Madame Schumann-Heink: a Legend in Her Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser, C, 2018.Pdf

The PIT: A YA Response to Miltonic Ideas of the Fall in Romantic Literature Callum Fraser Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Department of English Language, Literature and Linguistics Newcastle University i ii Abstract This project consists of a Young Adult novel — The PIT — and an accompanying critical component, titled Miltonic Ideas of the Fall in Romantic Literature. The novel follows the story of a teenage boy, Jack, a naturally talented artist struggling to understand his place in a dystopian future society that only values ‘productive’ work and regards art as worthless. Throughout the novel, we see Jack undergo a ‘coming of age’, where he moves from being an essentially passive character to one empowered with a sense of courage and a clearer sense of his own identity. Throughout this process we see him re-evaluate his understanding of friendship, love, and loyalty to authority. The critical component of the thesis explores the influence of John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, on a range of Romantic writers. Specifically, the critical work examines the way in which these Romantic writers use the Fall, and the notion of ‘falleness’ — as envisioned in Paradise Lost — as a model for writing about their roles as poets/writers in periods of political turmoil, such as the aftermath of the French Revolution, and the cultural transition between what we now regard as the Romantic and Victorian periods. The thesis’s ‘bridging chapter’ explores the connection between these two components. It discusses how the conflicted poet figures and divided narratives discussed in the critical component provide a model for my own novel’s exploration of adolescent growth within a society that seeks to restrict imaginative freedom. -

Wonders of Germany & Austria

WONDERS OF GERMANY & AUSTRIA with Oberammergau 2020 7 May 2020 15 Days from $5,499 This tour takes advantage of the European spring season, with the beauty and mild weather. There’ll be plenty of time to enjoy some of the great German-speaking cities of central Europe – Berlin, Dresden and Vienna; experiencing the life, culture, religion and history of these cities. Archdeacon John Davis leads this tour, his second time to Oberammergau. He is the former Vicar General of the Anglican Diocese of Wangarattta. John has led several groups to Assisi, as well as to Oberammergau. Archdeacon John Davis Tour INCLUSIONS • 12 nights’ accommodation at 4 star hotels as listed • Oberammergau package including 1 nights (or similar) with breakfast daily accommodation, category 2 ticket and dinner • 5 dinners in hotels; 3 dinners in local restaurants • Services of a professional English-speaking Travel • Lunch at the Hofbrahaus Director throughout. Local expert guides where required & as noted on the itinerary • Sightseeing and entrance fees as outlined in the itinerary • Tips to Travel Director and Driver • Luxury air-conditioned coach with panoramic • Archdeacon John Davis as your host windows myselah.com.au 1300 230 271 ITINERARY Summarised Friday 8 May Saturday 16 May BERLIN OBERAMMERGAU Free day to explore. Drive to Oberammergau (travel time approx. 90 mins). Spend some free time in the quaint village Saturday 9 May before the Passion Play performance beings BERLIN at 2.30pm. There is a dinner break followed Today we will visit the two cathedrals in the Mitte by the second half of the play, concluding at area (Berlin Cathedral and St Hedwig’s) before an approximately 10.30pm. -

Augustus II the Strong's Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches

Augustus II the Strong’s Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches Palais zu Dresden: A Visual Demonstration of Power and Splendor Zifeng Zhao Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal September 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Zifeng Zhao 2018 i Abstract In this thesis, I examine Augustus II the Strong’s porcelain collection in the Japanisches Palais, an 18th-century Dresden palace that housed porcelains collected from China and Japan together with works made in his own Meissen manufactory. I argue that the ruler intended to create a social and ceremonial space in the chinoiserie style palace, where he used a systematic arrangement of the porcelains to demonstrate his kingly power as the new ruler of Saxony and Poland. I claim that such arrangement, through which porcelains were organized according to their colors and styles, provided Augustus II’s guests with a designated ceremonial experience that played a significant role in the demonstration of the King’s political and financial prowess. By applying Gérard de Lairesse’s color theory and Samuel Wittwer’s theory of “the phenomenon of sheen” to my analysis of the arrangement, I examine the ceremonial functions of such experience. In doing so, I explore the three unique features of porcelain’s materiality—two- layeredness, translucency and sheen. To conclude, I argue that the secrecy of the technology of porcelain’s production was the key factor that enabled Augustus II’s demonstration of power. À travers cette thèse, j'examine la collection de porcelaines d'Auguste II « le Fort » au Palais Japonais, un palais à Dresde du 18ème siècle qui abritait des porcelaines provenant de Chine, du Japon et de sa propre manufacture à Meissen. -

