The Holocaust, Museum Ethics and Legalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Participants

JUNE 26–30, Prague • Andrzej Kremer, Delegation of Poland, Poland List of Participants • Andrzej Relidzynski, Delegation of Poland, Poland • Angeles Gutiérrez, Delegation of Spain, Spain • Aba Dunner, Conference of European Rabbis, • Angelika Enderlein, Bundesamt für zentrale United Kingdom Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen, Germany • Abraham Biderman, Delegation of USA, USA • Anghel Daniel, Delegation of Romania, Romania • Adam Brown, Kaldi Foundation, USA • Ann Lewis, Delegation of USA, USA • Adrianus Van den Berg, Delegation of • Anna Janištinová, Czech Republic the Netherlands, The Netherlands • Anna Lehmann, Commission for Looted Art in • Agnes Peresztegi, Commission for Art Recovery, Europe, Germany Hungary • Anna Rubin, Delegation of USA, USA • Aharon Mor, Delegation of Israel, Israel • Anne Georgeon-Liskenne, Direction des • Achilleas Antoniades, Delegation of Cyprus, Cyprus Archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères et • Aino Lepik von Wirén, Delegation of Estonia, européennes, France Estonia • Anne Rees, Delegation of United Kingdom, United • Alain Goldschläger, Delegation of Canada, Canada Kingdom • Alberto Senderey, American Jewish Joint • Anne Webber, Commission for Looted Art in Europe, Distribution Committee, Argentina United Kingdom • Aleksandar Heina, Delegation of Croatia, Croatia • Anne-Marie Revcolevschi, Delegation of France, • Aleksandar Necak, Federation of Jewish France Communities in Serbia, Serbia • Arda Scholte, Delegation of the Netherlands, The • Aleksandar Pejovic, Delegation of Monetenegro, Netherlands -

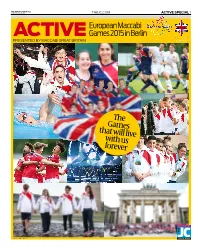

The Games That Will Live with Us Forever

THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 1 European Maccabi ACTIVE Games 2015 in Berlin PRESENTED BY MACCABI GREAT BRITAIN The Games that will live with us forever MEDIA partner PHOTOS: MARC MORRIS THE JEWISH CHRONICLE THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 2 ACTIVE SPECIAL THEJC.COM 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 3 ALL ALL WORDS PHOTOS WELCOME BY DAnnY BY MARC CARO MORRIS Maccabi movement’s ‘miracle’ in Berlin LDN Investments are proud to be associated with Maccabi GB and the success of the European Maccabi Games in Berlin. HIS SUMMER, old; athletes and their families; reuniting THE MACCABI SPIRIT place where they were banished from first night at the GB/USA Gala Dinner, “By SOMETHING hap- existing friendships and creating those Despite the obvious emotion of the participating in sport under Hitler’s winning medals we have not won. By pened which had anew. Friendships that will last a lifetime. Opening Ceremony, the European Mac- reign was a thrill and it gave me an just being here in Berlin we have won.” never occurred But there was also something dif- cabi Games 2015 was one big party, one enormous sense of pride. We will spread the word, keep the before. For the first ferent about these Games – something enormous celebration of life and of Having been there for a couple of days, torch of love, not hate, burning bright. time in history, the that no other EMG has had before it. good triumphing over evil. Many thou- my hate of Berlin turned to wonder. -

MS 315 A1076 Papers of Clemens Nathan Scrapbooks Containing

1 MS 315 A1076 Papers of Clemens Nathan Scrapbooks containing newspaper cuttings, correspondence and photographs from Clemens Nathan’s work with the Anglo-Jewish Association (AJA) 1/1 Includes an obituary for Anatole Goldberg and information on 1961-2, 1971-82 the Jewish youth and Soviet Jews 1/2 Includes advertisements for public meetings, information on 1972-85 the Middle East, Soviet Jews, Nathan’s election as president of the Anglo-Jewish Association and a visit from Yehuda Avner, ambassador of the state of Israel 1/3 Including papers regarding public lectures on human rights 1983-5 issues and the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, the Middle East, human rights and an obituary for Leslie Prince 1/4 Including papers regarding the Anglo-Jewish Association 1985-7 (AJA) president’s visit to Israel, AJA dinner with speaker Timothy Renton MP, Minister of State for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office; Kurt Waldheim, president of Austria; accounts for 1983-4 and an obituary for Viscount Bearsted Papers regarding Nathan’s work with the Consultative Council of Jewish Organisations (CCJO) particularly human rights issues and printed email correspondence with George R.Wilkes of Gonville and Cauis Colleges, Cambridge during a period when Nathan was too ill to attend events and regarding the United Nations sub- commission on human right at Geneva. [The CCJO is a NGO (Non-Governmental Organisation) with consultative status II at UNESCO (the United National Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation)] 2/1 Papers, including: Jan -Aug 1998 arrangements -

