Between L.S. Lowry and Coronation Street: Salford Cultural Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Ways and My Days

ROBERT ROBERTS BORN 1839 —DIED 1898 AUTOBIOGRAPHY with an APPENDIX by ( C C. WALKER Former Editor of "The Christadelphian" 0 n "** . I ROBERT ROBERTS (From a photograph taken in 189S) Printed and bound in Great Britain by R. J. Acford, Chichester, Sussex. J D PREFACE D HE first thirty-six chapters of this book consist T of an autobiography, under the heading of "My Days and My Ways," that originally appeared in a little monthly magazine called Good Company (1890-1894). The volumes of this have long been out of print. The remaining seven chapters of the book consist of An Appendix concerning " His Days and His Ways," from 1871 to 1898, when he died. This part of the story is of necessity told very briefly, and with some scruples concerning a few left in the land of the living The writer hopes he may be pardoned if anything is thought to be amiss. He aims only at a truthful record, without " malice aforethought " to any living soul. The portrait is from an excellent photograph taken at Malvern in 1895. Q- CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I.—BIRTH AND BOYHOOD .. .. .. 1 II.—" CONVERSION "—Elpis Israel .. .. 7 III.—BAPTISM .. .. .. .. 12 IV.—WRITES TO DR. THOMAS .. .. .. 17 V.—BECOMES A REPORTER .. .. .. 21 VI.—HUDDERSFIELD AND HALIFAX , . 28 VII.—WORKING WITH DR. THOMAS .. .. 34 VIII.—DEWSBURY .. .. .. ..43 IX.—MARRIAGE .. .. .. .. 45 X.—DIETETICS ! .. .. .. .. 53 XI.—INTRODUCING THE TRUTH (HUDDERSFIELD) .. 59 XII.—PUBLIC EFFORT AT HUDDERSFIELD .. 64 XIII.—A BRUSH WITH ATHFISM .. .. 69 XIV.—LEEDS : FOWLER AND WELLS .. .. 74 XV.—BIRMINGHAM : THE FOWLER AND WELLS COMPANY .. .. .. .. 80 XVI.—BIRMINGHAM, LEICESTER, NOTTINGHAM, DERBY . -

Coronation Street Jailbirds

THIS WEEK Coronation Street’s Maria Connor is released from prison this week J – and ex-lover Aidan should beware, says actress Samia Longchambon CORONATION STREET AILBIRDS Maria Connor is by no means the first he view from Maria Connor’s window is by him? After all, it was only a couple of weeks almost tear-jerkingly romantic. It’s ago that her cellmate was remarking, a little Weatherfield woman to end up behind bars… Christmas Eve 2016 and, as if on cue, CORONATION ominously, “Men, eh? Can’t live with ’em, can’t plump white snowflakes have begun to STREET, smash ’em in the head with an iron bar…” DEIRDRE RACHID 1998 T Wrongly convicted of fraud after flutter gently to the ground. Could she have MONDAY, ITV “She does love Aidan,” says Samia. “It wished to gaze out on a more festive scene? hasn’t just been a sexual thing. He’s been her being set up by her fiancé, conman Well, yes, she could. For one thing, she knight in shining armour, her hero.” Jon Lindsay. The injustice sparked a could have wished for the window not to have And yes, he was certainly a tower of strength real-life Free The Weatherfield One campaign. Prime Minister Tony Blair thick iron bars across it. when an innocent Maria found herself falsely even raised it in Parliament. Yes, this was the night a frightened, despairing Maria accused of murder, back in November. But when it began a 12-month prison sentence for an illegal came to the day of her sentencing for this crazy HAYLEY CROPPER marriage, joining a long and illustrious line of marriage scam, for which she pleaded guilty, (NÉE PATTERSON) 2001 Coronation Street women who, over the years, have Aidan tarnished his image by failing to show. -

