The Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery Act of 2016: an Ineffective Remedy for Returning Nazi-Looted Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sturm Und Drang : JONAS BURGERT at BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY DAFYDD JONES : JONAS BURGERT at JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN

FREE 16 HOT & COOL ART : JONAS BURGERT AT BLAIN SOUTHERN GALLERY : JONAS BURGERT AT Sturm und Drang DAFYDD JONES JONAS BURGERT I BERLIN STATE 11 www.state-media.com 1 THE ARCHERS OF LIGHT 8 JAN - 12 FEB 2015 ALBERTO BIASI | WALDEMAR CORDEIRO | CARLOS CRUZ-DÍEZ | ALMIR MAVIGNIER FRANÇOIS MORELLET | TURI SIMETI | LUIS TOMASELLO | NANDA VIGO Luis Tomasello (b. 1915 La Plata, Argentina - d. 2014 Paris, France) Atmosphère chromoplastique N.1016, 2012, Acrylic on wood, 50 x 50 x 7 cm, 19 5/8 x 19 5/8 x 2 3/4 inches THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING: 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ CAREL VISSER, 18 FEB - 10 APR 2015 TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com JAN_AD(STATE).indd 1 03/12/2014 10:44 WiderbergAd.State3.awk.indd 1 09/12/2014 13:19 rosenfeld porcini 6th febraury - 21st march 2015 Ali BAnisAdr 11 February – 21 March 2015 4 Hanover Square London, W1S 1BP Monday – Friday: 10.00 – 18.00 Saturday: 10.00 – 17.0 0 www.blainsouthern.com +44 (0)207 493 4492 >> DIARY NOTES COVER IMAGE ALL THE FUN OF THE FAIR IT IS A FACT that the creeping stereotyped by the Wall Street hedge-fund supremo or Dafydd Jones dominance of the art fair in media tycoon, is time-poor and no scholar of art history Jonas Burgert, 2014 the business of trading art and outside of auction records. The art fair is essentially a Photographed at Blain|Southern artists is becoming a hot issue. -

How Republic of Austria V. Altmann and United States V. Portrait of Wally Relay the Past and Forecast the Future of Nazi Looted Art Restitution Litigation Shira T

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 34 | Issue 3 Article 6 2008 How Republic of Austria v. Altmann and United States v. Portrait of Wally Relay the Past and Forecast the Future of Nazi Looted Art Restitution Litigation Shira T. Shapiro Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Shapiro, Shira T. (2008) "How Republic of Austria v. Altmann and United States v. Portrait of Wally Relay the Past and Forecast the Future of Nazi Looted Art Restitution Litigation," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 34: Iss. 3, Article 6. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol34/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Shapiro: How Republic of Austria v. Altmann and United States v. Portrait 5. SHAPIRO - ADC 4/30/2008 3:15:48 PM CASE NOTE: HOW REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA V. ALTMANN AND UNITED STATES V. PORTRAIT OF WALLY RELAY THE PAST AND FORECAST THE FUTURE OF NAZI LOOTED- ART RESTITUTION LITIGATION Shira T. Shapiro† I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................1148 II. THE BASIS FOR NAZI LOOTED-ART LITIGATION: HITLER’S CULTURAL OBSESSION.........................................................1150 III. THE UNITED STATES V. PORTRAIT OF WALLY, A PAINTING BY EGON SCHIELE LITIGATION ...................................................1154 IV. THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA V. ALTMANN DECISION: RECLAIMING GUSTAV KLIMT................................................1159 A. Initiation of Legal Proceedings........................................ -

