STEP REPORT 05-2004 Knowledge Intensive Service Activities and Innovation in the Norwegian Aquaculture Industry - Part Project Report from the OECD KISA Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facts About Vesterålen

FACTS ABOUT VESTERÅLEN Vesterålen is a cluster of remarkable and 13th centuries the stockfish trade years old. A dark mineral, resembling land. From the mountains at Sellevoll you islands, located 200 km within the with Bergen started, and caused a tran- Gabbro is found at Åsanfjorden in the Bø may see how the mounds form a pattern Arctic Circle. 35.000 people live in this sition to money-based economy. One of municipality, dated back some 3500 mill. looking like a flat cone-shaped cake. The archipelago of unspoiled beauty. the consequences was a change in the years. More recent minerals (400–600 Bog-Ashpodel with beautiful yellow flo- Westwards, facing the Norwegian population pattern, increasing the num- mill. years) are found on Andøya, betwe- wers grow on the poor marshland. The sea; a ragged alpine landscape of ne- ber of people in the fishing districts. The en Dverberg and Skogvollvatn, and a common trees in Vesterålen are Birch, edlesharp peaks. To the east; the wa- later Middle Ages was a period of narrow zone of even younger minerals Roan and Willow. European Bird Cherry terways of the coastal express stea- growth, caused by the stockfish trade (100–150 mill years) between Ramså and Grey-Alder are relatively rare, and mer, bordered by wide beaches and with the Hanseatic League. At this time and Haugnes, the latter the most recent pines are planted in parts of the region. small communities huddled closely people started to settle in villages, such mineral found ashore in Norway. Rich de- Sigerfjord is famous for the beautiful villa together. -

MOSKENES GUIDE 2008 T Moskenes in 1120, King Eystein Estab Eystein King 1120, in Control

MOSKENES Area: 118.6 km2 Population: approx.1128 Municipal centre: Reine he island of Mosk enesøy is located in the untamed, western part of the Lofoten Is- Page lands. On the far side of the island, you will find long, chalk-white beaches. The island Tis surrounded by strong tidal currents like the Sundstraumen strait, and the infamous 28 Maelstrom. Glaciers and other forces of Nature have sculpted the island landscape, which is among the wildest and most fascinating that Norway can offer. Traces of Stone Age settlement dating back over 5,500 years can be found on the island. Several old place names, such as Moskenes, bear witness to early Sami settlement. The inhabitants of Moskenesøy live largely on the eastern side of the island, where the best harbour conditions are to be found. Earlier, there was also settlement along the entire northern coast of the island – the so-called outer coast, but owing to poor harbour conditions and perilous waters, all of them have now been abandoned. Å, Hamnøy and Sakrisøy are particularly well-known for their old, well-preserved architectural environment. The Lofoten Fishery, the Fishing Village and the Rorbu Cabin Abundant Resources in the North When the great glaciers receded from our northern coastlines, the cod began its annual migra- tion from the Barents Sea to spawn in the waters of Lofoten. Every winter for over 10,000 years, the coastal people have caught the tasty Norwegian Arctic cod, eating the fresh fish together with the liver and roes, or producing stockfish and cod liver oil - used for bartering and trading purposes. -

Artists Are Shaking up Norway's Cod-And-Knitwear Image in the Lofoten Archipelago, but There Are Still Cosy Cabins to Hole Up

ROCKING IN THE ISLES ARTISTS ARE SHAKING UP NORWAY’S COD-AND-KNITWEAR IMAGE IN THE LOFOTEN ARCHIPELAGO, BUT THERE ARE STILL COSY CABINS TO HOLE UP IN AND PLATTERS OF SEAFOOD FOR SUPPER. BY SOPHIE CAMPBELL. PHOTOGRAPHS BY YADID LEVY The fishing village of Reine, on Moskenesøya in the Lofoten Islands 90 f you are a cod, these are the killing fields. Bunches of drying fish twist in the wind on birch frames the size of Dutch barns, and chunky working boats bristle with radar, net winches and fish-finding gear. If you are an artist, this is a land of light, clear and simple, which is why so many have made their way here in the past century and a half. If you are a visitor, this is where mountains shoot Iout of the sea like fins, their reflections diving to unfathomable depths in the fjords, and sweet little wooden houses cluster in shades of lemon and dove and brick and sky. But you mustn’t look too hard in case you fly off roads raised to let meltwater flow away and edged only with flimsy red poles. The Lofoten Islands barely qualify as an archipelago. They are more like a vestigial tail off the coast of Norway, 100km above the Arctic Circle and 230km south of Tromsø, connected to the mainland by a bridge about a kilometre long. More bridges swoop between the seven main islands, and around them skitter innumerable rocks and skerries. Fish is everywhere. It glints through the history and swims through the art. -

