Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr. -

Protecting Log Cabins from Decay

PROTECTING LOG CABINS FROM DECAY USDA Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory General Technical Report FPL-11 1977 U. S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory Madison, Wis. ABSTRACT This report answers the questions most often asked of the Forest Service on the pro- tection of log cabins from decay, and on prac- tices for the exterior finishing and mainte- nance of existing cabins. Causes of stain and decay are discussed, as are some basic techniques for building a cabin that will minimize decay. Selection and handling of logs, their preservative treatment, construction details, descriptions of preserv- ative types, and a complementary bibliography are also included. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.. ................... 1 CAUSES AND CONTROL OF DECAY . 1 Fungal and Insect Damage ........ 1 Preservative Treatments .......... 2 Selection of Preservatives ..... 2 Methods of Application ....... 2 Treatment of Cut Surfaces .... 2 BUILDING TO PREVENT DECAY ..... 3 Selection and Handling of Logs ... 3 Type of Wood ................ 3 Log Preparation .............. 3 Preservative Treating of Logs . 3 Construction Details .............. 4 Foundation ................... 4 Walls ........................ 5 Roof ......................... 5 FINISHING DETAILS ................. 6 Interior .......................... 6 Exterior.. ........................ 6 RESTORING AND MAINTAINING EXISTING CABINS ............... 7 BIBLIOGRAPHY: OTHER HELPFUL PUBLICATIONS .................. 7 APPENDIX: PRESERVATIVE SOLUTIONS.. ................... 8 -

Material for Educators

Material for Educators Lincoln Log Cabin State historic Site 402 South Lincoln Highway Road Lerna, IL 62440 217-345-1845 [email protected] www.lincolnlogcabin.org 2 Table of Contents Introduction To the educators……………………………………………………..…………...……3 Pre-visit Lessons Glossary of Terms and Vocabulary Exercise……………………………………...….6 Lesson 1: Politics and Westward Expansion in the 1840s………………………..…..9 Lesson 2: Settlers’ Homes and Materials Needed for Building……………………..17 Lesson 3: The Lifestyles of the Lincolns and Sargents……………………………...22 Lesson 4: The Life of a Child in the 1840s………………………………………….28 On-Site Activities Visitor’s Center Scavenger Hunt…………………………………………………….34 Visitor’s Center Scavenger Hunt Answers…………………………………………..35 Lincoln Farm Scavenger Hunt……………………………………………………….36 Lincoln Farm Scavenger Hunt Answers……………………………………………..37 Sargent Farm Scavenger Hunt……………………………………………………….39 Sargent Farm Scavenger Hunt Answers……………………………………….…….40 Post-visit Activities “How Big Was That?”……………………………………………………………….43 Crossword Puzzle………………………………………………………………...….44 Crossword Puzzle Answers………………………………………………………….45 Resource guide……………………………………………………………………...46 3 Introduction To the Educators: Lincoln Log Cabin’s educational material was produced by the staff of the Lincoln Log Cabin State Historic Site for the purpose of providing supporting materials which will enhance the students knowledge prior to and after visiting Lincoln Log Cabin. The packet contains two main divisions: Pre-visit and Post-visit activities. Within these divisions, there -

Mushroom Inoculation Instructions

Totem Method: Smaller sections of logs are stacked upright Mushroom Inoculation with sawdust spawn sandwiched between the sections of log. Instructions Large-diameter wood becomes easy to use and attractive to display. The preferred method for Oyster Mushrooms and Most of our mushroom varieties grow on hardwood logs. Lion’s Mane. No special tools are needed. Although almost any hardwood will produce some mushrooms, productivity is influenced by the type of wood 1. Cut three sections of log for each totem: one piece only 1-3" used. The harder hardwoods such as Oak and Maple are long, and two sections 12-18" long. preferred though some softer hardwoods such as Poplar work, 2. Bring your setup to your planned incubation place and particularly with Oyster mushrooms. create totems on site. The best time to cut logs is in early spring before trees have 3. Open a contractor-size black plastic bag, sprinkle a layer of budded out. Only living, disease-free wood should be cut for sawdust spawn about 1" deep in the bottom of the bag, and mushroom logs. stand one of the 12-18" logs upright on top of the spawn. Make another layer of sawdust spawn on top of it, and place the The best time to inoculate logs is in spring, within one to two second 12-18" log on top of that. Create a third layer of weeks after the logs have been cut. This allows the cells in the sawdust spawn on top of the second log and then cap the tree to die but is not long enough for the log to dry out or for totem with the 1-3" piece. -

