Protecting Log Homes from Decay and Insects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ri Wkh% Lrorjlfdo (Iihfwv Ri 6Hohfwhg &Rqvwlwxhqwv

Guidelines for Interpretation of the Biological Effects of Selected Constituents in Biota, Water, and Sediment November 1998 NIATIONAL RRIGATION WQATER UALITY P ROGRAM INFORMATION REPORT No. 3 United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Fish and Wildlife Service Geological Survey Bureau of Indian Affairs 8QLWHG6WDWHV'HSDUWPHQWRI WKH,QWHULRU 1DWLRQDO,UULJDWLRQ:DWHU 4XDOLW\3URJUDP LQIRUPDWLRQUHSRUWQR *XLGHOLQHVIRU,QWHUSUHWDWLRQ RIWKH%LRORJLFDO(IIHFWVRI 6HOHFWHG&RQVWLWXHQWVLQ %LRWD:DWHUDQG6HGLPHQW 3DUWLFLSDWLQJ$JHQFLHV %XUHDXRI5HFODPDWLRQ 86)LVKDQG:LOGOLIH6HUYLFH 86*HRORJLFDO6XUYH\ %XUHDXRI,QGLDQ$IIDLUV 1RYHPEHU 81,7('67$7(6'(3$570(172)7+(,17(5,25 %58&(%$%%,776HFUHWDU\ $Q\XVHRIILUPWUDGHRUEUDQGQDPHVLQWKLVUHSRUWLVIRU LGHQWLILFDWLRQSXUSRVHVRQO\DQGGRHVQRWFRQVWLWXWHHQGRUVHPHQW E\WKH1DWLRQDO,UULJDWLRQ:DWHU4XDOLW\3URJUDP 7RUHTXHVWFRSLHVRIWKLVUHSRUWRUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQFRQWDFW 0DQDJHU1,:43 ' %XUHDXRI5HFODPDWLRQ 32%R[ 'HQYHU&2 2UYLVLWWKH1,:43ZHEVLWHDW KWWSZZZXVEUJRYQLZTS Introduction The guidelines, criteria, and other information in The Limitations of This Volume this volume were originally compiled for use by personnel conducting studies for the It is important to note five limitations on the Department of the Interior's National Irrigation material presented here: Water Quality Program (NIWQP). The purpose of these studies is to identify and address (1) Out of the hundreds of substances known irrigation-induced water quality and to affect wetlands and water bodies, this contamination problems associated with any of volume focuses on only nine constituents or the Department's water projects in the Western properties commonly identified during States. When NIWQP scientists submit NIWQP studies in the Western United samples of water, soil, sediment, eggs, or animal States—salinity, DDT, and the trace tissue for chemical analysis, they face a elements arsenic, boron, copper, mercury, challenge in determining the sig-nificance of the molybdenum, selenium, and zinc. -

Carpenter Ants and Control in Homes Page 1 of 6

Carpenter Ants and Control in Homes Page 1 of 6 Carpenter Ants and Control in Homes Fact Sheet No. 31 Revised May 2000 Dr. Jay B Karren, Extension Entomologist Alan H. Roe, Insect Diagnostician Introduction Carpenter ants are members of the insect order Hymenoptera, which includes bees, wasps, sawflies, and other ants. Carpenter ants can be occasional pests in the home and are noted particularly for the damage they can cause when nesting in wood. In Utah they are more of a nuisance rather than a major structural pest. Carpenter ants, along with a number of other ant species, utilize cavities in wood, particularly stumps and logs in decayed condition, as nesting sites. They are most abundant in forests and can be easily found under loose bark of dead trees, stumps, or fallen logs. Homeowners may bring them into their homes when they transport infested logs from forests to use as firewood. Description Carpenter ants include species that are among the largest ants found in the United States. They are social insects with a complex and well-defined caste system. The worker ants are sterile females and may occur in different sizes (majors and minors). Members of the reproductive caste (fertile males and females) are usually winged prior to mating. All ants develop from eggs deposited by a fertilized female (queen). The eggs hatch into grub-like larvae (immatures) which are fed and cared for by the workers. When fully grown, the larvae spin a cocoon and enter the pupal stage. The pupal stage is a period of transformation from the larva to adult. -

