Building with Logs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Maintaining the Historic Character of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence

United States Forest Department of Service Agriculture Technology & Development Program A Guide to Maintaining 2300–Recreation April 2014 the Historic Character 1423–2815P–MTDC of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence Cover: This photo in September 1923 shows a newly built recreation residence in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains at the Silver Creek tract of the Rainier National Forest, which is now part of the Mt. Baker- Snoqualmie National Forest in the Pacific Northwest Region. A Guide to Maintaining the Historic Character of Your Forest Service Recreation Residence Kathleen Snodgrass Project Leader USDA Forest Service Technology and Development Center Missoula, MT April 2014 USDA Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, Adjudication, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, D.C. 20250-9410, by fax (202) employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, 690-7442 or email at [email protected]. disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual’s income is Persons with Disabilities derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment Individuals who are deaf, hard of hearing or have speech disabilities and you wish to file either or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases an EEO or program complaint please contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) 877-8339 or (800) 845-6136 (in Spanish). -

Log Buildings

INFORMATION Know your house LOG BUILDINGS Log building in Heidalen. Photograph: M. Boro © Riksantikvaren The Directorate for Cultural HISTORY Heritage is the adviser to Log construction was the main construction Log construction sets great demands on the the Ministry of Climate method for houses in Norway from the Middle carpenter. In the Middle Ages, log construction and Environment on the development of the Ages until the 1900s. Almost every type of build- developed into a highly advanced technique. national cultural heritage ing was constructed using logs, from churches After the 1700s it became common to panel log policy. The Directorate for and houses to cow byres, hay barns and other buildings in the towns and in the coastal districts, Cultural Heritage is also agricultural buildings. The technique was used and eventually in the flatland communities. This responsible for ensuring the implementation of the both in towns and in the country. In inland val- meant that the requirements for log walls were no national cultural heritage leys you will find beautiful preserved log build- longer as stringent. policy and in this context ings with the log walls clearly visible. is responsible for the work of the county councils The design of log buildings has changed over and the Sami Parliament In rural communities in flatland areas of Nor- time. The design of the log heads and the cor- with cultural heritage, way, along the coast and in our “wooden towns”, ners (tenons) are important when establishing cultural environments and the majority of old wooden buildings are the date of a building. -

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

Lost in Coos

LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Golden Falls Publishing LOST IN COOS Other books by Lionel Youst Above the Falls, 1992 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, 1997 with William R. Seaburg, Coquelle Thompson, Athabaskan Witness, 2002 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, (paper) 2002 Above the Falls, revised second edition, 2003 Sawdust in the Western Woods, 2009 Cover photo, Army C-46D aircraft crashed near Pheasant Creek, Douglas County – above the Golden and Silver Falls, Coos County, November 26, 1945. Photo furnished by Alice Allen. Colorized at South Coast Printing, Coos Bay. Full story in Chapter 4, pp 35-57. Quoted phrase in the subtitle is from the subtitle of Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, by Orville Dodge (Salem, OR: Capital Printing Co., 1898). LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thrilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River, Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Including material by Ondine Eaton, Sharren Dalke, and Simon Bolivar Cathcart Golden Falls Publishing Allegany, Oregon Golden Falls Publishing, Allegany, Oregon © 2011 by Lionel Youst 2nd impression Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9726226-3-2 (pbk) Frontier and Pioneer Life – Oregon – Coos County – Douglas County Wilderness Survival, case studies Library of Congress cataloging data HV6762 Dewey Decimal cataloging data 363 Youst, Lionel D., 1934 - Lost in Coos Includes index, maps, bibliography, & photographs To contact the publisher Printed at Portland State Bookstore’s Lionel Youst Odin Ink 12445 Hwy 241 1715 SW 5th Ave Coos Bay, OR 97420 Portland, OR 97201 www.youst.com for copies: [email protected] (503) 226-2631 ext 230 To Desmond and Everett How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. -

Logger Safety Initiative (LSI) Accident Prevention Program (APP) For

Logger Safety Initiative Accident Prevention Program for Cutting Operations Version 1.1 – 7/2014 Instructions This sample program is provided to assist you as an employer to meet the Logger Safety Initiative Accident Prevention Program requirements. The content of this program must be used. However, we encourage employers to add their company specific policies to this program. 1 Version 1.1 – 7/2014 Table of Contents Training Requirements for Cutters 3-4 Safety Policy and Commitment 5 Safety Disciplinary Policy 6 Safety Responsibilities 7-9 General Safety Information and Rules 10-14 Safety Meetings 15 Illness or Injury Procedures and Blood Borne Disease Exposure 16 Employee Safety Orientation and Training Record 17 Cutter Training Curriculum 18 Required Personal Protective Equipment 18 Safe Chainsaw Use 18-19 General Work Procedures 19-21 Falling – Planning 21-23 The Undercut 23 The Backcut 23-24 Unintentional “Dutchman” 24-25 Intentional “Dutchman (Swingcut) 25 Falling Danger Trees 25-27 Common Falling Difficulties 27-29 Leaners 29 Heavy Leaners 29-30 Extreme Leaners with Splits in the Butts 30-31 Falling Against the Lean 31-32 Falling Against the Lean – Using Hydraulic Jack 32 Trees Tied Together 32-33 Hang-ups 33 Windfall and windfall roots 33-34 Burned Timber 34 Bucking 34-35 Bind 35 Pivot Points 35-36 Limbing 36 Boring 36 Cut-up Trees 36 Domino Falling 37 Hazard Communication Program Overview 38 Written Hazard Communication Program 39-40 Outdoor Heat Exposure Safety Program 41-43 Appendix 1 - First Aid Kits 44 Appendix 2 – Emergency -

