PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070)--Speeches/Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One Man's Personal Campaign to Save the Building – Page 8

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online Goodbye TVC One man’s personal campaign to save the building – page 8 April 2013 • Issue 2 bbC expenses regional dance band down television drama memories Page 2 Page 6 Page 7 NEWS • MEMoriES • ClaSSifiEdS • Your lEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 baCk at thE bbC Pollard Review findings On 22 February, acting director general Tim Davie sent the following email to all staff, in advance of the publication of the Nick Pollard. Pollard Review evidence: hen the Pollard Review was made clearer to ensure all entries meet BBC published back in December, Editorial standards. we said that we would The additional papers we’ve published Club gives tVC a great release all the evidence that today don’t add to Nick Pollard’s findings, send off WNick Pollard provided to us when he they explain the factual basis of how he (where a genuine and identifiable interest of delivered his report. Today we are publishing arrived at them. We’ve already accepted the BBC is at stake). Thank you to all the retired members and all the emails and documents that were the review in full and today’s publication There will inevitably be press interest and ex-staff who joined us for our ‘Goodbye to appended to the report together with the gives us no reason to revisit that decision as you would expect we’re offering support to TVC’ on 9 March. The day started with a transcripts of interviews given to the review. or the actions we are already taking. -

Between L.S. Lowry and Coronation Street: Salford Cultural Identities

Between L.S. Lowry and Coronation Street: Salford Cultural Identities Susanne Schmid Abstract: Salford, “the classic slum”, according to Robert Roberts’s study, has had a distinct cultural identity of its own, which is centred on the communal ideal of work- ing-class solidarity, best exemplified in the geographical space of “our street”. In the wake of de-industrialisation, Roberts’s study, lyrics by Ewan MacColl, L.S. Lowry’s paintings, and the soap opera Coronation Street all nostalgically celebrate imagined northern working-class communities, imbued with solidarity and human warmth. Thereby they contribute to constructing both English and northern identities. Key names and concepts: Friedrich Engels - Robert Roberts - Ewan MacColl - L.S. Lowry - Charles Dickens - Richard Hoggart - George Orwell; Slums - Escaper Fiction - Working-class Culture - Nostalgia - De-industrialisation - Rambling - Coronation Street. 1. Salford as an Imagined Northern Community For a long time, Salford, situated right next to the heart of Manchester, has been known as a place that underwent rapid and painful industri- alisation in the nineteenth century and an equally difficult and agonis- ing process of de-industrialisation in the twentieth. If Manchester, the former flag-ship of the cotton industry, has been renowned for its beautiful industrial architecture, its museums, and its economic suc- cess, Salford has been hailed as “the classic slum”, as in the title of Robert Roberts’s seminal study about Salford slum life in the first quarter of the twentieth century (Roberts 1990, first published in 1971). The equation of “Salford” and “slum”, however, dates back further than that. Friedrich Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England, written in 1844/45, casts a gloomy light on a city made up of dwellings hardly fit for humans: 348 Susanne Schmid If we cross the Irwell to Salford, we find on a peninsula formed by the river, a town of eighty thousand inhabitants […]. -

The Production of Religious Broadcasting: the Case of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository The Production of Religious Broadcasting: The Case of the BBC Caitriona Noonan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Cultural Policy Research Department of Theatre, Film and Television University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ December 2008 © Caitriona Noonan, 2008 Abstract This thesis examines the way in which media professionals negotiate the occupational challenges related to television and radio production. It has used the subject of religion and its treatment within the BBC as a microcosm to unpack some of the dilemmas of contemporary broadcasting. In recent years religious programmes have evolved in both form and content leading to what some observers claim is a “renaissance” in religious broadcasting. However, any claims of a renaissance have to be balanced against the complex institutional and commercial constraints that challenge its long-term viability. This research finds that despite the BBC’s public commitment to covering a religious brief, producers in this style of programming are subject to many of the same competitive forces as those in other areas of production. Furthermore those producers who work in-house within the BBC’s Department of Religion and Ethics believe that in practice they are being increasingly undermined through the internal culture of the Corporation and the strategic decisions it has adopted. This is not an intentional snub by the BBC but a product of the pressure the Corporation finds itself under in an increasingly competitive broadcasting ecology, hence the removal of the protection once afforded to both the department and the output. -