Opinion & Information on Boric Acid

Opinion & Information on Boric Acid By Michael R. Cartwright, Sr. (Michael R. Cartwright, Sr. is a third generation licensed professional in the fields of structural pest control and building construction and is also licensed in agriculture pest control. His qualifications are too extensive to print but are available on request from The Reporter.) Over the past years I have seen, in many homes and restaurants, boric acid covering everything. Carpets, floors, toys and furniture, in kitchen cabinets, on counter tops and tables, in refrigerators, clothing, etc. Why? Because environmentalists, helped by an uninformed news media, tell them to. Why don't the news media also explain the possible dangers of applying something not normally found in the home environment, that you or your animals will come in direct contact with? I'm writing this article even though a California environmentalist group advised me not to say anything against boric acid and that I would pay dearly for only trying to mislead the public. My company uses a lot of boric acid, but not as described above. Under an OSHA Hazard Communication Standard, based on animal chronic toxicity studies of inorganic borate chemicals, boric acid and/or borates are Hazardous Materials. California has identified boric acid as a hazardous waste. The above information is taken from Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) 25-80-2320 (Section 2 and 13) supplied by U.S. Borax Inc. (the major supplier of borax to many industries). The National Academy of Sciences reports that children may be uniquely sensitive to chemicals and pesticide residues because of their rapid tissue growth and development. -

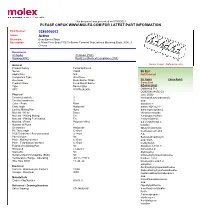

PLEASE CHECK for LATEST PART INFORMATION 0386006603 Active

This document was generated on 07/30/2021 PLEASE CHECK WWW.MOLEX.COM FOR LATEST PART INFORMATION Part Number: 0386006603 Status: Active Overview: Beau Barrier Strips Description: 6.35mm Pitch Beau PCB Tri-Barrier Terminal Strip, without Mounting Ends, 300V, 3 Circuits Documents: 3D Model 3D Model (PDF) Drawing (PDF) RoHS Certificate of Compliance (PDF) General Series image - Reference only Product Family Terminal Blocks Series 38600 EU ELV Application N/A Not Relevant Component Type One Piece Overview Beau Barrier Strips EU RoHS China RoHS Product Name Fixed Mount Barrier Compliant Type Barrier Strip REACH SVHC UPC 800756242606 Contained Per - D(2020)4578-DC (25 Physical June 2020) Circuits (Loaded) 3 henicosafluoroundecanoic Circuits (maximum) 3 acid Color - Resin Black disodium 4- Entry Angle Horizontal amino-3-[[4'-[(2,4- Lock to Mating Part None diaminophenyl)azo] Material - Metal Brass chromium trioxide Material - Plating Mating Tin 1,3-propanesultone Material - Plating Termination Tin 1-vinylimidazole Material - Resin Polyester Alloy 4,4'-methylenedi-o- Number of Rows 1 toluidine Orientation Horizontal dibutyltin dichloride PC Tail Length 5.10mm methoxyacetic acid PCB Thickness - Recommended 3.18mm 1,2- Panel Mount No Benzenedicarboxylic Pitch - Mating Interface 6.35mm acid, bis(3- Pitch - Termination Interface 6.35mm methylbutyl) Polarized to Mating Part No disodium 3,3'-[[1,1'- Shrouded Tri-Barrier biphenyl]-4,4'- Stackable No diylbis(azo) Surface Mount Compatible (SMC) No octamethylcyclotetrasiloxane Temperature Range - Operating -

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania By Thomas M. Brandon Research Assistants: Jonathan P. Brandon and Mario Perona FOLK ARCHITECTURE The term ‘folk architecture’ is often used to draw a distinction between popular or landmark architecture and is nearly synonymous with the terms ‘vernacular architecture’ and ‘traditional architecture.’ Therefore, folk architecture includes those dwellings, places of worship, barns, and other structures that are designed and built without the assistance of formally schooled and professionally trained architects. Folk architecture differs from popular architecture in several ways. For example, folk architecture tends to be utilitarian and conservative, reflecting the specific needs, economics, customs, and beliefs of a particular community. (Source: Oklahoma History Society’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Website. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/F/FO002.html, Alyson L. Greiner, February, 17, 2011). Note. Much of the data and pictures found in this field guide came from a study on log structures in 18 counties of western and central Pennsylvania. The Historic Value of Folk Log Structures The study of folk log construction, also known as horizontal log construction, is exciting because, unlike most artifacts from the pioneer era, log structures have not been moved from where the pioneers used them. The log structure remains intact within the landscape the pioneer who built it intended. Besides the structure itself, which provides valuable information about the specific people who occupied it, the surrounding historic landscape tells it own story of how the family lived, from location of water sources and family dump to the layout of fields, location with other houses in the neighborhood and artifacts found in the ground still in context with their original use. -

