Organizations, Civil Society, and the Roots of Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

728 Merseburg

Personennahverkehrsgesellschaft MDV-Infotelefon 0341 91 35 35 91 Merseburg-Querfurt mbH [email protected] • www.mdv.de Tel. 03461 2899410 | [email protected] www.pnvg.de Merseburg - Querfurt è P 728 gültig ab: 05.07.2021 PNVG Montag - Freitag Fahrtnummer 225 227 107 229 263 111 231 233 235 237 239 121 119 101 Verkehrshinweise s s n s s 52 s s Merseburg, Lessingstr. ab ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 11:50 ... ... Merseburg Süd, A.-Keller-Str. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 11:57 ... ... Merseburg, A.-Dürer-Str. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... Bus 131 aus Ri. Leipzig an 05:57 06:12 06:12 07:27 09:04 10:05 11:05 11:35 12:05 Zug aus Ri. Naumburg an 05:35 06:22 06:22 07:33 08:43 09:44 10:22 11:44 Zug aus Richtung Halle an 05:34 06:34 06:34 07:34 08:34 09:34 10:34 11:34 Merseburg, ZOB Bst. 4 04:40 06:10 ... 06:40 06:40 ... 08:06 09:06 10:06 11:06 12:06 12:10 ... ... Merseburg, Hälterstr. ... ... ... ... Merseburg Nord, Denkmalhof 04:43 06:13 ... 06:43 06:43 ... 08:09 09:09 10:09 11:09 12:09 12:13 ... ... Merseburg Nord, Triebelstr. 04:44 06:14 ... 06:44 06:44 ... 08:10 09:10 10:10 11:10 12:10 12:14 ... ... Merseburg, Merse-Center ... ... 08:12 09:12 10:12 11:12 12:12 ... ... Merseburg, Kaufland ... ... 08:16 09:16 10:16 11:16 12:16 ... ... Merseburg, Gew.gebiet Nord 04:48 06:18 ... 06:48 06:48 ... 08:18 09:18 10:18 11:18 12:18 12:17 .. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

26. Landesliteraturtage Im Saalekreis

26. LANDESLITERATURTAGE ietmars Tinte und Leunas Licht IM SAALEKREIS Veranstaltungen 21. Oktober bis 4. November 2018 26. LANDESLITERATURTAGE ietmars Tinte und Leunas Licht IM SAALEKREIS 21. Oktober bis 4. November 2018 2 IMPRESSUM INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 3 Herausgeber Impressum 2 Landkreis Saalekreis Domplatz 9 Inhaltsverzeichnis 3 06217 Merseburg Grußwort – Kontakt Willkommen zu den 26. Landesliteraturtagen 2018 4 Amt für Bildung, Kultur und Tourismus, SG Kultur und Tourismus Petra Sauerbier Tage der Kinder und Jugendliteratur Telefon: (03461) 40 16 14 • Telefax: (03461) 40 16 02 Veranstaltungen an Schulen und Kindereinrichtungen E-Mail: [email protected] des Saalekreises im Rahmen der 26. Landesliteraturtage 2018 6 www.saalekreis.de • www.landesliteraturtage2018.de Veranstaltungskalender 10 Texte und Redaktion Feierliche Eröffnung der 26. Landesliteraturtage Prof. Dr. Paul D. Bartsch (Halle/Saale) durch den Staats- und Kulturminister des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt Rainer Robra Gestaltung und Landrat Frank Bannert 12 Jörg Wachtel (Brachwitz/Saale) Eröffnungsprogramm Abbildungen der Tage der Kinder- und Jugendliteratur 14 Agenturen, Bundesarchiv, Landesheimatbund Sachsen-Anhalt e. V., Domstiftsarchiv Merseburg, Kulturhistorisches Museum Schloss Merse- Präsentation der 100. Ausgabe der sachsen-anhaltischen burg, Archiv Jankowsky, Siegfried Bauer, Roland Bäge, Maria Brinkop, Literaturzeitschrift «oda – Ort der Augen» 15 Ernst Paul Doerfler, dr.-ziethen-verlag, Nils-Christian Engel, Helmut Henkensiefken, Dirk Hohmann, Cornelia Kirsch, Anna Kolata, «Die Siegfried-Berger-Matinee» 25 Hartmut Krimmer, Landkreis Saalekreis, Peter Lisker, Paul Arne Meyer, Mitteldeutsche Zeitung, Mitteldeutscher Verlag, Jan Möbius, Verleihung des Walter-Bauer-Preises sowie des Mario Schneider, Birgitta Petershagen, privat, Matthias Piekacz, Walter-Bauer-Stipendiums der Städte Merseburg und Leuna Stadtbibliothek «Walter Bauer» Merseburg, Jörg Wachtel, Lutz Winkler unter Schirmherrschaft des Ministerpräsidenten von Sachsen-Anhalt, Dr. -

