Water Reuse and Recycling in Australia- History, Current Situation and Future Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queensland Public Boat Ramps

Queensland public boat ramps Ramp Location Ramp Location Atherton shire Brisbane city (cont.) Tinaroo (Church Street) Tinaroo Falls Dam Shorncliffe (Jetty Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank Balonne shire Shorncliffe (Sinbad Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank St George (Bowen Street) Jack Taylor Weir Shorncliffe (Yundah Street) Cabbage Tree Creek Boat Harbour—north bank Banana shire Wynnum (Glenora Street) Wynnum Creek—north bank Baralaba Weir Dawson River Broadsound shire Callide Dam Biloela—Calvale Road (lower ramp) Carmilla Beach (Carmilla Creek Road) Carmilla Creek—south bank, mouth of creek Callide Dam Biloela—Calvale Road (upper ramp) Clairview Beach (Colonial Drive) Clairview Beach Moura Dawson River—8 km west of Moura St Lawrence (Howards Road– Waverley Creek) Bund Creek—north bank Lake Victoria Callide Creek Bundaberg city Theodore Dawson River Bundaberg (Kirby’s Wall) Burnett River—south bank (5 km east of Bundaberg) Beaudesert shire Bundaberg (Queen Street) Burnett River—north bank (downstream) Logan River (Henderson Street– Henderson Reserve) Logan Reserve Bundaberg (Queen Street) Burnett River—north bank (upstream) Biggenden shire Burdekin shire Paradise Dam–Main Dam 500 m upstream from visitors centre Barramundi Creek (Morris Creek Road) via Hodel Road Boonah shire Cromarty Creek (Boat Ramp Road) via Giru (off the Haughton River) Groper Creek settlement Maroon Dam HG Slatter Park (Hinkson Esplanade) downstream from jetty Moogerah Dam AG Muller Park Groper Creek settlement Bowen shire (Hinkson -

Water for Life

SQWQ.001.002.0382 • se a er WATER FOR LIFE • Strategic Plan 2010-11 to 2014-15 Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority (QBWSA) trading as Seqwater 1 SQWQ.001.002.0383 2010-11 to 2014-15 Strategic Plan Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 Regional Water Grid ......................................................................................................................................... 4 . Seqwater's vision and mission ......................................................................................................................... 5 Our strategic planning framework ................................................................................................................... 5 Emerging strategic issues ................................................................................................................................ 7 Seqwater's goals and strategy for 2010-11 to 2014-15 ................................................................................... 8 • Budget outlook............................................................................................................................................... 10 Strategic performance management ................................................................................................................. 11 Key Performance Indicators .......................................................................................................................... -

Queensland Water Directorate

supporting ellearning splportunities Queensland Water Directorate Demonstrated progress report Funding - up to AUD$l00,000 Submitted September 2008 to the Industry Integration of E-learning business activity of the national training system's e-learning strategy, the Australian Flexible Learning Framework @ Commonwealth of Australia 2008 For more information about E-learning for Industry: Phone: (02) 6207 3262 Email: [email protected] Website: htt~://industrv.flexiblelearninq.net.au Mail: Canberra Institute of Technology Strategic and National Projects GPO Box 826 Canberra ACT 2601 DET RTI Application 340/5/1797 - File A - Document No. 566 of 991 TAFE Queensland - - * Queensland Government Industry integration of e-learning September 08 Progress Report qldwaterand TAFE Queensland 1. Business - provider partnerships numbers and growth In the past business - provider partnerships for trainiug in the water sector have been adhocand there has been little national coordination. Moreover, at the start of this project there were or~lytwo examples of a business - provider partnership for e-learning in the water industry in Australia. These were: a relationship between Wide Bay Water and Sunwater for water worker training and a preliminary arrangement between Wide Bay TAFE and Wide Bay Water to provide on-line training services to other Councils. The collaborative model of industry sector long-term funding has already (in the first three months) resulted in an increase in the number of relationships through two mechanisms. These are: new partnerships as a direct result of the project, and negotiation of partnerships with other RTOs through leverage provided by the project. Two new partnerships have arisen as a result of the industry funding. -

