Log Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franklin, NH, Log House

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON A LOG HOUSE FRANKLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN DECEMBER 5, 2009 This report summarizes observations made during a brief inspection of a log house standing near Webster Lake in Franklin, New Hampshire, on the afternoon of December 1, 2009. The inspection was carried out at the request of the building’s owner, who has conducted considerable research on the property but was seeking an independent evaluation of the significance of the log house. Present at the meeting were Todd M. Workman, the owner, and Peter Michaud and James Garvin of the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources, the State Historic Preservation Office. The following report represents an initial summary of observations made on December 1, 2009, together with recommendations for further research and evaluation. Summary: The log house was built in that part of Andover, New Hampshire, that became part of the Town (later City) of Franklin when that entity was incorporated in 1828. Apart from a small and much-studied group of sawn-log buildings that survive in the coastal region of New Hampshire and adjacent Maine, this house is currently the only known log dwelling to survive in New Hampshire. As such, the building represents the sole example of a building tradition that was once predominant on the New England frontier. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr. -

Chapter 4 Building the Log House

Chapter 4 Building the Log House In the Woods rees are a renewable resource if Tlogged on a sustainable time schedule of a hundred or more years between harvests. The way to ensure a perpetual source of house logs is selective logging. House logs are best cut in winter, when the sap is down and the logs can be skidded over the snow with minimum damage to the logs and the environment. Bark beetles are dormant in winter, and a long winter drying season may dry the logs enough to keep the beetle Saw safety: use hearing protection and eye population down in the spring. protection when using Bark beetles will not invade dry a chain saw. Never cut logs. with the top part of the Choose trees that are of the tip of the blade. If you do, the saw could kick length and diameter that will suit back into your face. your needs. Think in terms of cutting a matched set of logs with A modern equivalent to horse- the same mid-point diameter. logging is a four wheeler fitted with Leave the remaining trees un- an arched log-carrying frame damaged by traveling lightly on the equipped with a 2,000-pound land as you skid the logs out of the capacity electric winch powered by forest. The trees left behind will the 12-volt battery system of the off- benefit from having more light and road vehicle (see drawing below). space to grow in. An arched log-carrying frame that is pulled by a four-wheeler style all-terrain vehicle. -

Trees, Between Nature and Culture Naturopano

naturopaNo. 96 / 2001 • ENGLISH Trees, between nature and culture naturopaNo. 96 – 2001 Editorial B. Rugaas ............................................................................3 Chief Editor José-Maria Ballester Director of Culture and Cultural Forests, a natural heritage and Natural Heritage Trees in Europe, past and present V. Demoulin ....................................4 Director of publication Maguelonne Déjeant-Pons Are Europe’s forests in danger? K. Prins ................................................6 Head of the Regional Planning Co-operation for the benefit of European forests and Technical Co-operation MCPFE and Environment for Europe and Assistance Division P. Mayer and C. Wildburger ....................................................................8 Concept and editing Marie-Françoise Glatz Forests full of life WWF ............................................................................10 E-mail: [email protected] The European Diploma and forests F. Bauer ........................................12 Layout An example outside Europe Emmanuel Georges Trees and the law in Brazil P. A. Leme Machado ................................13 Printer Bietlot – Gilly (Belgium) Man and wood Articles may be freely reprinted provided that reference is made to the source and The relationship between the human race and wood F. Calame ..........14 a copy sent to the Centre Naturopa. The Countless things can be made with wood! P. Glatz ................................15 copyright of all illustrations is reserved. The tree, -

Dovetails and Broadaxes: Hands-On Log Cabin Preservation

Dovetails and Broadaxes: Hands-On Log Cabin Preservation Appendix E—Log Building Origins and Styles Plan and Form As they moved westward, European-American settlers suc- cessfully adapted log construction techniques to regional materials, climates, and terrains (figures E1 and E2). The floor plan and shape of log buildings constructed in the 1700s and early 1800s sometimes can provide clues to the eth- nic origin or route of migration of the original inhabitant or builder. Because the settlers often borrowed and copied tech- niques used successfully by their neighbors, don’t infer too much about the ethnic origins of a cabin’s builders from the way they constructed the cabin. Figure E2—The builder of this cabin at the mouth of Big Timber Creek Canyon on the Big Timber Ranger District in Montana (Gallatin National Forest, Northern Region) used a stone foundation with massive, battered stone corners and porch piers, and moderate diameter, round, softwood log walls. The cabin has a steep cedar shingled roof and a rock chimney for a wood stove near the center of the building. The entry is on the gable end under a gabled porch. It was sold and removed from the site in the early 1980s. The basic unit of each of these types is the one-room enclo- sure formed by four log walls joined at their corners, called a single pen or crib (figure E3). People sometimes divided the single pen by interior partitions or enlarged them by add- ing another log pen. The typically mid-Atlantic “continental” Figure E1—The two-story Gladie pioneer cabin, built around 1900, was Appendix E—Log Building Origins and Styles restored as part of the Gladie Visitor Center pioneer homestead interpretive site in Kentucky (Daniel Boone National Forest, Southern Region). -