The Evolution of British Asian Radio in England: 1960 – 2004

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bournemouth University Research Online The Evolution of British Asian Radio in England: 1960 – 2004 Gloria Khamkar Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2016 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. II ABSTRACT Title: The Evolution of British Asian Radio in England: 1960 – 2004 Author: Gloria Khamkar This doctoral research examines the evolution of British Asian radio in England from 1960 to 2004. During the post-war period an Asian community started migrating to Britain to seek employment as a result of the industrial labour shortage. The BBC and the independent local radio sector tried to cater to this newly arrived migrant community through its radio output either in their mother tongue or in the English language. Later, this Asian community started its own separate radio services. This research project explores this transformation of Asian radio, from broadcasting radio programmes for the Asian community on existing radio stations, to the creation of independent local and community radio stations, catering to the Asian community exclusively in England. Existing research concentrates on the stereotype images and lack of representation of Asian community on the British radio; it lacks a comprehensive overview of the role of radio during the settlement period of the newly migrant Asian community. -

Trick Film: Neil Brand's Radio Dramas and the Silent Film Experience

Trick film: Neil Brand’s radio dramas and the silent film experience McMurtry, LG http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/iscc.10.1-2.1_1 Title Trick film: Neil Brand’s radio dramas and the silent film experience Authors McMurtry, LG Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/51763/ Published Date 2019 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Trick Film: Neil Brand’s Radio Dramas and the Silent Film Experience Leslie McMurtry, University of Salford Abstract At first glance, silent film and audio drama may appear antithetical modes of expression. Nevertheless, an interesting tradition of silent film-to-radio adaptations has emerged on BBC Radio Drama. Beyond this link between silent film and radio drama, other radio dramas have highlighted that Neil Brand, a successful silent film accompanist, radio dramatist, and composer, links the silent film experience and audio drama in two of his plays, Joanna (2002) and Waves Breaking on a Shore (2011). Using theories of sound and narrative in film and radio, as well as discussing the way radio in particular can stimulate the generation of imagery, this article examines layered points of view/audition as ways of linking the silent film experience and the use of sound within radio drama. -

Coronation Street Jailbirds

THIS WEEK Coronation Street’s Maria Connor is released from prison this week J – and ex-lover Aidan should beware, says actress Samia Longchambon CORONATION STREET AILBIRDS Maria Connor is by no means the first he view from Maria Connor’s window is by him? After all, it was only a couple of weeks almost tear-jerkingly romantic. It’s ago that her cellmate was remarking, a little Weatherfield woman to end up behind bars… Christmas Eve 2016 and, as if on cue, CORONATION ominously, “Men, eh? Can’t live with ’em, can’t plump white snowflakes have begun to STREET, smash ’em in the head with an iron bar…” DEIRDRE RACHID 1998 T Wrongly convicted of fraud after flutter gently to the ground. Could she have MONDAY, ITV “She does love Aidan,” says Samia. “It wished to gaze out on a more festive scene? hasn’t just been a sexual thing. He’s been her being set up by her fiancé, conman Well, yes, she could. For one thing, she knight in shining armour, her hero.” Jon Lindsay. The injustice sparked a could have wished for the window not to have And yes, he was certainly a tower of strength real-life Free The Weatherfield One campaign. Prime Minister Tony Blair thick iron bars across it. when an innocent Maria found herself falsely even raised it in Parliament. Yes, this was the night a frightened, despairing Maria accused of murder, back in November. But when it began a 12-month prison sentence for an illegal came to the day of her sentencing for this crazy HAYLEY CROPPER marriage, joining a long and illustrious line of marriage scam, for which she pleaded guilty, (NÉE PATTERSON) 2001 Coronation Street women who, over the years, have Aidan tarnished his image by failing to show. -