RADREGION Dübener Heide – Rund Geht‘S Im Biber-, Luther- Und Kneippland

RADREGION Dübener Heide – rund geht‘s im Biber-, Luther- und Kneippland m co e. eid r-h ene ueb rk-d turpa www.na Liebe Bürger und Gäste, wir laden Sie in die Radregion Naturpark Dübener Heide ein. Eingebettet in den natürlichen Fluss- landschaften von Elbe und Mulde mit einer Seenkette im Nordwesten verströmt der größte Misch- wald Mitteldeutschlands die Frische einer eiszeitlich geprägten Hügellandschaft. Im 75.000 Hektar großen Naturpark Dübener Heide können Sie Kranich und Seeadler über roman- tischen Teichen und Seen kreisen sehen. An ihren Ufern thronen zahlreiche Biberburgen. Unter mächtigen Buchen und Eichen glänzt das Moos an reinen Quellen und feuchten Wiesen. Klare Luft kitzelt die Nasen. Wochenende ist Heidezeit. In den Kurorten Bad Düben und dem mit einem Europa-Zertifikat ausgezeichneten Premium-Kneipport Bad Schmiedeberg lassen sich beim Wassertreten oder im Heide Spa die Muskeln entspannen. Kulturfreunde finden in der Lutherstadt Wittenberg, in der Renaissance- und Refor- mationsstadt Torgau, auf der Mitteldeutschen Kirchenstraße oder auf dem neu ausgeschilderten Lutherweg Inspiration. Die 16 Heidemagneten, Ausflugspunkte mit Sehenswürdigkeiten und regionaler Gastronomie, bieten sich für Radpausen an. Unser Motto heißt „Rund geht‘s“. Das bedeutet – von einem einzigen Standort aus ohne Gepäck die Region erkunden. Von sieben Städten aus können 16 Rundtouren in drei verschiedenen Schwierigkeitsklassen (L=Leicht, M=Mittel, S=Schwer) be- fahren werden... und gibt es mal Schwierigkeiten, unsere Rad-Service-Paten helfen Ihnen gerne. Fühlen Sie sich bei uns wohl! Kurstadt Bad Düben Das Tor zur Dübener Heide an der Mulde: Fünf-Mühlen-Stadt, 1000-jährige Burg Düben mit Landschaftsmuseum, interaktive Ausstellung im NaturparkHaus Dübener Heide, Kur- und Wellnesszentrum: Hotel & Resort HEIDE SPA, Kurpark mit Barfuß- und Moorpfad, Rast- platz mit abschließbaren Radboxen für einen unbeschwerten Bummel in die liebevoll sa- nierte Altstadt. -

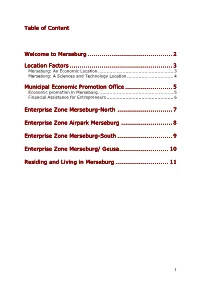

Table of Content

Table of Content Welcome to Merseburg ........................................................................... ................................ ......................2222 Location Factors ................................................................................... ..................... 333 Merseburg: An Economic Location .................................................... 3 Merseburg: A Sciences and Technology Location ................................ 4 Municipal Economic Promotion Office ........................ ........................ 555 Economic promotion in Merseburg.................................................... 5 Financial Assistance for Entrepreneurs .............................................. 6 EnEnEnterpriseEn terprise Zone MerseburgMerseburg----NorthNorth ............................ 777 Enterprise Zone Airpark Merseburg .......................... 888 Enterprise Zone MerseburgMerseburg----SouthSouth ............................ 999 Enterprise Zone Merseburg/ GeusaGeusa.................................................. 101010 Residing and Living in Merseburg ........................... ........................... 111111 1 Welcome to Merseburg The region around Merseburg is an Fraunhofer pilot plant center (PAZ) for industrial location which has polymer synthesis and polymer developed for more than 100 years. processing at Schkopau ValuePark. The chemicals industry set up and Last but not least, due to soft location established on a large-scale its factors e.g. wide-ranging leisure and businesses in neighboring -