Transfer of Ingested Insecticides Among Cockroaches: Effects of Active Ingredient, Bait Formulation, and Assay Procedures

HOUSEHOLD AND STRUCTURAL INSECTS Transfer of Ingested Insecticides Among Cockroaches: Effects of Active Ingredient, Bait Formulation, and Assay Procedures 1 2 1, 3 GRZEGORZ BUCZKOWSKI, ROBERT J. KOPANIC, JR., AND COBY SCHAL J. Econ. Entomol. 94(5): 1229Ð1236(2001) ABSTRACT Foraging cockroaches ingest insecticide baits, translocate them, and can cause mor- tality in untreated cockroaches that contact the foragers or ingest their excretions. Translocation of eight ingested baits by adult male Blattella germanica (L.) was examined in relation to the type of the active ingredient, formulation, and foraging area. Ingested boric acid, chlorpyrifos, Þpronil, and hydramethylnon that were excreted by adults in small dishes killed 100% of Þrst instars within 10 d and Ͼ50% of second instars within 14 d. Residues from these ingested baits were also highly effective on nymphs in larger arenas and killed 16Ð100% of the adults. However, when the baits and dead cockroaches were removed from the large arenas and replaced with new cockroaches, only residues of the slow-acting hydramethylnon killed most of the nymphs and adults, whereas residues of fast acting insecticides (chlorpyrifos and Þpronil) killed fewer nymphs and adults. Excretions from cockroaches that ingested abamectin baits failed to cause signiÞcant mortality in cockroaches that contacted the residues. These results suggest that hydramethylnon is highly effective in these assays because cockroaches that feed on the bait have ample time to return to their shelter and defecate insecticide-laden feces. The relatively high concentration of hydramethylnon in the bait (2.15%) and its apparent stability in the digestive tract and feces probably contribute to the efÞcacy of hydra- methylnon. -

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr. -

Chronology of Pesticides Used on National Park Service Collections

Conserve O Gram June 2001 Number 2/16 Chronology Of Pesticides Used On National Park Service Collections The history of National Park Service pesticide use publication). Synonyms and trade names were policy for museum collection objects is obtained from the Merck Index, notes from the documented in various publications including IPM Coordinator, and two Internet sites Field Manual for Museums (Burns), Manual for (<http://chemfinder.com> and <http:// Museums (Lewis), versions of the Museum www.cdpr.ca.gov/cgi-bin/epa>). Handbook, Part I, and two versions of the Integrated Pest Management Information Manual. Not all of the chemicals listed in the Other non-policy sources include Coleman's accompanying charts were marketed as pesticides. Manual for Small Museums, object treatment Some are fungicides and microbiocides. One, reports and notes from NPS staff, and notes from Lexol, is a leather preservative and consolidant. the Office of the Integrated Pest Management All of these are included here because records (IPM) Coordinator. indicate they were applied to objects as pesticides. The two accompanying charts list the types of The potential for pesticide residue remaining on pesticides that may have been used on National collection objects is very high. Objects with such Park Service collections along with some common residues pose a health risk to curatorial staff and synonyms and trade names. to the public who come into physical contact with them, unless proper precautions are taken. Dates shown in blue on the chart represent Additional information on health and safety issues published recommendations for the use of and protective measures can be found in the pesticides. -

