Federicobaroccilookinside.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For a History of the Use of the Antoninian Baths: Owners, Excavations and Dispossession

ArcHistoR anno VII (2020) n. 13 For a History of the Use of the Antoninian Baths: Owners, Excavations and Dispossession Isabella Salvagni For centuries, the monumental ruins of the Baths of Caracalla in Rome have attracted the attention of humanists, philologists and antique dealers, tickling their curiosity and arousing imaginative reconstructions. From the forefathers to the spokespersons of modern archaeology, it is this discipline that has mostly directed and guided the most recent studies on the complex, from the 1800s to today. However, while the ‘archaeological’ vocation constitutes the most evident and representative essence of these remains, for over a thousand years the whole area over which they lay was mainly used as agricultural land divided and passed on from hand to hand through countless owners. An attempt is made to provide a brief overview of this long and little-known history of use, covering the 300 years from the mid-16th century to the Unification of Italy. Starting from the identification of some of the many figures who have alternated over time as owners of the individual estates in different capacities, the story gives us a valuable amount of information also relating to what the owners themselves, as customers, have deliberated and conducted on the farms which they used, cultivating them, building and directing stripping, excavation, accommodation, reuse, and destruction operations, while providing us with useful data for the analysis of the transformative mechanisms of the land use of this portion of the city, to be related to the more general urban history of Rome. AHR VII (2020) n. -

VILLA I TAT TI Via Di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy

The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies VILLA I TAT TI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy Volume 30 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.it Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 Autumn 2010 or the eighth and last time, I fi nd Letter from Florence to see art and science as sorelle gemelle. Fmyself sitting on the Berenson gar- The deepening shadows enshroud- den bench in the twilight, awaiting the ing the Berenson bench are conducive fi reworks for San Giovanni. to refl ections on eight years of custodi- In this D.O.C.G. year, the Fellows anship of this special place. Of course, bonded quickly. Three mothers and two continuities are strong. The community fathers brought eight children. The fall is still built around the twin principles trip took us to Rome to explore the scavi of liberty and lunch. The year still be- of St. Peter’s along with some medieval gins with the vendemmia and the fi ve- basilicas and baroque libraries. In the minute presentation of Fellows’ projects, spring, a group of Fellows accepted the and ends with a nostalgia-drenched invitation of Gábor Buzási (VIT’09) dinner under the Tuscan stars. It is still a and Zsombor Jékeley (VIT’10) to visit community where research and conver- Hungary, and there were numerous visits sation intertwine. to churches, museums, and archives in It is, however, a larger community. Florence and Siena. There were 19 appointees in my fi rst In October 2009, we dedicated the mastery of the issues of Mediterranean year but 39 in my last; there will be 31 Craig and Barbara Smyth wing of the encounter. -

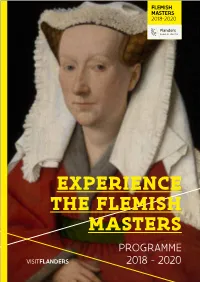

Experience the Flemish Masters Programme 2018 - 2020

EXPERIENCE THE FLEMISH MASTERS PROGRAMME 2018 - 2020 1 The contents of this brochure may be subject to change. For up-to-date information: check www.visitflanders.com/flemishmasters. 2 THE FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 AT THE PINNACLE OF ARTISTIC INVENTION FROM THE MIDDLE AGES ONWARDS, FLANDERS WAS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE FAMOUS ART MOVEMENTS OF THE TIME: PRIMITIVE, RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE. FOR A PERIOD OF SOME 250 YEARS, IT WAS THE PLACE TO MEET AND EXPERIENCE SOME OF THE MOST ADMIRED ARTISTS IN WESTERN EUROPE. THREE PRACTITIONERS IN PARTICULAR, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL AND RUBENS ROSE TO PROMINENCE DURING THIS TIME AND CEMENTED THEIR PLACE IN THE PANTHEON OF ALL-TIME GREATEST MASTERS. 3 FLANDERS WAS THEN A MELTING POT OF ART AND CREATIVITY, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, AND STILL TODAY IS A REGION THAT BUSTLES WITH VITALITY AND INNOVATION. The “Flemish Masters” project has THE FLEMISH MASTERS been established for the inquisitive PROJECT 2018-2020 traveller who enjoys learning about others as much as about him or The Flemish Masters project focuses Significant infrastructure herself. It is intended for those on the life and legacies of van Eyck, investments in tourism and culture who, like the Flemish Masters in Bruegel and Rubens active during are being made throughout their time, are looking to immerse th th th the 15 , 16 and 17 centuries, as well Flanders in order to deliver an themselves in new cultures and new as many other notable artists of the optimal visitor experience. In insights. time. addition, a programme of high- quality events and exhibitions From 2018 through to 2020, Many of the works by these original with international appeal will be VISITFLANDERS is hosting an Flemish Masters can be admired all organised throughout 2018, 2019 abundance of activities and events over the world but there is no doubt and 2020. -

