Log Construction in Louisiana Historic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Maintaining the Historic Character of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence

United States Forest Department of Service Agriculture Technology & Development Program A Guide to Maintaining 2300–Recreation April 2014 the Historic Character 1423–2815P–MTDC of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence Cover: This photo in September 1923 shows a newly built recreation residence in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains at the Silver Creek tract of the Rainier National Forest, which is now part of the Mt. Baker- Snoqualmie National Forest in the Pacific Northwest Region. A Guide to Maintaining the Historic Character of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence Kathleen Snodgrass Project Leader USDA Forest Service Technology and Development Center Missoula, MT April 2014 USDA Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, Adjudication, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, by fax (202) employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, 690-7442 or email at [email protected]. disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual’s income is Persons with Disabilities derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment Individuals who are deaf, hard of hearing or have speech disabilities and you wish to file either or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases an EEO or program complaint please contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) 877-8339 or (800) 845-6136 (in Spanish). -

Log Buildings

INFORMATION Know your house LOG BUILDINGS Log building in Heidalen. Photograph: M. Boro © Riksantikvaren The Directorate for Cultural HISTORY Heritage is the adviser to Log construction was the main construction Log construction sets great demands on the the Ministry of Climate method for houses in Norway from the Middle carpenter. In the Middle Ages, log construction and Environment on the development of the Ages until the 1900s. Almost every type of build- developed into a highly advanced technique. national cultural heritage ing was constructed using logs, from churches After the 1700s it became common to panel log policy. The Directorate for and houses to cow byres, hay barns and other buildings in the towns and in the coastal districts, Cultural Heritage is also agricultural buildings. The technique was used and eventually in the flatland communities. This responsible for ensuring the implementation of the both in towns and in the country. In inland val- meant that the requirements for log walls were no national cultural heritage leys you will find beautiful preserved log build- longer as stringent. policy and in this context ings with the log walls clearly visible. is responsible for the work of the county councils The design of log buildings has changed over and the Sami Parliament In rural communities in flatland areas of Nor- time. The design of the log heads and the cor- with cultural heritage, way, along the coast and in our “wooden towns”, ners (tenons) are important when establishing cultural environments and the majority of old wooden buildings are the date of a building. -

Franklin, NH, Log House

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON A LOG HOUSE FRANKLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN DECEMBER 5, 2009 This report summarizes observations made during a brief inspection of a log house standing near Webster Lake in Franklin, New Hampshire, on the afternoon of December 1, 2009. The inspection was carried out at the request of the building’s owner, who has conducted considerable research on the property but was seeking an independent evaluation of the significance of the log house. Present at the meeting were Todd M. Workman, the owner, and Peter Michaud and James Garvin of the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources, the State Historic Preservation Office. The following report represents an initial summary of observations made on December 1, 2009, together with recommendations for further research and evaluation. Summary: The log house was built in that part of Andover, New Hampshire, that became part of the Town (later City) of Franklin when that entity was incorporated in 1828. Apart from a small and much-studied group of sawn-log buildings that survive in the coastal region of New Hampshire and adjacent Maine, this house is currently the only known log dwelling to survive in New Hampshire. As such, the building represents the sole example of a building tradition that was once predominant on the New England frontier. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr. -

