Frauenkirchen Mania the Frauenkirche, 'Dresden Cathedral'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wonders of Germany & Austria

WONDERS OF GERMANY & AUSTRIA with Oberammergau 2020 7 May 2020 15 Days from $5,499 This tour takes advantage of the European spring season, with the beauty and mild weather. There’ll be plenty of time to enjoy some of the great German-speaking cities of central Europe – Berlin, Dresden and Vienna; experiencing the life, culture, religion and history of these cities. Archdeacon John Davis leads this tour, his second time to Oberammergau. He is the former Vicar General of the Anglican Diocese of Wangarattta. John has led several groups to Assisi, as well as to Oberammergau. Archdeacon John Davis Tour INCLUSIONS • 12 nights’ accommodation at 4 star hotels as listed • Oberammergau package including 1 nights (or similar) with breakfast daily accommodation, category 2 ticket and dinner • 5 dinners in hotels; 3 dinners in local restaurants • Services of a professional English-speaking Travel • Lunch at the Hofbrahaus Director throughout. Local expert guides where required & as noted on the itinerary • Sightseeing and entrance fees as outlined in the itinerary • Tips to Travel Director and Driver • Luxury air-conditioned coach with panoramic • Archdeacon John Davis as your host windows myselah.com.au 1300 230 271 ITINERARY Summarised Friday 8 May Saturday 16 May BERLIN OBERAMMERGAU Free day to explore. Drive to Oberammergau (travel time approx. 90 mins). Spend some free time in the quaint village Saturday 9 May before the Passion Play performance beings BERLIN at 2.30pm. There is a dinner break followed Today we will visit the two cathedrals in the Mitte by the second half of the play, concluding at area (Berlin Cathedral and St Hedwig’s) before an approximately 10.30pm. -

Augustus II the Strong's Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches

Augustus II the Strong’s Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches Palais zu Dresden: A Visual Demonstration of Power and Splendor Zifeng Zhao Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal September 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Zifeng Zhao 2018 i Abstract In this thesis, I examine Augustus II the Strong’s porcelain collection in the Japanisches Palais, an 18th-century Dresden palace that housed porcelains collected from China and Japan together with works made in his own Meissen manufactory. I argue that the ruler intended to create a social and ceremonial space in the chinoiserie style palace, where he used a systematic arrangement of the porcelains to demonstrate his kingly power as the new ruler of Saxony and Poland. I claim that such arrangement, through which porcelains were organized according to their colors and styles, provided Augustus II’s guests with a designated ceremonial experience that played a significant role in the demonstration of the King’s political and financial prowess. By applying Gérard de Lairesse’s color theory and Samuel Wittwer’s theory of “the phenomenon of sheen” to my analysis of the arrangement, I examine the ceremonial functions of such experience. In doing so, I explore the three unique features of porcelain’s materiality—two- layeredness, translucency and sheen. To conclude, I argue that the secrecy of the technology of porcelain’s production was the key factor that enabled Augustus II’s demonstration of power. À travers cette thèse, j'examine la collection de porcelaines d'Auguste II « le Fort » au Palais Japonais, un palais à Dresde du 18ème siècle qui abritait des porcelaines provenant de Chine, du Japon et de sa propre manufacture à Meissen. -

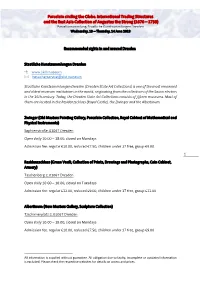

Porcelain Circling the Globe. International Trading Structures And

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of twelve museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

Bach's Organ World Tour of Germany

Bach’s Organ World Tour of Germany for Organists & Friends June 2 - 11, 2020 (10 days, 8 nights) There will be masterclasses and opportunity for organists to play many of the organs visited. Non- organists are welcome to hear about/listen to the organs or explore the tour cities in more depth Day 1 - Tuesday, June 2 Departure Overnight flights to Berlin, Germany (own arrangements or request from Concept Tours). Day 2 - Wednesday, June 3 Arrival/Dresden Guten Tag and welcome to Berlin! (Arrival time to meet for group transfer tbd.) Meet your English-speaking German tour escort who’ll be with you throughout the tour. Board your private bus for transfer south to Dresden, a Kunststadt (City of Art) along the graceful Elbe River. Dresden’s glorious architecture was reconstructed in advance of the city’s 800th anniversary. Highlights include the elegant Zwinger Palace and the baroque Hofkirche (Court Church). Check in to hotel for 2 nights. Welcome dinner and overnight. Day 3 - Thursday, June 4 Dresden This morning enjoy a guided walking tour of Dresden. Some of the major sights you'll see: the Frauenkirche; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Painting Gallery of Old Masters); inside the Zwinger; the majestic Semper Opera House; Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vaults); the Brühlsche Terrasse overlooking the River Elbe. Free time afterwards for your own explorations. 3pm Meet at the Kreuzkirche to attend the organ recital “Orgel Punkt 3”. Visit Hofkirche and have a resident organist (tbc) demonstrate the Silbermann organ, followed by some organ time for members. Day 4 - Friday, June 5 Freiberg/Pomssen/Leipzig After breakfast, check out, board bus and depart. -