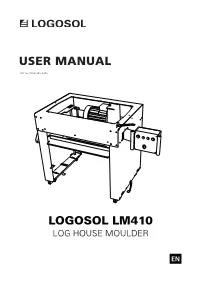

Log House Moulder LM410

USER MANUAL Ref. no. 0458-395-2345 LOGOSOL LM410 LOG HOUSE MOULDER EN THANK YOU FOR CHOOSING A LOGOSOL MACHINE! e are very pleased that you have demonstrated your confidence in us by purchasing this Wmachine, and we will do our utmost to meet your expectations. Logosol has been manufacturing equipment since 1989. In that time we have supplied approximately 50,000 machines to satisfied customers the world over. We care about your safety as well as we want you to achieve the best possible results with this product. We therefore recommend that you take the time to carefully read this user manual from cover to cover in peace and quiet before you begin using the saw. Remember that the machine itself is just part of the value of the product. Much of the value is also to be found in the expertise we pass on to you in the user manuals. It would be a pity if that were not utilised. We hope you get a lot of satisfaction from the use of your new machine. Bengt-Olov Byström Founder and chairman, Logosol in Härnösand, Sweden Read through the user manual carefully and make sure you understand its contents before you use the machine. This user manual contains important safety instructions. WARNING! Incorrect use can result in serious or fatal injuries to the operator or others. LOGOSOL continuously develops its products. For this reason, we must reserve the right to modify the configuration and design of our products. Document: LOGOSOL LM410 User Manual Ref. No. User Manual, English: 0458-395-2345 Text: Mattias Byström, Martin Söderberg, Robert Berglund -

Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site

HOPEWELL FURNACE NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY FINAL Prepared for the National Park Service by Robinson & Associates, Inc. in association with architrave p.c. architects December 1, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS …………………………………………………………….1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……………………………………………………………... 2 NPS ADMINISTRATIVE BACKGROUND ……………………………………………2 National Register Status …………………………………………………………...2 List of Classified Structures Status ………………………………………………..3 Cultural Landscape Report Status …………………………………………………3 Archeological Overview Status …………………………………………………... 3 Status of Resource Management Planning ……………………………………...... 3 INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………………………….. 4 Location and History ……………………………………………………………... 4 Purpose of Study ………………………………………………………………….. 7 Methodology ……………………………………………………………………… 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……………………………………………………………… 10 CHAPTER I: REGIONAL HISTORY PRIOR TO THE ESTABLISHMENT OF HOPEWELL FURNACE …………………………………………………………… 13 Prehistoric Southeastern Pennsylvania …………………………………………… 13 European Settlement and the Departure of the Lenni Lenape ……………………. 14 Berks and Chester Counties ………………………………………………………. 17 Early Pennsylvania Iron Industry ………………………………………………… 19 CHAPTER II: CONSTRUCTION, GROWTH, AND DECLINE OF THE FURNACE, 1771-1883 …………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Establishment by Mark Bird ……………………………………………………… 22 Hopewell Furnace and the American Revolution …………………………………26 Bird’s Debts and the Loss of Hopewell Furnace …………………………………. 28 The Struggle to Become Profitable ………………………………………………..30 -

1815 Log House: Interpretive Manual Timothy Mullin Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Library Presentations, Lectures, Research Guides Libraries Fall 2009 1815 Log House: Interpretive Manual Timothy Mullin Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/lib_pres Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Interior Architecture Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mullin, Timothy, "1815 Log House: Interpretive Manual" (2009). Library Presentations, Lectures, Research Guides. Paper 8. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/lib_pres/8 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Presentations, Lectures, Research Guides by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1815 Log House Interpretive Manual Types of House Museums It is important to understand the different types of house museums and their purposes before we offer information about our own house museum. There are three basic types of house museums: Documentary Representative Decorative Each type has its purpose and distinct interpretive thrust. The Documentary house museum , as its name implies, is based on documentary evidence that is germane to a particular house and its inhabitants . Monticello is a good example of a documentary house museum. As the home of Thomas Jefferson, plans and designs, furniture and account books, letters and drawings provide the information with which that building and its extensive grounds are restored, furnished and interpreted. Based on proprietary documents, Monticello presents colors, objects, surfaces, landscape ...whatever... documented facts about how that particular property looked at a given time which helps create a complete picture of the individual who lived there…Simply put, the documentary house museum documents the life of a specific individual or family. -

Log Construction in Louisiana Historic Context

Log Construction in Louisiana Historic Context Jonathan and Donna Fricker Fricker Historic Preservation Services, LLC March 2012 CONTEXT SUMMARY Log construction, horizontally laid logs attached at the corners via a technique known as notching, occurred historically in various parts of the United States. However, it is most closely identified with what cultural geographers term the Upland South Culture. Indeed, it is an emblem or icon of that group. Cultural geographers vary in their interpretations of virtually every aspect of the Upland South Culture, including its physical boundaries. This document will define the core of Upland South Culture to include West Virginia, western Virginia, the western Carolinas, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Because this core area corresponds to much of Appalachia, sometimes the term Appalachian Uplander is used. (Appalachia is a region in the eastern United States that follows the spine of the Appalachian Mountains from roughly Pennsylvania to northern Alabama.) A significant number of the pioneers who settled the Upland South Culture Region were of Scots-Irish descent (or lived in close proximity with those of Scots-Irish descent and learned their folkways). These were frontiersmen, small landholders – sometimes squatters – in sparse and scattered settlements in a remote hinterland. While the Scots-Irish played a large role in spreading log construction, it was not native to them. Scholars generally agree that they learned the technique in the course of their western expansion, but they disagree as to whether the ultimate origin of log construction in America is via Germany or Scandinavia (Finland and/or Sweden). As migration continued, the Upland South Culture would spread generally in a southwestward fashion to include parts of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas. -

