Dovetails and Broadaxes: Hands-On Log Cabin Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Log Buildings

INFORMATION Know your house LOG BUILDINGS Log building in Heidalen. Photograph: M. Boro © Riksantikvaren The Directorate for Cultural HISTORY Heritage is the adviser to Log construction was the main construction Log construction sets great demands on the the Ministry of Climate method for houses in Norway from the Middle carpenter. In the Middle Ages, log construction and Environment on the development of the Ages until the 1900s. Almost every type of build- developed into a highly advanced technique. national cultural heritage ing was constructed using logs, from churches After the 1700s it became common to panel log policy. The Directorate for and houses to cow byres, hay barns and other buildings in the towns and in the coastal districts, Cultural Heritage is also agricultural buildings. The technique was used and eventually in the flatland communities. This responsible for ensuring the implementation of the both in towns and in the country. In inland val- meant that the requirements for log walls were no national cultural heritage leys you will find beautiful preserved log build- longer as stringent. policy and in this context ings with the log walls clearly visible. is responsible for the work of the county councils The design of log buildings has changed over and the Sami Parliament In rural communities in flatland areas of Nor- time. The design of the log heads and the cor- with cultural heritage, way, along the coast and in our “wooden towns”, ners (tenons) are important when establishing cultural environments and the majority of old wooden buildings are the date of a building. -

Franklin, NH, Log House

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON A LOG HOUSE FRANKLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN DECEMBER 5, 2009 This report summarizes observations made during a brief inspection of a log house standing near Webster Lake in Franklin, New Hampshire, on the afternoon of December 1, 2009. The inspection was carried out at the request of the building’s owner, who has conducted considerable research on the property but was seeking an independent evaluation of the significance of the log house. Present at the meeting were Todd M. Workman, the owner, and Peter Michaud and James Garvin of the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources, the State Historic Preservation Office. The following report represents an initial summary of observations made on December 1, 2009, together with recommendations for further research and evaluation. Summary: The log house was built in that part of Andover, New Hampshire, that became part of the Town (later City) of Franklin when that entity was incorporated in 1828. Apart from a small and much-studied group of sawn-log buildings that survive in the coastal region of New Hampshire and adjacent Maine, this house is currently the only known log dwelling to survive in New Hampshire. As such, the building represents the sole example of a building tradition that was once predominant on the New England frontier. -

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania By Thomas M. Brandon Research Assistants: Jonathan P. Brandon and Mario Perona FOLK ARCHITECTURE The term ‘folk architecture’ is often used to draw a distinction between popular or landmark architecture and is nearly synonymous with the terms ‘vernacular architecture’ and ‘traditional architecture.’ Therefore, folk architecture includes those dwellings, places of worship, barns, and other structures that are designed and built without the assistance of formally schooled and professionally trained architects. Folk architecture differs from popular architecture in several ways. For example, folk architecture tends to be utilitarian and conservative, reflecting the specific needs, economics, customs, and beliefs of a particular community. (Source: Oklahoma History Society’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Website. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/F/FO002.html, Alyson L. Greiner, February, 17, 2011). Note. Much of the data and pictures found in this field guide came from a study on log structures in 18 counties of western and central Pennsylvania. The Historic Value of Folk Log Structures The study of folk log construction, also known as horizontal log construction, is exciting because, unlike most artifacts from the pioneer era, log structures have not been moved from where the pioneers used them. The log structure remains intact within the landscape the pioneer who built it intended. Besides the structure itself, which provides valuable information about the specific people who occupied it, the surrounding historic landscape tells it own story of how the family lived, from location of water sources and family dump to the layout of fields, location with other houses in the neighborhood and artifacts found in the ground still in context with their original use. -

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr. -

Chapter 4 Building the Log House

Chapter 4 Building the Log House In the Woods rees are a renewable resource if Tlogged on a sustainable time schedule of a hundred or more years between harvests. The way to ensure a perpetual source of house logs is selective logging. House logs are best cut in winter, when the sap is down and the logs can be skidded over the snow with minimum damage to the logs and the environment. Bark beetles are dormant in winter, and a long winter drying season may dry the logs enough to keep the beetle Saw safety: use hearing protection and eye population down in the spring. protection when using Bark beetles will not invade dry a chain saw. Never cut logs. with the top part of the Choose trees that are of the tip of the blade. If you do, the saw could kick length and diameter that will suit back into your face. your needs. Think in terms of cutting a matched set of logs with A modern equivalent to horse- the same mid-point diameter. logging is a four wheeler fitted with Leave the remaining trees un- an arched log-carrying frame damaged by traveling lightly on the equipped with a 2,000-pound land as you skid the logs out of the capacity electric winch powered by forest. The trees left behind will the 12-volt battery system of the off- benefit from having more light and road vehicle (see drawing below). space to grow in. An arched log-carrying frame that is pulled by a four-wheeler style all-terrain vehicle. -

