Albania (With N. -

Experiments in the Performance of Participation and Democracy

Respublika! Experiments in the performance of participation and democracy edited by Nico Carpentier 1 2 3 Publisher NeMe, Cyprus, 2019 www.neme.org © 2019 NeMe Design by Natalie Demetriou, ndLine. Printed in Cyprus by Lithografica ISBN 978-9963-9695-8-6 Copyright for all texts and images remains with original artists and authors Respublika! A Cypriot community media arts festival was realised with the kind support from: main funder other funders in collaboration with support Further support has been provided by: CUTradio, Hoi Polloi (Simon Bahceli), Home for Cooperation, IKME Sociopolitical Studies Institute, Join2Media, KEY-Innovation in Culture, Education and Youth, Materia (Sotia Nicolaou and Marina Polycarpou), MYCYradio, Old Nicosia Revealed, Studio 21 (Dervish Zeybek), Uppsala Stadsteater, Chystalleni Loizidou, Evi Tselika, Anastasia Demosthenous, Angeliki Gazi, Hack66, Limassol Hacker Space, and Lefkosia Hacker Space. Respublika! Experiments in the performance of participation and democracy edited by Nico Carpentier viii Contents Foreword xv An Introduction to Respublika! Experiments in the Performance of 3 Participation and Democracy Nico Carpentier Part I: Participations 14 Introduction to Participations 17 Nico Carpentier Community Media as Rhizome 19 Nico Carpentier The Art of Community Media Organisations 29 Nico Carpentier Shaking the Airwaves: Participatory Radio Practices 34 Helen Hahmann Life:Moving 42 Briony Campbell and the Life:Moving participants and project team Life:Moving - The Six Participants 47 Briony Campbell -

Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities ~ .~ I1{, ~ -1~, dr \ --"-x r-i>- : ........ :i ' i 1 ~,1": "~ .-~ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1984---May 1985 Washington, 1985 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without thc written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1985 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: Gavarni, "Les Artistes," no. 2 (printed by Aubert et Cie.), published in Le Charivari, 24 May 1838. "Vois-tu camarade. Voil~ comme tu trouveras toujours les vrais Artistes... se partageant tout." CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 13 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1984-1985 (June 1984-May 1985) Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Advisory Group 16 Members 16 Meetings 21 Members' Research Reports Reports 32 i !~t IJ ii~ . ~ ~ ~ i.~,~ ~ - ~'~,i'~,~ ii~ ~,i~i!~-i~ ~'~'S~.~~. ,~," ~'~ i , \ HE CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars. -

Saints, Signs Symbols

\ SAINTS, SIGNS and SYMBOLS by W. ELLWOOD POST Illustrated and revised by the author FOREWORD BY EDWARD N. WEST SECOND EDITION CHRIST THE KING A symbol composed of the Chi Rho and crown. The crown and Chi are gold with Rho of silver on a blue field. First published in Great Britain in 1964 Fourteenth impression 1999 SPCK Holy Trinity Church Acknowledgements Marylebone Road London NW1 4DU To the Rev. Dr. Edward N. West, Canon Sacrist of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, New York, who has © 1962, 1974 by Morehouse-Barlow Co. graciously given of his scholarly knowledge and fatherly encouragement, I express my sincere gratitude. Also, 1 wish to ISBN 0 281 02894 X tender my thanks to the Rev. Frank V. H. Carthy, Rector of Christ Church, New Brunswick, New Jersey, who initiated my Printed in Great Britain by interest in the drama of the Church; and to my wife, Bette, for Hart-Talbot Printers Ltd her loyal co-operation. Saffron Walden, Essex The research material used has been invaluable, and I am indebted to writers, past and contemporary. They are: E. E. Dorling, Heraldry of the Church; Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, Guide to Heraldry; Shirley C. Hughson of the Order of the Holy Cross, Athletes of God; Dr. F. C. Husenbeth Emblems of Saints; C. Wilfrid Scott-Giles, The Romance of Heraldry; and F. R. Webber, Church Symbolism. W. ELLWOOD POST Foreword Contents Ellwood Post's book is a genuine addition to the ecclesiological library. It contains a monumental mass of material which is not Page ordinarily available in one book - particularly if the reader must depend in general on the English language. -