Expert Report by Professor Richard Evans (2000)

Expert Report by Professor Richard Evans (2000) IRVING VS. (1) LIPSTADT AND (2) PENGUIN BOOKS EXPERT WITNESS REPORT BY RICHARD J. EVANS FBA Professor of Modern History, University of Cambridge Warning: This title page does not belong to the original report. The original report starts on the second page which is to be considered page number 1. IRVING VS. (1) LIPSTADT AND (2) PENGUIN BOOKS EXPERT W ITNESS REPORT BY RICHARD J. EVANS FBA Professor of Modern History, University of Cambridge Contents 1. Introduction 3 1.1 Purpose of this Report 3 1.2 Material Instructions 4 1.3 Author of the Report 4 1.4 Curriculum vitae 9 1.5 Methods used to draw up this Report 14 1.6 Argument and structure of the Report 19 2. Irving the historian 26 2.1 Publishing career 26 2.2 Qualifications 28 2.3 Professional historians and archival research 29 2.4 Documents and sources 35 2.5 Reputation 41 2.6 Conclusion 64 3. Irving and Holocaust denial66 3.1 Definitions of ‘The Holocaust’ 67 3.2 Holocaust denial 77 3.3 The arguments before the court 87 (a) Lipstadt’s allegations and Irving’s replies 87 (b) The 1977 edition of Hitler’s War 89 (c) The 1991 edition of Hitler’s War 92 (d) Irving’s biography of Hermann Göring 100 (e) Conclusion 103 3.4 Irving and the central tenets of Holocaust denial 106 (a) Numbers of Jews killed 106 (b) Use of gas chambers 126 (c) Systematic nature of the extermination 134 (d) Evidence for the Holocaust 140 (e) Conclusion 173 3.5 Connections with Holocaust deniers 174 (a) The Institute for Historical Review 174 (b) Other Holocaust deniers 190 3.6 Conclusion 200 4. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

Holocaust-Denial Literature: a Fourth Bibliography

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research York College 2000 Holocaust-Denial Literature: A Fourth Bibliography John A. Drobnicki CUNY York College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/yc_pubs/25 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Holocaust-Denial Literature: A Fourth Bibliography John A. Drobnicki This bibliography is a supplement to three earlier ones published in the March 1994, Decem- ber 1996, and September 1998 issues of the Bulletin of Bibliography. During the intervening time. Holocaust revisionism has continued to be discussed both in the scholarly literature and in the mainstream press, especially owing to the libel lawsuit filed by David Irving against Deb- orah Lipstadt and Penguin Books. The Holocaust deniers, who prefer to call themselves “revi- sionists” in an attempt to gain scholarly legitimacy, have refused to go away and remain as vocal as ever— Bradley R. Smith has continued to send revisionist advertisements to college newspapers (including free issues of his new publication. The Revisionist), generating public- ity for his cause. Holocaust-denial, which will be used interchangeably with Holocaust revisionism in this bib- liography, is a body of literature that seeks to “prove” that the Jewish Holocaust did not hap- pen. Although individual revisionists may have different motives and beliefs, they all share at least one point: that there was no systematic attempt by Nazi Germany to exterminate Euro- pean Jewry. -

How Republic of Austria V. Altmann and United States V. Portrait of Wally Relay the Past and Forecast the Future of Nazi Looted Art Restitution Litigation Shira T

