Leopold Bloom and the Unveiling of the Abject in Joyce's Ulysses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1974.Ulysses in Nighttown.Pdf

The- UNIVERSITY· THEAtl\E Present's ULYSSES .IN NIGHTTOWN By JAMES JOYCE Dramatized and Transposed by MARJORIE BARKENTIN Under the Supervision of PADRAIC COLUM Direct~ by GLENN ·cANNON Set and ~O$tume Design by RICHARD MASON Lighting Design by KENNETH ROHDE . Teehnicai.Direction by MARK BOYD \ < THE CAST . ..... .......... .. -, GLENN CANNON . ... ... ... : . ..... ·. .. : ....... ~ .......... ....... ... .. Narrator. \ JOHN HUNT . ......... .. • :.·• .. ; . ......... .. ..... : . .. : ...... Leopold Bloom. ~ . - ~ EARLL KINGSTON .. ... ·. ·. , . ,. ............. ... .... Stephen Dedalus. .. MAUREEN MULLIGAN .......... .. ... .. ......... ............ Molly Bloom . .....;. .. J.B. BELL, JR............. .•.. Idiot, Private Compton, Urchin, Voice, Clerk of the Crown and Peace, Citizen, Bloom's boy, Blacksmith, · Photographer, Male cripple; Ben Dollard, Brother .81$. ·cavalier. DIANA BERGER .......•..... :Old woman, Chifd, Pigmy woman, Old crone, Dogs, ·Mary Driscoll, Scrofulous child, Voice, Yew, Waterfall, :Sutton, Slut, Stephen's mother. ~,.. ,· ' DARYL L. CARSON .. ... ... .. Navvy, Lynch, Crier, Michael (Archbishop of Armagh), Man in macintosh, Old man, Happy Holohan, Joseph Glynn, Bloom's bodyguard. LUELLA COSTELLO .... ....... Passer~by, Zoe Higgins, Old woman. DOYAL DAVIS . ....... Simon Dedalus, Sandstrewer motorman, Philip Beau~ foy, Sir Frederick Falkiner (recorder ·of Dublin), a ~aviour and · Flagger, Old resident, Beggar, Jimmy Henry, Dr. Dixon, Professor Maginni. LESLIE ENDO . ....... ... Passer-by, Child, Crone, Bawd, Whor~. -

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses Assistant Teacher Haider Ghazi Jassim AL_Jaberi AL.Musawi University of Babylon College of Education Dept. of English Language and Literature [email protected] Abstract Technically accounting, Intertextuality designates the interdependence of a literary text on any literary one in structure, themes, imagery and so forth. As a matter of fact, the term is first coined by Julia Kristeva in 1966 whose contention was that a literary text is not an isolated entity but is made up of a mosaic of quotations, and that any text is the " absorption, and transformation of another"1.She defies traditional notions of the literary influence, saying that Intertextuality denotes a transposition of one or several sign systems into another or others. Transposition is a Freudian term, and Kristeva is pointing not merely to the way texts echo each other but to the way that discourses or sign systems are transposed into one another-so that meanings in one kind of discourses are heaped with meanings from another kind of discourse. It is a kind of "new articulation2". For kriszreve the idea is a part of a wider psychoanalytical theory which questions the stability of the subject, and her views about Intertextuality are very different from those of Roland North and others3. Besides, the term "Intertextuality" describes the reception process whereby in the mind of the reader texts already inculcated interact with the text currently being skimmed. Modern writers such as Canadian satirist W. P. Kinsella in The Grecian Urn4 and playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald in Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) have learned how to manipulate this phenomenon by deliberately and continually alluding to previous literary works well known to educated readers, namely John Keats's Ode on a Grecian Urn, and Shakespeare's tragedies Romeo and Juliet and Othello respectively. -