Theatrum Historiae 24 (2019)

Ústav historických věd Fakulta filozofická Univerzita Pardubice Theatrum historiae 24 2019 Pardubice 2019 Na obálku byla použita část obrazu Bernarda Bellotta Pohled na Drážďany z pravého přehu Labe nad Augustovým mostem, cca 1750 – 1755, olej na plátně, 52 x 82 cm ze sbírek Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie (Wikimedia Commons), dostupný na: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bellotto_View_of_Dresden.jpg © Univerzita Pardubice, 2019 evidenční číslo MK ČR E 19534 ISSN 1802–2502 Obsah Michal TÉRA Korutanský nastolovací obřad a přemyslovský mýtus 9 Urszula KICIŃSKA Political activity of widows as an example of shaping cliental dependencies in the second half of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries 41 Bożena POPIOŁEK Patrons and clients. The specificity of female clientelism in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth at the turn of the seventeenth century. Research postulates 55 Agnieszka SŁABY Emotional pressure and violence in the milieu of the nobility in the Saxon era of the Polish-Lithuaninan Commonwealth 71 Iveta COUFALOVÁ Jan Nepomucký v luteránských Drážďanech. Rekonverze Wettinů a role českého zemského patrona v 1. polovině 18. století 89 Filip VÁVRA Rezidenční síť Františka Josefa Černína z Chudenic ve Vídni a v Praze ve 20. a 30. letech 18. století 109 PETR WOHLMUTH Poručík proti maršálovi. Dvojí výzva post-vaubanovské tradici v textech skotského vojenského inženýra Charlese Bisseta z let 1751–1778 137 GABRIELA KREJČOVÁ ZAVADILOVÁ Pokusy o vzdělávání prvních českých kazatelů augsburského vyznání 173 PETER DEMETER – DANA MAREŠOVÁ Životní cesta Terezie Dalbergové (1866–1893) za uzdravením. Zbožná pouť do francouzských Lurd 191 Dana MUSILOVÁ – Pavla PLACHÁ Ženská nucená práce v českých zemích 1939–1945 205 Recenze a zprávy 223 Seznam recenzentů 241 Seznam autorů 242 9 Michal TÉRA Korutanský nastolovací obřad a přemyslovský mýtus Abstract: Carinthian Enthronization Ceremony and the Premyslid Myth The present study deals with the medieval enthronization ceremony held in Zollfeld near Karnburg where the Carinthian dukes were inaugurated. -

Dresden Cathedral

Zelenka · Hasse Sacred Music for Dresden Cathedral Jan Dismas Zelenka Accademia Barocca Lucernensis Johann Adolph Hasse Choir Gunhild Alsvik, Marianne Knoblauch, Eva Maria Soler Boix soprano Sacred Music at Alberto Miguélez Rouco, Susanne Andres, Désirée Mori alto Remy Burnens, Raphaël Bortolotti, Christopher Wattam tenor Alexandre Beuchat, Jonas Atwood, Álvaro Etcheverry bass Dresden Cathedral Orchestra Lathika Vithanage (concert master), Natalie Carducci, Rahel Wittling, Lukas Hamberger violin I Marta Ramírez, Paula Pérez, Elena Abbati violin II Matthias Jäggi, Sara Gómez Yunta viola Bettina Simon, Bénédicte Wodeyoboe Gunhild Alsvik, Eva Maria Soler Boix soprano Alberto Miguélez Rouco alto Basso continuo Remy Burnens tenor Simon Linné lute Alexandre Beuchat bass Andrew Burn bassoon Carla Rovirosa violoncello Elisabeth Forster Büttner violone Accademia Barocca Lucernensis Andreas Westermann organ Javier Ulises Illán direction Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679-1745) Miserere ZWV 57 (1738) 1 Miserere I 2:05 2 Miserere II 4:14 3 Gloria Patri I 3:58 4 Gloria Patri II 0:39 5 Sicut erat et Miserere III 2:36 Confitebor tibi ZWV 71 (1729) 6 Confitebor tibi Domine 3:41 7 Memoriam fecit 6:40 Johann Adolph Hasse (1699-1783) Miserere (Dresden version for mixed choir, after 1733) 8 Miserere mei Deus 3:43 9 Tibi soli peccavi 1:27 10 Ecce enim 6:19 11 Libera me 3:58 12 Quoniam si voluisses 2:04 13 Benigne fac 1:16 14 Gloria Patri 2:51 15 Sicut erat - Amen 1:11 Accademia Barocca Lucernensis in concert Matthäuskirche, Luzern 2018 16 Confitebor tibi (1737-1756?) 5:15 Von Verkennung, Prestige und großer Wirkung Die Musikpflege in Dresden war im 18. -

