Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Log Buildings

INFORMATION Know your house LOG BUILDINGS Log building in Heidalen. Photograph: M. Boro © Riksantikvaren The Directorate for Cultural HISTORY Heritage is the adviser to Log construction was the main construction Log construction sets great demands on the the Ministry of Climate method for houses in Norway from the Middle carpenter. In the Middle Ages, log construction and Environment on the development of the Ages until the 1900s. Almost every type of build- developed into a highly advanced technique. national cultural heritage ing was constructed using logs, from churches After the 1700s it became common to panel log policy. The Directorate for and houses to cow byres, hay barns and other buildings in the towns and in the coastal districts, Cultural Heritage is also agricultural buildings. The technique was used and eventually in the flatland communities. This responsible for ensuring the implementation of the both in towns and in the country. In inland val- meant that the requirements for log walls were no national cultural heritage leys you will find beautiful preserved log build- longer as stringent. policy and in this context ings with the log walls clearly visible. is responsible for the work of the county councils The design of log buildings has changed over and the Sami Parliament In rural communities in flatland areas of Nor- time. The design of the log heads and the cor- with cultural heritage, way, along the coast and in our “wooden towns”, ners (tenons) are important when establishing cultural environments and the majority of old wooden buildings are the date of a building. -

Re-Creating Indigenous Architectural Knowledge in Arctic Canada and Norawy

Protection of cultural heritage 9 (2020) 10.35784/odk.2085 RE-CREATING INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURAL KNOWLEDGE IN ARCTIC CANADA AND NORAWY MACKIN Nancy 1 1 dr Nancy Mackin, University of British Columbia and University of Victoria, Canada https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5427-3202 ABSTRACT: Long resident peoples including Gwich’in, Inuvialuit, Copper Inuit, and Sami, Coast Salish and others have learned over countless generations of observation and experimentation to construct place-specific, biomimetic architecture. To learn more about the heritage value of long-resident peoples’ architecture, and to discover how their architecture can selectively inform adaptable architecture of the future. we engaged Inuit and First Nations knowledge-holders and young people in re-creating tradition-based shelters and housing. During the reconstructions, children and Elders alike expressed their enthusiasm and pride in the inventiveness and usefulness of their ancestral architectural wisdom. Several of the structures created during this research are still standing years later and continue to serve as emergency shelters for food harvesters. During extreme weather, the shelters contribute to a potentially widespread network of food harvester dwellings that would facilitate revitalization of traditional foodways. The re-creations indicate that building materials, forms, assembly technologies, and other considerations from the architecture of Indigenous peoples provide a valuable heritage resource for architects of the future. KEY WORDS: Indigenous, Arctic architecture, Inuit architecture, reconstructions, heritage 58 Nancy Mackin 1. Introduction and research questions Tradition-based shelters have always been part of life in the high Arctic, where sudden storms and extreme cold pose serious risks to food harvesters, scientists, and other people out on the land. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Sustainable Features of Vernacular Architecture: Housing of Eastern Black Sea Region As a Case Study

arts Article Sustainable Features of Vernacular Architecture: Housing of Eastern Black Sea Region as a Case Study Burcu Salgın 1,*, Ömer F. Bayram 1, Atacan Akgün 1 and Kofi Agyekum 2 1 Department of Architecture, Erciyes University, Kayseri 38030, Turkey; [email protected] (Ö.F.B.); [email protected] (A.A.) 2 Department of Building Technology, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi 233, Ghana; agyekum.kofi[email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 22 May 2017; Accepted: 4 August 2017; Published: 17 August 2017 Abstract: The contributions of sustainability to architectural designs are steadily increasing in parallel with developments in technology. Although sustainability seems to be a new concept in today’s architecture, in reality, it is not. This is because, much of sustainable architectural design principles depend on references to vernacular architecture, and there are many examples found in different parts of the world to which architects can refer. When the world seeks for more sustainable buildings, it is acceptable to revisit the past in order to understand sustainable features of vernacular architecture. It is clear that vernacular architecture has a knowledge that matters to be studied and classified from a sustainability point of view. This work aims to demonstrate that vernacular architecture can contribute to improving sustainability in construction. In this sense, the paper evaluates specific vernacular housing in Eastern Black Sea Region in Turkey and their response to nature and ecology. In order to explain this response, field work was carried out and the vernacular architectural accumulation of the region was examined on site. -