April 17, 2020 Vol

‘A big void’ Priests, laity saddened by absence of chrism Mass, page 11. Serving the Church in Central and Southern Indiana Since 1960 CriterionOnline.com April 17, 2020 Vol. LX, No. 27 75¢ Pope calls for As students at Father Thomas Scecina Memorial a ‘contagion’ High School in Indianapolis, of Easter hope, twins Eliza and A prayer amid Luke Leffler peace, care have found their the pain prayers and their conversations for the poor with God VATICAN CITY (CNS)—In an Easter increasing as celebration like no other, Pope Francis they and all other prayed that Christ, “who has already high school defeated death and seniors across opened for us the way the archdiocese to eternal salvation,” deal with the would “dispel the coronavirus darkness of our ending their suffering humanity and hopes for prom, lead us into the light of one last sports his glorious day, a day season and that knows no end.” other activities The pope’s traditional and traditions of Pope Francis Easter message before their senior year. his blessing “urbi (Submitted photo) et orbi” (“to the city and the world”) still mentioned countries yearning for peace, migrants and refugees in need of a welcoming home and the poor deserving of assistance. But his Easter prayers on April 12 were mostly in the context of the suffering and death caused by the coronavirus and the economic difficulties the pandemic already has triggered. The pope’s Easter morning Mass was unique; missing were dozens of cardinals High school seniors turn to God as concelebrating and tens of thousands of pilgrims from around the world packing St. -

Travel Guide

TRAVEL GUIDE Traces of the COLD WAR PERIOD The Countries around THE BALTIC SEA Johannes Bach Rasmussen 1 Traces of the Cold War Period: Military Installations and Towns, Prisons, Partisan Bunkers Travel Guide. Traces of the Cold War Period The Countries around the Baltic Sea TemaNord 2010:574 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2121-1 Print: Arco Grafisk A/S, Skive Layout: Eva Ahnoff, Morten Kjærgaard Maps and drawings: Arne Erik Larsen Copies: 1500 Printed on environmentally friendly paper. This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/ publications Printed in Denmark T R 8 Y 1 K 6 S 1- AG NR. 54 The book is produced in cooperation between Øhavsmuseet and The Baltic Initiative and Network. Øhavsmuseet (The Archipelago Museum) Department Langelands Museum Jens Winthers Vej 12, 5900 Rudkøbing, Denmark. Phone: +45 63 51 63 00 E-mail: [email protected] The Baltic Initiative and Network Att. Johannes Bach Rasmussen Møllegade 20, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark. Phone: +45 35 36 05 59. Mobile: +45 30 25 05 59 E-mail: [email protected] Top: The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga, Latvia. From the Days of the Barricades in 1991 when people in the newly independent country tried to defend key institutions from attack from Soviet military and security forces. Middle: The Anna Akhmatova Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Handwritten bark book with Akhmatova’s lyrics. Made by a GULAG prisoner, wife of an executed “enemy of the people”. Bottom: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania. -

Ing Items Have Been Registered

ACCEPTANCES Page 1 of 38 December 2018 LoAR THE FOLLOWING ITEMS HAVE BEEN REGISTERED: ÆTHELMEARC Æthelmearc, Kingdom of. Badge. Azure, in cross an axe and a knife argent, a bordure Or. Æthelmearc, Kingdom of. Badge. Gules, in cross an axe and a knife argent, a bordure Or. Æthelmearc, Kingdom of. Badge. Purpure, in cross an axe and a knife argent, a bordure Or. Æthelmearc, Kingdom of. Badge. Sable, in cross an axe and a knife argent, a bordure Or. Æthelmearc, Kingdom of. Badge. Vert, in cross an axe and a knife argent, a bordure Or. Anna Leigh. Badge. (Fieldless) On a rose gules a wolf’s head cabossed argent. Masina d’Alessandro. Device. Per bend gules and sable, in sinister chief a cross bottony argent. This device does not conflict with the badge of David of Moffat, (Fieldless) A cross-crosslet argent quarter-pierced gules. There is one DC for fieldlessness. The quarter-piercing of David’s badge is the equivalent of a tertiary delf, which provides the necessary second DC. AN TIR Adele Marie Purrier. Name. The Letter of Intent documented the given name Adele in 16th Switzerland. However, Adele is the likely vernacular form of the Latinized English given name Adela, which was documented in commentary. Therefore, the name is entirely English. Aonghus Keith. Device. Per bend sinister gules and sable, a winged sea-unicorn and a chief rayonny argent. Bella Valencia. Name. Bran Dubh Ua Mic Raith. Name. Submitted as Bran Dubh Ua Mac Raith, the byname was not correctly formed. Gaelic grammar requires the ancestor’s name to be in the genitive form following Ua. -

FRIDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2012 Berengaria Room, Evagoras Lanitis Centre, Limassol

FRIDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2012 Berengaria Room, Evagoras Lanitis Centre, Limassol 1 FRIDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2012 Berengaria Room, Evagoras Lanitis Centre, Limassol DAY 1 11:00 - 13:30 Morning Session In Context: art in translation Introduction: Helene Black/Antonis Danos IntModeroduction:rator: Denise Helene Robinson Black / Dr Antonis Danos Narcissus, Iannis Zannos GR, Jean-Pierre Hébert FR/US The Utopia Disaster, Marianna Christofides CY/DE, Bernd Bräunlich DE The Negotiation Table, George Alexander AU, Phil George AU Considerations on Reactions and A Small Picture: Fine Art and Research Methodologies in Collaborative Artistic and Curatorial Projects, Lanfranco Aceti UK/TR, Çağlar Çetin TR The Persistence of the Image, Gabriel Koureas CY/UK, Klitsa Antoniou CY 15:00 - 17:30 Afternoon Session In Context: art in translation Moderator: Denise Robinson Strawberry fields…: Global economic crisis, simulacra, maps, and simulated borderlines, Antonis Danos CY, Nicos Synnos CY, Yiannis Christidis GR/CY, Yannos Economou CY, Yannis Yapanis CY The Shock of Modernity, Guli Silberstein IL/UK, Tal Kaminer IL/UK Destination Is Never A Place, Peter Lyssiotis CY/AU, Helene Black CY Hybrid spatial experiences overcoming physical boundaries, Dimitris Charitos GR, Coti K IT/GR ‘Roaming Trans_cities and Airborne Fiction -- click the image to enlarge and zoom in’, Shameen Syed PK/UAE, George Katodrytis CY/UAE 20:00 - 22:00 DISTINGUISHED KEYNOTE SPEAKER Pefkios Georgiades Amphitheatre, Cyprus University of Technology, Limassol Introduction: Srećko Horvat No Definitions -

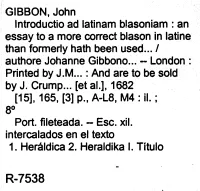

R-7538 G.Qs a ? / T'

GIBBON, John Introducilo ad latìnam blasoniam : an essay to a more correct blason in latine than formerly hath been used... / authore Johanne Gibbono... - London : Printed by J.M... : And are tobe sold by J. Crump... [et al.], 1682 [15], 165, [3] p., A-L8, M4 : il. ; g o Port, fileteada. — Esc. xil. intercalados en el texto 1. Heráldica 2. Heraldika I. Titulo R-7538 g.qs a ? / t' * £ iteratura, Heráldica pracipuè , necnon Hi* jiorica, admodum ftudiofis , fequens Tra= LBatus, cui Titulm, Introduco ad Latinam plafoniam, obnixé recommendatur per Gulielmum Dugdale, Eq. Aur. (Prinápalem Armorum $(egem, cognomento Garter. Hen. S. George, Eq. Aur. Clarenceux ${egem Armorum. J Tho. S. George, Eq. Aur. “Morroy I(egem Armorum. Eliam Afhmole Arnig. * { * * Quem, TraBatm Ordinis Georgiani An glicani (<vulgo Garteriani diBi) apud Europeos aterno nomine beaYtt, <£?* qui non ita pridem fuit fécialis Windjorienjìs. “ -T t- ■ * I N TR O D U CTIO AD Latinam Blafoniam. AN' Eflay to a more Correft BLASON In Latine than formerly hath been ufed.' COLLECTED Out o f Approved Modern Authors, and de- icribing the Arms of all the Kingdoms o f Europe, and of many ofthe greateft Princes! ■ and Potentates thereof: Together with many other Illuftrious and Ancient Houfes both of England and other Countries. No Work of this Nature extant in our Engliih Tongue, nor (abfit glorUri) of its Method and ; Circumftances in any Foreign Language what- foever. — -------------- -— — ----------------------------------------------------- 1— Authore J O H ANNE, (j IB BO NO Armorttm Servulo, quern a Mrnelio dicunt C&rnUo. LONDON, Printed by J. M, for the Author, and are to be fold by J. -