William Mitchell Law Review Volume 34 | Issue 3 Article 6 2008 How Republic of Austria v. Altmann and United States v. Portrait of Wally Relay the Past and Forecast the Future of Nazi Looted Art Restitution Litigation Shira T. Shapiro Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr Recommended Citation Shapiro, Shira T. (2008) "How Republic of Austria v. Altmann and United States v. Portrait of Wally Relay the Past and Forecast the Future of Nazi Looted Art Restitution Litigation," William Mitchell Law Review: Vol. 34: Iss. 3, Article 6. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/wmlr/vol34/iss3/6 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in William Mitchell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Shapiro: How Republic of Austria v. Altmann and United States v. Portrait 5. SHAPIRO - ADC 4/30/2008 3:15:48 PM CASE NOTE: HOW REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA V. ALTMANN AND UNITED STATES V. PORTRAIT OF WALLY RELAY THE PAST AND FORECAST THE FUTURE OF NAZI LOOTED- ART RESTITUTION LITIGATION Shira T. Shapiro† I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................1148 II. THE BASIS FOR NAZI LOOTED-ART LITIGATION: HITLER’S CULTURAL OBSESSION.........................................................1150 III. THE UNITED STATES V. PORTRAIT OF WALLY, A PAINTING BY EGON SCHIELE LITIGATION ...................................................1154 IV. THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA V. ALTMANN DECISION: RECLAIMING GUSTAV KLIMT................................................1159 A. Initiation of Legal Proceedings........................................ -

1 Antisemitism Rosh Hashanah 5780 September 29, 2019 Rabbi David

Antisemitism Rosh Hashanah 5780 September 29, 2019 Rabbi David Stern Tonight marks my thirty-first High Holidays at Temple Emanu-El, a huge blessing in my life. In thirty-one years of high holiday sermons, you have been very forgiving, and I have addressed a diverse array of topics: from our internal spiritual journeys to Judaism’s call for justice in the world; relationship and forgiveness, immigration and race, prayer and faith, loving Israel and loving our neighbors; birth and death and just about everything in between in this messy, frustrating, promising, profound, sacred realm we call life. Except -- in thirty-one years as a Jewish leader, I have not given a single High Holiday sermon about antisemitism.1 References, allusions, a pointed paragraph here and there, yes. But in three decades of High Holiday sermons spanning the end of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first centuries, not a single one about antisemitism. I’m hoping that doesn’t constitute professional malpractice, but it is strange. So I’ve asked myself why. Reason #1: I had almost no experience of antisemitism growing up. With one limited exception, I never even experienced name-calling, let alone any physical incident. All four of my grandparents were born in America, and our story was the classic trajectory of American Jewish integration and success. 1 Professor Deborah E. Lipstadt makes a compelling argument for this spelling. Lipstadt rejects the hyphen in the more conventional “Anti-Semitism” because it implies that whatever lies to the right of the hyphen exists as an independent entity. -

Robert Jan Van Pelt Auschwitz, Holocaust-Leugnung Und Der Irving-Prozess

ROBERT JAN VAN PELT AUSCHWITZ, HOLOCAUST-LEUGNUNG UND DER IRVING-PROZESS Robert Jan van Pelt Auschwitz, Holocaust-Leugnung und der Irving-Prozess In 1987 I decided to investigate the career and fate of the came an Ortsgeschichte of Auschwitz. This history, publis- architects who had designed Auschwitz. That year I had hed as Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present (1996), tried to re- obtained a teaching position at the School of Architecture create the historical context of the camp that had been of of the University of Waterloo in Canada. Considering the relevance to the men who created it. In 1939, at the end of question of the ethics of the architectural profession, I be- the Polish Campaign, the Polish town of Oswiecim had came interested in the worst crime committed by archi- been annexed to the German Reich, and a process of eth- tects. As I told my students, “one can’t take a profession nic cleansing began in the town and its surrounding coun- seriously that hasn’t insisted that the public authorities tryside that was justified through references to the medie- hang one of that profession’s practitioners for serious pro- val German Drang nach Osten. Also the large-scale and fessional misconduct.” I knew that physicians everywhere generally benign “Auschwitz Project,” which was to lead had welcomed the prosecution and conviction of the doc- to the construction of a large and beautiful model town of tors who had done medical experiments in Dachau and some 60,000 inhabitants supported by an immense synthe- other German concentration camps. -

Holocaust Narratives and Their Impact: Personal Identification and Communal Roles Hannah Kliger, Bea Hollander-Goldfein, and Emilie S

