Center 29 National Gallery of Art Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Center 29

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rijksmuseum Bulletin

the rijksmuseum bulletin 114 the rijks the amsterdam paradise of herri metmuseum de bles and the fountain of life bulletin The Amsterdam Paradise by Herri * met de Bles and the Fountain of Life • boudewijn bakker • ne of the most intriguing early Fig. 1 the birds, the creatures of the land and O landscape paintings in the herri met de bles, human beings.2 The Creator made man Rijksmuseum is Paradise by Herri met Paradise, c. 1541-50. a place to dwell, ‘a garden eastward in de Bles (fig. 1). The more closely the Oil on panel, Eden’, with the tree of life and the tree 46.6 x 45.5 cm. modern-day viewer examines this of the knowledge of good and evil, and Amsterdam, small panel with its extremely detailed Rijksmuseum, a river that watered the garden, then scene, the more questions it raises. inv. no. sk-a-780. parted to become four branches. The Several authors have consequently artist shows us the two primal trees in endeavoured to coax the work into paradise, and the source of the primal giving up its secrets. river in the form of an elegant fountain The panel is round and has a sawn with four spouts.3 bevelled edge. It was almost certainly In this idyllic setting, which occupies originally contained in a carved round roughly the lower half of the landscape, wooden frame that was later removed.1 Bles pictures the tragic story of the Fall The composition is divided into con- in four scenes, following the sequence centric bands around a circular central of the days of the Creation: the creation section in which we see paradise; beside of Eve from Adam’s rib, God forbidding and behind it is a panoramic ‘world them to eat fruit from the tree of the landscape’. -

NEWSLETTER 43 Antikvariat Morris · Badhusgatan 16 · 151 73 Södertälje · Sweden [email protected] |

NEWSLETTER 43 antikvariat morris · badhusgatan 16 · 151 73 södertälje · sweden [email protected] | http://www.antikvariatmorris.se/ [dwiggins & goudy] browning, robert: In a Balcony The Blue Sky Press, Chicago. 1902. 72 pages. 8vo. Cloth spine with paper label, title lettered gilt on front board, top edge trimmed others uncut. spine and boards worn. Some upper case letters on title page plus first initial hand coloured. Introduction by Laura Mc Adoo Triggs. Book designs by F. W. Goudy & W. A. Dwiggins. Printed in red & black by by A.G. Langworthy on Van Gelder paper in a limited edition. This is Nr. 166 of 400 copies. Initialazed by Langworthy. One of Dwiggins first book designs together with his teacher Goudy. “Will contributed endpapers and other decorations to In a Balcony , but the title page spread is pure Goudy.” Bruce Kennett p. 20 & 28–29. (Not in Agner, Ransom 19). SEK500 / €49 / £43 / $57 [dwiggins] wells, h. g.: The Time Machine. An invention Random House, New York. 1931. x, 86 pages. 8vo. Illustrated paper boards, black cloth spine stamped in gold. Corners with light wear, book plate inside front cover (Tage la Cour). Text printed in red and black. Set in Monotype Fournier and printed on Hamilton An - dorra paper. Stencil style colour illustrations. Typography, illustra - tions and binding by William Addison Dwiggins. (Agner 31.07, Bruce Kennett pp. 229–31). SEK500 / €49 / £43 / $57 [bodoni] guarini, giovan battista: Pastor Fido Impresso co’ Tipi Bodoniani, Crisopoli [Parma], 1793. (4, first 2 blank), (1)–345, (3 blank) pages. Tall 4to (31 x 22 cm). -

SOPHIE SCHNEIDEMAN RARE BOOKS Catalogue 21

SOPHIE SCHNEIDEMAN RARE BOOKS Catalogue 21 Sophie Schneideman RARE BOOKS CATALOGUE ILLUSTRATED & PRIVATE PRESS BOOKS, ARTISTS’ BOOKS, BOOKBINDINGS, ART We prefer to give customers on our mailing list the opportunity to buy books from catalogues before we put items up for sale on our website. Items in this catalogue will be posted onto www.ssrbooks.com a week or so after the catalogue has been sent out and in many cases there will be additional photographs to view there. If you are interested in buying or selling rare books, need a valuation or just honest advice please contact me at: SCHNEIDEMAN GALLERY Open by appointment days a week or by chance – usually Mon-Fri –. The gallery is open on Saturday – but if you want to view the books please let me know in advance. Portobello Road, London, w sa [email protected] www.ssrbooks.com WE ARE PROUD TO BE A MEMBER OF THE ABA, PBFA & ILAB AND ARE PLEASED TO FOLLOW THEIR CODES OF CONDUCT Prices are in sterling and payment to Sophie Schneideman Rare Books by bank transfer, cheque or credit card is due upon receipt. All books are sent on approval and can be returned within days by secure means if they have been wrongly or inadequately described. Postage is charged at cost. EU members,, please quote your vat/tva number when ordering. The goods shall legally remain the property of Sophie Schneideman Rare Books until the price has been discharged in full. Printed in Great Britain by Henry Ling Ltd, Dorchester Designed in Adobe Jenson by Geoff Green Book Design, Cambridge Adobe Jenson is based on the designs of Nicholas Jenson’s typeface, first cut in . -

