If You Build It, They Will Come

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

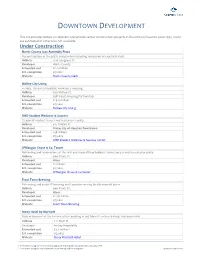

Downtown Development Project List

DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT This list provides details on all public and private sector construction projects in Downtown Houston since 1995. Costs are estimated or otherwise not available. Under Construction Harris County Jury Assembly Plaza Reconstruction of the plaza and pavilion including relocation of electrical vault. Address 1210 Congress St. Developer Harris County Estimated cost $11.3 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Harris County Clerk McKee City Living 4‐story, 120‐unit affordable‐workforce housing. Address 626 McKee St. Developer Gulf Coast Housing Partnership Estimated cost $29.9 million Est. completion 4Q 2021 Website McKee City Living UHD Student Wellness & Success 72,000 SF student fitness and recreation facility. Address 315 N Main St. Developer University of Houston Downtown Estimated cost $38 million Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website UHD Student Wellness & Success Center JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tower Reframing and renovations of the first and second floor lobbies, tunnel access and the exterior plaza. Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website JPMorgan Chase & Co Tower Frost Town Brewing Reframing and 9,100 SF brewing and taproom serving locally inspired beers Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2.58 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Frost Town Brewing Moxy Hotel by Marriott Redevelopment of the historic office building at 412 Main St. into a 13‐story, 119‐room hotel. Address 412 Main St. Developer InnJoy Hospitality Estimated cost $4.4 million P Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website Moxy Marriott Hotel V = Estimated using the Harris County Appriasal Distict public valuation data, January 2019 P = Estimated using the City of Houston's permitting and licensing data Updated 07/01/2021 Harris County Criminal Justice Center Improvement and flood damage mitigation of the basement and first floor. -

New Report ID

Number 21 April 2004 BAKER INSTITUTE REPORT NOTES FROM THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY BAKER INSTITUTE CELEBRATES ITS 10TH ANNIVERSARY Vice President Dick Cheney was man you only encounter a few the keynote speaker at the Baker times in life—what I call a ‘hun- See our special Institute’s 10th anniversary gala, dred-percenter’—a person of which drew nearly 800 guests to ability, judgment, and absolute gala feature with color a black-tie dinner October 17, integrity,” Cheney said in refer- 2003, that raised more than ence to Baker. photos on page 20. $3.2 million for the institute’s “This is a man who was chief programs. Cynthia Allshouse and of staff on day one of the Reagan Rice trustee J. D. Bucky Allshouse years and chief of staff 12 years ing a period of truly momentous co-chaired the anniversary cel- later on the last day of former change,” Cheney added, citing ebration. President Bush’s administra- the fall of the Soviet Union, the Cheney paid tribute to the tion,” Cheney said. “In between, Persian Gulf War, and a crisis in institute’s honorary chair, James he led the treasury department, Panama during Baker’s years at A. Baker, III, and then discussed oversaw two landslide victories in the Department of State. the war on terrorism. presidential politics, and served “There is a certain kind of as the 61st secretary of state dur- continued on page 24 NIGERIAN PRESIDENT REFLECTS ON CHALLENGES FACING HIS NATION President Olusegun Obasanjo of the Republic of Nigeria observed that Africa, as a whole, has been “unstable for too long” during a November 5, 2003, presentation at the Baker Institute. -

30Th Anniversary of the Center for Public History

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 HISTORY MATTERS 30th Anniversary of the Center for Public History Teaching and Collection Training and Research Preservation and Study Dissemination and Promotion CPH Collaboration and Partnerships Innovation Outreach Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 28½ Years Marty Melosi was the Lone for excellence in the fields of African American history and Ranger of public history in our energy/environmental history—and to have generated new region. Thirty years ago he came knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston to the University of Houston to region, broadly defined. establish and build the Center Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public for Public History (CPH). I have Library announced that it would stop publishing the been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. years. Together with many others, CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. we have built a sturdy outpost of We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house history in a region long neglectful the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of its past. of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP “Public history” includes his- became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional his- Joseph A. Pratt torical research and training for tory pouring out of CPH. careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to interesting and fun. -