Heartland of German History

Travel DesTinaTion saxony-anhalT HEARTLAND OF GERMAN HISTORY The sky paThs MAGICAL MOMENTS OF THE MILLENNIA UNESCo WORLD HERITAGE AS FAR AS THE EYE CAN SEE www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu 6 good reasons to visit Saxony-Anhalt! for fans of Romanesque art and Romance for treasure hunters naumburg Cathedral The nebra sky Disk for lateral thinkers for strollers luther sites in lutherstadt Wittenberg Garden kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz for knights of the pedal for lovers of fresh air elbe Cycle route Bode Gorge in the harz mountains The Luisium park in www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu the Garden Kingdom Dessau-Wörlitz Heartland of German History 1 contents Saxony-Anhalt concise 6 Fascination Middle Ages: “Romanesque Road” The Nabra Original venues of medieval life Sky Disk 31 A romantic journey with the Harz 7 Pomp and Myth narrow-gauge railway is a must for everyone. Showpieces of the Romanesque Road 10 “Mona Lisa” of Saxony-Anhalt walks “Sky Path” INForMaTive Saxony-Anhalt’s contribution to the history of innovation of mankind holiday destination saxony- anhalt. Find out what’s on 14 Treasures of garden art offer here. On the way to paradise - Garden Dreams Saxony-Anhalt Of course, these aren’t the only interesting towns and destinations in Saxony-Anhalt! It’s worth taking a look 18 Baroque music is Central German at www.saxony-anhalt-tourism.eu. 8 800 years of music history is worth lending an ear to We would be happy to help you with any questions or requests regarding Until the discovery of planning your trip. Just call, fax or the Nebra Sky Disk in 22 On the road in the land of Luther send an e-mail and we will be ready to the south of Saxony- provide any assistance you need. -

Amtsblatt Der Stadt Wettin-Löbejün Mit Den Ortschaften Brachwitz, Döblitz, Domnitz, Dößel, Gimritz, Löbejün, Nauendorf, Neutz-Lettewitz, Plötz, Rothenburg Und Wettin

Amtsblatt der Stadt Wettin-Löbejün mit den Ortschaften Brachwitz, Döblitz, Domnitz, Dößel, Gimritz, Löbejün, Nauendorf, Neutz-Lettewitz, Plötz, Rothenburg und Wettin Nr. 9, Jahrgang 3, 18. September 2013 Baumaßnahmen in der Stadt Wettin-Löbejün Sehr geehrte Bürgerinnen und Bürger, Inhaltsverzeichnis wie Ihnen aus meinen Ausführungen in vergangenen Amtsblättern bekannt Erreichbarkeiten Seite 2 - 4 ist, hatte die Stadtverwaltung bei den zuständigen Behörden fristgemäß zum 28.03.2013 die planerisch untersetzten Anträge zur Förderung für die Baumaß- nahmen Erweiterung der Grundschule Nauendorf zur Carl-Loewe-Grundschule Amtlicher Teil und Sanierung der Domäne in Brachwitz, in welche nach Abschluss der Maß- nahme u. a. die Kinder der Kindertagesstätte „Saalepiraten“ wieder betreut Stadt Wettin-Löbejün werden sollen, eingereicht. und Ortschaften Seite 5 Nach zahlreichen Abstimmungsgesprächen zwischen den beauftragten Fach- ingenieuren, den Mitarbeiterinnen der Stadtverwaltung und den zuständigen Informationen Mitarbeitern der jeweiligen Prüfbehörden des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt kann ich Sie nun darüber informieren, dass der Stadt für beide Maßnahmen Beschei- Stadt Wettin-Löbejün Seite 11 de des Landesverwaltungsamtes des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt vorliegen, die die Stadt in die Lage versetzen, mit den Baumaßnahmen zur Erweiterung der Ortschaft Brachwitz Seite 18 Grundschule in Nauendorf zur Carl-Loewe-Grundschule und der Sanierung der Domäne in Brachwitz zu beginnen. In Brachwitz können sich die Bürger bereits davon überzeugen, dass die Ar- Ortschaft Döblitz Seite 19 beiten zur Entkernung des Domänengebäudes begonnen haben. Die dafür er- forderlichen Beschlüsse zur Vergabe der Leistung hatte der Stadtrat der Stadt Ortschaft Domnitz Seite 20 Wettin-Löbejün bereits am 25. Juli 2013 in Erwartung der positiven Bescheide gefasst. Ortschaft Dößel Seite 22 Gleiches gilt für die Erweiterung der Grundschule Nauendorf zur Carl-Loewe- Grundschule. -

Eine Gelungene Premiere Leser, Ich Habe Mich Erster Kreisfamilientag Und Tag Der Offenen Tür Der Kreisverwaltung Sehr Darüber Eigentlich Wollten Ministerpräsident Dr