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected]. -

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

JKV Offers All Residents and Staff Chance for COVID-19 Vaccination

March 2021 Vol. 8, Number 12 A Life-Plan Continuing Care Retirement Community Published Monthly by John Knox Village • 651 S.W. Sixth Street, Pompano Beach, Florida 33060 In This Month’s Issue JKV Offers All Residents And Staff Thanks For Asking ............... 2 Chance For COVID-19 Vaccination Rescuing Europe’s Art ....... 3 Chef Mark’s In Good Taste Recipe ........................ 4 Book Review ..................... 4 Meet The Middletons .......... 5 Ask Kim About JKV ............ 6 The Stressless Move .......... 7 Food As Medicine ................. 8 The Curious Mind ................. 8 JKV staff members (L. to R.) Susanne Russell, Joanne Avis and Loli Pire-Schmidt check-in resident Andrea Hipskind for her initial COVID-19 vaccination on Jan. 19. In all, some 800 residents and employees received their first vaccinations that day. Marty Lee photo. Technology Training ............ 9 ver since December and the management team jumped into action to plan for this ma- JKV Expands ........................ 9 Marty Lee approval of both the Pfizer- jor health care event. Elders in the Meaningful Life homes Gazette Contributor E A General’s Thoughts ...... 10 BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 including Assisted Living at Gardens West and Long-Term vaccines, people all over the nation Care in Seaside Cove and The Woodlands had already Find The Light ................. 10 have been seeking their turn for vaccinations. Subsequently, received their vaccinations, so the planning would involve the state of Florida prioritized persons 65 years of age and vaccinations for the entire community of more than 600 In- NSU Art Museum ............... 11 older, plus health care personnel with direct patient contact dependent Living residents and more than 600 employees. -

Michael Cowan Fitzgerald

1 Michael C. FitzGerald Office: 113 Hallden Hall tel. 860-297-2503 [email protected] [email protected] (home) EDUCATION 1976-1987 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Ph.D., M.Phil., M.A. DISSERTATION: "Pablo Picasso's Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire: Surrealism and Monumental Sculpture in France, 1918-1959." 1984-1986 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS M.B.A. 1972-1976 STANFORD UNIVERSITY B.A. EMPLOYMENT TRINITY COLLEGE (Hartford, CT) DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS 2007- Professor 2OO2-5 Director, Art History Program (first appointment) 1994-2007 Associate Professor, Department of Fine Arts 1996-1998 Chairman 1988-1994 Assistant Professor 1986-1988 CHRISTIE, MANSON AND WOODS INTERNATIONAL (New York, NY) Specialist-in-charge of Drawings, Department of Impressionist and Modern Art 1981-1983 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY (New York, NY) Preceptor,Department of Art History and Archaeology CONSULTANCY Research Director, Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz- Picasso para el Arte (FABA), 2020- AWARDS American Academy in Rome, April 2020 (deferred due to Corona Virus) Terra Foundation, 2006 2 National Endowment for the Arts, 2005-06 Faculty Research Leave, Trinity College, 2001-2002 3-Year Expense Grant, Trinity College, 2001-2004 Archives Grant, New York State Council of the Arts, 1999-2000 (with Whitney Museum of American Art) Fellowship, National Endowment for the Humanities, 1994-95 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer 1993 Travel to Collections Grant, National Endowment for the Humanities, Summer 1991 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer l989 Rudolf Wittkower Fellowship, Columbia University, 1980-81 Travel Grant, Columbia University, Summer l982; President's Fellowship, Columbia University, l977-78 CURRENT PROJECT Curator, Picasso and Classcial Traditions, This exhibition is a collaboration between the Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla and the Museo Picasso Málaga. -

The Marshall Plan in Austria 69

CAS XXV CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIANAUSTRIAN STUDIES STUDIES | VOLUME VOLUME 25 25 This volume celebrates the study of Austria in the twentieth century by historians, political scientists and social scientists produced in the previous twenty-four volumes of Contemporary Austrian Studies. One contributor from each of the previous volumes has been asked to update the state of scholarship in the field addressed in the respective volume. The title “Austrian Studies Today,” then, attempts to reflect the state of the art of historical and social science related Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.) • Austrian Studies Today studies of Austria over the past century, without claiming to be comprehensive. The volume thus covers many important themes of Austrian contemporary history and politics since the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1918—from World War I and its legacies, to the rise of authoritarian regimes in the 1930s and 1940s, to the reconstruction of republican Austria after World War II, the years of Grand Coalition governments and the Kreisky era, all the way to Austria joining the European Union in 1995 and its impact on Austria’s international status and domestic politics. EUROPE USA Austrian Studies Studies Today Today GünterGünter Bischof,Bischof, Ferdinand Ferdinand Karlhofer Karlhofer (Eds.) (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Studies Today Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 25 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2016 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