Michaelangelo's Sistine Chapel: the Exhibition

2018- 2019 © TACOMA'S HISTORIC THEATER DISTRICT PANTAGES THEATER • RIALTO THEATER THEATER ON THE SQUARE •TACOMA ARMORY My legacy. My partner. You have dreams. Goals you want to achieve during your lifetime and a legacy you want to leave behind. The Private Bank can help. Our highly specialized and experienced wealth strategists can help you navigate the complexities of estate planning and deliver the customized solutions you need to ensure your wealth is transferred according to your wishes. To learn more, please visit unionbank.com/theprivatebank or contact: Lisa Roberts Managing Director, Private Wealth Management [email protected] 415-705-7159 Wills, trusts, foundations, and wealth planning strategies have legal, tax, accounting, and other implications. Clients should consult a legal or tax advisor. ©2018 MUFG Union Bank, N.A. All rights reserved.Member FDIC. Equal Housing Lender. Union Bank is a registered trademark and brand name of MUFG Union Bank, N.A. unionbank.com Welcome to the 2018–19 Season The Broadway Center’s mission is to energize community through live performance. The performing arts, as the pulse of the city, radiate a vital and joyful energy and engage in the momentum of social change. With 35+ events to choose from in the 2018-19 season, we hope you’ll connect and discover remarkable and transformative experiences in the year ahead. For all upcoming events, visit www.BroadwayCenter.org. My legacy. My partner. You have dreams. Goals you want to achieve during your lifetime and a legacy you want to leave behind. The Private Bank can help. Our highly specialized and experienced wealth strategists can help you navigate the complexities of estate planning and deliver the customized solutions you need to ensure your wealth is transferred according to your wishes. -

Full Program & Logistics Hna 2018

Thank you for wearing your badge at all locations. You will need to be able to identify at any moment during the conference. WIFI at Het Pand (GHENT) Network: UGentGuest Login: guestHna1 Password: 57deRGj4 3 WELCOME Welcome to Ghent and Bruges for the 2018 Historians of Netherlandish Art Conference! This is the ninth international quadrennial conference of HNA and the first on the campus of Ghent University. HNA will move to a triennial format with our next conference in 2021. HNA is extremely grateful to Ghent University, Groeningemuseum Bruges, St. John’s Hospital Bruges, and Het Grootseminarie Bruges for placing lecture halls at our disposal and for hosting workshops. HNA would like to express its gratitude in particular to Prof. dr. Maximiliaan Martens and Prof. dr. Koenraad Jonckheere for the initiative and the negotiation of these arrangements. HNA and Ghent University are thankful to the many sponsors who have contributed so generously to this event. A generous grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation provided travel assistance for some of our North American speakers and chairs. The opening reception is offered by the city of Ghent, for which we thank Annelies Storms, City Councillor of Culture, in particular. We are grateful to our colleagues of the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent for the reception on Thursday and for offering free admission to conference participants. Also the Museum Het Zotte Kunstkabinet in Mechelen offers free entrance during the conference, for which we are grateful. In addition we also like to thank the sponsoring publishers, who will exhibit books on Thursday. This conference would not have been possible without the efforts of numerous individuals. -

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected]. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