Log Structures : Criteria for Their Description, Evaluation and Management As Cultural Resources

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1982 Log structures : criteria for their description, evaluation and management as cultural resources Margaret L. Glover Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Glover, Margaret L., "Log structures : criteria for their description, evaluation and management as cultural resources" (1982). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3169. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Margaret L. Glover for the Master of Arts in Anthropology presented July 30, 1982. Title: Log Structures: Criteria for their Description, Evaluation and Management as Cultural Resources. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Thomas Newman, Chairman M. Ann Bennett Leslie )rf ildesen This thesis discusses mining cabin sites from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as cultural resources. Special attention is given the concept of "description" in regards to discussion of the resource category, history, and physical attributes of the sites. Evaluation and management suggestions are presented for this particular resource category. To aid in the process of identification of log cabin notching, a typology of notches is developed and presented within the context of the thesis. -

Vernacular Architecture; Definitions; Associations; France; Europe; Africa; Asia

Prepared and edited by Igor Sollogoub, intern at UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre. Préparé et édité par Igor Sollogoub, stagiaire au Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS. © UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre, Mar. 2011 ISBN: 978-2-918086-09-3 ICOMOS - International Council on Monuments and sites / Conseil International des Monuments et des Sites 49-51 rue de la Fédération 75015 Paris FRANCE http://www.international.icomos.org UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Centre / Centre de Documentation UNESCO-ICOMOS : http://www.international.icomos.org/centre_documentation/index.html Cover photographs: Photos de couverture : Mali, Pays Dogon © IRD ; habitat troglodytique en Turquie © IRD ; Dordogne, France © Marie-Ange Mat ; Maison construite dans un banian au Vanuatu ©IRD 1 Index 1. Reference texts / Textes de référence 6 2. Generalities / Généralités 6 3. Africa / Afrique 9 Angola Benin Botswana Burkina Faso Cameroon / Cameroun Ethiopia / Ethiopie Ghana Kenya Madagascar Mali Mauritania / Mauritanie Niger Nigeria Senegal / Sénégal Seychelles South Africa / Afrique du Sud United Republic of Tanzania / Tanzanie Zambia / Zambie Zimbabwe 2 4. Latin America and the Carribean 21 Amérique latine et Caraïbes Argentina / Argentine Barbados / Barbade Belize Bolivia / Bolivie Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela / République bolivarienne du Vénézuela Brazil / Brésil Chile / Chili Colombia / Colombie Costa Rica Cuba Dominican Republic / République dominicaine Ecuador / Equateur El Salvador Guatemala Guyana / Guyane Haiti Jamaica -

Conservation Report for Gellatly House and Barn

CONSERVATION REPORT: THE GELLATLY HOUSE & THE GELLATLY BARN Gellatly Nut Farm Regional Park Westside District Municipality, BC Gellatly Barn and Log House, c. 1905 October 2008 Lorri Dauncey Table of Contents 1. OBJECTIVE 2 2. STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES FOR THE CONSERVATION OF SIGNIFICANT 2 HERITAGE BUILDINGS 3. HISTORICAL CONTEXT 4 4. THE GELLATLY HOUSE 6 4.1 Historical Significance 6 4.2 Cultural Significance 7 4.3 Architectural Significance 7 4.4 Heritage Value and Significance 8 4.5 Alterations and Additions History and Conservation Intervention 9 4.6 Condition Report 14 4.7 Potential Use and Public Access 31 4.8 Conclusion 32 5. THE GELLATLY BARN 32 5.1 Historical Significance 32 5.2 Cultural Significance 33 5.3 Architectural Significance 33 5.4 Heritage Value and Significance 34 5.5 Alterations and Additions History and Conservation Intervention 34 5.6 Condition Report 37 5.7 Potential Use and Public Access 47 5.8 Conclusion 48 6. RECOMMENDATIONS 48 Appendixes: Photographs The Gellatly House Building Plans The Gellatly Barn Building Plans Sources 1 | P a g e Conservation R e p o r t : The Gellatly House & The Gellatly Barn 1. OBJECTIVE The main objective of this report is to provide the necessary historical research, site analysis and building documentation to identify and preserve the heritage value of the Gellatly Barn and the Gellatly House, as part of the Gellatly Nut Farm Regional Park. These vernacular log buildings have significant heritage value as part of the Gellatly Nut Farm site. It is very important to thoroughly document the buildings’ present condition and identify the character defining elements of each building.