CITY of HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Melrose Building AGENDA ITEM: C OWNERS: Wang Investments Networks, Inc. HPO FILE NO.: 15L305 APPLICANT: Anna Mod, SWCA DATE ACCEPTED: Mar-02-2015 LOCATION: 1121 Walker Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Mar-26-2015 SITE INFORMATION Tracts 1, 2, 3A & 16, Block 94, SSBB, City of Houston, Harris County, Texas. The site includes a 21- story skyscraper. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark Designation HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY The Melrose Building is a twenty-one story office tower located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. It was designed by prolific Houston architecture firm Lloyd & Morgan in 1952. The building is Houston’s first International Style skyscraper and the first to incorporate cast concrete cantilevered sunshades shielding rows of grouped windows. The asymmetrical building is clad with buff colored brick and has a projecting, concrete sunshade that frames the window walls. The Melrose Building retains a high degree of integrity on the exterior, ground floor lobby and upper floor elevator lobbies. The Melrose Building meets Criteria 1, 4, 5, and 6 for Landmark designation of Section 33-224 of the Houston Historic Preservation Ordinance. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE Location and Site The Melrose Building is located at 1121 Walker Street in downtown Houston. The property includes only the office tower located on the southeastern corner of Block 94. The block is bounded by Walker Street to the south, San Jacinto Street to the east, Rusk Street to the north, and Fannin Street to the west. The surrounding area is an urban commercial neighborhood with surface parking lots, skyscrapers, and multi-story parking garages typical of downtown Houston. -

The Pipeline

HOUSTON CHAPTER—AMERICAN GUILD OF ORGANISTS November 2015-January 2016 THE PIPELINE DEAN’S COLUMN Kathryn Sparks White echnology is changing rapidly and the AGO is working hard to keep up! Here are INSIDE THIS ISSUE T just a few of the recent advancements that benefit our image, our members, and our bottom line: Page 1 New members are being attracted by the Guild’s seven regional online-only (“virtual”) chapters Dean’s Column for organists under 30. Honorary Life Member Convention check in will be expedited: Volunteers will scan the barcode you received when you Officers registered online. We’ve developed a handy Convention app for your mobile device (more info in this issue). Page 2 And, after this season, The Pipeline will be distributed as an electronic newsletter! As they’ve always been, new and archived issues are available on our Chapter website. 2016 Houston Chapter Events The 2015-2016 Chapter Directory is now available on the chapter website. This new edition is based solely on information you provided in ONCARD. I recommend that everyone logs Page 3 onto the ONCARD website (https://www.agohq.org/oncard-login) and reviews his or her Innovation to Convention information. It is easy to log on; they have prompts to help you. In addition, please add your Leadership Award places of employment, positions, and certifications. Thanks to Andrew Bowen for his hard work in preparing the directory and monitoring ONCARD. Insert Sheet Our season began on September 20 with a brilliant and energetic concert by Patrick Scott at 2016 Convention Report St. -

Houstonhouston

RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Texas A&M University July 2001 © 2001, Real Estate Center. All rights reserved. RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Contents 2 Note Population 6 Employment 9 Job Market 10 Major Industries 11 Business Climate 13 Public Facilities 14 Transportation and Infrastructure Issues 16 Urban Growth Patterns Map 1. Growth Areas Education 18 Housing 23 Multifamily 25 Map 2. Multifamily Building Permits 26 Manufactured Housing Seniors Housing 27 Retail Market 29 Map 3. Retail Building Permits 30 Office Market Map 4. Office Building Permits 33 Industrial Market Map 5. Industrial Building Permits 35 Conclusion RealReal EstateEstate MarketMarket OverviewOverview HoustonHouston Jennifer S. Cowley Assistant Research Scientist Aldine Jersey Village US Hwy 59 US Hwy 290 Interstate 45 Sheldon US Hwy 90 Spring Valley Channelview Interstate 10 Piney Point Village Houston Galena Park Bellaire US Hwy 59 Deer Park Loop 610 Pasadena US Hwy 90 Stafford Sugar Land Beltway 8 Brookside Village Area Cities and Towns Counties Land Area of Houston MSA Baytown La Porte Chambers 5,995 square miles Bellaire Missouri City Fort Bend Conroe Pasadena Harris Population Density (2000) Liberty Deer Park Richmond 697 people per square mile Galena Park Rosenberg Montgomery Houston Stafford Waller Humble Sugar Land Katy West University Place ouston, a vibrant metropolitan City Business Journals. The city had a growing rapidly. In 2000, Houston was community, is Texas’ largest population of 44,633 in 1900, growing ranked the most popular U.S. city for Hcity. Houston was the fastest to almost two million in 2000. More employee relocations according to a growing city in the United States in the than four million people live in the study by Cendant Mobility. -