Department of Economic and Social History

HS3112/EH3612 The life and times of George Orwell 1903-50 Academic session 2003/04 SCHOOL OF HISTORICAL STUDIES The Life and Times of George Orwell 1903-50 A moral history of the first half of the 20th century Module Description Eric Blair was born on 25 June 1903 at Motihari, in Bengal, and died of pulmonary tuberculosis at University College hospital London on 26 January 1950. This is his centenary year. The life he lived was mainly a writer’s life but it was also an active life where he got involved in the things that mattered to him. ‘Getting involved’, and then writing about it, Blair did in the guise of ‘George Orwell’. Blair was an intensely serious and well-read man who in his guise of George Orwell pretended not to be. Instead he pretended to be ordinary, and it was as the ordinary and broadest Englishman that he put his moral self on the line. Orwell’s literary achievements alone would have made him interesting to historians. But in the personality he adopted, and in the moral issues he was interested in, and faced down, Orwell was more than a good writer. He is a way into the century’s dilemmas. This module considers Orwell in history. It considers also the moral and political battle over his reputation. Module Objectives We will endeavour to learn something of Orwell’s life and times; to reflect critically on those times; to read selected works by Orwell and about him; to discuss the moral issues of his day; to understand that there are varieties of ways of interpreting those issues and the history behind them; to construct arguments and deploy supporting data; and most importantly to write and talk about all these things clearly and accurately - much as Orwell himself tried to do. -

The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century Free

FREE THE CLASSIC SLUM: SALFORD LIFE IN THE FIRST QUARTER OF THE CENTURY PDF Robert Roberts | 288 pages | 07 Dec 1990 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140136241 | English | London, United Kingdom The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century by Robert Roberts Today's Date: October 14, Pages: 1 2. Although essentially, the nature of slum life was quite dismal, especially by modern standards, it should be remembered that there also some less grim aspects, particularly after the First World War. It is certainly not a romanticized portrait of slum life in Edwardian England, but it does present a deeper understanding of the causes as well as outcomes of many of the problems which included extreme poverty, lack of employment, illiteracy, ill health, and other social maladies. The nature of life in a slum such as that of Salford was harsh and constantly changing. One usually was not sure whether or not there would be enough money left for food from day to day. The employment situation was grim and while some could find work that might last for an extended period, they could expect to be terminated and unable to find employment elsewhere at some point. Since the cost of living, which included mostly food, was so high, families often did not have many luxuries and many homes were almost bare since there was not money for anything except sustenance. They made do with boxes and slept in their clothes and in what other garments they could beg or filch. Of such people there were millions. It is striking to realize that there were literally millions of people in such a category and at one point, Roberts figures that 50 percent of the population in industrial cities were this class of destitute unskilled workers Aside from general employment and financial problems, the health of people living in Salford was terrible and before the Great War, there was the widespread practice of selling rotting The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century for cheaper prices and thinning out beer with water or worse, formaldehyde. -