Hydrological Advice to Commission of Inquiry Regarding 2010/11 Queensland Floods

Hydrological Advice to Commission of Inquiry Regarding 2010/11 Queensland Floods TOOWOOMBA AND LOCKYER VALLEY FLASH FLOOD EVENTS OF 10 AND 11 JANUARY 2011 Report to Queensland Floods Commission of Inquiry Revision 1 12 April 2011 Hydrological Advice to Commission of Inquiry Regarding 2010/11 Queensland Floods TOOWOOMBA AND LOCKYER VALLEY FLASH FLOOD EVENTS OF 10 AND 11 JANUARY 2011 Revision 1 11 April 2011 Sinclair Knight Merz ABN 37 001 024 095 Cnr of Cordelia and Russell Street South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia PO Box 3848 South Brisbane QLD 4101 Australia Tel: +61 7 3026 7100 Fax: +61 7 3026 7300 Web: www.skmconsulting.com COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Sinclair Knight Merz constitutes an infringement of copyright. LIMITATION: This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd’s Client, and is subject to and issued in connection with the provisions of the agreement between Sinclair Knight Merz and its Client. Sinclair Knight Merz accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley Flash Flood Events of 10 and 11 January 2011 Contents 1 Executive Summary 1 1.1 Description of Flash Flooding in Toowoomba and the Lockyer Valley1 1.2 Capacity of Existing Flood Warning Systems 2 1.3 Performance of Warnings -

Managing Waste in Your Community Managing Waste in Your Community – Education Kit

Managing Waste in your Community Managing Waste in your Community – Education Kit This information kit has been adapted by the Southern Waste Strategy Authority from fact sheets developed by the Gould League in consultation with EcoRecycle Victoria. The kind permission of EcoRecycle Victoria is acknowledged in publishing this material. Contents Page 1. Introduction 2 2. How to Use the Package 2 3. Fact Sheets 3 3.1 Garbage 4 3.2 Recycling Snapshot 7 3.3 The 3 R’s – Reduce, Reuse & Recycle 11 3.4 Waste Tips 14 3.5 Paper Recycling 16 3.6 Plastic Recycling 19 3.7 Glass Recycling 23 3.8 Steel Can Recycling 25 3.9 Aluminium Recycling 27 3.10 Milk & Juice Carton Recycling 29 3.11 Home Composting 31 3.12 Resources 38 3.13 Key Contacts 40 4. Appendix 42 A. Managing Waste in your Community – Lesson Guide B. Managing Waste in your Community – Student Worksheet C. Managing Waste in your Community – Teacher Worksheet D. Managing Waste in your Community – Cue Cards Managing Waste in your Community – Education Kit ________________________________________________________________________ 1. Introduction What is the Southern Waste Strategy Authority? The SWSA is a Local Government Joint Authority, formed by the twelve southern Tasmanian councils, to implement a comprehensive waste management strategy throughout the region. Based on the widely recognised principles of 'Reduce, Reuse, Recycle', better known as the Waste Management Hierarchy, the strategy aims, amongst other things, to raise community awareness of, and participation in sound waste management practices. Schools can play an important role in this awareness and participation process, through the dissemination of information to students, who will in turn, spread the message into the home and greater community. -

WP 128 Cover & Back

WORKING PAPER 128 Wastewater Reuse and Recycling Systems: A Perspective into India and Australia Gayathri Devi Mekala, Brian Davidson, Madar Samad and Anne-Maree Boland Postal Address P O Box 2075 Colombo Sri Lanka Location 127, Sunil Mawatha Pelawatta Battaramulla Sri Lanka Telephone +94-11 2880000 Fax +94-11 2786854 E-mail [email protected] Website http://www.iwmi.org SM International International Water Management IWMI isaFuture Harvest Center Water Management Institute supportedby the CGIAR ISBN: 978-92-9090-691-9 Institute Working Paper 128 Wastewater Reuse and Recycling Systems: A Perspective into India and Australia Gayathri Devi Mekala Brian Davidson Madar Samad and Anne-Maree Boland International Water Management Institute IWMI receives its principal funding from 58 governments, private foundations and international and regional organizations known as the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). Support is also given by the Governments of Ghana, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka and Thailand. The authors: Gayathri Devi Mekala is a PhD scholar enrolled at the University of Melbourne, Australia. Ms. Mekala’s research is funded by the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and Cooperative Research Centre for Irrigation Futures (CRC IF). She is currently studying the economics of wastewater recycling in Australia and India. Email: [email protected] Brian Davidson is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Resource Management at the University of Melbourne and is also associated with the Cooperative Research Centre for Irrigation Futures. He has over 20 years experience in teaching and researching many different issues in agricultural and resource economics. His research interests lie in understanding and measuring how water markets deliver services to users, how water can be shared amongst stakeholders and how the market failures evident in water and land can be evaluated. -