Franklin, NH, Log House

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON A LOG HOUSE FRANKLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN DECEMBER 5, 2009 This report summarizes observations made during a brief inspection of a log house standing near Webster Lake in Franklin, New Hampshire, on the afternoon of December 1, 2009. The inspection was carried out at the request of the building’s owner, who has conducted considerable research on the property but was seeking an independent evaluation of the significance of the log house. Present at the meeting were Todd M. Workman, the owner, and Peter Michaud and James Garvin of the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources, the State Historic Preservation Office. The following report represents an initial summary of observations made on December 1, 2009, together with recommendations for further research and evaluation. Summary: The log house was built in that part of Andover, New Hampshire, that became part of the Town (later City) of Franklin when that entity was incorporated in 1828. Apart from a small and much-studied group of sawn-log buildings that survive in the coastal region of New Hampshire and adjacent Maine, this house is currently the only known log dwelling to survive in New Hampshire. As such, the building represents the sole example of a building tradition that was once predominant on the New England frontier. -

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania By Thomas M. Brandon Research Assistants: Jonathan P. Brandon and Mario Perona FOLK ARCHITECTURE The term ‘folk architecture’ is often used to draw a distinction between popular or landmark architecture and is nearly synonymous with the terms ‘vernacular architecture’ and ‘traditional architecture.’ Therefore, folk architecture includes those dwellings, places of worship, barns, and other structures that are designed and built without the assistance of formally schooled and professionally trained architects. Folk architecture differs from popular architecture in several ways. For example, folk architecture tends to be utilitarian and conservative, reflecting the specific needs, economics, customs, and beliefs of a particular community. (Source: Oklahoma History Society’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Website. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/F/FO002.html, Alyson L. Greiner, February, 17, 2011). Note. Much of the data and pictures found in this field guide came from a study on log structures in 18 counties of western and central Pennsylvania. The Historic Value of Folk Log Structures The study of folk log construction, also known as horizontal log construction, is exciting because, unlike most artifacts from the pioneer era, log structures have not been moved from where the pioneers used them. The log structure remains intact within the landscape the pioneer who built it intended. Besides the structure itself, which provides valuable information about the specific people who occupied it, the surrounding historic landscape tells it own story of how the family lived, from location of water sources and family dump to the layout of fields, location with other houses in the neighborhood and artifacts found in the ground still in context with their original use. -

Vernacular Architecture in Michoacán. Constructive Tradition As a Response to the Natural and Cultural Surroundings

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 2, Issue 4 – Pages 313-326 Vernacular Architecture in Michoacán. Constructive Tradition as a Response to the Natural and Cultural Surroundings By Eugenia Maria Azevedo-Salomao Luis Alberto Torres-Garibay† Various regions of Mexico (i.e., Michoacán) have a tradition in vernacular architecture with an important wealth heritage. Constructing in this way has a notable ecological quality that has benefits for its inhabitants and the natural and cultural surroundings. This work addresses the habitability of vernacular architecture in Michoacán, making the claim that the tradition of construction methods is anchored to the collective memory and the memory of the lived space. Therefore, memories express themselves as the truth of the past based in the present. In this way, the artisans of Michoacán gathered experience from past generations and distinguished themselves by the rational use of primary materials. With direct observation, surveys to users and literature based researches, selected examples of Michoacán are analyzed. The focus is on permanencies and transformations of the vernacular architecture of the region through the observation of social habits, uses, forms, construction, natural surrounding context and significance to society. The conclusion is reached by questioning why there is a gradual loss of vernacular heritage in the region. It is observed that a necessity for its permanence is required as well as the benefits of the implementation of new techniques that contribute to the regeneration of heritage buildings is emphasized. With sustainability in mind the incorporation of vernacular materials and construction methods together with contemporary solutions is also addressed. Introduction Vernacular architecture is the result of the process of collective creation in a geographical and cultural space. -

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

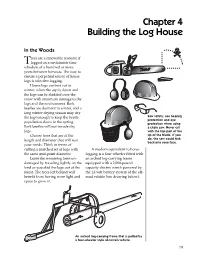

Chapter 4 Building the Log House

Chapter 4 Building the Log House In the Woods rees are a renewable resource if Tlogged on a sustainable time schedule of a hundred or more years between harvests. The way to ensure a perpetual source of house logs is selective logging. House logs are best cut in winter, when the sap is down and the logs can be skidded over the snow with minimum damage to the logs and the environment. Bark beetles are dormant in winter, and a long winter drying season may dry the logs enough to keep the beetle Saw safety: use hearing protection and eye population down in the spring. protection when using Bark beetles will not invade dry a chain saw. Never cut logs. with the top part of the Choose trees that are of the tip of the blade. If you do, the saw could kick length and diameter that will suit back into your face. your needs. Think in terms of cutting a matched set of logs with A modern equivalent to horse- the same mid-point diameter. logging is a four wheeler fitted with Leave the remaining trees un- an arched log-carrying frame damaged by traveling lightly on the equipped with a 2,000-pound land as you skid the logs out of the capacity electric winch powered by forest. The trees left behind will the 12-volt battery system of the off- benefit from having more light and road vehicle (see drawing below). space to grow in. An arched log-carrying frame that is pulled by a four-wheeler style all-terrain vehicle. -