Volume 17, No. 1, January 2019

THE TEXAS ROOM DISPATCH A Publication of the Friends of the Texas Room (Incorporated November 27th, 2002) Volume 17, Number 1, January 2019 Monday, January 28th, 2019, Meeting Meeting location is The Julia Ideson Building, Houston Public Library, first-floor auditorium, 500 McKinney Avenue. 6:00 – 6:30 Reception 6:30 Program PROGRAM Dr. W. F. Strong, Fulbright Scholar and Professor of Communication at the University of Texas- Brownsville and native Texan who holds degrees in Communication and Literature from Abilene Christian University and The University of North Texas, will speak on the topic "Special Collections Libraries Preserve Texas Culture, from Linguistics to Folklore to Historical Truths." NEW PAPERLESS PARKING Free parking is available for FTxR members in the garage under the Jones Building accessed from Lamar Avenue. Upon arriving at the garage entrance meter, (1) select language, (2) enter your license plate number, (3) select “All Day Parking $16,” (4) select “Yes” to the question “Do you have a coupon code?,” (5) enter the code: 47683, (6) place the printed receipt on your dashboard. This is a one-time code. No code is needed upon exiting. Non-FTxR members who want to use the underground parking must pay upon entering the HPL Garage. Paper tickets will no longer be issued. Parking is also available in the Smith Garage located at 1100 Smith Street next to Pappas restaurant. The garage entrance is on Smith Street. A parking fee of $5.00 is charged after 5:00 pm. Free parking is also available on the nearby streets after 6:00 pm. -

The Rice Hotel Would Be Safe

Cite Fall 1992-Winterl993 21 The Rice Hotel % MARGIE C. E L L I O T T A N D CHARLES D. M A Y N A R D , JR. i • • ia .bU I I I " f If HE* When Texas was stilt an outpost for American civilization and m Houston was a rowdy geographi- cal gamble, Jesse H. Jones' Rice Hotel came along and showed the ••»*. locals what class was all about. W DENNIS FITZGERALD, Houston Chronicle, 30 March 1975 Ladies' bridge meeting, Crystal Ballroom. Rice Hotel, shortly after opening f sentiment were all that was needed CO the hero of San Jacinto, The nonexistent From the beginning the Rice was a Houston Endowment donated the hotel to guarantee its preservation. Houston's town of Houston won out over more than landmark, one of Houston's first steel- Rice University, which had owned the Rice Hotel would be safe. But 1 5 years a dozen other contenders. The first capitol framed highnse buildings. I en thousand land upon which the building stood since without maintenance have left what was built on the site in 1837. After 1839, people turned up to tour the building on the 1900 death of William Marsh Rice. Imay be our most important landmark in when the seat of government was moved opening day. For two years the hotel continued to ruinous condition. Many Housionians, from Houston to Austin, the Allen opt ran profitably. I" 1974. howev er. the sentimentalists and pragmatists alike, brothers retained ownership of the capitol Through the years, numerous modifica- city of Houston adopted a new fire code, wonder whether their city can live up to its building, which continued to be used lor tions were made. -

The Vernacular Houses of Harlan County, Kentucky

-ABSTRACT WHAT is the vernacular ? Are some houses vernacular while others are not? Traditional definitions suggest that only those buildings that are indigenous, static and handmade can be considered vernacular. This thesis uses Harlan County, Kentucky as a case study to argue that vernacular architecture includes not only those houses that are handmade, timeless and traditional but also those houses that are industrial and mass-produced. Throughout the 19 th century Harlan County was an isolated, mountainous region where settlers built one and two-room houses from logs, a readily available material. At the turn of the century a massive coal boom began, flooding the county with people and company-built coal camp houses which were built in large quantities as cheaply as possible with milled lumber and hired help. Given traditional conceptions of the vernacular, it would have been appropriate to assume the vernacular tradition of house building ended as camp houses, those houses that were not built directly by the residents with manufactured materials, began to replace the traditional log houses. However, the research presented in this thesis concludes that many elements of form, construction and usage that were first manifest in the handmade log cabins continued to be expressed in the county’s mass-produced camp houses. These camp houses not only manifest an evolution of local building traditions but also established qualities of outside influence which in turn were embraced by the local culture. Harlan County’s houses make the case for a more inclusive conception of vernacular architecture. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 6 I. -