Brief History of English and American Literature

Brief History of English and American Literature Henry A. Beers Brief History of English and American Literature Table of Contents Brief History of English and American Literature..........................................................................................1 Henry A. Beers.........................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................6 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER I. FROM THE CONQUEST TO CHAUCER....................................................................11 CHAPTER II. FROM CHAUCER TO SPENSER................................................................................22 CHAPTER III. THE AGE OF SHAKSPERE.......................................................................................34 CHAPTER IV. THE AGE OF MILTON..............................................................................................50 CHAPTER V. FROM THE RESTORATION TO THE DEATH OF POPE........................................63 CHAPTER VI. FROM THE DEATH OF POPE TO THE FRENCH REVOLUTION........................73 CHAPTER VII. FROM THE FRENCH REVOLUTION TO THE DEATH OF SCOTT....................83 CHAPTER VIII. FROM THE DEATH OF SCOTT TO THE PRESENT TIME.................................98 CHAPTER -

Spring 2017 • May 7, 2017 • 12 P.M

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY 415TH COMMENCEMENT SPRING 2017 • MAY 7, 2017 • 12 P.M. • OHIO STADIUM Presiding Officer Commencement Address Conferring of Degrees in Course Michael V. Drake Abigail S. Wexner Colleges presented by President Bruce A. McPheron Student Speaker Executive Vice President and Provost Prelude—11:30 a.m. Gerard C. Basalla to 12 p.m. Class of 2017 Welcome to New Alumni The Ohio State University James E. Smith Wind Symphony Conferring of Senior Vice President of Alumni Relations Russel C. Mikkelson, Conductor Honorary Degrees President and CEO Recipients presented by The Ohio State University Alumni Association, Inc. Welcome Alex Shumate, Chair Javaune Adams-Gaston Board of Trustees Senior Vice President for Student Life Alma Mater—Carmen Ohio Charles F. Bolden Jr. Graduates and guests led by Doctor of Public Administration Processional Daina A. Robinson Abigail S. Wexner Oh! Come let’s sing Ohio’s praise, Doctor of Public Service National Anthem And songs to Alma Mater raise; Graduates and guests led by While our hearts rebounding thrill, Daina A. Robinson Conferring of Distinguished Class of 2017 Service Awards With joy which death alone can still. Recipients presented by Summer’s heat or winter’s cold, Invocation Alex Shumate The seasons pass, the years will roll; Imani Jones Lucy Shelton Caswell Time and change will surely show Manager How firm thy friendship—O-hi-o! Department of Chaplaincy and Clinical Richard S. Stoddard Pastoral Education Awarding of Diplomas Wexner Medical Center Excerpts from the commencement ceremony will be broadcast on WOSU-TV, Channel 34, on Monday, May 8, at 5:30 p.m. -

Volume 58, Number 01 (January 1940) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1940 Volume 58, Number 01 (January 1940) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 58, Number 01 (January 1940)." , (1940). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/265 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. January THE ETUDE 1940 Price 25 Cents music mu — 2 d FOR LITTLE TOT PIANO PLAYERS “Picuurl cote fa-dt Wc cocUcUA. Aeouda them jot cJiddA&i /p ^cnJUni flidi ffiTro JEKK1HS extension piano SHE PEDAL AND FOOT REST Any child (as young as 5 years) with this aid can 1 is prov ided mmsiS(B mmqjamflm® operate the pedals, and a platform Successful Elementary on which to rest his feet obviating dang- . his little legs. The Qualities ling of Published monthly By Theodore presser Co., Philadelphia, pa. Teaching Pieces Should Have EDITORIAL AND ADVISORY STAFF THEODORE PRESSER CO. DR. JAMES FRANCIS COOKE, Editor Direct Mail Service on Everything in Music Publications. TO PUPIL Dr. Edward Ellsworth Hipsher, Associate Editor /EDUCATIONAL POINTS / APPEALING William M. Felton, Music Editor 1712 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise. -

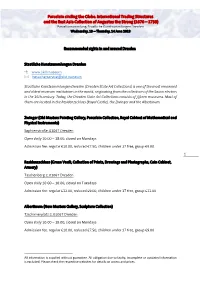

Porcelain Circling the Globe. International Trading Structures And

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of twelve museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