Download Artwork Tear Sheet

Federico Barocci (Urbino, 1535 – Urbino, 1612) Man Reading, c. 1605–1607 Oil on canvas (old relining) 65.5 x 49.5 cm On the back, label printed in red ink: Emo / Gio Battist[a] Provenance – Collection of Cardinal Antonio Barberini. Inventory 1671: "130 – Un quadro di p.mi 3 ½ inc.a di Altezza, e p.mi 3 di largha’ Con Mezza figura con il Braccio incupido [incompiuto] appogiato al capo, e nell’altra Un libro, opera di Lodovico [sic] Barocci Con Cornice indorata n° 1-130" – Paris, Galerie Tarantino until 2018 Literature – Andrea Emiliani, "Federico Barocci. Étude d’homme lisant", in exh. cat. Rome de Barocci à Fragonard (Paris: Galerie Tarantino, 2013), pp. 18–21, repr. – Andrea Emiliani, La Finestra di Federico Barocci. Per una visione cristologica del paesaggio urbano, Bologne (Faenza: Carta Bianca, 2016), p. 118, repr. Trained in the Mannerist tradition in Urbino and Rome, Federico Barocci demonstrated from the outset an astonishing capacity to assimilate the art of the masters. Extracting the essentials from a pantheon comprising Raphael, the Venetians and Correggio, he perfected a language at once profoundly personal and attuned to the issues raised by the Counter-Reformation. After an initial grounding in his native Urbino by Battista Franco and his uncle, Bartolommeo Genga, he went to Rome under the patronage of Cardinal della Rovere and studied Raphael while working with Taddeo Zuccaro. During a second stay in Rome in 1563 he was summoned by Pope Pius VI to help decorate the Casino del Belvedere at the Vatican, but in the face of the hostility his success triggered on the Roman art scene he ultimately fled the city – the immediate cause, it was said, being an attempted poisoning by rivals whose aftereffects were with him for the rest of his life. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

Romacultura Agosto 2016

ROMACULTURA AGOSTO 2016 La Chiesa e l’Ospedale dei Genovesi Il magico e il sacro a Trastevere ricordando la peste ROMACULTURA Ma il problema è l’alcool Registrazione Tribunale di Roma n.354/2005 DIRETTORE RESPONSABILE Passeggiate: Tra le Serviane e le Aureliane Stefania Severi RESPONSABILE EDITORIALE Claudia Patruno La chiesa e l’ospedale dei “tignosi” CURATORE INFORMAZIONI D’ARTE Gianleonardo Latini La Mongolia non è solo Gengis Khan EDITORE Hochfeiler via Moricone, 14 00199 Roma Imperatori restaurati ai Capitolini Tel. 39 0662290594/549 www.hochfeiler.it Felix Austria San Cosimato: Da monastero ad ospedale La Spina: Oltre due millenni di storia 1 Pagina ROMA CULTURA Registrazione Tribunale di Roma n.354/2005 Edizioni Hochfeiler ……………… LA CHIESA E L’OSPEDALE DEI GENOVESI In via Anicia, in Trastevere, dietro l’abside della chiesa di Santa Cecilia fiancheggia la strada un edificio che comprende la facciata di una chiesa di non grandi dimensioni e un muro, con un bel portale, che racchiude l’antico ospedale dei Genovesi. Il complesso fu edificato negli ultimi due decenni del ‘400 per la munificenza di un mercante di Genova, Medialuce Cicala, che decise di assistere i suoi connazionali in difficoltà. All’epoca il porto fluviale di Roma era situato nella zona dove ora si trova l’Ospizio del San Michele; intorno all’approdo gravitava una svariata umanità di mercanti, marinai, pescatori, barcaioli, facchini, osti, locandieri e tra loro erano numerosi i cittadini della Repubblica di Genova Il Cicala lasciò i suoi beni legandoli alla costruzione di una chiesa e di un ospedale destinati ad accogliere i suoi connazionali malati; l’ospedale fu edificato dopo il 1482 mentre la chiesa, dedicata a San Giovanni Battista, è citata dalle fonti la prima volta nel 1492. -

La Rinascita Dell'arte Musiva in Epoca Moderna

La rinascita dell’arte musiva in epoca moderna in Europa. La tradizione del mosaico in Italia, in Spagna e in Inghilterra Ottobrina Voccoli ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. -

Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities

National Gallery of Art Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities ~ .~ I1{, ~ -1~, dr \ --"-x r-i>- : ........ :i ' i 1 ~,1": "~ .-~ National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Center 5 Research Reports and Record of Activities June 1984---May 1985 Washington, 1985 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, D.C. 20565 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without thc written permission of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20565. Copyright © 1985 Trustees of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This publication was produced by the Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington. Frontispiece: Gavarni, "Les Artistes," no. 2 (printed by Aubert et Cie.), published in Le Charivari, 24 May 1838. "Vois-tu camarade. Voil~ comme tu trouveras toujours les vrais Artistes... se partageant tout." CONTENTS General Information Fields of Inquiry 9 Fellowship Program 10 Facilities 13 Program of Meetings 13 Publication Program 13 Research Programs 14 Board of Advisors and Selection Committee 14 Report on the Academic Year 1984-1985 (June 1984-May 1985) Board of Advisors 16 Staff 16 Architectural Drawings Advisory Group 16 Members 16 Meetings 21 Members' Research Reports Reports 32 i !~t IJ ii~ . ~ ~ ~ i.~,~ ~ - ~'~,i'~,~ ii~ ~,i~i!~-i~ ~'~'S~.~~. ,~," ~'~ i , \ HE CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS was founded T in 1979, as part of the National Gallery of Art, to promote the study of history, theory, and criticism of art, architecture, and urbanism through the formation of a community of scholars. -

La Chiesa E Il Quartiere Di San Francesco a Pisa

Edizioni dell’Assemblea 206 Ricerche Franco Mariani - Nicola Nuti La chiesa e il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa Giugno 2020 CIP (Cataloguing in Publication) a cura della Biblioteca della Toscana Pietro Leopoldo La chiesa e il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa / Franco Mariani, Nicola Nuti ; [presentazioni di Eugenio Giani, Michele Conti, Fra Giuliano Budau]. - [Firenze] : Consiglio regionale della Toscana, 2020 1. Mariani, Franco 2. Nuti, Nicola 3. Giani, Eugenio 4. Conti, Michele 5. Budau, Giuliano 726.50945551 Chiesa di San Francesco <Pisa> Volume in distribuzione gratuita In copertina: facciata della chiesa di San Francesco a Pisa del Sec. XIII, Monumento Nazionale e di proprietà dello Stato. Foto di Franco Mariani. Consiglio regionale della Toscana Settore “Rappresentanza e relazioni istituzionali ed esterne. Comunicazione, URP e Tipografia” Progetto grafico e impaginazione: Patrizio Suppa Pubblicazione realizzata dal Consiglio regionale della Toscana quale contributo ai sensi della l.r. 4/2009 Giugno 2020 ISBN 978-88-85617-66-7 Sommario Presentazioni Eugenio Giani, Presidente del Consiglio regionale della Toscana 11 Michele Conti, Sindaco di Pisa 13 Fra Giuliano Budau, Padre Guardiano, Convento di San Francesco a Pisa 15 Prologo 17 Capitolo I Il quartiere di San Francesco a Pisa 19 Capitolo II Viaggio all’interno del quartiere 29 Capitolo III L’arrivo dei Francescani a Pisa 33 Capitolo IV I Frati Minori Conventuali 45 Capitolo V L’Inquisizione 53 Capitolo VI La chiesa di San Francesco 57 Capitolo VII La chiesa nelle guide turistiche -

Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B. Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE ALBERTO ARINGHIERI AND THE CHAPEL OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST: PATRONAGE, POLITICS, AND THE CULT OF RELICS IN RENAISSANCE SIENA By TIMOTHY BRYAN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Timothy Bryan Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Timothy Bryan Smith defended on November 1 2002. Jack Freiberg Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Pietralunga Outside Committee Member Nancy de Grummond Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member Approved: Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History Sally McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the abovenamed committee members. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must thank the faculty and staff of the Department of Art History, Florida State University, for unfailing support from my first day in the doctoral program. In particular, two departmental chairs, Patricia Rose and Paula Gerson, always came to my aid when needed and helped facilitate the completion of the degree. I am especially indebted to those who have served on the dissertation committee: Nancy de Grummond, Robert Neuman, and Mark Pietralunga. -

SS History.Pages

History Sancta Sanctorum The chapel now known as the Sancta Sanctorum was the original private papal chapel of the mediaeval Lateran Palace, and as such was the predecessor of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. The popes made the Lateran their residence in the early 4th century as soon as the emperor Constantine had built the basilica, but the first reference to a private palace chapel dedicated to St Lawrence is in the entry in the Liber Pontificalis for Pope Stephen III (768-72). Pope Gregory IV (827-44) is recorded as having refitted the papal apartment next to the chapel. The entry for Pope Leo III (795-816) shows the chapel becoming a major store of relics. It describes a chest of cypress wood (arca cypressina) being kept here, containing "many precious relics" used in liturgical processions. The famous full-length icon of Christ Santissimo Salvatore acheropita was one of the treasures, first mentioned in the reign of Pope Stephen II (752-7) but probably executed in the 5th century. The name acheropita is from the Greek acheiropoieta, meaning "made without hands" because its legend alleges that St Luke began painting it and an angel finished it for him. The name of the chapel became the Sancta Sanctorum in the early 13th century because of these relics. Pope Innocent III (1198-1216) provided bronze reliquaries for the heads of SS Peter and Paul which were kept here then (they are now in the basilica), and also a silver-gilt covering for the Acheropita icon. The next pope, Honorius III, executed a major restoration of the chapel.