Perspecta+21.Pdf

About Perspecta z r Editors Thanks ro Send editorial correspondence ro: Carol Burns The printing of J. Glynnis Berry, Aaron BetsÞy, Liz Bmns, Perspecta ,{rchitecture is not an isolated or Robert Taylor this journal was made Mary Curtain, Stacy Genuni/1, Bolt Goll¿/, P.O. Box zrzr,Yale University autonomous medium; it is actively possible in part by Bi// Grego, Sìanøk Hariri, Richard Hays, New Haven, Connecticut o65zo engaged by the social, intellectual, and genefous gifts from: Design Peter MacKeitlt, and Llnn Ulhalen. visual culture which is outside the Gønnar Birþert¡ Joseþb Gugliettì Send orders and business discipline and which encompasses it. Burgee uitb Special thanks to correspondence to: Jobn Though grounded in the time and place Joseph Bednar Sandra C enterlnooþ Arch i tects of its making, architecture is capable Cloud and Aluin Eisennan The MIT Press Journals Department Robert Taylor Dauid M. Child¡ of reshaping the z8 Carlecon Srreet cultural matrix from Henry Cobb which it rises. A vital architecture The Norfolk projects were aided by a Cambridge, Massachuset ts c2t 'lYaten is one 42 Cox Graphic Production grant from the Graham Foundarion for J, that resonates with that culture. It is Page Rbineiteck Gwathmey Siegel and Assocìates this resonance, not reference Âdvanced Studies in Fine Art. In the Unired Kingdom, conrinenral to some Hehnzt locus left behind or yet Europe, the Middle East and Africa, Jahn to be found, Copy Editor Kohn Pedersen Fox gives Perspecta 2r was designed during send orders and business which architecrure its power. Rutb Hein Herbert McLaughlin 1984 in New Haven, Connecticut. -

Cite 74 29739 Final Web Friendly

TOUR COMPETITION e RDA ANNUAL ARCHITECTURE TOUR t The Splendid Houses of John F. Staub i Saturday and Sunday, March 29 and 30 1 - 6 p.m. each day. c 99K HOUSE COMPETITION . 713.348.4876 or rda.rice.edu 8 LECTURES Rice Design Alliance and AIA Houston 0 The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Brown Auditorium announce finalists. 7 p.m. G 713.348.4876 or rda.rice.edu N SANFORD KWINTER I Far From Equilibrium: Essays on Technology and Design Culture R A program by the MFA,H Bookstore Wednesday, April 2 IN FEBRUARY, FIVE FINALISTS WERE SELECTED FROM 182 and adaptability to reproduction as well as design. P GWENDOLYN WRIGHT entrants proposing a sustainable, affordable house The winner will receive an additional $5,000 New York City that addresses the needs of a low-income family in stipend. The City of Houston through the Land S Co-sponsored by RDA and Houston Mod Wednesday, April 9 the Gulf Coast region. Each will receive a $5,000 Assemblage Redevelopment Authority (LARA) R award and the competition will move forward to initiative has donated a site for the house located at THOM MAYNE, MORPHOSIS Santa Monica, CA Stage II. 4015 Jewel Street in Houston’s historic Fifth Ward, A The 2008 Sally Walsh Lecture Program a residential area northeast of Co-sponsored by RDA and AIA Houston downtown. Once constructed, Wednesday, April 16 D the winning house will be sold or auctioned to a low- BOOK SIGNING income family. N WM. T. CANNADAY Five jurors, representing The Things They’ve Done E A book about the careers of selected graduates expertise in design, sustainabili- of the Rice University School of Architecture ty, construction of affordable L Thursday, April 10 housing, and Houston’s Fifth 5-7 p.m.