Chapter 4 Building the Log House

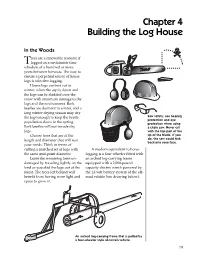

Chapter 4 Building the Log House In the Woods rees are a renewable resource if Tlogged on a sustainable time schedule of a hundred or more years between harvests. The way to ensure a perpetual source of house logs is selective logging. House logs are best cut in winter, when the sap is down and the logs can be skidded over the snow with minimum damage to the logs and the environment. Bark beetles are dormant in winter, and a long winter drying season may dry the logs enough to keep the beetle Saw safety: use hearing protection and eye population down in the spring. protection when using Bark beetles will not invade dry a chain saw. Never cut logs. with the top part of the Choose trees that are of the tip of the blade. If you do, the saw could kick length and diameter that will suit back into your face. your needs. Think in terms of cutting a matched set of logs with A modern equivalent to horse- the same mid-point diameter. logging is a four wheeler fitted with Leave the remaining trees un- an arched log-carrying frame damaged by traveling lightly on the equipped with a 2,000-pound land as you skid the logs out of the capacity electric winch powered by forest. The trees left behind will the 12-volt battery system of the off- benefit from having more light and road vehicle (see drawing below). space to grow in. An arched log-carrying frame that is pulled by a four-wheeler style all-terrain vehicle. -

A Big Success

VALUE ADDED The Little Things Make This Company a Big Success by Bill Tice or Rob Wrightman, president and CEO of True North Log Homes Inc. in Bracebridge, Ont., making the decision to go into the highly competitive log home business was easy. Developing a product that would set him apart from the competition was supposed to have been the hard part. But for Wrightman, achieving that com- petitive edge simply meant going back to basics and solving a long-term problem for the log home industry – gaps that are created when the structure settles and allows air into the home. age log building you will have about 40 rods,” he explains. Wrightman, who has a self-proclaimed interest in tech- “In the past, it would take two days to install all of the rods nology, has four U.S. and Canadian patents in the works with two guys. Now, with the spring action, it takes half a right now, including one for his new “Log Lock Thru-bolt” day or less with one man.” assembly system, which is a spring loaded, self-adjusting Following more than two years of development, Wright- method of joining the logs together. “Two feet from every man started installing the new “Log Lock” system in his corner and between each door and window opening we fac- company’s log homes earlier this year, but there is more to tory drill a hole for a one–piece through bolt to be inserted his log homes than just steel rods, springs and bolts. “It’s also at the time of assembly,” explains Wrightman when provid- the quality of the materials we use, the workmanship, and ing a simplistic description of the technology. -

Alaska Log Building Construction Guide

AlaskaAlaska LogLog BuildingBuilding ConstructionConstruction GuideGuide BuildingBuilding Energy-Efficient,Energy-Efficient, QualityQuality LogLog StructuresStructures inin AlaskaAlaska by Michael Musick illustrated by Russell C. Mitchell for Alaska Housing Finance Corporation Alaska Log Building Construction Guide by Mike Musick additional text by Phil Loudon edited by Sue Mitchell graphics by Russell Mitchell photos by Mike Musick or as noted for Alaska Housing Finance Corporation When we build, let us think that we build forever. Let it not be for present “delight nor for present use alone. Let it be such work as our descendants will thank us for; and let us think, as we lay stone upon stone, that a time is to come when those stones will be held sacred because our hands have touched them, and that people will say, as they look upon the labor and wrought substance of them, “See! This our parents did for us.” —John Ruskin ” ii Acknowledgements he authors would like to thank the many people who made this book Tpossible. Please know that your contribution is appreciated, even if we forgot to mention you here. Phil Loudon contributed a lot of time and text to the retrofit chapter. Sandy Jamieson, noted artist and master log builder, provided thoughtful comments and review. Phil Kaluza, energy specialist for Alaska Housing Finance Corporation (AHFC), contributed the sample energy ratings in Appendix C and other information on AkWarm. And particularly, this book would not have been possible without Bob Brean, director of the Research and Rural Development Division; Lucy Carlo, research and rural development specialist; and Mimi Burbage, energy specialist for AHFC. -

