The Integration of Emory & Henry College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Red Flag Campaign

objectives • Red Flag Campaign development process • Core elements of the campaign • How the campaign uses prevention messages to emphasize and promote healthy dating relationships • Campus implementation ideas prevalence • Women age 16 to 24 experience the highest per capita rate of intimate partner violence. C. Rennison and S. Welchans, “Intimate Partner Violence” U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, May 2000. • In 1 in 5 college dating relationships, one of the partners is being abused. C. Sellers and M. Bromley, “Violent Behavior in College Student Dating Relationships,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice (1996) 1 key players • Advisory committee • College student focus groups development process preliminary focus groups • March 2006, four focus groups held with college students • Two women’s groups; two men’s groups • Students said they were willing to intervene with friends who are being victimized by or acting abusively towards their dates • Students also indicated they would be receptive to hearing intervention and prevention messages from their friends 2 developing core messages • Target college students who are friends/peers of victims and perpetrators of dating violence – Educate friends/peers about ‘red flags’ (warning indicators) of dating violence – Encourage friends/peers to ‘say something’ (intervene in the situation) Social Ecological Model Address norms or customs or people’s experience with local institutions Change in person’s Address influence of knowledge, attitude, peers and intimate behavior partners Address broad social forces, such as inequality, oppression, and broad public policy changes. 3 focus group: example of edits “He told me I was fat and stupid and no one else would want me … … maybe he’s right.” "I told her ‘That’s wrong. -

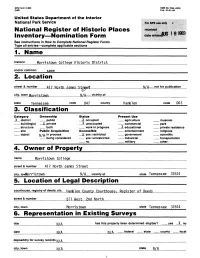

Nomination Form See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries—Complete Applicable Sections______1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections________________ 1. Name historic Morris town College Historic District and/or common same 2. Location street & number 417 North James N/ not for publication city, town Morristown N/A — vicinity of state Tennessee code 047 county Hambl en code 063 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public _ X_ occupied agriculture museum building(s) _ X- private _ X_ unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress _ X_ educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A- in Process _ X- yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Morristown College street & number 417 North James Street city, towMorris town N/A_ vicinity of state Tennessee 37814 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Hamblen County Courthouse, Register of Deeds street & number____________511 West 2nd North________ city, town Morristown state Tennessee 37814 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title has this property been determined eligible? date _N/A, federal __ state __ county __ local depository for survey records [\j//\ city, town state N/A 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _ X original site _J(_good ruins X altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Morristown College Historic District is located in Morristown, Tennessee (pop. -

The Bennett Banner

ARCHIVES Bennett Colloga G/^eensb'ofo, II c . “Living Christmas Madonnas” THE BENNETT< BANNER Dec, 7— 7 p. m. “Believing that an informed campus is a Key to Democracy’’ VOL. XXVI, NO. Ill GREENSBORO, NORTH CAROLINA NOVEMBER, 1958 Morehouse Sives Ten Girls Elected Itnnual Concert To College Highlighting the annual More Who's Who house College Glee Club visit Ten Bennett students—nine sen was the combined singing of the iors and one junior—have been Morehouse Glee Club and the Ben selected to “Who’s Who Among nett Choir in three musical com Students in American Colleges and positions. Universities” for the academic The selections were “In the year 1958-59. Year That King Uzziah Died,” ar These seniors so honored are: ranged by David McK. Williams; “Rejoice In the Lamb,” a festival Hudene Abney of Norristown, cantata, with music by Benjamin Pennsylvania, a pre-law student Britten; and “Alleluia,” by Randall who is spending her senior year Thompson. tudying at the American Univer These outstanding works were sity, Washington, D. C., under one sung first on Friday, November of Bennett’s cooperative programs. 28, during the chapel period. The Barbara Campbell of Greens concert was held Friday night boro, North Carolina, English at 8 o’clock in the Annie Merner major, editor of the Bennett Ban Pfeiffer Chapel. ner, and a member of Alpha Kap The combined singing of the two pa Mu Honor Siciety. choral groups, as well as the con Jamesena Chalmers of Fayette certs (Bennett appears at More ville, North Carolina, English house in the spring), have become major, president of the Student annual events. -