Water Recycling in Australia (Report)

WATER RECYCLING IN AUSTRALIA A review undertaken by the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering 2004 Water Recycling in Australia © Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering ISBN 1875618 80 5. This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the publisher. Publisher: Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering Ian McLennan House 197 Royal Parade, Parkville, Victoria 3052 (PO Box 355, Parkville Victoria 3052) ph: +61 3 9347 0622 fax: +61 3 9347 8237 www.atse.org.au This report is also available as a PDF document on the website of ATSE, www.atse.org.au Authorship: The Study Director and author of this report was Dr John C Radcliffe AM FTSE Production: BPA Print Group, 11 Evans Street Burwood, Victoria 3125 Cover: - Integrated water cycle management of water in the home, encompassing reticulated drinking water from local catchment, harvested rainwater from the roof, effluent treated for recycling back to the home for non-drinking water purposes and environmentally sensitive stormwater management. – Illustration courtesy of Gold Coast Water FOREWORD The Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering is one of the four national learned academies. Membership is by nomination and its Fellows have achieved distinction in their fields. The Academy provides a forum for study and discussion, explores policy issues relating to advancing technologies, formulates comment and advice to government and to the community on technological and engineering matters, and encourages research, education and the pursuit of excellence. -

Annual Report 2011-12

AnnuAl RepoRt 2011-12 6 September 2012 this Annual Report provides information about the financial and non-financial performance of the Queensland Bulk Water Supply the Hon Mark McArdle Mp Authority (trading as Seqwater) for 2011-12. Minister for energy and Water Supply PO Box 15216 It has been prepared in accordance with the Financial City east QlD 4002 Accountability Act 2009, the Financial and performance Management Standard 2009 and the Annual Report Guidelines the Hon tim nicholls Mp for Queensland government agencies. treasurer and Minister for trade level 9, executive Building the report records the significant achievements against the 100 George St strategies and activities detailed in the organisation’s Strategic Brisbane Qld 4000 and operational plans. this report has been prepared for the Minister for energy and Dear Ministers Water Supply, to submit to parliament. It has also been prepared 2011-12 Seqwater Annual Report to meet the needs of Seqwater’s customers and stakeholders, which include the Commonwealth and local governments, I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2011-12 and industry and business associations and the community. financial statements for the Queensland Bulk Water Supply Authority (QBWSA), trading as Seqwater. this report is publicly available and can be viewed and downloaded from Seqwater’s website at I certify that this Annual Report complies with: www.seqwater.com.au/public/news-publications/annual-reports. • the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and performance Management Standard 2009, and • the detailed requirements set out in the Annual Report requirements for Queensland government agencies. -

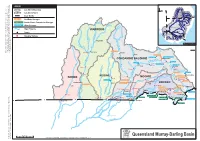

Queensland Murray-Darling Basin Catchments

LEGEND Catchment Boundary Charleville PAROO Catchment Name Roma Toowoomba St George State Border ondiwindi QUEENSLAND Go Leslie Dam SunWater Storages Brewarrina Glenlyon Dam Border Rivers Commission Storages Nygan Cooby Dam Other Storages Broken Hill Menindee NEW SOUTH WALES Major Streams SOUTH WARREGO AUSTRALIA Towns Canberra VICTORIA bury Gauging Stations Al ndigo Be Nive River Ward River Ward Augathella L Murray Darling Basin a Maranoa n g lo R Bungil Ck While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this product, Department Environment and Resource iv River er Neil Turner Weir Disclaimer: completeness or suitability for any particular reliability, Management makes no representations or warranties about its accuracy, purpose and disclaims all responsibility liability (including without limitation, in negligence) for expenses, losses, or incomplete in any way and for reason. damages (including indirect or consequential damage) and costs which you might incur as a result of the product being inaccurate Binowee Charleville Mitchell Roma Chinchilla Weir Creek Gilmore Weir Charleys Creek Weir Chinchilla CONDAMINE BALONNE k gw oo d C Warrego o D Warra Weir Surat Weir Brigalow Condamine Weir C River Creek o Loudon Weir reviR reviR Cotswold n Surat d Dalby a Wyandra Tara m r e i iv n Fairview Weribone e R Ck e Oak ey n Creek n o Cecil Weir Cooby Dam l a Wallen B Toowoomba Lemon Tree Weir NEBINE Cashmere River PAROO MOONIE Yarramalong Weir Cardiff R iv Tummaville Bollon Weir Beardmore Dam Moonie er Flinton River Talgai Weir Cunnamulla -