Michelangelo Buonarroti Artstart – 3 Dr

Michelangelo Buonarroti ArtStart – 3 Dr. Hyacinth Paul https://www.hyacinthpaulart.com/ The genius of Michelangelo • Renaissance era painter, sculptor, poet & architect • Best documented artist of the 16th century • He learned to work with marble, a chisel & a hammer as a young child in the stone quarry’s of his father • Born 6th March, 1475 in Caprese, Florence, Italy • Spent time in Florence, Bologna & Rome • Died in Rome 18th Feb 1564, Age 88 Painting education • Did not like school • 1488, age 13 he apprenticed for Domenico Ghirlandaio • 1490-92 attended humanist academy • Worked for Bertoldo di Giovanni Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Sistine Chapel Ceiling – (1508-12) Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo Doni Tondo (Holy Family) (1506) – Uffizi, Florence Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Creation of Adam (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Last Judgement - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo Ignudo (1509) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Drunkenness of Noah - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Deluge - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The First day of creation - - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Prophet Jeremiah - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The last Judgement - (1508-12) – Vatican, Rome Famous paintings of Michelangelo The Crucifixion of St. Peter - (1546-50) – Vatican, Rome Only known Self Portrait Famous paintings of Michelangelo -

Nazi-Looted Art Litigation

KREDER FINAL COPY.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 11/27/2012 11:49 AM Fighting Corruption of the Historical Record: Nazi-Looted Art Litigation Jennifer Anglim Kreder For the first time in history, restitution may be expected to continue for as long as works of art known to have been plundered during a war continue to be rediscovered. —Ardelia R. Hall1 I. INTRODUCTION Over the years, with a few praiseworthy exceptions, U.S. courts have dismissed many claims to recover Nazi-looted art on technical grounds, causing distortion of the historical record.2 This trend seems to reflect bias against these historical claims arising from a lack of historical knowledge.3 Tales of venerated institutions,4 such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), acquiring what they knew or should have known was trafficked and laundered art may seem outrageous to those unaware of the infection of the market with art that had been stolen or extorted from Jews between 1933 and 1945. Even when judges recognize the plausibility of such claims,5 attending to them requires judicial fortitude and dedication to sorting Associate Dean for Faculty Development and Professor of Law, Salmon P. Chase College of Law, Northern Kentucky University; J.D., Georgetown University Law Center. The views expressed in this Article are those of the author only and are not necessarily those of the Kansas Law Review, Inc., its editors, or staff. 1. Ardelia R. Hall, The Recovery of Cultural Objects Dispersed During World War II, 25 DEP’T ST. BULL. 337, 339 (1951). 2. See infra Appendix A, Federal Holocaust-Era Art Claims Since 2004 (Oct. -

Fighting Corruption of the Historical Record: Nazi-Looted Art Litigation

Fighting Corruption of the Historical Record: Nazi-Looted Art Litigation Jennifer Anglim Kreder* For the first time in history, restitution may be expected to continuefor as long as works of art known to have been plundered during a war continue to be rediscovered. -Ardelia R. Hall' I. INTRODUCTION Over the years, with a few praiseworthy exceptions, U.S. courts have dismissed many claims to recover Nazi-looted art on technical grounds, causing distortion of the historical record.2 This trend seems to reflect bias against these historical claims arising from a lack of historical knowledge. Tales of venerated institutions, such as the Museum of Modem Art (MoMA), acquiring what they knew or should have known was trafficked and laundered art may seem outrageous to those unaware of the infection of the market with art that had been stolen or extorted from Jews between 1933 and 1945. Even when judges recognize the plausibility of such claims,s attending to them requires judicial fortitude and dedication to sorting . Associate Dean for Faculty Development and Professor of Law, Salmon P. Chase College of Law, Northern Kentucky University; J.D., Georgetown University Law Center. The views expressed in this Article are those of the author only and are not necessarily those of the Kansas Law Review, Inc., its editors, or staff. 1. Ardelia R. Hall, The Recovery of Cultural Objects Dispersed During World War [1, 25 DEP'T ST. BULL. 337, 339 (1951). 2. See infra Appendix A, Federal Holocaust-Era Art Claims Since 2004 (Oct. 26, 2012) [hereinafter App. A]. 3. See infra Part II (detailing how judicial decision-making is prone to bias against Holocaust- era claims). -