The Maternal Body of James Joyce's Ulysses: the Subversive Molly Bloom

Lawrence University Lux Lawrence University Honors Projects 5-29-2019 The aM ternal Body of James Joyce's Ulysses: The Subversive Molly Bloom Arthur Moore Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Moore, Arthur, "The aM ternal Body of James Joyce's Ulysses: The ubS versive Molly Bloom" (2019). Lawrence University Honors Projects. 138. https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp/138 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lawrence University Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MATERNAL BODY OF JAMES JOYCE’S ULYSSES: The Subversive Molly Bloom By Arthur Jacqueline Moore Submitted for Honors in Independent Study Spring 2019 I hereby reaffirm the Lawrence University Honor Code. Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 One: The Embodiment of the Maternal Character..................................................... 6 To Construct a Body within an Understanding of Male Dublin ................................................. 7 A Feminist Critical Interrogation of the Vital Fiction of Paternity ........................................... 16 Constructing the Maternal Body in Mary Dedalus and Molly Bloom ..................................... -

The Late Drafts of James Joyceand Malcolm Lowry

WOMEN'SVOICES: THE LATE DRAFTS OF JAMES JOYCEAND MALCOLM LOWRY Sue Vice University ofsheffield This is an examination of points of comparison between the works of James Joyce and Malcolm Lowry in tenns of their pre-publication revisions to their central female characters: Yvonne in Under the Volcano, Molly Bloom in Uiysses. Do Lowry and Joyce have methods of revision in common? Are these women characters affected by such revisions in similar ways? Do they become 'freer' and more dialogmd, in Mikhail Bakhtin's tenns, or is there a negative connection between their linguistic gender and the author's masculinity, the wielding of a blue pen over a textual b*?' And Wy, how do such pre-publication revisions affect the textual construction of femininity which we md in the published form? Can a case be made for such authorial transvestism actually putting into question accepted gender roles, voices and behaviour patterns? To start with Under the Volcano,in Yvonne's case a drama occurs in the five full drafts which Lowry produced over ten years2 It could be seen as Oedipal: the dnuiken Consul's daughter becomes the alcoholic Consul's wife; Hugh, the daughter's boyfriend, becomes the Consul's half-brother and possibly adulterous lover of Yvonne; and Laruelle looms increasingly larger, ñrst as a hoverer over the Consul's daughter, then as another possible lover of his wife. However, what Yvonne's metamorphosis fkom daughter to wife also shows is, ñrst, how Lowry's pracíice involved progressively casíing off the conventional intnisive narrator and allowing the characters to speak for themselves, so that, as Bakhtin would say: "we have a pluraiity of consciousnesses, with equal rights, each with its own world" (Bakhtin 1984, 104). -

James Joyce – Through Film

U3A Dunedin Charitable Trust A LEARNING OPTION FOR THE RETIRED Series 2 2015 James Joyce – Through Film Dates: Tuesday 2 June to 7 July Time: 10:00 – 12:00 noon Venue: Salmond College, Knox Street, North East Valley Enrolments for this course will be limited to 55 Course Fee: $40.00 Tea and Coffee provided Course Organiser: Alan Jackson (473 6947) Course Assistant: Rosemary Hudson (477 1068) …………………………………………………………………………………… You may apply to enrol in more than one course. If you wish to do so, you must indicate your choice preferences on the application form, and include payment of the appropriate fee(s). All applications must be received by noon on Wednesday 13 May and you may expect to receive a response to your application on or about 25 May. Any questions about this course after 25 May should be referred to Jane Higham, telephone 476 1848 or on email [email protected] Please note, that from the beginning of 2015, there is to be no recording, photographing or videoing at any session in any of the courses. Please keep this brochure as a reminder of venue, dates, and times for the courses for which you apply. JAMES JOYCE – THROUGH FILM 2 June James Joyce’s Dublin – a literary biography (50 min) This documentary is an exploration of Joyce’s native city of Dublin, discovering the influences and settings for his life and work. Interviewees include Robert Nicholson (curator of the James Joyce museum), David Norris (Trinity College lecturer and Chair of the James Joyce Cultural Centre) and Ken Monaghan (Joyce’s nephew). -

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce's Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL a Thesis Submitted to the University of Birmingh

Ulysses in Paradise: Joyce’s Dialogues with Milton by RENATA D. MEINTS ADAIL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY English Studies School of English, Drama, American & Canadian Studies College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham October 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis considers the imbrications created by James Joyce in his writing with the work of John Milton, through allusions, references and verbal echoes. These imbrications are analysed in light of the concept of ‘presence’, based on theories of intertextuality variously proposed by John Shawcross, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, and Eelco Runia. My analysis also deploys Gumbrecht’s concept of stimmung in order to explain how Joyce incorporates a Miltonic ‘atmosphere’ that pervades and enriches his characters and plot. By using a chronological approach, I show the subtlety of Milton’s presence in Joyce’s writing and Joyce’s strategy of weaving it into the ‘fabric’ of his works, from slight verbal echoes in Joyce’s early collection of poems, Chamber Music, to a culminating mass of Miltonic references and allusions in the multilingual Finnegans Wake. -