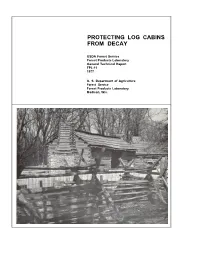

Protecting Log Cabins from Decay

PROTECTING LOG CABINS FROM DECAY USDA Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory General Technical Report FPL-11 1977 U. S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory Madison, Wis. ABSTRACT This report answers the questions most often asked of the Forest Service on the pro- tection of log cabins from decay, and on prac- tices for the exterior finishing and mainte- nance of existing cabins. Causes of stain and decay are discussed, as are some basic techniques for building a cabin that will minimize decay. Selection and handling of logs, their preservative treatment, construction details, descriptions of preserv- ative types, and a complementary bibliography are also included. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.. ................... 1 CAUSES AND CONTROL OF DECAY . 1 Fungal and Insect Damage ........ 1 Preservative Treatments .......... 2 Selection of Preservatives ..... 2 Methods of Application ....... 2 Treatment of Cut Surfaces .... 2 BUILDING TO PREVENT DECAY ..... 3 Selection and Handling of Logs ... 3 Type of Wood ................ 3 Log Preparation .............. 3 Preservative Treating of Logs . 3 Construction Details .............. 4 Foundation ................... 4 Walls ........................ 5 Roof ......................... 5 FINISHING DETAILS ................. 6 Interior .......................... 6 Exterior.. ........................ 6 RESTORING AND MAINTAINING EXISTING CABINS ............... 7 BIBLIOGRAPHY: OTHER HELPFUL PUBLICATIONS .................. 7 APPENDIX: PRESERVATIVE SOLUTIONS.. ................... 8 -

Material for Educators

Material for Educators Lincoln Log Cabin State historic Site 402 South Lincoln Highway Road Lerna, IL 62440 217-345-1845 [email protected] www.lincolnlogcabin.org 2 Table of Contents Introduction To the educators……………………………………………………..…………...……3 Pre-visit Lessons Glossary of Terms and Vocabulary Exercise……………………………………...….6 Lesson 1: Politics and Westward Expansion in the 1840s………………………..…..9 Lesson 2: Settlers’ Homes and Materials Needed for Building……………………..17 Lesson 3: The Lifestyles of the Lincolns and Sargents……………………………...22 Lesson 4: The Life of a Child in the 1840s………………………………………….28 On-Site Activities Visitor’s Center Scavenger Hunt…………………………………………………….34 Visitor’s Center Scavenger Hunt Answers…………………………………………..35 Lincoln Farm Scavenger Hunt……………………………………………………….36 Lincoln Farm Scavenger Hunt Answers……………………………………………..37 Sargent Farm Scavenger Hunt……………………………………………………….39 Sargent Farm Scavenger Hunt Answers……………………………………….…….40 Post-visit Activities “How Big Was That?”……………………………………………………………….43 Crossword Puzzle………………………………………………………………...….44 Crossword Puzzle Answers………………………………………………………….45 Resource guide……………………………………………………………………...46 3 Introduction To the Educators: Lincoln Log Cabin’s educational material was produced by the staff of the Lincoln Log Cabin State Historic Site for the purpose of providing supporting materials which will enhance the students knowledge prior to and after visiting Lincoln Log Cabin. The packet contains two main divisions: Pre-visit and Post-visit activities. Within these divisions, there -

Trees, Between Nature and Culture Naturopano

naturopaNo. 96 / 2001 • ENGLISH Trees, between nature and culture naturopaNo. 96 – 2001 Editorial B. Rugaas ............................................................................3 Chief Editor José-Maria Ballester Director of Culture and Cultural Forests, a natural heritage and Natural Heritage Trees in Europe, past and present V. Demoulin ....................................4 Director of publication Maguelonne Déjeant-Pons Are Europe’s forests in danger? K. Prins ................................................6 Head of the Regional Planning Co-operation for the benefit of European forests and Technical Co-operation MCPFE and Environment for Europe and Assistance Division P. Mayer and C. Wildburger ....................................................................8 Concept and editing Marie-Françoise Glatz Forests full of life WWF ............................................................................10 E-mail: [email protected] The European Diploma and forests F. Bauer ........................................12 Layout An example outside Europe Emmanuel Georges Trees and the law in Brazil P. A. Leme Machado ................................13 Printer Bietlot – Gilly (Belgium) Man and wood Articles may be freely reprinted provided that reference is made to the source and The relationship between the human race and wood F. Calame ..........14 a copy sent to the Centre Naturopa. The Countless things can be made with wood! P. Glatz ................................15 copyright of all illustrations is reserved. The tree, -