Dovetails and Broadaxes: Hands-On Log Cabin Preservation

Dovetails and Broadaxes: Hands-On Log Cabin Preservation Appendix E—Log Building Origins and Styles Plan and Form As they moved westward, European-American settlers suc- cessfully adapted log construction techniques to regional materials, climates, and terrains (figures E1 and E2). The floor plan and shape of log buildings constructed in the 1700s and early 1800s sometimes can provide clues to the eth- nic origin or route of migration of the original inhabitant or builder. Because the settlers often borrowed and copied tech- niques used successfully by their neighbors, don’t infer too much about the ethnic origins of a cabin’s builders from the way they constructed the cabin. Figure E2—The builder of this cabin at the mouth of Big Timber Creek Canyon on the Big Timber Ranger District in Montana (Gallatin National Forest, Northern Region) used a stone foundation with massive, battered stone corners and porch piers, and moderate diameter, round, softwood log walls. The cabin has a steep cedar shingled roof and a rock chimney for a wood stove near the center of the building. The entry is on the gable end under a gabled porch. It was sold and removed from the site in the early 1980s. The basic unit of each of these types is the one-room enclo- sure formed by four log walls joined at their corners, called a single pen or crib (figure E3). People sometimes divided the single pen by interior partitions or enlarged them by add- ing another log pen. The typically mid-Atlantic “continental” Figure E1—The two-story Gladie pioneer cabin, built around 1900, was Appendix E—Log Building Origins and Styles restored as part of the Gladie Visitor Center pioneer homestead interpretive site in Kentucky (Daniel Boone National Forest, Southern Region). -

Section 4 Assembling Your Stockade Log System

Section 4 Assembling Your Stockade Log System 4.1 Install Base Course to Foundation (Details L-1-RR & RF) ..... 4-4 Base Course to Subfloor .................................................... 4-4 4.2 Window & Door Bucks (Details L-40 & L-41) ....................... 4-7 Installing Door Bucks ........................................................ 4-8 4.3 Install Wall Courses ................................................................. 4-9 Keep Walls and Corners Plumb ......................................... 4-9 Installing Window Bucks ................................................ 4-10 Stacking Identical Logs ................................................... 4-10 4.4 Second Floor Girder Installation ............................................ 4-11 4.5 Second Floor Beams .............................................................. 4-12 4.6 Temporary Second Floor Decking ......................................... 4-12 4.7 Log Gable Ends ...................................................................... 4-13 How to Install Log Gable Ends ....................................... 4-13 Cutting Log Gable Ends (Detail L-30) ............................ 4-13 Installing Log Siding over Non-Heated Areas 4.8 Installing Doors and Windows (Details L-40; L-41) ............. 4-14 Preparations ..................................................................... 4-14 Installing the Window or Door ........................................ 4-14 Exterior Doors ................................................................. 4-16 4.9 Electrical -

A Nebraska Log Cabin

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, etc. -- Nebraska Forest Service Nebraska Forest Service 2004 A Nebraska Log Cabin Marvin Liewer Colorado State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebforestpubs Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Liewer, Marvin, "A Nebraska Log Cabin" (2004). Publications, etc. -- Nebraska Forest Service. 14. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebforestpubs/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Forest Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, etc. -- Nebraska Forest Service by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Nebraska Log Cabin by Marvin Liewer [ 2004 ] Preface Nebraska pioneers built their homes with materials that were locally available. The prairie often dictated the use of sod. However, logs were generally used when trees were available. Today, logs are used in construction of country homes, vacation cabins, and hunting lodges despite modern construction materials. Log construction is aesthetically pleasing and energy efficient. In 1994, I began building a log cabin along the Niobrara River near Butte, Nebraska. My goal was to build an attractive, comfortable cabin using local wood products. I used ponderosa pine logs for the walls. Bur oak and green ash lumber was used for window and door trim. Stair and porch railings were constructed from hand-peeled eastern redcedar poles. Redcedar boards were also used for paneling the basement. The purpose of this report is to describe local wood products and specific constructions tech- niques used in my successful log cabin project. -

