Dissertation Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View PDF Editionarrow Forward

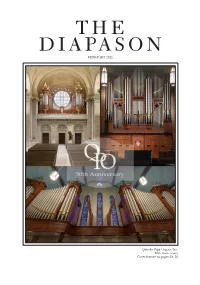

THE DIAPASON FEBRUARY 2021 Quimby Pipe Organs, Inc. 50th Anniversary Cover feature on pages 18–20 PHILLIP TRUCKENBROD CONCERT ARTISTS ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO PETER RICHARD CONTE LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD MARTIN JEAN BÁLINT KAROSI JEAN-WILLY KUNZ HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE ROBERT MCCORMICK JACK MITCHENER BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAÚL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN JOSHUA STAFFORD CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO W͘K͘ŽdžϰϯϮ ĞĂƌďŽƌŶ,ĞŝŐŚƚƐ͕D/ϰဒϭϮϳ ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ĞŵĂŝůΛĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ ဒϲϬͲϱϲϬͲϳဒϬϬ ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚ WŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH SEBASTIAN HEINDL INSPIRATIONS ENSEMBLE ϮϬϭဓ>ÊĦóÊÊ'ÙÄÝ /ÄãÙÄã®ÊĽKÙ¦Ä ÊÃÖã®ã®ÊÄt®ÄÄÙ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Twelfth Year: No. 2, 20 Under 30 Whole No. 1335 We thank the many people who submitted nominations for FEBRUARY 2021 our 20 Under 30 Class of 2021. Nominations closed on Feb- Established in 1909 ruary 1. We will reveal our awardees in the May issue, with Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 biographical information and photographs! 847/954-7989; [email protected] www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, A gift subscription is always appropriate. the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music Remember, a gift subscription of The Diapason for a In this issue friend, colleague, or student is a gift that is remembered each Gunther Göttsche surveys organs and organbuilding in the CONTENTS month. (And our student subscription rate cannot be beat at Holy Land. There are approximately sixty pipe organs in this FEATURES $20/year!) Subscriptions can be ordered by calling our sub- region of the world. -

12 Days Explore Turkey - Armenia - Georgia Tour

Full Itinerary & Trip Details 12 DAYS EXPLORE TURKEY - ARMENIA - GEORGIA TOUR Istanbul Tour - Bosphorus and Two Continents - Yerevan, Garni - Geghard, Khor Virap - Noravank - Areni - Selim - Sevan - Dilijan - Haghatsin - Alaverdi - Haghpat - Sanahin - Sadakhlo border - Tbilisi - Mtskheta - Gudauri - Kutaissi - Kutaisi and Gori PRICE STARTING FROM DURATION TOUR ID € 0 € 0 12 days 932 ITINERARY Day 1 : Istanbul - Arrival Day Meet at the Istanbul international Ataturk airport and transfer to your hotel. You will be given your room key and the rest of the day is yours to explore Istanbul. Overnight in Istanbul. Day 2 : Istanbul Tour Breakfast Included Guided Istanbul walking old city tour visiting Topkapi Palace (closed on tuesdays) Hippodrome, Blue Mosque, Aya Sophia Museum (closed on mondays), Underground Cistern, Covered Grand Bazaar (closed on sundays). Overnight in Istanbul. Day 3 : Bosphorus and Two Continents Breakfast Included Pick up at 08:30 from the hotel for the tour of Bosphorus and the Asian part of Istanbul. During the tour we will enjoy a Bosphorus Cruise, having lunch and visiting the Dolmabahce Palace, Bosphorus Bridge, Asian side.Overnight in Istanbul Day 4 : Istanbul - Yerevan - Armenia Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner Included After breakfast check out from the hotel and depart for Istanbul Ataturk International airport. Arrive to Yerevan and you will be transferred from airport to your hotel by one of official guide of Murti’s tour. Check into the hotel where your accommodation has been reserved for the night. You will be given your room key and the rest of the day is yours to enjoy party and explore to Yerevan. Day 5 : Garni - Geghard Breakfast, Lunch and Dinner Included After breakfast you will depart for a guided city tour Garni and Geghard. -