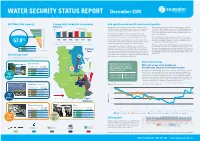

WATER SECURITY STATUS REPORT December 2020

WATER SECURITY STATUS REPORT December 2020 SEQ Water Grid capacity Average daily residential consumption Grid operations and overall water security position (L/Person) Despite receiving rainfall in parts of the northern and southern areas The Southern Regional Water Pipeline is still operating in a northerly 100% 250 2019 December average of South East Queensland (SEQ), the region continues to be in Drought direction. The Northern Pipeline Interconnectors (NPI 1 and 2) have been 90% 200 Response conditions with combined Water Grid storages at 57.8%. operating in a bidirectional mode, with NPI 1 flowing north while NPI 80% 150 2 flows south. The grid flow operations help to distribute water in SEQ Wivenhoe Dam remains below 50% capacity for the seventh 70% 100 where it is needed most. SEQ Drought Readiness 50 consecutive month. There was minimal rainfall in the catchment 60% average Drought Response 0 surrounding Lake Wivenhoe, our largest drinking water storage. The average residential water usage remains high at 172 litres per 50% person, per day (LPD). While this is less than the same period last year 40% 172 184 165 196 177 164 Although the December rain provided welcome relief for many of the (195 LPD), it is still 22 litres above the recommended 150 LPD average % region’s off-grid communities, Boonah-Kalbar and Dayboro are still under 57.8 30% *Data range is 03/12/2020 to 30/12/2020 and 05/12/2019 to 01/01/2020 according to the SEQ Drought Response Plan. drought response monitoring (see below for additional details). 20% See map below and legend at the bottom of the page for water service provider information The Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) outlook for January to March is likely 10% The Gold Coast Desalination Plant (GCDP) had been maximising to be wetter than average for much of Australia, particularly in the east. -

Somerset Dam

ENGINEERS AUSTRALIA ENGINEERING HERITAGE AUSTRALIA HERITAGE RECOGNITION PROGRAM Nomination Document for THE SOMERSET DAM BCC Image BCC-C54-16 Somerset Region South-east Queensland January 2010 Table of Contents Nomination Form .................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction........................................................................................................................................... 2 Letter of support: ................................................................................................................................... 3 Location Maps ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Heritage Assessment 1. BASIC DATA ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE Statement of Significance:.............................................................................................................. 6 Proposed wording for interpretation panel .......................................................................................... 9 Appendix A: Paper by Geoffrey Cossins............................................................................................... 10 References ................................................................................................................................. -

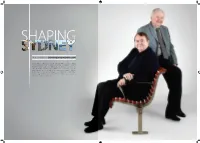

The Story of Conybeare Morrison

THE STORY OF CONYBEARE MORRISON F ew designers have made such an indelible mark on Sydney’s urban spaces, infrastructure and architecture as Darrel Conybeare and Bill Morrison. Together, these two have produced innovations so pervasive through Sydney that they have become part of the ‘furniture’ – yet their significance has largely gone unrecognised. Outdoor Design Source takes a closer look at Conybeare and Morrison’s contribution to the design of the Harbour City and seeks to discover the secret to their extraordinary partnership. 66 LUMINARY I www.outdoordesign.com.au LUMINARY 67 "Their work has subtly and skilfully become part of the fabric of Sydney's metropolitan landscape." Previous page: Bill Morrison n 1962 Darrel Conybeare graduated from the Sydney Park and Parramatta Park. Through this and Darrel Conybeare on their University of Sydney with First Class Honours period he sought to raise consciousness towards SFA classic, The Plaza Seat Iin Architecture winning the prestigious a redesign for Circular Quay. Top left: Mixed-use residential University Medal. He attained a Masters in William Morrison graduated in architecture and commercial towers, Architecture and City Planning at the University at the University of Sydney in 1965. His early Figtree Drive, Homebush of Pennsylvania and went on to work in various years were spent with the Commonwealth Bottom left: Conybeare American architectural practices, including the Department of Works and at the National Morrison’s recent residential esteemed office of Ray & Charles Eames as the Capital Development Commission, Canberra, I was extensive, and given the innovative nature Street Furniture Australia. Founded in 1986 Darling Harbour; George Street North, work, Epping Road, Lane Cove Project Design Director of the National Fisheries which introduced him to a broader vision.