Quare Post, (Round Systems Corner Four • • Exterior Insulation Finish System (EIFS) System Finish Insulation Exterior •

fax: (715) 378-2697 (715) fax: telephone: (715) 378-2640 (715) telephone: e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: web: www.hlhalflog.com web: Solon Springs, WI 54873 WI Springs, Solon .O. Box 222 Box .O. P 11290 South Mertzig Parkway Mertzig South 11290 Flange provides invisible Diameter Log Cabin 10” 12” 14” 16” fastening Siding Oriented Strand Board Stack 1 Height 6 /2” 8” 10” 12” 14” Expanded polystyrene Natural veneer laminated to smooth hardboard 1 1 1 1 Thickness 1 /2” 3” 3 /2” 4 /2” 5 /2” Half logs lock into one another • SuncoatTM High Polymer Acrylic Stain (four standard colors: Amber Ice, Sandy Creek, Autumn Straw, Auburn Ridge) • Pre-finished 2”x8” log cabin siding • Caulk, screws, chinking and trim • H&L Half-Logs, available in 4 diameter sizes, • Large diameter solid log detailing: trusses, posts, headers, purlins 94” lengths (see diagram) and rafters • Ceiling beams in four sizes: 10, 12, 16 and • Interior H&L Half-Logs 20 inch, 94” lengths • Custom veneer options • Four corner systems (round post, square • Exterior insulation finish system (EIFS) timber, saddle notch, and butt and pass) • Custom pre-finishing services (for wood siding products) • Three veneer choices (smooth knotty pine, • Custom H&L Half-Logs to 20” diameter peeled knotty pine and embossed hardboard) • Chinked style H&L Half-Logs Wisconsin Dells Lodge H&L Half-Log ... for high-value H&L Half-LogTM structures. The large diameter creates • Light Weight dramatic curb appeal – 80% lighter than solid log profiles 12” Smooth Pine with Saddle Notch corners - Sandy Creek of the same size The patented H&L and higher resale – structural design cost savings: Half-Log is an values. -

Program Description PD-1 CAMP TAHQUITZ PROGRAM

Camp Tahquitz Summer 2021 Program Description PD-1 CAMP TAHQUITZ PROGRAM THE ADVENTURE STARTS HERE PROGRAM PLANNING HINTS The highlight of any scout's year is the week he spends at summer camp, and the highlights of a Scoutmaster's year is the time that he spends with his scouts in the cool, clean air of Camp Tahquitz. To make sure this happens you should start with good program planning. Here are a few ideas and hints on how to easily plan an exciting, rewarding, and enjoyable week at Tahquitz. BOY PLANNED Planning the troop's summer camp program can be part of the growth process of Scouting if the Scouts themselves are involved through their Patrol Leader’s Council. The PLC, with guidance from the Scoutmaster, should see that the troop program reflects the individual goals of troop members as well as the collective aims of the. Greater scout involvement in planning will assure greater scout enjoyment in participation. BALANCED Experience has shown that the best program at camp is one that offers each scout a healthy balance between recreation and advancement, free time and structured activity, group events and individual pursuits. We recommend that scouts do not undertake more than three merit badges during their stay at camp and that each scout is allowed enough free time to enjoy his surroundings, pursue his interests, and to build friendships. INDIVIDUALIZED A successful camp program reflects the different ages, ranks, and skill levels of the troop. While it is good for the troop to conduct some activities as a whole, other programs should be geared to the personal needs and goals of the troop members. -