Survey Report

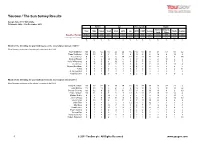

YouGov / The Sun Survey Results Sample Size: 1767 GB Adults Fieldwork: 20th - 21st December 2011 Gender Age Social grade Region Rest of Midlands / Total Male Female 18-24 25-39 40-59 60+ ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland South Wales Weighted Sample 1767 859 908 214 451 604 498 1007 760 226 574 378 435 154 Unweighted Sample 1767 837 930 68 509 706 484 1154 613 180 632 374 418 163 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Which of the following do you think has been the most stylish woman of 2011? [Don't knows and none of the above's removed, N=1203] Kate Middleton 50 46 54 50 42 44 65 50 50 56 48 53 50 42 Pippa Middleton 10 15 5 4 11 11 9 10 9 5 12 9 10 8 Helen Mirren 9 6 12 3 5 14 12 9 10 11 12 6 8 14 Emma Watson 7 9 6 14 10 6 3 9 5 6 8 10 5 6 Holly Willoughby 6 6 5 3 10 6 3 5 7 6 5 5 7 7 Cheryl Cole 5 7 4 14 5 5 2 4 7 2 4 5 11 4 Victoria Beckham 5 3 7 3 5 7 5 4 7 6 5 5 6 5 Tulisa 3 4 3 9 5 3 0 4 3 1 4 1 2 11 Kelly Rowland 2 3 2 1 3 3 1 3 1 3 3 3 1 3 Angelina Jolie 2 2 1 0 4 1 1 2 1 3 1 3 0 2 Which of the following do you think has been the most stylish man of 2011? [Don't knows and none of the above's removed, N=1050] David Beckham 19 17 22 9 17 24 23 16 24 18 16 27 23 6 Gary Barlow 11 10 11 9 21 8 4 12 10 9 9 10 10 22 George Clooney 10 12 9 2 7 11 17 11 9 13 13 8 6 13 Prince William 10 11 9 8 5 7 19 9 11 7 10 11 14 4 Michael Buble 9 9 8 14 9 9 5 7 11 4 12 7 10 6 Johnny Depp 9 9 9 11 11 9 5 10 7 6 8 9 10 13 Daniel Craig 8 10 7 5 9 11 6 7 10 10 9 9 6 9 Colin Firth 7 6 8 7 5 7 12 11 3 12 7 7 6 7 Olly Murs 6 5 7 18 7 5 1 6 7 7 9 6 4 3 Hugh Laurie 4 6 3 10 3 4 3 5 3 4 4 5 4 2 Ryan Gosling 2 1 3 4 4 1 0 2 2 7 1 1 2 2 Vernon Kay 2 1 2 0 1 1 3 1 2 1 1 1 2 3 David Cameron 2 1 2 0 0 2 3 2 1 2 2 1 2 1 Robert Pattinson 1 1 1 4 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 10 1 © 2011 YouGov plc. -

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Dr Kate McNicholas Smith, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Professor Imogen Tyler, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Abstract The last decade has witnessed a proliferation of lesbian representations in European and North American popular culture, particularly within television drama and broader celebrity culture. The abundance of ‘positive’ and ‘ordinary’ representations of lesbians is widely celebrated as signifying progress in queer struggles for social equality. Yet, as this article details, the terms of the visibility extended to lesbians within popular culture often affirms ideals of hetero-patriarchal, white femininity. Focusing on the visual and narrative registers within which lesbian romances are mediated within television drama, this article examines the emergence of what we describe as ‘the lesbian normal’. Tracking the ways in which the lesbian normal is anchored in a longer history of “the normal gay” (Warner 2000), it argues that the lesbian normal is indicative of the emergence of a broader post-feminist and post-queer popular culture, in which feminist and queer struggles are imagined as completed and belonging to the past. Post-queer popular culture is depoliticising in its effects, diminishing the critical potential of feminist and queer politics, and silencing the actually existing conditions of inequality, prejudice and stigma that continue to shape lesbian lives. Keywords: Lesbian, Television, Queer, Post-feminist, Romance, Soap-Opera Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Increasingly…. to have dignity gay people must be seen as normal (Michael Warner 2000, 52) I don't support gay marriage despite being a Conservative. -

Media Nations 2020 UK Report

Media Nations 2020 UK report Published 5 August 2020 Contents Section Overview 3 1. Covid-19 media trends: consumer behaviour 6 2. Covid-19 media trends: industry impact and response 44 3. Production trends 78 4. Advertising trends 90 2 Media Nations 2020 Overview This is Ofcom’s third annual Media Nations, a research report for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. It reviews key trends in the TV and online video sectors, as well as radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this report is an interactive report that includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. This year’s publication comes during a particularly eventful and challenging period for the UK media industry. The Covid-19 pandemic and the ensuing lockdown period has changed consumer behaviour significantly and caused disruption across broadcasting, production, advertising and other related sectors. Our report focuses in large part on these recent developments and their implications for the future. It sets them against the backdrop of longer-term trends, as laid out in our five-year review of public service broadcasting (PSB) published in February, part of our Small Screen: Big Debate review of public service media. Media Nations provides further evidence to inform this, as well as assessing the broader industry landscape. We have therefore dedicated two chapters of this report to analysis of Covid-19 media trends, and two chapters to wider market dynamics in key areas that are shaping the industry: • The consumer behaviour chapter examines the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on media consumption trends across television and online video, and radio and online audio. -