Survey Report

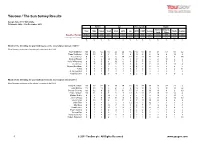

YouGov / The Sun Survey Results Sample Size: 1767 GB Adults Fieldwork: 20th - 21st December 2011 Gender Age Social grade Region Rest of Midlands / Total Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland South Wales Weighted Sample 1767 859 908 214 451 604 498 1007 760 226 574 378 435 154 Unweighted Sample 1767 837 930 68 509 706 484 1154 613 180 632 374 418 163 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Which of the following do you think has been the most stylish woman of 2011? [Don't knows and none of the above's removed, N=1203] Kate Middleton 50 46 54 50 42 44 65 50 50 56 48 53 50 42 Pippa Middleton 10 15 5 4 11 11 9 10 9 5 12 9 10 8 Helen Mirren 9 6 12 3 5 14 12 9 10 11 12 6 8 14 Emma Watson 7 9 6 14 10 6 3 9 5 6 8 10 5 6 Holly Willoughby 6 6 5 3 10 6 3 5 7 6 5 5 7 7 Cheryl Cole 5 7 4 14 5 5 2 4 7 2 4 5 11 4 Victoria Beckham 5 3 7 3 5 7 5 4 7 6 5 5 6 5 Tulisa 3 4 3 9 5 3 0 4 3 1 4 1 2 11 Kelly Rowland 2 3 2 1 3 3 1 3 1 3 3 3 1 3 Angelina Jolie 2 2 1 0 4 1 1 2 1 3 1 3 0 2 Which of the following do you think has been the most stylish man of 2011? [Don't knows and none of the above's removed, N=1050] David Beckham 19 17 22 9 17 24 23 16 24 18 16 27 23 6 Gary Barlow 11 10 11 9 21 8 4 12 10 9 9 10 10 22 George Clooney 10 12 9 2 7 11 17 11 9 13 13 8 6 13 Prince William 10 11 9 8 5 7 19 9 11 7 10 11 14 4 Michael Buble 9 9 8 14 9 9 5 7 11 4 12 7 10 6 Johnny Depp 9 9 9 11 11 9 5 10 7 6 8 9 10 13 Daniel Craig 8 10 7 5 9 11 6 7 10 10 9 9 6 9 Colin Firth 7 6 8 7 5 7 12 11 3 12 7 7 6 7 Olly Murs 6 5 7 18 7 5 1 6 7 7 9 6 4 3 Hugh Laurie 4 6 3 10 3 4 3 5 3 4 4 5 4 2 Ryan Gosling 2 1 3 4 4 1 0 2 2 7 1 1 2 2 Vernon Kay 2 1 2 0 1 1 3 1 2 1 1 1 2 3 David Cameron 2 1 2 0 0 2 3 2 1 2 2 1 2 1 Robert Pattinson 1 1 1 4 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 10 1 © 2011 YouGov plc. -

British Masculinity and Propaganda During the First World War Evan M

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2015 British Masculinity and Propaganda during the First World War Evan M. Caris Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caris, Evan M., "British Masculinity and Propaganda during the First World War" (2015). LSU Master's Theses. 4047. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4047 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRITISH MASCULINITY AND PROPAGANDA DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Evan M. Caris B.A. Georgia College & State University, 2011 December 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTACT ..................................................................................................................................... iii 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 2. MASCULINITY IN BRITISH PROPAGANDA POSTERS DURING THE FIRST WORLD -

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Dr Kate McNicholas Smith, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Professor Imogen Tyler, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Abstract The last decade has witnessed a proliferation of lesbian representations in European and North American popular culture, particularly within television drama and broader celebrity culture. The abundance of ‘positive’ and ‘ordinary’ representations of lesbians is widely celebrated as signifying progress in queer struggles for social equality. Yet, as this article details, the terms of the visibility extended to lesbians within popular culture often affirms ideals of hetero-patriarchal, white femininity. Focusing on the visual and narrative registers within which lesbian romances are mediated within television drama, this article examines the emergence of what we describe as ‘the lesbian normal’. Tracking the ways in which the lesbian normal is anchored in a longer history of “the normal gay” (Warner 2000), it argues that the lesbian normal is indicative of the emergence of a broader post-feminist and post-queer popular culture, in which feminist and queer struggles are imagined as completed and belonging to the past. Post-queer popular culture is depoliticising in its effects, diminishing the critical potential of feminist and queer politics, and silencing the actually existing conditions of inequality, prejudice and stigma that continue to shape lesbian lives. Keywords: Lesbian, Television, Queer, Post-feminist, Romance, Soap-Opera Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Increasingly…. to have dignity gay people must be seen as normal (Michael Warner 2000, 52) I don't support gay marriage despite being a Conservative. -

Housing Market Takes Buyers on 'Wild'