Australian Settler Bush Huts and Indigenous Bark-Strippers: Origins and Influences

Australian settler bush huts and Indigenous bark-strippers: Origins and influences Ray Kerkhove and Cathy Keys [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This article considers the history of the Australian bush hut and its common building material: bark sheeting. It compares this with traditional Aboriginal bark sheeting and cladding, and considers the role of Aboriginal ‘bark strippers’ and Aboriginal builders in establishing salient features of the bush hut. The main focus is the Queensland region up to the 1870s. Introduction For over a century, studies of vernacular architectures in Australia prioritised European high-style colonial vernacular traditions.1 Critical analyses of early Australian colonial vernacular architecture, such as the bush or bark huts of early settlers, were scarce.2 It was assumed Indigenous influences on any European-Australian architecture could not have been consequential.3 This mirrored the global tendency of architectural research, focusing on Western tradi- tions and overlooking Indigenous contributions.4 Over the last two decades, greater appreciation for Australian Indigenous archi- tectures has arisen, especially through Paul Memmott’s ground-breaking Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley: The Indigenous Architecture of Australia (2007). This was recently enhanced by Our Voices: Indigeneity and Architecture (2018) and the Handbook of Indigenous Architecture (2018). The latter volumes located architec- tural expressions of Indigenous identity within broader international movements.5 Despite growing interest in the crossover of Australian Indigenous architectural expertise into early colonial vernacular architectures,6 consideration of intercultural architectural exchange remains limited.7 This article focuses on the early settler Australian bush hut – specifically its widespread use of bark sheets as cladding. -

Protecting Log Cabins from Decay

PROTECTING LOG CABINS FROM DECAY USDA Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory General Technical Report FPL-11 1977 U. S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory Madison, Wis. ABSTRACT This report answers the questions most often asked of the Forest Service on the pro- tection of log cabins from decay, and on prac- tices for the exterior finishing and mainte- nance of existing cabins. Causes of stain and decay are discussed, as are some basic techniques for building a cabin that will minimize decay. Selection and handling of logs, their preservative treatment, construction details, descriptions of preserv- ative types, and a complementary bibliography are also included. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.. ................... 1 CAUSES AND CONTROL OF DECAY . 1 Fungal and Insect Damage ........ 1 Preservative Treatments .......... 2 Selection of Preservatives ..... 2 Methods of Application ....... 2 Treatment of Cut Surfaces .... 2 BUILDING TO PREVENT DECAY ..... 3 Selection and Handling of Logs ... 3 Type of Wood ................ 3 Log Preparation .............. 3 Preservative Treating of Logs . 3 Construction Details .............. 4 Foundation ................... 4 Walls ........................ 5 Roof ......................... 5 FINISHING DETAILS ................. 6 Interior .......................... 6 Exterior.. ........................ 6 RESTORING AND MAINTAINING EXISTING CABINS ............... 7 BIBLIOGRAPHY: OTHER HELPFUL PUBLICATIONS .................. 7 APPENDIX: PRESERVATIVE SOLUTIONS.. ................... 8 -

Sustainability Lessons Learnt from Traditional Architecture: a Case Study of the Old City of As-Salt, Jordan

IOSR Journal Of Environmental Science, Toxicology And Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399. Volume 5, Issue 3 (Jul. - Aug. 2013), PP 100-109 www.Iosrjournals.Org Sustainability lessons learnt from traditional architecture: a case study of the old city of As-Salt, Jordan Rana Tawfiq Almatarneh Assistant professor at The School of Architecture and Design Al-Ahliyya Amman University, Amman- Jordan Abstract: Architecture is the art and science of designing which involves the manipulation of space, materials, program and other elements in order to achieve an end which is aesthetic, functional and sustainable. In the past, when the building envelope was the main element man used to protect himself from a harsh climate, he had to depend on passive energy which involves the use of natural energy sources for environmental, healthy, and economical reasons in our buildings. Traditional architecture, in Jordan, represents a living witness for the suitability of this architecture to the local environment, which incorporated the essence of sustainable architecture. The current study is aimed at investigating the elements of sustainability within the Jordanian traditional buildings based on the Jordan GBI rating key criteria, including: Energy Efficiency, indoor Environmental Quality, sustainable Site Planning and Management, material and Resources, water Efficiency, and innovation. Various typologies of six historical cases (i.e., Abu Jaber, Mouasher, Sukkar, Khatib, Toukan, and Qaqish buildings) in the old city of As-Salt were selected for this study, from a more comprehensive analysis. Findings of the study indicate uniqueness of the overall traditional As-Salt's architecture parallel with the current issues on sustainability.