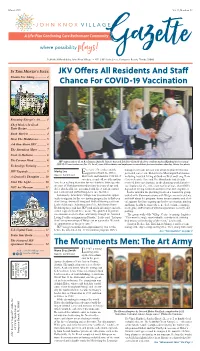

JKV Offers All Residents and Staff Chance for COVID-19 Vaccination

March 2021 Vol. 8, Number 12 A Life-Plan Continuing Care Retirement Community Published Monthly by John Knox Village • 651 S.W. Sixth Street, Pompano Beach, Florida 33060 In This Month’s Issue JKV Offers All Residents And Staff Thanks For Asking ............... 2 Chance For COVID-19 Vaccination Rescuing Europe’s Art ....... 3 Chef Mark’s In Good Taste Recipe ........................ 4 Book Review ..................... 4 Meet The Middletons .......... 5 Ask Kim About JKV ............ 6 The Stressless Move .......... 7 Food As Medicine ................. 8 The Curious Mind ................. 8 JKV staff members (L. to R.) Susanne Russell, Joanne Avis and Loli Pire-Schmidt check-in resident Andrea Hipskind for her initial COVID-19 vaccination on Jan. 19. In all, some 800 residents and employees received their first vaccinations that day. Marty Lee photo. Technology Training ............ 9 ver since December and the management team jumped into action to plan for this ma- JKV Expands ........................ 9 Marty Lee approval of both the Pfizer- jor health care event. Elders in the Meaningful Life homes Gazette Contributor E A General’s Thoughts ...... 10 BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 including Assisted Living at Gardens West and Long-Term vaccines, people all over the nation Care in Seaside Cove and The Woodlands had already Find The Light ................. 10 have been seeking their turn for vaccinations. Subsequently, received their vaccinations, so the planning would involve the state of Florida prioritized persons 65 years of age and vaccinations for the entire community of more than 600 In- NSU Art Museum ............... 11 older, plus health care personnel with direct patient contact dependent Living residents and more than 600 employees. -

A History of Italian Literature Should Follow and Should Precede Other and Parallel Histories

I. i III 2.3 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY C U rar,y Ubrary PQ4038 G°2l"l 8t8a iterature 1lwBiiMiiiiiiiifiiliiii ! 3 1924 oim 030 978 245 Date Due M#£ (£i* The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030978245 Short Histories of the Literatures of the World: IV. Edited by Edmund Gosse Short Histories of the Literatures of the World Edited by EDMUND GOSSE Large Crown 8vOj cloth, 6s. each Volume ANCIENT GREEK LITERATURE By Prof. Gilbert Murray, M.A. FRENCH LITERATURE By Prof. Edward Dowden, D.C.L., LL.D. MODERN ENGLISH LITERATURE By the Editor ITALIAN LITERATURE By Richard Garnett, C.B., LL.D. SPANISH LITERATURE By J. Fitzmaurice-Kelly [Shortly JAPANESE LITERATURE By William George Aston, C.M.G. [Shortly MODERN SCANDINAVIAN LITERATURE By George Brandes SANSKRIT LITERATURE By Prof. A. A. Macdonell. HUNGARIAN LITERATURE By Dr. Zoltan Beothy AMERICAN LITERATURE By Professor Moses Coit Tyler GERMAN LITERATURE By Dr. C. H. Herford LATIN LITERATURE By Dr. A. W. Verrall Other volumes will follow LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN \AU rights reserved] A .History of ITALIAN LITERATURE RICHARD GARNETT, C.B., LL.D. Xon&on WILLIAM HEINEMANN MDCCCXCVIII v y. 1 1- fc V- < V ml' 1 , x.?*a»/? Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &* Co. At the Ballantyne Press *. # / ' ri PREFACE "I think," says Jowett, writing to John Addington Symonds (August 4, 1890), "that you are happy in having unlocked so much of Italian literature, certainly the greatest in the world after Greek, Latin, English. -

Collecting Haudenosaunee Art from the Modern Era

arts Article Collecting Haudenosaunee Art from the Modern Era Scott Manning Stevens Native American and Indigenous Studies Program, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY 13244, USA; [email protected] Received: 18 October 2019; Accepted: 15 March 2020; Published: 29 April 2020 Abstract: My essay considers the history of collecting the art of Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) artists in the twentieth century. For decades Native visual and material culture was viewed under the guise of ‘crafts.’ I look back to the work of Lewis Henry Morgan on Haudenosaunee material culture. His writings helped establish a specific notion of Haudenosaunee material culture within the scholarly field of anthropology in the nineteenth century. At that point two-dimensional arts did not play a substantial role in Haudenosaunee visual culture, even though both Tuscarora and Seneca artists had produced drawings and paintings then. I investigate the turn toward collecting two-dimensional Haudenosaunee representational art, where before there was only craft. I locate this turn at the beginning of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration in the 1930s. It was at this point that Seneca anthropologist Arthur C. Parker recruited Native crafts people and painters working in two-dimensional art forms to participate in a Works Progress Administration-sponsored project known as the Seneca Arts Program. Thereafter, museum collectors began purchasing and displaying paintings by the artists: Jesse Cornplanter, Sanford Plummer, and Ernest Smith. I argue that their representation in museum collections opened the door for the contemporary Haudenosaunee to follow. Keywords: Haudenosaunee; Seneca arts program; crafts; authenticity; cultural specificity What are the parameters of Native American art in relationship to modern or contemporary art? Do tribal and regional idioms fall away? Do formalist concerns prevail? Can art be individualistic rather than communitarian in its subjects? All these are questions are asked by scholars and viewers alike. -