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards Full and complete nomination submissions must be received by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia no later than 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. Please direct questions and comments to: Ms. Ashley Lockhart, Coordinator for Academic Initiatives State Council of Higher Education for Virginia James Monroe Building, 10th floor 101 N. 14th St., Richmond, VA 23219 Telephone: 804-225-2627 Email: [email protected] Sponsored by Dominion Energy VIRGINIA OUTSTANDING FACULTY AWARDS To recognize excellence in teaching, research, and service among the faculties of Virginia’s public and private colleges and universities, the General Assembly, Governor, and State Council of Higher Education for Virginia established the Outstanding Faculty Awards program in 1986. Recipients of these annual awards are selected based upon nominees’ contributions to their students, academic disciplines, institutions, and communities. 2022 OVERVIEW The 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards are sponsored by the Dominion Foundation, the philanthropic arm of Dominion. Dominion’s support funds all aspects of the program, from the call for nominations through the award ceremony. The selection process will begin in October; recipients will be notified in early December. Deadline for submission is 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. The 2022 Outstanding Faculty Awards event is tentatively scheduled to be held in Richmond sometime in February or March 2022. Further details about the ceremony will be forthcoming. At the 2022 event, at least 12 awardees will be recognized. Included among the awardees will be two recipients recognized as early-career “Rising Stars.” At least one awardee will also be selected in each of four categories based on institutional type: research/doctoral institution, masters/comprehensive institution, baccalaureate institution, and two-year institution. -

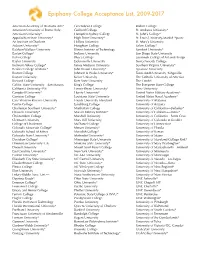

Epiphany Comprehensive College List

Epiphany College Acceptance List, 2009-2017 American Academy of Dramatic Arts* Greensboro College Rollins College American University of Rome (Italy) Guilford College St. Andrews University* American University* Hampden-Sydney College St. John’s College* Appalachian State University* High Point University* St. Louis University-Madrid (Spain) Art Institute of Charlotte Hollins University St. Mary’s University Auburn University* Houghton College Salem College* Baldwin Wallace University Illinois Institute of Technology Samford University* Barton College* Indiana University San Diego State University Bates College Ithaca College Savannah College of Art and Design Baylor University Jacksonville University Sierra Nevada College Belmont Abbey College* James Madison University Southern Virginia University* Berklee College of Music* John Brown University* Syracuse University Boston College Johnson & Wales University* Texas A&M University (Kingsville) Boston University Keiser University The Catholic University of America Brevard College Kent State University The Citadel Califor. State University—San Marcos King’s College The Evergreen State College California University (PA) Lenoir-Rhyne University* Trine University Campbell University* Liberty University* United States Military Academy* Canisius College Louisiana State University United States Naval Academy* Case Western Reserve University Loyola University Maryland University of Alabama Centre College Lynchburg College University of Arizona Charleston Southern University* Manhattan College University -

2007-08 TN HOPE Scholarship Year End Report

7/2/2008 Page 1 of 3 State of Tennessee Tennessee Student Assistance Corporation Awards By Institution Report - Awarded Academic Year 2007-2008 HOPE Scholarship Institution Name Total Awards Summer Fall Winter Spring AQUINAS COLLEGE 003477-00 41 $140,659.00 0 $0.00 40 $77,909.00 0 $0.00 31 $62,750.00 AQUINAS COLLEGE-PRIMETIME E00966-00 7 $26,000.00 0 $0.00 7 $14,000.00 0 $0.00 6 $12,000.00 ART INSTITUTE OF TN, NASHVILLE 009270-00 10 $37,423.00 2 $3,167.00 8 $11,172.00 8 $11,420.00 10 $11,664.00 AUSTIN PEAY STATE UNIVERSITY 003478-00 1910 $7,642,850.00 14 $18,876.00 1834 $4,038,818.50 0 $0.00 1635 $3,585,155.50 BAPTIST MEM CO OF HEALTH SCIENCE 034403-00 126 $488,813.00 6 $6,000.00 118 $253,563.00 0 $0.00 109 $229,250.00 BELMONT UNIVERSITY 003479-00 824 $3,354,000.00 0 $0.00 794 $1,730,000.00 0 $0.00 746 $1,624,000.00 BETHEL COLLEGE 003480-00 267 $1,104,000.00 0 $0.00 255 $571,250.00 0 $0.00 236 $532,750.00 BRYAN COLLEGE 003536-00 205 $871,900.00 0 $0.00 202 $454,525.00 0 $0.00 185 $417,375.00 CARSON NEWMAN COLLEGE 003481-00 674 $2,820,122.00 3 $6,125.00 655 $1,468,410.00 0 $0.00 603 $1,345,587.00 CHATTANOOGA ST TECH COM COL 003998-00 768 $1,519,578.00 0 $0.00 707 $794,943.00 0 $0.00 626 $724,635.00 CHRISTIAN BROTHERS UNIVERSITY 003482-00 515 $2,098,500.00 0 $0.00 506 $1,105,750.00 0 $0.00 446 $992,750.00 CLEVELAND STATE COMM COLLEGE 003999-00 372 $731,417.00 5 $3,946.00 336 $378,204.00 0 $0.00 307 $349,267.00 COLUMBIA STATE COMM COLLEGE 003483-00 794 $1,596,598.00 0 $0.00 728 $851,880.00 0 $0.00 647 $744,718.00 CRICHTON COLLEGE 009982-00 -