Saalekreis - Kurier 27. Juli 2013 Nummer 07/2013 7. Jahrgang Mitteilungsblatt für den Landkreis Saalekreis Hochwasser Sachsen-Anhalt-Tag Kultur Pur Am 28. Juni lud Landrat Frank Bannert Unter dem Motto „Sachsen-Anhalt sagt Einen Überblick über Veranstaltungen, (CDU) zu einer Dankeschön-Veranstal- Danke“, war die Stadt Gommern vom Ausstellungen und Kultur im Saalekreis tung an der Marina Mücheln ein. 28. bis 30. Juni 2013 Gastgeber des 17. finden Sie auf... Sachsen-Anhalt-Tages. Seite 3 Seite 6 Seite 6 Liebe Leserinnen und Eine gelungene Premiere Leser, ich habe mich Erster Kreisfamilientag und Tag der offenen Tür der Kreisverwaltung sehr darüber Eigentlich wollten Ministerpräsident Dr. lichkeiten des Merseburger Schlosses und gefreut, dass Reiner Haseloff und seine Frau, laut Proto- erhielten durch die Mitarbeiterinnen und Sie am 14. koll, nur anderthalb Stunden bleiben. Dass Mitarbeiter der Kreisverwaltung nicht nur Juli meiner daraus vier wurden, zeugt davon, dass der fachliche Auskünfte, sondern auch Ge- Einladung Regierungschef unseres Bundeslandes viel schichtliches über das Schloss zu erfahren. zum 1. Kreis- Freude und Interesse am ersten Kreisfami- Wer wollte, konnte es sich im Stuhl des lientag des Saalekreises hatte. Landrates bequem machen oder sich in ein familientag Der Tag begann mit einem Familien- Gästebuch eintragen. Von beidem wurde sowie zum gottesdienst im Merseburger Dom. Erster rege Gebrauch gemacht. Im Schlossinnen- Tag der offe- Höhepunkt war innerhalb der offiziellen hof erlebten die Besucher bei schönstem nen Tür der Kreisverwaltung in Eröffnung, welche durch den Landrat Sommerwetter die Stände der Kommunen und um das Merseburger Schloss Frank Bannert (CDU) sowie dem Minis- und das bunte Unterhaltungsprogramm auf terpräsidenten auf der Bühne im Schlos- der Bühne. -

Discover Leipzig by Sustainable Transport

WWW.GERMAN-SUSTAINABLE-MOBILITY.DE Discover Leipzig by Sustainable Transport THE SUSTAINABLE URBAN TRANSPORT GUIDE GERMANY The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) The German Partnership for Sustainable Mobility (GPSM) serves as a guide for sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions from Germany. As a platform for exchanging knowledge, expertise and experiences, GPSM supports the transformation towards sustainability worldwide. It serves as a network of information from academia, businesses, civil society and associations. The GPSM supports the implementation of sustainable mobility and green logistics solutions in a comprehensive manner. In cooperation with various stakeholders from economic, scientific and societal backgrounds, the broad range of possible concepts, measures and technologies in the transport sector can be explored and prepared for implementation. The GPSM is a reliable and inspiring network that offers access to expert knowledge, as well as networking formats. The GPSM is comprised of more than 140 reputable stakeholders in Germany. The GPSM is part of Germany’s aspiration to be a trailblazer in progressive climate policy, and in follow-up to the Rio+20 process, to lead other international forums on sustainable development as well as in European integration. Integrity and respect are core principles of our partnership values and mission. The transferability of concepts and ideas hinges upon respecting local and regional diversity, skillsets and experien- ces, as well as acknowledging their unique constraints. www.german-sustainable-mobility.de Discover Leipzig by Sustainable Transport Discover Leipzig 3 ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Mathias Merforth Mathias Merforth is a transport economist working for the Transport Policy Advisory Services team at GIZ in Germany since 2013. -