Trip to Lofoten

7ULSWR/RIRWHQ :KHQ29th June --- 5th July :KRXiaomeng, Jinghai and my colleague Darius couple. Starting from Trondheim, we drove our Toyota on a one-week trip along the northern part of Norway, to Lofoten and return. Lofoten is said to be one of Norway’s most scenic holiday des- tinations, where you can see towering mountains with pointed peaks standing right in the mid- dle of the sea. It is an archipelago in the ocean, north of the Article Circle. I will describe my journey in a considerably detailed way, so that others can follow some of the trip if they want to. In the summer, when the mid- night sun is there, it’s almost daylight all through the night, so we decided to drive all the way from Trondheim to Lofoten within one day. We started early morning in Trondheim, headed north on E6 towards Bodø. E6 is relatively easy to ride but still there are lots of turns in the mountain roads. The terrain is quite hilly and most of the time, we were either up or down the mountain. The landscape along the road was quite pleasant, green woods, wild flowers and snow mountain peaks. When we were approaching the Arctic Circle, the landscape changed into an untamed wideness. It was such a unique place, so we decided to have a stop over on our way back from Lofoten. We arrived in Bodø just at the right time for the afternoon ferry from Bodø to Moskenes, which is situated in the southern part of the lofoten islands. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

Lofoten Islands Guided Walking Holiday

Hike Norway's Wild Lofoten Islands Tour Style: European Centre Based Destinations: Norway & Scandinavia Trip code: LTLCL 2 & 4 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Far above the Arctic Circle, the Lofoten Islands spill out into the Norwegian Sea. This land of majestic mountains, plunging fjords and wave-swept beaches is a wonderful wilderness of staggering natural beauty. The warm waters of the Gulf Stream give the islands a much milder climate than other areas which sit at the same latitude, so the summer months are the perfect time to walk and be at one with the natural world. In summer, the daylight hours are long; from late May to mid-July the islands are bathed in the wonderful light of the midnight sun. There are two guided walks to choose from each day taking in the wild coast with its white sandy beaches, areas of mountain and charming fishing villages with their traditional ‘rorbuer’ (fishermen’s cabins). The week is based on the island of Austvågøya and includes travelling by ferry to the neighbouring islands of Hadseloya and Skrova. The area is home to sea eagles and whales; it is not unusual to spot these while out walking. Later in the season, as the nights draw in, there is always the chance of seeing the Northern Lights, adding an extra bit of magic to a wonderful destination. WHAT'S INCLUDED • Half Board - buffet breakfast and evening meal • Transport to and from the walks • A full programme of guided walks with 2 options every walking day www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 • The services of experienced -

Scandinavia and Arctic 2020

SCANDINAVIA AND ARCTIC 2020 NORWAY SWEDEN DENMARK FINLAND BALTICS RUSSIA ICELAND FAROE ISLANDS GREENLAND SPITSBERGEN www.nordictravel.com.au [email protected] 1300 702 833 (02) 9904 5424 Iceland driving distances Greenland flight times Keflavík Airport – Reykjavík 55km Narsarsuaq – Nuuk 1hr 15mins Reykjavík – Isafjörður 388km Nuuk – Kangerlussuaq 55mins Isafjörður – Akureyri 513km Kangerlussuaq – Ilulissat 45mins Akureyri – Husavík 90km Ilulissat – Narsarsuaq 5hrs 55mins Husavík – Seyðisfjörður 245km Seyðisfjörður – Höfn 212km Höfn – Vík 272km Vík – Selfoss 129km Selfoss – Blue Lagoon 90km Blue Lagoon – Keflavík Airport 18km GREENLAND Hólmavík • • Akureyri Varmahlíð • Lake Mývatn • Seyðisörður Egilsstaðir • • • Stykkisholmur Uummannaq ICELAND • • Illulissat Reykholt • Aasiaat • Borgarnes Sisimiut • Geysir Gullfoss Vatnajökull • Kangerlussuaq •• • Höfn • Reykjavík þingvellir • Maniitsoq • • Jökulsárlón • • Kulusuk Keavík Skaftafell • • • • Hveragerði • Nuuk Kirkjubæjarklaustur Paamiut • • Narsarsuaq Seljalandsfoss Narsaq • • 50km • 500km Skógafoss • • Vík Qaqortoq• Faroe Islands driving distances Vágar Airport – Tórshavn 47km SPITSBERGEN Tórshavn – Kirkjubøur 11km Tórshavn – Klaksvík 75km Tórshavn – Gjógv 64km Ferries Tórshavn – Vestmanna 39km Helsinki to St Petersburg Klaksvík – Kunoy 12km Helsinki to Tallinn Klaksvík – Viðareiði 19km Helsinki to Stockholm Copenhagen to Oslo Ferries and sub-Sea tunnels Viðareiði Mikladalur • Bergen to Kirkenes (which is the Hurtigruten coastal ferry route) Sørvágur to Mykines Gjógv • • North Cape -