James Joyce and His Influences: William Faulkner and Anthony Burgess

James Joyce and His Influences: William Faulkner and Anthony Burgess An abstract of a Dissertation by Maxine i!3urke July, Ll.981 Drake University Advisor: Dr. Grace Eckley The problem. James Joyce's Ulysses provides a basis for examining and analyzing the influence of Joyce on selected works of William Faulkner and Anthony Bur gess especially in regard to the major ideas and style, and pattern and motif. The works to be used, in addi tion to Ulysses, include Faulkner's "The Bear" in Go Down, Moses and Mosquitoes and Burgess' Nothing Like the Sun. For the purpose, then, of determining to what de gree Joyce has influenced other writers, the ideas and techniques that explain his influence such as his lingu istic innovations, his use of mythology, and his stream of-consciousness technique are discussed. Procedure. Research includes a careful study of each of the works to be used and an examination of var ious critics and their works for contributions to this influence study. The plan of analysis and presentation includes, then, a prefatory section of the dissertation which provides a general statement stating the thesis of this dissertation, some background material on Joyce and his Ulysses, and a summary of the material discussed in each chapter. Next are three chapters which explain Joyce's influence: an introduction to Joyce and Ulysses; Joyce and Faulkner; and Joyce and Burgess. Thus Chapter One, for the purpose of showing how Joyce influences other writers, discusses the ideas and techniques that explain his influences--such things as his linguistic innovations, his use of mythology, and his stream-of consciousness method. -

Ulysses: the Novel, the Author and the Translators

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21-27, January 2011 © 2011 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.1.1.21-27 Ulysses: The Novel, the Author and the Translators Qing Wang Shandong Jiaotong University, Jinan, China Email: [email protected] Abstract—A novel of kaleidoscopic styles, Ulysses best displays James Joyce’s creativity as a renowned modernist novelist. Joyce maneuvers freely the English language to express a deep hatred for religious hypocrisy and colonizing oppressions as well as a well-masked patriotism for his motherland. In this aspect Joyce shares some similarity with his Chinese translator Xiao Qian, also a prolific writer. Index Terms—style, translation, Ulysses, James Joyce, Xiao Qian I. INTRODUCTION James Joyce (1882-1941) is regarded as one of the most innovative novelists of the 20th century. For people who are interested in modernist novels, Ulysses is an enormous aesthetic achievement. Attridge (1990, p.1) asserts that the impact of Joyce‟s literary revolution was such that “far more people read Joyce than are aware of it”, and that few later novelists “have escaped its aftershock, even when they attempt to avoid Joycean paradigms and procedures.” Gillespie and Gillespie (2000, p.1) also agree that Ulysses is “a work of art rivaled by few authors in this or any century.” Ezra Pound was one of the first to recognize the gift in Joyce. He was convinced of the greatness of Ulysses no sooner than having just read the manuscript for the first part of the novel in 1917. -

The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2013 Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses Barbara Nelson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Nelson, Barbara, "Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses" (2013). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 491. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/491 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GETTING ON NICELY IN THE DARK: THE PERILS AND REWARDS OF ANNOTATING ULYSSES By BARBARA LYNN HOOK NELSON B.A., Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA, 1983 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School John Hunt, Chair Department of English Bruce G. Hardy Department of English Yolanda Reimer Department of Computer Science © COPYRIGHT by Barbara Lynn Hook Nelson 2012 All Rights Reserved ii Nelson, Barbara, M.A., December 2012 English Getting on Nicely in the Dark: The Perils and Rewards of Annotating Ulysses Chairperson: John Hunt The problem of how to provide useful contextual and extra-textual information to readers of Ulysses has vexed Joyceans for years. -