Annual Report 2003 Annual Report 2003

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2003 ANNUAL REPORT 2003 1 ARcover2003.p65 1 6/1/2004, 11:41 PM Annual Report 2003 ARpp01-21.p65 1 6/1/2004, 11:45 PM The Cleveland Cover: School The Annual Report The type is Bembo right in the United 46, 68, 72, 82, 87, 92, Museum of Art children are enthralled was produced by the and TheSans adapted States of America or 100; Becky Bristol: p. 11150 East with the ten litho- External Affairs for this publication. abroad and may not 95; Philip Brutz: pp. Boulevard graphs in Color division of the Composed with be reproduced in any 90 (right), 96; © Cleveland, Ohio Numeral Series (cour- Cleveland Museum of Adobe PC form or medium Disney/Pixar: p. 94; 44106-1797 tesy Margo Leavin Art. PageMaker 6.5. without permission Gregory M. Donley: Copyright © 2004 Gallery, Los Angeles), Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: from the copyright pp. 9 (left), 12, 13, on view in the holders. The follow- 37, 39, 44 (top), 45 The Cleveland M. Donley Works of art in the Museum of Art landmark exhibition ing photographers are (bottom), 47 (bot- Jasper Johns: Numbers. Editing: Barbara J. collection were pho- acknowledged: tom), 49 (top), 67, All rights reserved. Bradley and Kathleen tographed by museum Frontispiece: The Howard Agresti: pp. 71, 77, 79, 80, 89 No portion of this Mills photographers 1, 7, 8 (all), 10 (both), (all); Ann Koslow: p. publication may be museum and lagoon Howard Agriesti and in winter. Design: Thomas H. 36, 38, 40, 43, 44 71 (left); Shannon reproduced in any Barnard Gary Kirchenbauer; (middle and bottom), Masterson: p. -

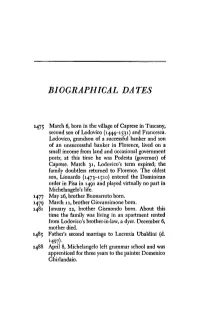

Biographical Dates

BIOGRAPHICAL DATES 1475 March 6, born in the village of Caprese in Tuscany, second son of Lodovico (1444-1531) and Francesca. Lodovico, grandson of a successful banker and son of an unsuccessful banker in Florence, lived on a small income from land and occasional government posts; at this time he was Podesta (governor) of Caprese. March 31, Lodovico's term expired; the family doubtless returned to Florence. The oldest son, Lionardo (1473-1510) entered the Dominican order in Pisa in 1491 and played virtually no part in Michelangelo's life. 1477 May 26, brother Buonarroto bom. 1479 March 11, brother Giovansimone born. 1481 January 22, brother Gismondo bom. About this time the family was living in an apartment rented from Lodovico's brother-in-law, a dyer. December 6, mother died. 1485 Father's second marriage to Lucrezia Ubaldini (d. M97)- 1488 April 8, Michelangelo left grammar school and was apprenticed for three years to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio. MICHELANGELO [1] 1489 Left Ghirlandaio and studied sculpture in the gar- den of Lorenzo de' Medici the Magnificent. 1492 Lorenzo the Magnificent died, succeeded by his old- est son Piero. 1494 Rising against Piero de' Medici, who fled (d. 1503). Republic re-established under Savonarola. October, Michelangelo fled and after a brief stay in Venice went to Bologna. 1495 In Bologna, carved three small statues which brought to completion the tomb of St. Dominic. Returned to Florence, carved the Cupid, sold to Baldassare del Milanese, a dealer. 1496 June, went to Rome. Carved the Bacchus for the banker Jacopo Galli. 1497 November, went to Carrara to obtain marble.