Paperny Films Fonds

Paperny Films fonds Compiled by Melanie Hardbattle and Christopher Hives (2007) Revised by Emma Wendel (2009) Last revised May 2011 University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Paperny Film Inc. series o David Paperny series o A Canadian in Korea: A Memoir series o A Flag for Canada series o B.C. Times series o Call Me Average series o Celluloid Dreams series o Chasing the Cure series o Crash Test Mommy (Season I) series o Every Body series o Fallen Hero: The Tommy Prince Story series o Forced March to Freedom series o Indie Truth series o Mordecai: The Life and Times of Mordecai Richler series o Murder in Normandy series o On the Edge: The Life and Times of Nancy Greene series o On Wings and Dreams series o Prairie Fire: The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 series o Singles series o Spring series o Star Spangled Canadians series o The Boys of Buchenwald series o The Dealmaker: The Life and Times of Jimmy Pattison series o The Life and Times of Henry Morgentaler series o Titans series o To Love, Honour and Obey series o To Russia with Fries series o Transplant Tourism series o Victory 1945 series o Brewery Creek series o Burn Baby Burn series o Crash Test Mommy, Season II-III series o Glutton for Punishment, Season I series o Kink, Season I-V series o Life and Times: The Making of Ivan Reitman series o My Fabulous Gay Wedding (First Comes Love), Season I series o New Classics, Season II-V series o Prisoner 88 series o Road Hockey Rumble, Season I series o The Blonde Mystique series o The Broadcast Tapes of Dr. -

NIKY WARDLEY the EIGHTH DOCTOR’S NEW COMPANION TALKS

ISSUE #20 OCTOBER 2010 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE NIKY WARDLEY THE EIGHTH DOCTOR’S NEW COMPANION TALKS ALSO... FRIENDS OF DEATH IN WHO is MERVYN STONE? BENNY THE FAMILY Nev Fountain explains Miles Richardson and Steven Hall on writing for BACK TO E-SPACE Louise Faulkner the Seventh Doctor with Andrew Smith EDITORIAL Hello from the rehearsal rooms of Doctor Who includes Terry Molloy and even the great Gary Live at Elstree Studios. I’m not allowed to tell you Russell himself. anything at all about it, otherwise a beam will And talk of that great man brings me to zap down from the BBC Worldwide mothership the upcoming return of Gallifrey. Yes, due and destroy my brain. But suffice it to say that it’s to unrelenting popular demand, I went to my all lots of fun. And perhaps it would be okay to illustrious predecessor and begged him on reveal that seeing a load of young girls bobbing bended knee to bring back that popular series. around in Dalek bottoms (!) is quite a thrill for a I’m so delighted that Gary took up the challenge man of my advancing years. and know that the many fans of Gallifrey will Now, back to the world of Big Finish. I hope not be disappointed by the amazing fourth series you haven’t been too wrong-footed by the he is currently creating… with a fantastic cast! change in our podcast regime. Because I’m Right, back to the rehearsals. The Cybermen away, we’re giving you a couple of celebrity are marching… where’s my microphone? podcasts, plus a new podcast with David Richardson talking to a truly stellar line-up, which Nicholas Briggs SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical – The Audiobook Six of the best from Robert Shearman’s critically acclaimed, triple award-winning short story collection, performed to perfection by India Fisher, Toby Hadoke and Jane Goddard, and directed by Rob himself. -

Bach's Organ World Tour of Germany

Bach’s Organ World Tour of Germany for Organists & Friends June 2 - 11, 2020 (10 days, 8 nights) There will be masterclasses and opportunity for organists to play many of the organs visited. Non- organists are welcome to hear about/listen to the organs or explore the tour cities in more depth Day 1 - Tuesday, June 2 Departure Overnight flights to Berlin, Germany (own arrangements or request from Concept Tours). Day 2 - Wednesday, June 3 Arrival/Dresden Guten Tag and welcome to Berlin! (Arrival time to meet for group transfer tbd.) Meet your English-speaking German tour escort who’ll be with you throughout the tour. Board your private bus for transfer south to Dresden, a Kunststadt (City of Art) along the graceful Elbe River. Dresden’s glorious architecture was reconstructed in advance of the city’s 800th anniversary. Highlights include the elegant Zwinger Palace and the baroque Hofkirche (Court Church). Check in to hotel for 2 nights. Welcome dinner and overnight. Day 3 - Thursday, June 4 Dresden This morning enjoy a guided walking tour of Dresden. Some of the major sights you'll see: the Frauenkirche; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Painting Gallery of Old Masters); inside the Zwinger; the majestic Semper Opera House; Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vaults); the Brühlsche Terrasse overlooking the River Elbe. Free time afterwards for your own explorations. 3pm Meet at the Kreuzkirche to attend the organ recital “Orgel Punkt 3”. Visit Hofkirche and have a resident organist (tbc) demonstrate the Silbermann organ, followed by some organ time for members. Day 4 - Friday, June 5 Freiberg/Pomssen/Leipzig After breakfast, check out, board bus and depart.