Protecting Log Cabins from Decay

PROTECTING LOG CABINS FROM DECAY USDA Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory General Technical Report FPL-11 1977 U. S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory Madison, Wis. ABSTRACT This report answers the questions most often asked of the Forest Service on the pro- tection of log cabins from decay, and on prac- tices for the exterior finishing and mainte- nance of existing cabins. Causes of stain and decay are discussed, as are some basic techniques for building a cabin that will minimize decay. Selection and handling of logs, their preservative treatment, construction details, descriptions of preserv- ative types, and a complementary bibliography are also included. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.. ................... 1 CAUSES AND CONTROL OF DECAY . 1 Fungal and Insect Damage ........ 1 Preservative Treatments .......... 2 Selection of Preservatives ..... 2 Methods of Application ....... 2 Treatment of Cut Surfaces .... 2 BUILDING TO PREVENT DECAY ..... 3 Selection and Handling of Logs ... 3 Type of Wood ................ 3 Log Preparation .............. 3 Preservative Treating of Logs . 3 Construction Details .............. 4 Foundation ................... 4 Walls ........................ 5 Roof ......................... 5 FINISHING DETAILS ................. 6 Interior .......................... 6 Exterior.. ........................ 6 RESTORING AND MAINTAINING EXISTING CABINS ............... 7 BIBLIOGRAPHY: OTHER HELPFUL PUBLICATIONS .................. 7 APPENDIX: PRESERVATIVE SOLUTIONS.. ................... 8 -

Material for Educators

Material for Educators Lincoln Log Cabin State historic Site 402 South Lincoln Highway Road Lerna, IL 62440 217-345-1845 [email protected] www.lincolnlogcabin.org 2 Table of Contents Introduction To the educators……………………………………………………..…………...……3 Pre-visit Lessons Glossary of Terms and Vocabulary Exercise……………………………………...….6 Lesson 1: Politics and Westward Expansion in the 1840s………………………..…..9 Lesson 2: Settlers’ Homes and Materials Needed for Building……………………..17 Lesson 3: The Lifestyles of the Lincolns and Sargents……………………………...22 Lesson 4: The Life of a Child in the 1840s………………………………………….28 On-Site Activities Visitor’s Center Scavenger Hunt…………………………………………………….34 Visitor’s Center Scavenger Hunt Answers…………………………………………..35 Lincoln Farm Scavenger Hunt……………………………………………………….36 Lincoln Farm Scavenger Hunt Answers……………………………………………..37 Sargent Farm Scavenger Hunt……………………………………………………….39 Sargent Farm Scavenger Hunt Answers……………………………………….…….40 Post-visit Activities “How Big Was That?”……………………………………………………………….43 Crossword Puzzle………………………………………………………………...….44 Crossword Puzzle Answers………………………………………………………….45 Resource guide……………………………………………………………………...46 3 Introduction To the Educators: Lincoln Log Cabin’s educational material was produced by the staff of the Lincoln Log Cabin State Historic Site for the purpose of providing supporting materials which will enhance the students knowledge prior to and after visiting Lincoln Log Cabin. The packet contains two main divisions: Pre-visit and Post-visit activities. Within these divisions, there -

Towards the Efficient Utilization of Geothermal Resources

313 14th New Zealand Geothermal Workshop 1992 TOWARDS THE EFFICIENT UTILIZATION OF GEOTHERMAL RESOURCES R. T. Harper and A. Thain Consultant, Tasman Pulp & Paper Ltd. Manager, Wairakei Geothermal Area, Electricorp - Separated geothermal water from production wells at Wairakei, Ohaaki, Kawerau, Ngawha and other less developed fields in New Zealand, contains potentially valuable chemical constituents. In particular, the extraction of precipitated amorphous silica is discussed in terms of its strategic and beneficial value to expanded energy generation in geothermal development, removal of environmentally sensitive constituents and as a marketable commodity in its own right. The prospect of recovering other minerals thereby the full potential of geothermal resources is considered. Expectations regarding high temperature reinjection could be reviewed in consideration of alternative opportunities which have been advanced in recent years. 1.0 INTRODUCTION proceeding with high temperature reinjection of part of the total separated water flow from Wairakei in an The opportunities to better utilize New Zealand's attempt to reduce the impact of geothermal water flow geothermal resources, which contribute significantly to to the Waikato river. Implementation of a reinjection the nation's wealth are addressed in this paper. The scheme at Wairakei or elsewhere, pre-empts to a degree, developments discussed here, represent a potential the options of recovering minerals and extracting further benefit to geothermal resource owners and operators, energy. Reinjection also involves a considerable capital the community and end users of minerals which are investment. The technologies believed important to the identified as being of commercial value. To date, processing of large water streams have advanced chemical processing of geothermal water has not significantly over recent years and have prompted received much attention and engineering solutions have reconsideration of the expectations of reinjection a been provided to treat separated water.