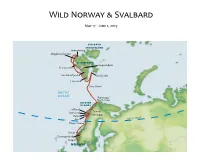

2019 Wild Norway & Svalbard Field Report

Wild Norway & Svalbard May 17 - June 2, 2019 SVALBARD ARCHIPELAGO Smeerenburg Magdalenefjorden SPITSBERGEN Longyearbyen Poolepynten Van Mijenfjorden Storfjorden Hornsund Bear Island ARCTIC OCEAN Skarsvaag/ North Cape LOFOTEN ISLANDS Trollfjord Stamsund Tromsø Kjerringøy Reine CLE Røst ARCTIC CIR Husey/Sanna Runde Geirangerfjord Bergen NORWAY Sunday, May 19, 2019 Bergen, Norway / Embark Ocean Adventurer Unusual for Bergen, it was a dry, warm, and sunny weekend when we arrived here to begin our travels in Wild Norway and Svalbard. Bergen experiences only five rain-free days a year, and this exceptional weather was being fully enjoyed by the locals, especially as this was also the Norwegian National Day holiday weekend. We set out on foot early this morning, for a tour of the old wharf-side district of Bryggen with its picturesque and higgledy-piggledy medieval wooden houses, their colorful gables lit up by today’s bright sunshine. Next, we boarded coaches which took us to Troldhaugen, the home of Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg for over 20 years. The hut where he did much of his work still stands on the lakeside at the foot of the garden. We were treated to an excellent piano recital of some of Grieg’s music before we went to lunch. All too soon, it was time to return to Bergen where our home for the next two weeks, the Ocean Adventurer, awaited us. Once settled in our cabins, our Expedition Leader, John Yersin, introduced us to his team of Zodiac drivers and lecturers who would be accompanying us on our journey over the next two weeks. -

Den Verdifulle Kystkulturen I Nordland

RAPPORT Riksantikvaren er som direktorat for kultur minne forvaltning Den verdifulle kystkulturen i Nordland Miljøverndepartementets rådgivende og utøvende – med kulturarven som ressurs for utvikling faginstans for forvaltning av kulturminner og kulturmiljøer. Direktoratet skal gi faglige bidrag til departementets arbeid med kulturminnevern. Riksantikvaren har ansvar for at den statlige kulturminne- politikken blir gjennomført, og har i denne sammenheng et overordnet faglig ansvar for den regionale kulturminne- forvaltningens arbeid med kulturminnevern. Besøksadresse: Dronningensgate 13, 0152 Oslo Postadresse: Postboks 8196 Dep. N-0034 Oslo, Telefon: (+47) 22 94 04 00 Telefaks: (+47) 22 94 04 04 e-post: [email protected] Sammendrag Nordland fylkeskommune har gjennom- å bygge opp kompetanse og kunnskap om nå ny kunnskap om hvordan kulturarven kan ført et verdiskapingsprogram for kulturmin- kulturarvens betydning for utvikling. være en ressurs for utvikling. Delmålene med ner, Den verdifulle kystkulturen i Nordland, den nasjonale satsingen er oppnådd gjennom: i perioden 2005-2010. Satsingen har vært Gjennom casene er mange bygninger restau- • bruke kulturarven som ressurs til beste for pilotprosjekt i det nasjonale verdiskapingspro- rert med ny bruk som mål. I Lofoten er 24 befolkning, næringsliv, og lokalsamfunn grammet på området, igangsatt av Miljøvern- istandsettingsprosjekter gjennomført. Dette gjennom lokale prosesser, holdningsendrin- departementet og drift et av Riksantikvaren. involverer 27 bygninger, ei Listerskøyte, ei ger hos befolkning og virkemiddelapparat, Lofoten og Vega var prosjektområder frem gammel ferge og 7 historiske hager. I fl ere av styrket lokal identitet og ikke minst bedre Innhold til utvidelse av området i 2009. Da ble Rog- prosjektene er ytterligere bygg satt i stand uten samarbeid mellom virkemiddelaktørene nanfj æra, Nyksund, Meløygården og Kjeøy støtte fra verdiskapingsprogrammet fordi ei- • kulturarven er tatt bedre vare på gjennom SAMMENDRAG ............................................................................... -