Dresden. Die Beste Entscheidung. the Best Decision. #DRESDEN

Dresden. Die beste Entscheidung. The best decision. #DRESDEN 2 3 01 Wallpavillon im Dresdner Zwinger | Wallpavillon at Dresden’s Zwinger 1728 war der Dresdner Zwinger im Wesentlichen fertiggestellt. Diente er einst als Orangerie und Festkulisse, beherbergt er heute die Kunstschätze mehrerer Museen. was the year most of Dresden’s Zwinger was completed. Originally used as an orangery and a venue for festivities, it today houses several museums’ artistic treasures. 1697 wurde Kurfürst Friedrich August I. von Sachsen, bekannt auch als „August der Starke“, zum König von Polen gewählt. was the year Augustus II the Strong, also known as Elector Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, was elected Prächtig King of Poland. Magnificent DRESDEN.DE/STADTPORTRAIT 4 5 Prächtig Hervorragende Künstler aus ganz Europa wirkten am „Gesamtkunstwerk Dresden“ Glanzvoll wiedererstanden mit. Neben genialen deutschen Baumeistern prägten vor allem Italiener und Magnificent Franzosen das Bild der Stadt. So entstanden die bezaubernde FestArchitektur Gloriously resurrected des Zwingers mit ihrem perfekten Zusammenspiel von Bauform und Skulptur, die italienischen Geist atmende Katholische Hofkirche und die weltbekannte Nach der spektakulären Rekonstruktion der Dresdner Frauenkirche Frauenkirche mit ihrer steinernen Kuppel. Der malerische „Canalettoblick“ auf die mit originalen Teilen entstand auch ihr Umfeld – die Straßen züge berühmte Dresdner Silhouette wurde zum Inbegriff einer schönen Stadtansicht. rund um den Neumarkt mit Bürger und Adelshäusern des 17. bis 19. Jahrhunderts – in alter Schönheit neu. Prominent artists from all over Europe had a hand in crafting the “total work of Following the spectacular reconstruction of Dresden’s Frauenkirche art that is Dresden”; in addition to brilliant German master builders, the city’s using original parts, the area surrounding it – the streets around townscape was particularly shaped by the Italians and French. -

May 09 Pp. 23-25.Indd

Kristian Wegscheider: Master Restorer and Organbuilder Joel H. Kuznik ention Saxony to most organists, Expansion Mand they immediately think of the By 1993 it was clear that the company 18th century, Gottfried Silbermann and needed new, larger facilities. The com- his catalogue of 31 extraordinary instru- pany had expanded to ten employees, ments, which are still being played.1 with only 400 square meters of workspace An amazing testimony! But today one and with insuffi cient height to assemble hears more and more of Kristian Weg- instruments. Finally a carpenter’s work- scheider, widely admired for his dynamic shop was found in Dresden–Hellerau in restorations of Silbermann organs as the old village center of Rähnitz. During well as those of Hildebrandt, Schnitger the move, the fi rm continued to work on a and Ladegast—and whose reputation restoration of the Silbermann for the Bre- as a builder is so respected that he was men Cathedral (I/8, 1734)8 and an identi- considered for the new organs at St. cal copy of it for the Silbermann Museum Thomas, Leipzig and the Frauenkirche in Frauenstein, so that the dedication of in Dresden. the new workshop in July 1994 could take Steven Dieck, president of C. B. Fisk, place in a concert using both organs with Inc., credits Wegscheider with being the Dresden Baroque Orchestra. “very helpful in discovering the ‘secrets’ After all this excitement, work con- of Gottfried Silbermann and continues to tinued routinely, but always with inter- be, not only for us, but also for any other esting projects. -