Conifer Pruning EB1984

EB1984 Donald P. Hanley, Ph.D. Stephen Reutebuch, M.S. Conifer Pruning Conifer pruning is the practice of removing the lower branches from live green conifer trees. Without pruning, the lower branches on conifers, such as Douglas-fir, western larch, and ponderosa pine, may persist for up to 80 years. The primary objective of pruning for wood quality improvement is to produce a small, uniform knotty core throughout the length of the pruned bole so that clear wood volume will be maximized. Achieving this objective may result in increased financial returns to the landowner when the trees are harvested. There are many other benefits from pruning, even if clear wood production or financial concerns are of secondary importance. These include: • Increased understory vegetation for wildlife. As young stands are thinned and the dominant and co-dominant trees are pruned, more light will reach the forest floor, resulting in increased grass, herb, and shrub vegetation over time. This new vegetation often attracts wildlife as forage, browse, and hiding cover. • Reduced fuel ladders. A “fuel-ladder” is the pathway that a fire can travel from the forest floor up to the tree canopy. Unpruned trees in unthinned stands have many low branches that can increase the probability of a fire getting into the tree crowns. Once the fire is in the crown, the likelihood of tree death is high and the probability of rapid fire spread increases. • Reduced incidence of disease. For some diseases, such as the introduced blister rust in white pine, pruning is a primary weapon in reducing the disease spread as blister rust fungi enters the tree through its needles near the ground. -

Franklin, NH, Log House

NEW HAMPSHIRE DIVISION OF HISTORICAL RESOURCES State of New Hampshire, Department of Cultural Resources 603-271-3483 19 Pillsbury Street, 2 nd floor, Concord NH 03301-3570 603-271-3558 Voice/ TDD ACCESS: RELAY NH 1-800-735-2964 FAX 603-271-3433 http://www.nh.gov/nhdhr [email protected] REPORT ON A LOG HOUSE FRANKLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN DECEMBER 5, 2009 This report summarizes observations made during a brief inspection of a log house standing near Webster Lake in Franklin, New Hampshire, on the afternoon of December 1, 2009. The inspection was carried out at the request of the building’s owner, who has conducted considerable research on the property but was seeking an independent evaluation of the significance of the log house. Present at the meeting were Todd M. Workman, the owner, and Peter Michaud and James Garvin of the New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources, the State Historic Preservation Office. The following report represents an initial summary of observations made on December 1, 2009, together with recommendations for further research and evaluation. Summary: The log house was built in that part of Andover, New Hampshire, that became part of the Town (later City) of Franklin when that entity was incorporated in 1828. Apart from a small and much-studied group of sawn-log buildings that survive in the coastal region of New Hampshire and adjacent Maine, this house is currently the only known log dwelling to survive in New Hampshire. As such, the building represents the sole example of a building tradition that was once predominant on the New England frontier. -

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania

Folk Log Structures in Pennsylvania By Thomas M. Brandon Research Assistants: Jonathan P. Brandon and Mario Perona FOLK ARCHITECTURE The term ‘folk architecture’ is often used to draw a distinction between popular or landmark architecture and is nearly synonymous with the terms ‘vernacular architecture’ and ‘traditional architecture.’ Therefore, folk architecture includes those dwellings, places of worship, barns, and other structures that are designed and built without the assistance of formally schooled and professionally trained architects. Folk architecture differs from popular architecture in several ways. For example, folk architecture tends to be utilitarian and conservative, reflecting the specific needs, economics, customs, and beliefs of a particular community. (Source: Oklahoma History Society’s Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, Website. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/encyclopedia/entries/F/FO002.html, Alyson L. Greiner, February, 17, 2011). Note. Much of the data and pictures found in this field guide came from a study on log structures in 18 counties of western and central Pennsylvania. The Historic Value of Folk Log Structures The study of folk log construction, also known as horizontal log construction, is exciting because, unlike most artifacts from the pioneer era, log structures have not been moved from where the pioneers used them. The log structure remains intact within the landscape the pioneer who built it intended. Besides the structure itself, which provides valuable information about the specific people who occupied it, the surrounding historic landscape tells it own story of how the family lived, from location of water sources and family dump to the layout of fields, location with other houses in the neighborhood and artifacts found in the ground still in context with their original use. -