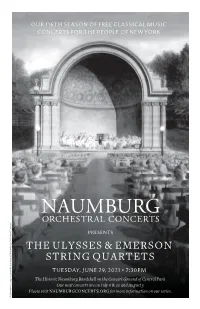

The Ulysses & Emerson String Quartets

OUR 116TH SEASON OF FREE CLASSICAL MUSIC CONCERTS FOR THE PEOPLE OF NEW YORK PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM The Historic Naumburg Bandshell on the Concert Ground of Central Park Our next concerts are on July 6 & 20 and August 3 Please visit NAUMBURGCONCERTS.ORG for more information on our series. ©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing of Naumburg Orchestral of Naumburg Concert©Anonymous, 1930’s gouache drawing TUESDAY, JUNE 29, 2021 • 7:30PM In celebration of 116 years of Free Concerts for the people of New York City - The oldest continuous free outdoor concert series in the world Tonight’s concert is being hosted by classical WQXR - 105.9 FM www.wqxr.org with WQXR host Terrance McKnight NAUMBURG ORCHESTRAL CONCERTS PRESENTS THE ULYSSES & EMERSON STRING QUARTETS RICHARD STRAUSS, (1864-1949) Sextet from Capriccio, Op. 85, (1942) (performed by the Ulysses Quartet with Lawrence Dutton, viola and Paul Watkins, cello) ANTON BRUCKNER, (1824-1896) String Quintet in F major, WAB 112., (1878-79) Performed by the Emerson String Quartet with Colin Brookes, viola III. Adagio, G-flat major, common time -INTERMISSION- DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH, (1906-1975) Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11, (1924-25) Performed with the Ulysses Quartet playing the first parts 1. Adagio 2. Allegro molto FELIX MENDELSSOHN, (1809-1847 Octet in E-flat major, Op. 20, (1825) 1. Allegro moderato ma con fuoco (E-flat major) 2. Andante (C minor) 3. Scherzo: Allegro leggierissimo (G minor) 4. Presto (E-flat major) The performance of The Ulysses and Emerson String Quartets has been made possible by a generous grant from The Arthur Loeb Foundation The summer season of 2021 honors the memory of our past President, MICHELLE R. -

Ulysses, Episode XII, "Cyclops"

I was just passing the time of day with old Troy of the D. M. P. at the corner of Arbour hill there and be damned but a bloody sweep came along and he near drove his gear into my eye. I turned around to let him have the weight of my tongue when who should I see dodging along Stony Batter only Joe Hynes. — Lo, Joe, says I. How are you blowing? Did you see that bloody chimneysweep near shove my eye out with his brush? — Soot’s luck, says Joe. Who’s the old ballocks you were taking to? — Old Troy, says I, was in the force. I’m on two minds not to give that fellow in charge for obstructing the thoroughfare with his brooms and ladders. — What are you doing round those parts? says Joe. — Devil a much, says I. There is a bloody big foxy thief beyond by the garrison church at the corner of Chicken Lane — old Troy was just giving me a wrinkle about him — lifted any God’s quantity of tea and sugar to pay three bob a week said he had a farm in the county Down off a hop of my thumb by the name of Moses Herzog over there near Heytesbury street. — Circumcised! says Joe. — Ay, says I. A bit off the top. An old plumber named Geraghty. I'm hanging on to his taw now for the past fortnight and I can't get a penny out of him. — That the lay you’re on now? says Joe. -

A Shorter Finnegans Wake Ed. Anthony Burgess

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. A SHORTER FINNE GANS WAKE ]AMES]OYCE EDITED BY ANTHONY BURGESS NEW YORK THE VIKING PRESS "<) I \J I Foreword ASKED to name the twenty prose-works of the twentieth century most likely to survive into the twenty-first, many informed book-lovers would feel constrained to· include James Joyce's Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. I say "constrained" advisedly, because the choice of these two would rarely be as spontaneous as the choice of, say, Proust's masterpiece or a novel by D. H. Lawrence or Thomas Mann. Ulysses and Finnegans Wake are highly idiosyncratic and "difficult" books, admired more often than read, when read rarely read through to the end, when read through to the end not often fully, or even partially, under stood. This, of course, is especially t-rue of Finnegans Wake. And yet there are people who not only claim to understand a great deal of these books but affirm great love for them-love of an intensity more commonly accorded to Shakespeare or Jane Austen or Dickens.