Housing Market Takes Buyers on 'Wild'

DEALS OF THE $DAY$ PG. 3 FRIDAY JULY 9, 2021 DEALS OF THE Housing market takes buyers on ‘wild’ $rideDAY$ PG. 3 By Sam Minton DiVirgilio explained that ITEM STAFF this can drive the prices of surrounding homes as It might seem like a sim- well. He said that this is ple business practice, but part of the reason that the high demand and low in- housingDEALS market continues ventory can lead to prices to go up.OF THE for any particular product Schweihs works on the to increase. North Shore, in areas in- Right now this is hap- $DAY$ cluding Marblehead,PG. 3 Sa- pening to the housing lem, Saugus and Swamp- market in the area. Low scott. He said that for the inventory is leading buy- past 6-8 months it has ers to have to go in on been a “crazy” seller’s homes above the asking market and that he has price to ensure that they buyersDEALS being forced to of- even have a chance of se- fer anywhere from 10-20 curing a home. percentOF above THE the asking According to multiple price. realtors, they are seeing a Joan $Regan,DA Ywho$ works lot more cash offers take for CenturyPG. 21 3 in Lynn, place in the current mar- also described the market ket. Andrew Schweihs of only realtor who men- said. “Buyers are guaran- as “wild” in the city. Re- AJS Real Estate said that Realtors, from left, Albert DiVirgilio, Joan Re- tioned this. Albert DiVir- gan and Andrew Schweihs say it’s a seller’s teeing their offer so basi- gan mentioned that she he is even seeing buyers has seen offers between gilio from Re/Max said market right now on the North Shore. -

MORE to DO! Family

NEWSLETTER DECEMBER 2019 web: www.bbcpa.org.uk e: [email protected] hristmas is a season of celebration, rebirth, Crecollection, colour and joy. We remember too, days of our childhood and absent friends and MORE TO DO! family. It is an ending of old resolutions and new ones to think about with the start of the New Year. he BBC Pensioners’ a hard act to follow. I’m TAssociation has been sure, that all our members, A 16 PAGE looking at what we offer to myself included, wish him you, the members, and how well and thank him for a ISSUE! we can do even more. major contribution to the PAGE 1 way the BBCPA is run. This next year our aim is At the AGM in April Alan Seasons Greetings to make all members enjoy Bilyard also stepped down. New Members the sense of community we Alan has generously agreed PAGE 2 felt whilst working at the to stand in until we find Membership Sec. BBC. With this new way of a volunteer to take over Notes. thinking, with the increased the reins. These two roles Treasurer’s Notes deals and website, Mail- are vital to maintaining chimp and publications, the the standards we have set PAGE 3 BBC Pensioners Association ourselves as a Committee. BBC Pension Scheme now offers even more Needless to say, we are Report value for a relatively small looking for volunteers to PAGE 4 membership fee. fill these roles and help us continue to offer a first Regional Meetings With increased membership class service to members. -

Access Services Research

ACCESS SERVICES RESEARCH Ofcom - the body responsible for regulating TV programmes - has asked MORI to conduct an important study on access services. Access services include subtitling, signing and audio description, and are intended to help people with hearing and /or visual impairments to better enjoy and understand TV programmes. We are keen to find out your views and would very much appreciate it if you could spare 15 minutes or so to complete this questionnaire. Your opinions will make a difference - by contributing to the survey you will have an opportunity to influence future policy in this area. The information that you provide will be treated in the strictest confidence by MORI, the market research company. The survey is entirely anonymous, and your answers will never be linked to you as an individual. Thank you in advance for your help, and we very much look forward to receiving your views. WHEN YOU HAVE FINISHED THIS QUESTIONNAIRE PLEASE RETURN IT TO THE MORI INTERVIEWER. THEY WILL ALSO BE ABLE TO HELP YOU COMPLETE THE SURVEY, SHOULD YOU NEED ASSISTANCE. About You In which part of Great Britain do you live? a PLEASE TICK ONE BOX ONLY North East ...................................................................... Wales.............................................................................. North West ..................................................................... Scotland ......................................................................... South West....................................................................