Printable Intro (PDF)

round wood timber framing make an A shape. They can still be found in old barns and cottages. But they had to find very long pieces of wood, so people started making small squares and building them up to the right shape, then joining the squares diagonally to make a roof. By now, everyone was squaring their timber, because a) it's more uniform, and removes uncertaintly; b) all joints can be almost identical – you don't have to take into consideration the shape of the tree; unskilled people can then be employed to make standard joints; and c) right- angles fit better, joints become stronger, and you can fit bricks / wattle & daub in more easily. Everything is flat and flush. what are the benefits? So round wood could be considered old- fashioned, but the reasons for resurrecting it are aesthetic and ecological. It looks pretty; it's a Hammering a peg into a round wood joint with a natural antidote to the square, flat, generic world home-made wooden mallet. that we build; it reconnects people with the forms of the natural world that are more relaxing to the eye; and it reminds us that wood comes from what is it? trees. Also, you can use coppiced wood and Round wood is straight from the tree (with or smaller dimension timber. If you use squared without bark), without any processing, squaring or wood, you need to cut down mature trees and re- planking. Timber framing is creating the structural plant, but a coppiced tree continually re-grows. framework for a building from wood. -

Chapter 12 Review

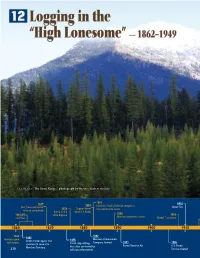

FIGURE 12.1: “The Swan Range,” photograph by Donnie Sexton, no date 1883 1910 1869 1883 First transcontinental Northern Pacifi c Railroad completes Great Fire 1876 Copper boom transcontinental route railroad completed begins in Butte Battle of the 1889 1861–65 Little Bighorn 1908 Civil War Montana becomes a state Model T invented 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1862 1882 1862 Montana gold Montana Improvement Anton Holter opens fi rst 1875 rush begins Salish stop setting Company formed 1891 1905 commercial sawmill in Forest Reserve Act U.S. Forest Montana Territory fi res after confrontation 230 with law enforcement Service created READ TO FIND OUT: n How American Indians traditionally used fire n Who controlled Montana’s timber industry n What it was like to work as a lumberjack n When and why fire policy changed The Big Picture For thousands of years people have used forests to fill many different needs. Montana’s forestlands support our economy, our communities, our homes, and our lives. Forests have always been important to life in Montana. Have you ever sat under a tall pine tree, looked up at its branches sweeping the sky, and wondered what was happen- ing when that tree first sprouted? Some trees in Montana are 300 or 400 years old—the oldest living creatures in the state. They rooted before horses came to the Plains. Think of all that has happened within their life spans. Trees and forests are a big part of life in Montana. They support our economy, employ our people, build our homes, protect our rivers, provide habitat for wildlife, influence poli- tics, and give us beautiful places to play and be quiet. -

Log Cabin Studies: the Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Forestry Depository) 1984 Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest Part of the Architectural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, "Log Cabin Studies: The Rocky Mountain Cabin, Log Cabin Technology and Typology, Log Cabin Bibliography" (1984). Forestry. Paper 4. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/govdocs_forest/4 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Government Documents (Utah Regional Depository) at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forestry by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'EB \ L \ga~ United Siaies Department of Agriculture Foresl Serv ic e Intermountain Region • The Rocky Mountain Cabin Ogden, Utah Cull ural Resource • log Cabin Technology and Typology Re~ o rl No 9 LOG CABIN STUDIES By • log Cabin Bibliography Mary Wilson - The Rocky Mountain Cabi n - Log Ca bin Technology and Typology - Log Cabi n Bi b 1i ography CULTURAL RESOURCE REPORT NO. 9 USDA Forest Service Intennountain Region Ogden. Ut ' 19B4 .rr- THE ROCKY IOU NT AIN CA BIN By ' Ia ry l,i 1s on eDITORS NOTES The author is a cultural resource specialist for the Boise National Forest, Idaho . An earlier version of her Rocky Mountain Cabin study was submitted to the university of Idaho as an M.A. thesis . Cover photo : Homestead claim of Dr. -

Chapter 4 Building the Log House

Chapter 4 Building the Log House In the Woods rees are a renewable resource if Tlogged on a sustainable time schedule of a hundred or more years between harvests. The way to ensure a perpetual source of house logs is selective logging. House logs are best cut in winter, when the sap is down and the logs can be skidded over the snow with minimum damage to the logs and the environment. Bark beetles are dormant in winter, and a long winter drying season may dry the logs enough to keep the beetle Saw safety: use hearing protection and eye population down in the spring. protection when using Bark beetles will not invade dry a chain saw. Never cut logs. with the top part of the Choose trees that are of the tip of the blade. If you do, the saw could kick length and diameter that will suit back into your face. your needs. Think in terms of cutting a matched set of logs with A modern equivalent to horse- the same mid-point diameter. logging is a four wheeler fitted with Leave the remaining trees un- an arched log-carrying frame damaged by traveling lightly on the equipped with a 2,000-pound land as you skid the logs out of the capacity electric winch powered by forest. The trees left behind will the 12-volt battery system of the off- benefit from having more light and road vehicle (see drawing below). space to grow in. An arched log-carrying frame that is pulled by a four-wheeler style all-terrain vehicle.