Wonders of Germany & Austria

WONDERS OF GERMANY & AUSTRIA with Oberammergau 2020 7 May 2020 15 Days from $5,499 This tour takes advantage of the European spring season, with the beauty and mild weather. There’ll be plenty of time to enjoy some of the great German-speaking cities of central Europe – Berlin, Dresden and Vienna; experiencing the life, culture, religion and history of these cities. Archdeacon John Davis leads this tour, his second time to Oberammergau. He is the former Vicar General of the Anglican Diocese of Wangarattta. John has led several groups to Assisi, as well as to Oberammergau. Archdeacon John Davis Tour INCLUSIONS • 12 nights’ accommodation at 4 star hotels as listed • Oberammergau package including 1 nights (or similar) with breakfast daily accommodation, category 2 ticket and dinner • 5 dinners in hotels; 3 dinners in local restaurants • Services of a professional English-speaking Travel • Lunch at the Hofbrahaus Director throughout. Local expert guides where required & as noted on the itinerary • Sightseeing and entrance fees as outlined in the itinerary • Tips to Travel Director and Driver • Luxury air-conditioned coach with panoramic • Archdeacon John Davis as your host windows myselah.com.au 1300 230 271 ITINERARY Summarised Friday 8 May Saturday 16 May BERLIN OBERAMMERGAU Free day to explore. Drive to Oberammergau (travel time approx. 90 mins). Spend some free time in the quaint village Saturday 9 May before the Passion Play performance beings BERLIN at 2.30pm. There is a dinner break followed Today we will visit the two cathedrals in the Mitte by the second half of the play, concluding at area (Berlin Cathedral and St Hedwig’s) before an approximately 10.30pm. -

Submitted to the Faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University December, 2015

A HANDBOOK FOR INTRODUCING UNDERGRADUATES TO THE ORGAN AND ITS LITERATURE BY PATRICK EUGENE POPE Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University December, 2015 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. ___________________________________ Katherine Strand, Research Director __________________________________ Christopher Young, Chairperson __________________________________ Mary Ann Hart __________________________________ Marilyn Keiser September 17, 2015 ii Copyright © 2015 Patrick E. Pope iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to acknowledge his organ teachers and professors, whose instruction led to a discerned need for this handbook and its creation: Donnie Beddingfield (1994-1998); William Bates (1998-2002); Marilyn Keiser (2002-2004); Todd Wilson (2008- 2009); and Christopher Young (2009-present). Their love and passion for teaching, performing, and researching has kindled the writer’s interest in the organ, its music, and its literature. The writer is a better musician because of their wisdom and encouragement. The writer wishes to thank the Reverend Kevin Brown, rector, and the parish of Holy Comforter Episcopal Church, Charlotte, North Carolina for their encouragement during the final stages of the doctoral degree. The writer wishes to thank the members of his doctoral research committee and other faculty for their guidance and professional support: Katherine Strand, research director; Christopher Young, chairperson; Janette Fishell; Marilyn Keiser; Mary Ann Hart; and Bruce Neswick. In particular, the writer is grateful to Professor Young for his insightful and energizing classroom teaching in a four-semester organ literature survey at Indiana University, in which the writer was privileged to take part during master’s and doctoral coursework. -

Augustus II the Strong's Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches

Augustus II the Strong’s Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches Palais zu Dresden: A Visual Demonstration of Power and Splendor Zifeng Zhao Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal September 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Zifeng Zhao 2018 i Abstract In this thesis, I examine Augustus II the Strong’s porcelain collection in the Japanisches Palais, an 18th-century Dresden palace that housed porcelains collected from China and Japan together with works made in his own Meissen manufactory. I argue that the ruler intended to create a social and ceremonial space in the chinoiserie style palace, where he used a systematic arrangement of the porcelains to demonstrate his kingly power as the new ruler of Saxony and Poland. I claim that such arrangement, through which porcelains were organized according to their colors and styles, provided Augustus II’s guests with a designated ceremonial experience that played a significant role in the demonstration of the King’s political and financial prowess. By applying Gérard de Lairesse’s color theory and Samuel Wittwer’s theory of “the phenomenon of sheen” to my analysis of the arrangement, I examine the ceremonial functions of such experience. In doing so, I explore the three unique features of porcelain’s materiality—two- layeredness, translucency and sheen. To conclude, I argue that the secrecy of the technology of porcelain’s production was the key factor that enabled Augustus II’s demonstration of power. À travers cette thèse, j'examine la collection de porcelaines d'Auguste II « le Fort » au Palais Japonais, un palais à Dresde du 18ème siècle qui abritait des porcelaines provenant de Chine, du Japon et de sa propre manufacture à Meissen. -