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 FRIDAY JULY 9, 2021 DEALS OF THE Housing market takes buyers on ‘wild’ $rideDAY$ PG. 3 By Sam Minton DiVirgilio explained that ITEM STAFF this can drive the prices of surrounding homes as It might seem like a sim- well. He said that this is ple business practice, but part of the reason that the high demand and low in- housingDEALS market continues ventory can lead to prices to go up.OF THE for any particular product Schweihs works on the to increase. North Shore, in areas in- Right now this is hap- $DAY$ cluding Marblehead,PG. 3 Sa- pening to the housing lem, Saugus and Swamp- market in the area. Low scott. He said that for the inventory is leading buy- past 6-8 months it has ers to have to go in on been a “crazy” seller’s homes above the asking market and that he has price to ensure that they buyersDEALS being forced to of- even have a chance of se- fer anywhere from 10-20 curing a home. percentOF above THE the asking According to multiple price. realtors, they are seeing a Joan $Regan,DA Ywho$ works lot more cash offers take for CenturyPG. 21 3 in Lynn, place in the current mar- also described the market ket. Andrew Schweihs of only realtor who men- said. “Buyers are guaran- as “wild” in the city. Re- AJS Real Estate said that Realtors, from left, Albert DiVirgilio, Joan Re- tioned this. Albert DiVir- gan and Andrew Schweihs say it’s a seller’s teeing their offer so basi- gan mentioned that she he is even seeing buyers has seen offers between gilio from Re/Max said market right now on the North Shore. -

Will It Be Fifth Time Lucky for Steve?

INTERVIEW FOR BETTER...Kate Ford,O 34, who firstR took on the roleWORSE? very instinctive. She’ll just know when the Coronation Street’s Steve McDonald is about of Tracy 10 years ago, isn’t one to make time is right to take the ammunition out. apologies for her character’s appalling “Basically, she decides to put on a cracking to marry scheming Tracy Barlow – unless behaviour. And yet she can understand, at outfit, rock up to the church and say to Becky’s bombshell wrecks their big day least to a degree, why Tracy has resorted to Steve, ‘This is what you could have won…’” such extreme, unforgivable measures. There are several ways this could then BECKY DECIDES “She’s so scared of losing him,” she pan out, of course, particularly with vil, twisted, And how long did our sympathy last? explains. “She’s just desperate.” regard to Katherine’s final scenes. Will TO PUT ON A poisonous Ooh, several hours. By the following And Kate adds that, for all her character’s she successfully wreck the wedding? Will CRACKING OUTFIT, – over the years, episode, true to form, Tracy had turned this faults, “Tracy is a genuinely devoted mum.” she reconcile with Steve? Will she be ROCK UP TO Ewe’ve pinned terrible tragedy to her advantage in the What sets us up so nicely for Monday’s leaving alone? Or will she pledge her THE CHURCH AND no end of labels on most despicable fashion, claiming that a fall marriage ceremony is the fact that future to this Danny chap she’s taken such TRACY’S SO Coronation Street’s down the stairs at Becky McDonald’s flat Katherine Kelly, who’s been playing the a shine to – the widowed hotel manager SAY TO STEVE, SCARED OF LOSING Tracy Barlow. -