In Der Region Delitzsch / Eilenburg / Schkeuditz

NEWSLETTER 10 APRIL 2016 Ökumenischer Ambulanter Hospizdienst Nordsachsen in der Region Delitzsch / Eilenburg / Schkeuditz Liebe Freunde, Förderer und Unterstützer unserer Arbeit für den Ökumenischen Ambulanten Hospizdienst in Eilenburg, Delitzsch und Schkeuditz, und einigen Berufsjahren im Rettungsdienst be- gann ich ein Berufsbegleitendes Studium der Ge- sundheitswissenschaften- und Wirtschaft an der Fachhochschule Magdeburg-Stendal. Im Anschluss an mein Studium war ich drei Jahre für das Dia- konische Werk Rochlitz tätig. Hier leitete ich eine Einrichtung der stationären und teilstationären Behindertenhilfe und war mit dem Aufbau von Außenwohngruppen für Menschen mit einer geisti- gen Behinderung betraut. Seit dem 1.1.2011 bin ich Geschäftsführer und Einrichtungsleiter der Stiftung „St. Georg-Hospital“. Neben meiner klassischen Ver- waltungsarbeit schöpfe ich viel Kraft und Freude aus dem Zusammenleben und der Gemeinschaft in unserer Einrichtung. Von Beginn an gab es über das Trauercafé eine enge Bindung zum Ökumenischen Ambulanten Hospizdienst. Wir versuchen unseren Bewohnern des Pflegeheims in ihrer letzten Lebens- phase ein guter Begleiter zu sein. Diese Aufgabe, ich möchte heute die Gelegenheit nutzen mich Ih- speziell Sterbebegleitungen, können wir Dank des nen Vorzustellen. Meine Name ist Tobias Münscher- Ambulanten Hospizdienstes mit der entsprechen- Paulig und ich bin seit dem 01.05.2015 mit der Be- den Kraft und Würde gegenüber den Bewohnern reichsleitung Altenhilfe des Diakonischen Werkes erfüllen. An dieser Stelle gilt unser Dank den vielen Delitzsch/Eilenburg beauftragt und trage somit ehrenamtlichen Mitstreitern und vor allem Frau auch die Verantwortung für die Arbeit des Ambu- Stahl als Koordinatorin. lanten Hospizdienstes. Insofern Sie noch weitere Fragen zu meiner Person Nun möchte ich Ihnen ein wenig über mich und oder meiner Arbeit haben, freue ich mich zu jeder meine tägliche Arbeit mitteilen. -

![The Holy Roman Empire [1873]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7391/the-holy-roman-empire-1873-1457391.webp)

The Holy Roman Empire [1873]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Viscount James Bryce, The Holy Roman Empire [1873] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Liniennetz Region Delitzsch 236 Nach Tornau / Söllichau 236 Nach Tornau / Söllichau Partner Im Verbund 238 Nach Bad Schmiedeberg

Liniennetz Region Delitzsch 236 nach Tornau / Söllichau 236 nach Tornau / Söllichau Partner im Verbund 238 nach Bad Schmiedeberg Kossa S2 nach Bitterfeld / Dessau / Wittenberg RE 13 nach Bitterfeld / Dessau / Magdeburg 6 8 3 3 2 236 2 238 235 238 Schnaditz Authausen 6 196 210 232 3 2 236 230 233 236 239 Löbnitz 239239 Tiefensee Bad Düben Delitzsch 223636 Roitzschjora 235 nach Zinna RE505 50 190 207 210 239 Zuglinie mit Liniennummer 204 210 235 Görschlitz Pressel S1 196 23023 S-Bahnlinie mit Liniennummer 192 203 204 Sausedlitz 0 5 RE 13 3 Tramlinie mit Liniennummer 209 211 22333 2 04 22363 258 Buslinie mit Liniennummer 212 213 6 6 Pohritzsch Zaasch Wellaune 232 3 135 786 Anfangs- bzw. Endhaltestelle 220303 S2 Laue 2 236 Reibitz 210 755 nach Torgau Es gelten die Beförderungsbedingungen und Tarif- Benndorf 210 S4 nach Torgau / bestimmungen der Verkehrsunternehmen im MDV. Glaucha Hoyerswerda Für Ziele außerhalb des Verbundgebietes (Haltepunkte 2 Wöllnau 204 04 Laußig RE 10 nach Torgau / mit * nach dem Ortsnamen) erhalten Sie Informationen 2233 SV-C SV-C 230 231 bei den Verkehrsunternehmen. 196 33 236 Falkenberg /Cottbus SV-C Zschernitz 202 229 nach Audenhain Spröda Badrina Delitzsch 210 Hohen- 229 Noitzsch 0 Gräfen- Doberstau prießnitz 3 Wildenhain 234 2 230 dorf 220303 Unterer Bf. SSV-DV-D 221313 221 203203 Schenken- Beerendorf 232 1 2202 4 0 berg SV Brinnis 221313 2 Gruna Rote Jahne 2 Lindenhayn 3 209 2 221 S9 nach Halle -D 2 234 S9 V SSV-D Battaune 5 1 220909 230 5 3 7 Klitschmar Kyhna Oberer 221 755 196 Krippehna 2 231 1 755 nach Bf.