The Vernacular Houses of Harlan County, Kentucky

-ABSTRACT WHAT is the vernacular ? Are some houses vernacular while others are not? Traditional definitions suggest that only those buildings that are indigenous, static and handmade can be considered vernacular. This thesis uses Harlan County, Kentucky as a case study to argue that vernacular architecture includes not only those houses that are handmade, timeless and traditional but also those houses that are industrial and mass-produced. Throughout the 19 th century Harlan County was an isolated, mountainous region where settlers built one and two-room houses from logs, a readily available material. At the turn of the century a massive coal boom began, flooding the county with people and company-built coal camp houses which were built in large quantities as cheaply as possible with milled lumber and hired help. Given traditional conceptions of the vernacular, it would have been appropriate to assume the vernacular tradition of house building ended as camp houses, those houses that were not built directly by the residents with manufactured materials, began to replace the traditional log houses. However, the research presented in this thesis concludes that many elements of form, construction and usage that were first manifest in the handmade log cabins continued to be expressed in the county’s mass-produced camp houses. These camp houses not only manifest an evolution of local building traditions but also established qualities of outside influence which in turn were embraced by the local culture. Harlan County’s houses make the case for a more inclusive conception of vernacular architecture. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 6 I. -

Perspecta+21.Pdf

About Perspecta z r Editors Thanks ro Send editorial correspondence ro: Carol Burns The printing of J. Glynnis Berry, Aaron BetsÞy, Liz Bmns, Perspecta ,{rchitecture is not an isolated or Robert Taylor this journal was made Mary Curtain, Stacy Genuni/1, Bolt Goll¿/, P.O. Box zrzr,Yale University autonomous medium; it is actively possible in part by Bi// Grego, Sìanøk Hariri, Richard Hays, New Haven, Connecticut o65zo engaged by the social, intellectual, and genefous gifts from: Design Peter MacKeitlt, and Llnn Ulhalen. visual culture which is outside the Gønnar Birþert¡ Joseþb Gugliettì Send orders and business discipline and which encompasses it. Burgee uitb Special thanks to correspondence to: Jobn Though grounded in the time and place Joseph Bednar Sandra C enterlnooþ Arch i tects of its making, architecture is capable Cloud and Aluin Eisennan The MIT Press Journals Department Robert Taylor Dauid M. Child¡ of reshaping the z8 Carlecon Srreet cultural matrix from Henry Cobb which it rises. A vital architecture The Norfolk projects were aided by a Cambridge, Massachuset ts c2t 'lYaten is one 42 Cox Graphic Production grant from the Graham Foundarion for J, that resonates with that culture. It is Page Rbineiteck Gwathmey Siegel and Assocìates this resonance, not reference Âdvanced Studies in Fine Art. In the Unired Kingdom, conrinenral to some Hehnzt locus left behind or yet Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Jahn to be found, Copy Editor Kohn Pedersen Fox gives Perspecta 2r was designed during send orders and business which architecrure its power. Rutb Hein Herbert McLaughlin 1984 in New Haven, Connecticut. -

List of House Types

List of house types This is a list of house types. Houses can be built in a • Assam-type House: a house commonly found in large variety of configurations. A basic division is be- the northeastern states of India.[2] tween free-standing or Single-family houses and various types of attached or multi-user dwellings. Both may vary • Barraca: a traditional style of house originated in greatly in scale and amount of accommodation provided. Valencia, Spain. Is a historical farm house from the Although there appear to be many different types, many 12th century BC to the 19th century AD around said of the variations listed below are purely matters of style city. rather than spatial arrangement or scale. Some of the terms listed are only used in some parts of the English- • Barndominium: a type of house that includes liv- speaking world. ing space attached to either a workshop or a barn, typically for horses, or a large vehicle such as a recreational vehicle or a large recreational boat. 1 Detached single-unit housing • Bay-and-gable: a type of house typically found in the older areas of Toronto. Main article: Single-family detached home • Bungalow: any simple, single-storey house without any basement. • A-frame: so-called because of the appearance of • the structure, namely steep roofline. California Bungalow • Addison house: a type of low-cost house with metal • Cape Cod: a popular design that originated in the floors and cavity walls made of concrete blocks, coastal area of New England, especially in eastern mostly built in the United Kingdom and in Ireland Massachusetts. -