JANUARY, 2010 Cathedral Church of St. Peter Regensburg, Germany

THE DIAPASON JANUARY, 2010 photo credit: Michael Vogl, Regensburg Cathedral Church of St. Peter Regensburg, Germany Cover feature on pages 28–29 Jan 2010 Cover.indd 1 12/14/09 7:25:20 AM Jan 2010 pp. 2-18.indd 2 12/14/09 7:27:04 AM THE DIAPASON Letters to the Editor A Scranton Gillette Publication One Hundred First Year: No. 1, Whole No. 1202 JANUARY, 2010 Gavin Black: On Teaching the fi fties to hear Myra Hess, Burt Lan- Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 I’ve been enjoying Gavin Black’s col- caster walked right past my wife and me, An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, umn “On Teaching” in The Diapason. big deal! the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music Although I don’t have organ students, And Bovard Auditorium (I am a USC I’m learning a lot from the articles. Be- alumnus, grad school, as well as UCLA sides being an organist, I’m also a piano grad)—what memories! I remember the technician. The article about tuning original console well, and Mr. Lewis has CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] systems (September) is, by far, the best it all correct. This was a major loss, which 847/391-1045 description of tuning and tuning systems should not have happened, and I am not FEATURES that I’ve ever read! I’m going to save this alone in my opinion. It was a powerful Poulenc and Durufl é ‘premieres’ in Woolsey Hall Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON issue in case I have to give a talk about and impressive instrument. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

Musical (And Other) Gems from the State Library in Dresden

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 23, Number 20, May 10, 1996 Reviews Musical (and other) gems from the State Libraryin Dresden by Nora Hamennan One might easily ask how anything could be left of what was scribe, and illuminations by a Gentile artist painted in Chris once the glorious collection of books and manuscripts which tian Gothic style. An analogous "cross-cultural" blend is were the Saxon Royal Library, and then after 1918, Saxon shown in two French-language illuminated manuscripts of State Library in Dresden. After all, Dresden was razed to the works by Boccaccio and Petrarca, respectively, two of the ground by the infamous Allied firebombing in 1945, which "three crowns" of Italian 14th-century vernacular literature, demolished the Frauenkirche and the "Japanese Palace" that produced in the 15th-century French royal courts. Then had housed the library's most precious holdings, as well as comes a printed book, with hand-painted illuminations, of taking an unspeakable and unnecessary toll in innocent hu 1496, The Performanceo/Music in Latin by Francesco Gaffu man lives. Then, the Soviets, during their occupation of the rius, the music theorist whose career at the Milan ducal court eastern zone of Germany, carried off hundreds of thousands overlapped the sojourns there of Josquin des Prez, the most of volumes, most of which have not yet been repatriated. renowned Renaissance composer, and Leonardo da Vinci, The question is partially answered in the exhibit, "Dres regarded by contemporaries as the finestimprovisational mu den: Treasures from the Saxon State Library," on view at the sician. -

View PDF Editionarrow Forward

T H E DIAPASON APRIL 2019 American Organ Institute University of Oklahoma Norman, Oklahoma Cover feature on pages 22–23 PHILLIP TRUCKENBROD CONCERT ARTISTS ANTHONY & BEARD ADAM J. BRAKEL THE CHENAULT DUO PETER RICHARD CONTE CONTE & ENNIS DUO LYNNE DAVIS ISABELLE DEMERS CLIVE DRISKILL-SMITH DUO MUSART BARCELONA JEREMY FILSELL MICHAEL HEY HEY & LIBERIS DUO CHRISTOPHER HOULIHAN DAVID HURD SIMON THOMAS JACOBS MARTIN JEAN HUW LEWIS RENÉE ANNE LOUPRETTE LOUPRETTE & GOFF DUO ROBERT MCCORMICK BRUCE NESWICK ORGANIZED RHYTHM RAéL PRIETO RAM°REZ JEAN-BAPTISTE ROBIN ROBIN & LELEU DUO BENJAMIN SHEEN HERNDON SPILLMAN CAROLE TERRY JOHANN VEXO BRADLEY HUNTER WELCH JOSHUA STAFFORD THOMAS GAYNOR 2016 2017 LONGWOOD GARDENS ST. ALBANS WINNER WINNER IT’S ALL ABOUT THE ART ǁǁǁ͘ĐŽŶĐĞƌƚĂƌƟƐƚƐ͘ĐŽŵ 860-560-7800 ŚĂƌůĞƐDŝůůĞƌ͕WƌĞƐŝĚĞŶƚͬWŚŝůůŝƉdƌƵĐŬĞŶďƌŽĚ͕&ŽƵŶĚĞƌ THE DIAPASON Editor’s Notebook Scranton Gillette Communications One Hundred Tenth Year: No. 4, 20 Under 30 Whole No. 1313 We thank all those who submitted nominations for our Class APRIL 2019 of 2019. We are impressed by the number of f ne nominations Established in 1909 for the brightest and most promising our young leaders in the Stephen Schnurr ISSN 0012-2378 f eld of the organ, church music, harpsichord, and carillon. 847/954-7989; [email protected] To see the 20 Under 30 Class of 2019, visit The Diapason www.TheDiapason.com An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, website (www.thediapason.com, click on “20 Under 30”). Next the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music month’s issue will include in-depth entries and photographs of In “Harpsichord Notes,” Larry Palmer reprises various front- each member of the class. -