LITJCS001prelspi-xiv 25.03.2008 09:58am Page iii Jewish Cultural Studies volume one Jewishness: Expression, Identity, and Representation Edited by SIMON J. BRONNER Offprint Oxford . Portland, Oregon The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization 2008 LITJCS06p151-174 28.01.2008 08:13pm Page 151 six Holocaust Narratives and their Impact: Personal Identification and Communal Roles hannah kliger, bea hollander-goldfein, and emilie s. passow Scholarly attention within the humanities and social sciences has con- verged on aspects of trauma and its aftermath, especially the effect of trauma on personal and cultural formations of identity. Studies that range in perspective from the anthropological, the sociological, and the historical to the literary, the psychological, and the philosophical examine the long-term consequences of the experience of trauma on human beings and how their constructions of traumatic memories shape the meanings they attribute to these events (Brenner 2004; Lifton 1993; Van der Kolk, McFarlane, and Weisaeth 1996). Researchers from a variety of perspectives have investigated the history of the concept of trauma, and have offered their observations on the impact of overwhelming life experiences on those affected by genocidal persecution (Caruth 1996; Leys 2000). For the Jewish historical and cultural narrative, particularly of the last century, the experience of trauma and dislocation is communicated on two levels, as fam- ily discourse and as communal oral history. Friesel (1994) has noted the ways in which the Holocaust affects contemporary Jewish consciousness. Bar-On (1999) describes the interpretative strategies that survivors and their children employ to communicate real and imagined lessons of the Holocaust. From these and other studies, the forms of recording and transmitting the experiences of Jewish Holo- caust survivors offer lessons in the modes of adaptation and meaning-making in the aftermath of trauma. -

Sprawuj Się (Do Good): Using the Experience of Holocaust Rescuers to Teach Public Service Values

SPRAWUJ SIĘ (DO GOOD): USING THE EXPERIENCE OF HOLOCAUST RESCUERS TO TEACH PUBLIC SERVICE VALUES ARTICLE * CHRISTINA A. ZAWISZA Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1051 I. Krakow Conference Theme: Lawlessness and the Holocaust ......................... 1056 II. The Therapeutic Jurisprudence Framework ................................................... 1059 A. TJ Principles ............................................................................................... 1060 B. TJ Techniques and Methodologies ........................................................... 1061 III. Attributes of the Altruists in the Holocaust .................................................. 1064 A. Individual Rescuers.................................................................................... 1065 B. Group Rescuers .......................................................................................... 1067 C. Why Would the Altruists Do What They Did? ........................................ 1068 IV. Rewinding and Reframing the Krakow Conference Through a Therapeutic Jurisprudence Lens ..................................................................... 1072 V. Teaching Professional Service Values from this Rewound and Reframed Lens .................................................................................................. 1075 A. Attributes of the Millennial Generation ................................................... 1075 Conclusion ............................................................................................................ -

Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived Despite All Odds, They Survived, Persisted — and Thrived

The Hidden® Child VOL. XXVII 2019 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION /ADL DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED DESPITE ALL ODDS, THEY SURVIVED, PERSISTED — AND THRIVED FROM HUNTED ESCAPEE TO FEARFUL REFUGEE: POLAND, 1935-1946 Anna Rabkin hen the mass slaughter of Jews ended, the remnants’ sole desire was to go 3 back to ‘normalcy.’ Children yearned for the return of their parents and their previous family life. For most child survivors, this wasn’t to be. As WEva Fogelman says, “Liberation was not an exhilarating moment. To learn that one is all alone in the world is to move from one nightmarish world to another.” A MISCHLING’S STORY Anna Rabkin writes, “After years of living with fear and deprivation, what did I imagine Maren Friedman peace would bring? Foremost, I hoped it would mean the end of hunger and a return to 9 school. Although I clutched at the hope that our parents would return, the fatalistic per- son I had become knew deep down it was improbable.” Maren Friedman, a mischling who lived openly with her sister and Jewish mother in wartime Germany states, “My father, who had been captured by the Russians and been a prisoner of war in Siberia, MY LIFE returned to Kiel in 1949. I had yearned for his return and had the fantasy that now that Rivka Pardes Bimbaum the war was over and he was home, all would be well. That was not the way it turned out.” Rebecca Birnbaum had both her parents by war’s end. She was able to return to 12 school one month after the liberation of Brussels, and to this day, she considers herself among the luckiest of all hidden children.