Trees, Between Nature and Culture Naturopano

naturopaNo. 96 / 2001 • ENGLISH Trees, between nature and culture naturopaNo. 96 – 2001 Editorial B. Rugaas ............................................................................3 Chief Editor José-Maria Ballester Director of Culture and Cultural Forests, a natural heritage and Natural Heritage Trees in Europe, past and present V. Demoulin ....................................4 Director of publication Maguelonne Déjeant-Pons Are Europe’s forests in danger? K. Prins ................................................6 Head of the Regional Planning Co-operation for the benefit of European forests and Technical Co-operation MCPFE and Environment for Europe and Assistance Division P. Mayer and C. Wildburger ....................................................................8 Concept and editing Marie-Françoise Glatz Forests full of life WWF ............................................................................10 E-mail: [email protected] The European Diploma and forests F. Bauer ........................................12 Layout An example outside Europe Emmanuel Georges Trees and the law in Brazil P. A. Leme Machado ................................13 Printer Bietlot – Gilly (Belgium) Man and wood Articles may be freely reprinted provided that reference is made to the source and The relationship between the human race and wood F. Calame ..........14 a copy sent to the Centre Naturopa. The Countless things can be made with wood! P. Glatz ................................15 copyright of all illustrations is reserved. The tree, -

Etag 012 Log Building Kits

European Organisation for Technical Approvals Europäische Organisation für Technische Zulassungen Organisation Européenne pour l'Agrément Technique TB ETAG 012 Edition June 2002 GUIDELINE FOR EUROPEAN TECHNICAL APPROVAL OF LOG BUILDING KITS EOTA KUNSTLAAN 40 AVENUE DES ARTS, 1040 BRUSSELS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION 1 PRELIMINARIES 6 1.1 Legal basis 6 1.2 Status of ETAG 6 2SCOPE 7 2.1 SCOPE 7 2.2 Use categories/Product families/Kits and Systems 7 2.3 Assumptions 7 3 TERMINOLOGY 9 3.1 Common terminology and abbreviations 9 3.2 Terminology specific to this ETAG 9 SECTION TWO : GUIDANCE FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE FITNESS FOR USE 11 4 REQUIREMENTS 13 4.1 Mechanical resistance and stability (ER 1) 14 4.2 Safety in case of fire (ER 2) 15 4.3 Hygiene, health and environment (ER 3) 15 4.4 Safety in use (ER 4) 16 4.5 Protection against noise (ER 5) 16 4.6 Energy economy and heat retention (ER 6) 17 4.7 Aspects of durability, serviceability and identification 17 5 METHODS OF VERIFICATION 18 5.1 Mechanical resistance and stability 19 5.2 Safety in case of fire 19 5.3 Hygiene, health and environment 20 5.4 Safety in use 22 5.5 Protection against noise 22 5.6 Energy economy and heat retention 22 5.7 Aspects of durability, serviceability and identification 23 6 ASSESSING AND JUDGING THE FITNESS FOR USE 26 6.1 Mechanical resistance and stability 27 6.2 Safety in case of fire 29 6.3 Hygiene, health and environment 29 6.4 Safety in use 30 6.5 Protection against noise 30 6.6 Energy economy and heat retention 30 6.7 Aspects of durability, serviceability and identification 31 7 ASSUMPTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS UNDER WHICH THE FITNESS FOR USE OF THE PRODUCTS IS ASSESSED 33 7.1 Design of works 33 7.2 Packaging, transport and storage 33 7.3 Execution of works 33 ETAG 012 Page 2 7.4 Maintenance 34 SECTION THREE : ATTESTATION AND EVALUATION OF CONFORMITY 35 8 ATTESTATION AND EVALUATION OF CONFORMITY 35 8.1 EC decision 35 8.2 Responsibilities 35 8.3 Documentation 37 8.4 CE marking and information 37 SECTION FOUR :ETA CONTENT 39 9 THE ETA CONTENT 39 9.1 The ETA-content.