The Effect of War on Art: the Work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Doland, Elizabeth Leigh, "The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2986. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF WAR ON ART: THE WORK OF MARK ROTHKO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Elizabeth Doland B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 May 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………iii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………........1 2 EARLY LIFE……………………………………………………....3 Yale Years……………………………………………………6 Beginning Life as Artist……………………………………...7 Milton Avery…………………………………………………9 3 GREAT DEPRESSION EFFECTS………………………………...13 Artists’ Union………………………………………………...15 The Ten……………………………………………………….17 WPA………………………………………………………….19 -

Symbol of Conquest, Alliance, and Hegemony

SYMBOL OF CONQUEST, ALLIANCE, AND HEGEMONY: THE IMAGE OF THE CROSS IN COLONIAL MEXICO by ZACHARY WINGERD Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON August 2008 Copyright © by Zachary Wingerd 2008 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I offer thanks to Dr. Dennis Reinhartz, Dr. Kenneth Philp, Dr. Richard Francaviglia, and Dr. Joseph Bastien who agreed to sit on my dissertation committee and guide my research and writing. Special thanks are given to Dr. Douglas Richmond who encouraged my topic from the very beginning and as the committee chair actively supported my endeavor. May 1, 2008 iii DEDICATED TO MY LOVING WIFE AND SONS Lindsey, Josh, and Jamie iv ABSTRACT SYMBOL OF CONQUEST, ALLIANCE, AND HEGEMONY: THE IMAGE OF THE CROSS IN COLONIAL MEXICO Zachary Wingerd, PhD. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2008 Supervising Professor: Douglas Richmond The universality of the cross image within the transatlantic confrontation meant not only a hegemony of culture, but of symbolism. The symbol of the cross existed in both European and American societies hundreds of years before Columbus. In both cultures, the cross was integral in religious ceremony, priestly decoration, and cosmic maps. As a symbol of life and death, of human and divine suffering, of religious and political acquiescence, no other image in transatlantic history has held such a perennial, powerful message as the cross. For colonial Mexico, which felt the brunt of Spanish initiative, the symbol of the cross penetrated the autochthonous culture out of which the independent nation and indigenous church were born. -

Architecture, German Identity, and Historical Memory After 1945

THE GERMANIC REVIEW From Frankfurt's Goethehaus to Dresden's Frauenkirche: Architecture, German Identity, and Historical Memory after 1945 SUSANNE VEES-GULANI otions of identity are often linked to specific places and spaces. N Cultural identity is usually rooted within communities that share traditions and a location within a certain geographical region. On a smaller scale, cultural identity is inadvertently tied to the physical structures and the architectural design organizing these spaces. Some groups, for example, might identify with a strong sense of the future and aspire to demonstrate their modernity by erecting contemporary buildings and structures, while others define themselves through his- torical sites (Layton and Thomas 1-2). The former case often leads to the destruction of historical remains to create space for the new; the latter frequently results in far-reaching conservation efforts to pre- serve remnants from the past. Since the late eighteenth century, particularly in many Western na- tions, such conservation efforts have increased, as sites and struc- tures from previous times began to function as visible confirmations of historical and national identity (Hunter 27-28). In the twentieth cen- tury, preservation of historical buildings and places reached new heights (Larkham 39), marking the emphasis many cultures now place on what they consider their heritage. In addition to historicist and nationalist arguments, this trend can be explained by current ex- periences. Maintaining and restoring historical sites lend stability to a world marked by large-scale destruction of familiar environments dur- ing war and rapid urban development, an unease with the modern sit- uation that seems to offer less possibilities of clearly and easily defin- ing oneself, and the fear of an uncertain future (Lowenthal 38).