Mushroom Inoculation Instructions

Totem Method: Smaller sections of logs are stacked upright Mushroom Inoculation with sawdust spawn sandwiched between the sections of log. Instructions Large-diameter wood becomes easy to use and attractive to display. The preferred method for Oyster Mushrooms and Most of our mushroom varieties grow on hardwood logs. Lion’s Mane. No special tools are needed. Although almost any hardwood will produce some mushrooms, productivity is influenced by the type of wood 1. Cut three sections of log for each totem: one piece only 1-3" used. The harder hardwoods such as Oak and Maple are long, and two sections 12-18" long. preferred though some softer hardwoods such as Poplar work, 2. Bring your setup to your planned incubation place and particularly with Oyster mushrooms. create totems on site. The best time to cut logs is in early spring before trees have 3. Open a contractor-size black plastic bag, sprinkle a layer of budded out. Only living, disease-free wood should be cut for sawdust spawn about 1" deep in the bottom of the bag, and mushroom logs. stand one of the 12-18" logs upright on top of the spawn. Make another layer of sawdust spawn on top of it, and place the The best time to inoculate logs is in spring, within one to two second 12-18" log on top of that. Create a third layer of weeks after the logs have been cut. This allows the cells in the sawdust spawn on top of the second log and then cap the tree to die but is not long enough for the log to dry out or for totem with the 1-3" piece. -

Section 4 Assembling Your Stockade Log System

Section 4 Assembling Your Stockade Log System 4.1 Install Base Course to Foundation (Details L-1-RR & RF) ..... 4-4 Base Course to Subfloor .................................................... 4-4 4.2 Window & Door Bucks (Details L-40 & L-41) ....................... 4-7 Installing Door Bucks ........................................................ 4-8 4.3 Install Wall Courses ................................................................. 4-9 Keep Walls and Corners Plumb ......................................... 4-9 Installing Window Bucks ................................................ 4-10 Stacking Identical Logs ................................................... 4-10 4.4 Second Floor Girder Installation ............................................ 4-11 4.5 Second Floor Beams .............................................................. 4-12 4.6 Temporary Second Floor Decking ......................................... 4-12 4.7 Log Gable Ends ...................................................................... 4-13 How to Install Log Gable Ends ....................................... 4-13 Cutting Log Gable Ends (Detail L-30) ............................ 4-13 Installing Log Siding over Non-Heated Areas 4.8 Installing Doors and Windows (Details L-40; L-41) ............. 4-14 Preparations ..................................................................... 4-14 Installing the Window or Door ........................................ 4-14 Exterior Doors ................................................................. 4-16 4.9 Electrical -

A Nebraska Log Cabin

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, etc. -- Nebraska Forest Service Nebraska Forest Service 2004 A Nebraska Log Cabin Marvin Liewer Colorado State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebforestpubs Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Liewer, Marvin, "A Nebraska Log Cabin" (2004). Publications, etc. -- Nebraska Forest Service. 14. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebforestpubs/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Forest Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, etc. -- Nebraska Forest Service by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A Nebraska Log Cabin by Marvin Liewer [ 2004 ] Preface Nebraska pioneers built their homes with materials that were locally available. The prairie often dictated the use of sod. However, logs were generally used when trees were available. Today, logs are used in construction of country homes, vacation cabins, and hunting lodges despite modern construction materials. Log construction is aesthetically pleasing and energy efficient. In 1994, I began building a log cabin along the Niobrara River near Butte, Nebraska. My goal was to build an attractive, comfortable cabin using local wood products. I used ponderosa pine logs for the walls. Bur oak and green ash lumber was used for window and door trim. Stair and porch railings were constructed from hand-peeled eastern redcedar poles. Redcedar boards were also used for paneling the basement. The purpose of this report is to describe local wood products and specific constructions tech- niques used in my successful log cabin project.