This Plea Is Not a Ploy to Get More Money to an Underfinanced Sector

--------------------- Gentiana Rosetti Maura Menegatti Franca Camurato Straumann Mai-Britt Schultz Annemie Geerts Doru Jijian Drevariuc Pepa Peneva Barbara Minden Sandro Novosel Mircea Martin Doris Funi Pedro Biscaia Jean-Franois Noville Adina Popescu Natalia Boiadjieva Pyne Frederick Laura Cockett Francisca Van Der Glas Jesper Harvest Marina Torres Naveira Giorgio Baracco Basma El Husseiny Lynn Caroline Brker Louise Blackwell Leslika Iacovidou Ludmila Szewczuk Xenophon Kelsey Renata Zeciene Menndez Agata Cis Silke Kirchhof Antonia Milcheva Elsa Proudhon Barruetabea Dagmar Gester Sophie Bugnon Mathias Lindner Andrew Mac Namara SIGNED BY Zoran Petrovski Cludio Silva Carfagno Jordi Roch Livia Amabilino Claudia Meschiari Elena Silvestri Gioele Pagliaccia Colimard Louise Mihai Iancu Tamara Orozco Ritchie Robertson Caroline Strubbe Stphane Olivier Eliane Bots Florent Perrin Frederick Lamothe Alexandre Andrea Wiarda Robert Julian Kindred Jaume Nadal Nina Jukic Gisela Weimann Mihon Niculescu Laura Alexandra Timofte Nicos Iacovides Maialen Gredilla Boujraf Farida Denise Hennessy-Mills Adolfo Domingo Ouedraogo Antoine D Ivan Gluevi Dilyana Daneva Milena Stagni Fran Mazon Ermis Theodorakis Daniela Demalde’ Adrien Godard Stuart Gill --------------------- Kliment Poposki Maja Kraigher Roger Christmann Andrea-Nartano Anton Merks Katleen Schueremans Daniela Esposito Antoni Donchev Lucy Healy-Kelly Gligor Horia Fernando De Torres Olinka Vitica Vistica Pedro Arroyo Nicolas Ancion Sarunas Surblys Diana Battisti Flesch Eloi Miklos Ambrozy Ian Beavis Mbe -

Retooling Medievalism for Early Modern Painting in Annibale Carracci’S Pietà with Saints in Parma

religions Article Retooling Medievalism for Early Modern Painting in Annibale Carracci’s Pietà with Saints in Parma Livia Stoenescu Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Annibale Carracci (1560–1609) drew on the Italian Renaissance tradition of the Man of Sorrows to advance the Christological message within the altarpiece context of his Pietà with Saints (1585). From its location at the high altar of the Capuchin church of St. Mary Magdalene in Parma, the work commemorates the life of Duke Alessandro Farnese (1586–1592), who is interred right in front of Annibale’s painted image. The narrative development of the Pietà with Saints transformed the late medieval Lamentation altarpiece focused on the dead Christ into a riveting manifestation of the beautiful and sleeping Christ worshipped by saints and angels in a nocturnal landscape. Thus eschewing historical context, the pictorial thrust of Annibale’s interpretation of the Man of Sorrows attached to the Pietà with Saints was to heighten Eucharistic meaning while allowing for sixteenth- century theological and poetic thought of Mary’s body as the tomb of Christ to cast discriminating devotional overtones on the resting place of the deceased Farnese Duke. Keywords: Devotional Art; Reform of Art; Early Modern and Italian Renaissance Art The Pietà with Saints (Figure1) for the high altar of the Capuchin church of Saint Mary Magdalene in Parma articulates the increasing attention brought to the aesthetic qualities Citation: Stoenescu, Livia. 2021. of the Man of Sorrows tradition and the value placed on creative imitation on the part Retooling Medievalism for Early of its maker, Annibale Carracci (1560–1609). -

A Journal of International Children's Literature

A JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL CHILDREN’S LITERATURE 2018, VOL . 56, NO .4 The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Copyright © 2018 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Editor: Björn Sundmark, Malmö University, Sweden. Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected]. Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Faculty of Education, Malmö University, Sweden Editorial Review Board: Peter E. Cumming, York University (Canada); Debra Dudek, University of Wollongong (Australia); Helene Høyrup, Royal School of Library & Information Science (Denmark); Judith Inggs, University of the Witwatersrand (South Africa); Ingrid Johnston, University of Alberta (Canada); Michelle Martin, University of South Carolina (USA); Beatriz Alcubierre Moya, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (Mexico); Lissa Paul, Brock University (Canada); Margaret Zeegers, University of Ballarat (Australia); Lydia Kokkola, Luleå University (Sweden); Roxanne Harde, University of Alberta (Canada), Gargi Gangophadhyay, Ramakrishna Sarada Mission Vivekananda Vidyabhavan (India); Tami al-Hazza, Old Dominion University (USA); Farideh Pourgiv, Shiraz University Center for Children’s Literature Studies (Iran); Anna Kérchy, University of Szeged (Hungary); Andrea Mei Ying Wu, National Cheng kung University (Taiwan); Junko Sakoi, Tucson, AZ, (USA). Board of Bookbird, Inc. (An Indiana not-for-profit corporation): Valerie Coghlan President; Ellis Vance Treasurer; Junko Yokota Secretary; Hasmig Chahinian; Sylvia Vardell. Advertising Manager: Ellis Vance ([email protected]) Production: Design and layout by Mats Hedman. Printed by The Sheridan Press, Hanover, Pennsylvania, USA Bookbird: A Journal of International Children’s Literature (ISSN 0006-7377) issue October 2018 is a refereed journal published quarterly in January, April, July and October by IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People, and distributed by Johns Hopkins University Press, 2715 N.