European Social History, 1830-1914 Fall 2013, Humanities 1641, TR 4-5:15 Prof

History 474: European Social History, 1830-1914 Fall 2013, Humanities 1641, TR 4-5:15 Prof. Koshar, Humanities 4101; Office hours: R 2:00-3:45 & by appt. email: [email protected] Rationale: Europe in the nineteenth century became recognizably “modern.” Factory- based manufacture increasingly shaped the economic life of men and women even though small-scale production and agriculture persisted and in some cases flourished. Urban centers grew in population and influence, becoming economic motors as well as cultural magnets. Science, technology, and more rapid means of communication exerted influence in the most intimate spaces of people’s lives. As free, compulsory education grew, literacy and cultural entertainments expanded, becoming more widely available to people of lesser means in both urban and rural milieus. New political parties mobilized larger constituencies; the masses were no longer bit players on the political stage. As modern parties became more organized and socially anchored, so too did ideologies—liberal, socialist, sectarian, nationalist, racist, or conservative—assume more importance in laying out blueprints for the future. Increasingly bureaucratized national states both responded to and facilitated such large-scale changes. Through it all, Europeans asserted themselves not only as members of families, churches, regions, and nations but also as individuals. In surveying these massive transformations, this course focuses on a single yet complex thread of European social experience: the relationship between the individual and the modern state. Goals: The pedagogical goals of the course are: to deepen your knowledge of nineteenth- century European social history in all its drama and many-sidedness; to build your expository and critical skills through writing and discussion; to advance your abilities to analyze primary sources (novels, memoirs, autobiographies) with reference to larger historical narratives and problems; and where possible to relate past and present through rigorous comparison and analogy. -

Free Deirdre Shirt

Free deirdre shirt click here to download Mens Deirdre Barlow Free The Weatherfield One T-shirt: Free UK Shipping on Orders Over £20 and Free Day Returns, on Selected Fashion Items Sold or. Ladies Deirdre Barlow Free The Weatherfield One T-shirt: Free UK Shipping on Orders Over £20 and Free Day Returns, on Selected Fashion Items Sold or. Description. FREE DEIRDRE RASHHID CORONATION STREET PARODY T SHIRT. IF YOU LIKE THIS COME AND TAKE A LOOK IN OUR FAT DAD EBAY. High quality Deirdre Barlow inspired T-Shirts by independent artists and designers from around the world. Deirdre Barlow Free the Wetherfield one T-Shirt. Buy 'Deirdre Barlow Free the Wetherfield one' by pickledjo as a T-Shirt, Classic T-Shirt, Tri-blend T-Shirt, Lightweight Hoodie, Women's Fitted Scoop T-Shirt. The jailing of Deirdre Rachid in Coronation Street has captured the public The tabloids are issuing 'Free Deirdre' stickers and T-shirts. RIP Deirdre Barlow: Corrie fans rush to snap up 'Free The Weatherfield Deirdre Barlow – soap fans have rushed to snap up a t-shirt depicting. Crinkle shirt of mixed fabrics. Stretch side panels. Home; DEIRDRE SHIRT. MULTI. Zoom Free shipping Australia Wide for orders over $ Read More. The push for her release was spearheaded by the country's tabloid newspapers, who offered stickers and t-shirts saying “Free Deirdre” and. The Coronation Street star's drama as she was thrown behind bars while her lover walked free enraged the nation. Deirdre ran her hand over Luke's ass. “Aces is taking over. She put her free hand up his shirt and pulled it up to suck on his nipple. -

Violence in UK Soaps

Violence in UK Soaps: A four wave trend analysis Dr Guy Cumberbatch, Victoria Lyne, Andrea Maguire and Sally Gauntlett July 2014 CRG UK Ltd Anvic House A report prepared for: 84 Vyse Street Ofcom Jewellery Quarter Birmingham B18 6HA t: ++(0)121 523 9595 f: ++(0)121 523 8523 e: [email protected] Contents Foreword from Ofcom .......................................................................................................................... 1 1 Violence in UK soaps: A four-wave trend analysis (2001-2013) ............................................... 2 1.1 Executive summary ................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Key findings: overall violence in soaps 2001-2013 ................................................................. 3 1.3 Key findings: changes in violent content over period 2001-2013 ........................................... 4 1.4 Key findings: 2013 storyline analysis ...................................................................................... 5 1.5 Key findings: 2013 case studies of scenes containing strong violence .................................. 5 1.6 Overall conclusions ................................................................................................................. 6 2 Objectives, methodology and sample ......................................................................................... 7 2.1 Overall objectives ...................................................................................................................