Report Back on Conference Seminar

5 1234567 Public report REPORT BACK ON CONFERENCE/SEMINAR REPORT TO: Scrutiny Co-ordination Committee REPORT OF: Lord Mayor of the City of Coventry 2011/12 Councillor Keiran Mulhall TITLE: Civic Visit to Dresden DATE: 9th – 11th November 2011 VENUE: Dresden, Germany Recommendation 1.1 The Scrutiny Co-ordination Committee is recommended to endorse the report of the Lord Mayor's civic visit to Dresden and the positive outcomes of the visit. 2. Background 2.1 I was invited to attend an Exhibition called “Under Attack-London, Coventry, Dresden” which the previous Lord Mayor, Brian Kelsey attended at the London Transport Museum in September 2010. I was invited by the Oberburgermeisterin (Mayor) Ms Helma Orosz and her Deputy Mayor, Mr Dirk Hilbert to represent the City of Coventry at the opening of the exhibition. 2.2 The link between the two cities is based on civic links of the two administrations and relationships between the Frauenkirche (Dresden Cathedral) and Coventry Cathedral. 2009 saw the 50th anniversary of this relationship. The presence of a Civic Representative from our City would only enhance Coventry’s image at the Exhibition as it will eventually be displayed in Coventry. 2.3 It was most regrettable that Mayor Helma Orosz, Mayor of Dresden had been taken ill and was in hospital. A number of her Deputies represented her at the official events during our visit. 3. Cost of attending Costs Approved by Total of Actual Costs Cabinet/Cabinet Member Conference Fees Nil Nil Flights £320 £392.38 Additional Travel Expenses £35 Travel Insurance £32.68 Travel Insurance Accommodation Nil Nil Subsistence Unquantified £184.09 (NOTE: IF TOTALS ARE SIGNIFICANTLY DIFFERENT PLEASE EXPLAIN WHY.) 4. -

Dresden Christ Superstar a Farce in Five Acts

ABOLISHABOLISH COMMEMORATIONCOMMEMORATION CRITIQUEA CRITIQUE TO THE OF DISCOURSE RELATING TO THE BOMBING OF DRESDEN IN 1945 Andrea Hübler Dresden Christ Superstar A Farce in five acts It was in October 2009 that the idea of a Pathway of Remembrance for Dresden was first proposed to the Lady Mayor. At a podium discussion a month later the concept was laid out in detail before a well-di- sposed audience. On the 13 February 2010, the day that marked the 65th anniversary of the bombing of Dresden, a walk along the Pathway of Remembrance was held for the first time. The initiators, trumpet virtuoso Ludwig Güttler and his companions, had great expectations for the walk. It was intended to play a ‘role that profoundly deepened the knowledge and reinforced the identi- ty of Dresden and the Dresdeners’... The objective was a walk along a route that allowed people to ‘share the experience of authentic locations at which authentic writings and contemporary witness testimony would be heard’. This, they intended, would provide a ‘contribution to remembering – against forget- ting – the 13 February 1945, that fateful day in Dresden’s history’.1 Of course the centre of attention was to be the Dresdeners’ suffering on that fateful day but also how it was overcome and not forgetting that the efforts of the inhabitants to reconstruct the city had to be properly acknowledged too. Ultimately the commemoration was to serve the future, to help open wounds to heal, leaving nothing behind but heroically scared tissue. If anyone, Ludwig Güttler was the one to know about these things. -

Madame Schumann-Heink: a Legend in Her Time

MADAME SCHUMANN-HEINK: A LEGEND IN HER TIME by Richard W. Amero Madame Ernestine Schumann-Heink's life had the before-and-after quality of a fairy story. Born in poverty, she became rich. Considered plain and plump in appearance, on stage she was regal and impressive. When she began singing in public, at age 15, no one thought she would become a professional singer. When she moved to San Diego, at age 48, music critics in Europe and the United States hailed her as "the world's outstanding contralto." Her parents called her "Tini" and her friends in Germany "Topsy," in reference to her physical size. Her children knew her by the intimate name "Nona." Composer Richard Strauss referred to her by the impersonal "the Heink," while impresario Maurice Grau addressed her by the friendlier name of "Heinke." Those who knew her on the stage or by reputation called her "Mother" or "Madame," reflecting the respect she inspired. Born Ernestine Roessler at Lieben, near Prague (then part of Austria), June 15, 1861, her mother was Italian-born Charlotte (Goldman) Roessler and her father Hans Roessler, a cavalry lieutenant in the Austrian army. She got her aggressiveness and stubbornness from her father, whom she described as "a real old roughneck." Her softer qualities and appreciation for art came from her mother, who taught her to sing "When I was three," she recalled, "I already sang. I sang what my mother sang. I'd put my mother's apron around me and start to act and sing." Ernestine became acquainted with Leah Kohn, her Jewish grandmother on her mother's side, when she was five years old.