Authentic Nordic Experiences ��� ���� A���

Authentic Nordic experiences A p40 p40 SALAD NLAND Longyearbyen p34 LAND Reykjavík Nuuk p32 Tórshavn ARCTIC CIRCLE ARCTIC CIRCLE A SLANDS p26 p16 NLAND p10 SDN NA p46 Oslo Helsinki SSA Tallinn Stockholm SNA p50 p22 Riga LAA Moscow DNA Copenhagen LANA Vilnius Contents SYMBOLS IN THIS BOOK 01 Our world, our regions: about 50 Degrees North The symbols below are used throughout this booklet. Leave 01 Welcome to authentic travel this page folded out as you thumb 03 Travelling in our region through the pages to access the information on this page. 04 Travel style 05 Nordic accommodation 06 Nordic food Tour/Drive 07 Norway 11 Norway guide Winter 13 Sweden 17 Sweden guide Summer 19 Denmark 20 Denmark guide Highlight 23 Finland 27 Finland guide 29 Faroe Islands Sights 31 Faroe Islands guide 33 Iceland Great idea 37 Iceland guide 39 Greenland & High Arctic Daylight hours at 43 Greenland & High Arctic guide winter/summer equinox 45 Russia 47 Russia guide Temperatures: average winter/summer 49 Baltics 51 Baltics guide Temperature ranges and daylight hours are 53 Temperature ranges and daylight hours marked on the maps. 53 Book with us They are marked in order as: winter/summer ranges as a guide for that approximate area. Full temperature and daylight hours tables are featured on page 53. Please speak to us about what clothing and gear to bring on your Nordic experience. Our world, our regions 50 Degrees North is a tour operator that specialises in holiday travel to Northern Europe: Scandinavia, Finland, Iceland, Greenland, the Arctic, the Baltic states, and Russia. -

The Best of the Arctic

THE BEST OF THE ARCTIC SVALBARD NORWAY ICELAND GREENLAND & CANADA NEW! FABLED LANDS ABOARD NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC EXPLORER AND NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ORION I 2019/2020 TM DEAR EXPLORER, There are 8 countries that have territory in the Arctic—defined as land and sea north of 66º 33’N latitude. And between May and September 2019 our two polar vessels, National Geographic Explorer and National Geographic Orion will explore all of the sea-bordering countries. Only Finland and Sweden have landlocked Arctic terrain. Just to give some scale to this vast wilderness: ⊲ Population approx. 1.35 people per square mile in the Arctic ⊲ Population approx. 74,000 people per square mile in Manhattan Using the Manhattan comparison really puts the Arctic into perspective: it’s literally the wildest place on Earth to still have some form of permanent human settlement. What it has in abundance there, however, is non-human life. Plankton-rich seas, great colonies of seabirds, bears—polar bears in some parts and brown bears in others—seven different species of pinnipeds including the great walrus; musk oxen; reindeer in some areas; and whales of many different kinds. There are indigenous people who merit our interest and deserve our admiration, as they conduct their lives in what is, for about half the year, the harshest of possible environments. There are the great mountain ranges and icebergs, some the size of 12 government buildings. And of course, there is the ice—the sea ice which provides hunting grounds for polar bears and pupping grounds for seals. The Arctic is an AWESOME part of our planet, which ideally, every human being should, at some point in their lives, experience. -

Nyksund – Stedet Som Nektet Å Dø

FAKULTET FOR HUMANIORA, SAMFUNNSVITENSKAP OG LÆRERUTDANNING INSTITUTT FOR SOSIOLOGI, STATSVITENSKAP OG SAMFUNNSPLANLEGGING Nyksund – Stedet som nektet å dø Hvilke prosesser kan bidra til å forklare hvorfor det ikke-moderniserbare fiskeværet Nyksund er i ferd med å bli transformert til et postmoderne ”turistvær”? Brynjar Michailoff Pettersen Masteroppgave i Stedsutvikling SPL 6900 Mai 2013 Innhold Innhold .................................................................................................................................................... 2 Forord ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Kapittel 1. Innledning og introduksjon av stedet .................................................................................... 6 1.2 Tema og problemstiling ................................................................................................................. 7 1.2.1 Problemstilling ........................................................................................................................ 8 1.2.2 Forskningsspørsmål ................................................................................................................ 8 1.3 Sosiokulturell analyse .................................................................................................................... 8 1.3.1 Metode og kilder ...................................................................................................................