California Fire Standards and Exerior Wood Products

WWPA Technical Services Division Tech Notes 2008-01Rev.10 supercedes 2008-01Rev.9 California fire standards and exterior wood products Solid wood products meet wildfire protection regula- Wildfire Exposure” of the California Building Code tions. On January 1, 2008, California implemented (CBC) and cover exterior wood products such as requirements for building materials, systems and assem- siding, decking and soffits. The full standard is avail- blies used in the exterior design and construction of able online at http://www.fire.ca.gov/fire_ new buildings within designated Fire Hazard Severity prevention/downloads/2007_CBC_Ch7A.pdf. Zones (FHSZ). These regulations and standards, initi- The wood species and products listed in this publica- ated by the California State Fire Marshal’s Office tion have been successfully fire-tested or accepted in (OSFM), created new requirements under Chapter 7A, the OSFM’s WUI Products Handbook as meeting the “Materials and Construction Methods for Exterior CBC Chapter 7A for construction in FHSZ. FLAME SPREAD RATINGS Western lumber species flame-spread ratings tested in accordance with ASTM E84 Class B 26-75, Class C 76-200 Western Larch - 45 Port Orford Cedar - 60 Pacific Silver Fir - 69 Idaho White Pine - 82 Ponderosa Pine - 115 Alaska Yellow Cedar - 50 Incense Cedar - 65 Western Red Cedar - 69 Douglas Fir - 90 Engelmann Spruce - 55 Redwood - 65 West Coast Hemlock - 73 Sugar Pine - 95 Hem-Fir - 60 White Fir - 65 Sitka Spruce - 74 Lodgepole Pine - 98 PRODUCT REQUIREMENTS Decking If not otherwise stated, all approved products must Includes decking surfaces, stair treads, risers and landing meet these requirements and be installed as defined. -

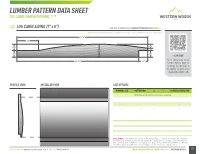

Lumber Pattern Data Sheet Log Cabin Lumber Patterns | V1.0

LUMBER PATTERN DATA SHEET LOG CABIN LUMBER PATTERNS | V1.0 LUMBER PROFILE LOG CABIN SIDING (1” x 8”) FIND THIS PATTERN IN OUR LUMBER PATTERN BOOK ON PAGE 18 » NOTE: Dimensioned pattern drawings are drawn to scale and presented at 100% unless otherwise indicated. 7-3/16” 1-3/16” 7/32” 11/32” 1/8” 23/32” 3/8” 3/8” SCAN HERE Get a digital copy of our 6-11/16” 1/2” Lumber Pattern Book by PATTERN scanning the QR Code or by visiting our website at: 1X8 LOG CABIN SIDING westernwoodsinc.com PROFILE VIEW INSTALLED VIEW SIZE OPTIONS NOMINAL SIZE PATTERN NO. A B CONVERSION FACTOR -- SEE DOCUMENTED SIZE DATA ABOVE -- - - - - - - - - - - 1X8 LOG CABIN SIDING - - - - - PATTERN DISCLAIMER: The dimensions of the delivered product is subject to change due moisture variations experienced by the product during the drying process, storage, or transportation. Site environmental conditions also apply. See page 36 for additional information. Milling variations apply. Consult your local building code for tolerances and specifics. VISIT US ONLINE www.westernwoodsinc.com | CALL US (800) 824-4100 LUMBER PATTERN PRODUCT DATA SHEET v1.0 | WESTERN WOODS 01 LUMBER PATTERN DATA SHEET LOG CABIN LUMBER PATTERNS | V1.0 ALIGNMENTS DESCRIPTION FIND THIS PATTERN IN OUR LUMBER PATTERN BOOK STARTING ON PAGE 18 Horizontal Log Cabin Patterns are 1 1/2” thick at the thickest point. These patterns are ideally suited to informal building in a rustic settings. Vertical Log Cabin may be milled from appearance grades (‘Commons’) or dimension grades (2x material). Allow for a 1/2” overlap (rabbet, C), including an approximate 1/8” gap (B).