BM Tour to View

08/06/2020 Gods and Heroes The influence of the Classical World on Art in the C17th and C18th The Tour of the British Museum Room 2a the Waddesdon Bequest from Baron Ferdinand Rothschild 1898 Hercules and Achelous c 1650-1675 Austrian 1 2 Limoges enamel tazza with Judith and Holofernes in the bowl, Joseph and Potiphar’s wife on the foot and the Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite/Venus on the stem (see next slide) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600-1630 Omphale by Artus Quellinus the Elder 1640-1668 Flanders 3 4 see previous slide Limoges enamel salt-cellar of piédouche type with Diana in the bowl and a Muse (with triangle), Mercury, Diana (with moon), Mars, Juno (with peacock) and Venus (with flaming heart) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600- 1630 (also see next slide) 5 6 1 08/06/2020 Nautilus shell cup mounted with silver with Neptune on horseback on top 1600-1650 probably made in the Netherlands 7 8 Neptune supporting a Nautilus cup dated 1741 Dresden Opal glass beaker representing the Triumph of Neptune c 1680 Bohemia 9 10 Room 2 Marble figure of a girl possibly a nymph of Artemis restored by Angellini as knucklebone player from the Garden of Sallust Rome C1st-2nd AD discovered 1764 and acquired by Charles Townley on his first Grand Tour in 1768. Townley’s collection came to the museum on his death in 1805 11 12 2 08/06/2020 Charles Townley with his collection which he opened to discerning friends and the public, in a painting by Johann Zoffany of 1782. -

The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti by John Addington Symonds</H1>

The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti by John Addington Symonds The Life of Michelangelo Buonarroti by John Addington Symonds Produced by Ted Garvin, Keith M. Eckrich and PG Distributed Proofreaders THE LIFE OF MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI By JOHN ADDINGTON SYMONDS TO THE CAVALIERE GUIDO BIAGI, DOCTOR IN LETTERS, PREFECT OF THE MEDICEO-LAURENTIAN LIBRARY, ETC., ETC. I DEDICATE THIS WORK ON MICHELANGELO IN RESPECT FOR HIS SCHOLARSHIP AND LEARNING ADMIRATION OF HIS TUSCAN STYLE AND GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGMENT OF HIS GENEROUS ASSISTANCE CONTENTS CHAPTER page 1 / 658 I. BIRTH, BOYHOOD, YOUTH AT FLORENCE, DOWN TO LORENZO DE' MEDICI'S DEATH. 1475-1492. II. FIRST VISITS TO BOLOGNA AND ROME--THE MADONNA DELLA FEBBRE AND OTHER WORKS IN MARBLE. 1492-1501. III. RESIDENCE IN FLORENCE--THE DAVID. 1501-1505. IV. JULIUS II. CALLS MICHELANGELO TO ROME--PROJECT FOR THE POPE'S TOMB--THE REBUILDING OF S. PETER'S--FLIGHT FROM ROME--CARTOON FOR THE BATTLE OF PISA. 1505, 1506. V. SECOND VISIT TO BOLOGNA--THE BRONZE STATUE OF JULIUS II--PAINTING OF THE SISTINE VAULT. 1506-1512. VI. ON MICHELANGELO AS DRAUGHTSMAN, PAINTER, SCULPTOR. VII. LEO X. PLANS FOR THE CHURCH OF S. LORENZO AT FLORENCE--MICHELANGELO'S LIFE AT CARRARA. 1513-1521. VIII. ADRIAN VI AND CLEMENT VII--THE SACRISTY AND LIBRARY OF S. LORENZO. 1521-1526. page 2 / 658 IX. SACK OF ROME AND SIEGE OF FLORENCE--MICHELANGELO'S FLIGHT TO VENICE--HIS RELATIONS TO THE MEDICI. 1527-1534. X. ON MICHELANGELO AS ARCHITECT. XI. FINAL SETTLEMENT IN ROME--PAUL III.--THE LAST JUDGMENT AND THE PAOLINE CHAPEL--THE TOMB OF JULIUS.