Methodism's Splendid Mission: the Black Colleges

Methodist History, 22:3 (April /984) METHODISM'S SPLENDID MISSION: THE BLACK COLLEGES JAMES S. THOMAS In the past, many historians of higher education often accepted the twin generalizations that black colleges, (1) "while collegiate in name, did not remotely resemble a college in standards or facilities,"l and (2) that the history of these colleges, while probably important as early hTi'Ssionary ventures, would hardly rate complete chapters in general histories of higher education. This essay begins as a direct challenge to both points of view. Among otheT propositions, it will be argued (1) that, while the contrast between the facilities and standards ofblack and white colleges is dramatically real, it is by no means an unbroken contrast, and (2) admitting the truth of the missionary beginnings of the early black colleges, there is a much greater story of their survival and their production of a group of leaders whose quality stands high on any national standard of leadership. Indeed, the major purpose of this essay is not to argue a particular point, such as any one of the too-easy generalizations of many historians, but to tell the remarkable story of the black colleges of the United Methodist Church. The Earliest of Foundations The history of the black colleges, like that of all institutional history, J predated the founding of any particular institution. Perhaps it is important 1 for United Methodists to remember, in this bicentennial year, that the founder of Methodism, John Wesley, held very strong views about educa,. tion and the worth of every human being. -

2019-2020 Academic Catalog

2019-2020 Academic Catalog Academic Catalog 2019-2020 Accreditation Tennessee Wesleyan University is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award baccalaureate and masters degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Tennessee Wesleyan University. In addition, Tennessee Wesleyan’s programs have been approved by: The Tennessee State Board of Education The University Senate of the United Methodist Church This catalog presents the program requirements and regulations of Tennessee Wesleyan University in effect at the time of publication. Students enrolling in the University are subject to the provisions stated herein. Statements regarding programs, courses, fees, and conditions are subject to change without advance notice. Tennessee Wesleyan University was founded in 1857. Tennessee Wesleyan University is a comprehensive institution affiliated with theHolston Conference of the United Methodist Church. Tennessee Wesleyan University adheres to the principles of equal education, employment opportunity and participation in collegiate activities without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital or family status, disability or sexual orientation. This policy extends to all programs and activities supported by the University. 3 Table of Contents Academic Calendar 6 Merner-Pfeiffer Library 45 Mission/Purpose 9 Student Success Center 45 Definition of a Church Related -

Emory and Henry College 01/30/1989

VLR Listed: 1/18/1983 NPS Form 10-900 NRHP Listed: 1/30/1989 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Eip. 10-31-84 United States Department of the interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Piaces received OCT 1 ( I935 Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Emory and Henry College (VHLD File No. 95-98) and or common Same 2. Location street & number VA State Route 609 n/a not for publication Emory city, town X vicinity of 51 state Virginia ^^^^ Washington code county 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment -X religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation n/a no military other: 4. Owner of Property name The Holston Conference Colleges Board of Trustees, c/o Dr. Heisse Johnson street & number P.O. Box 1176 city,town Johnson City n/-a vicinity of state Tennessee 37601 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Washington County Courthouse street&number Main Street city.town Abingdon state Virginia 24210 6. Representation in Existing Surveys titieyirginia Historic Landmarks has this property been determined eligible? yes X no Division Survey File No. 95-98 date 1982 federal X_ state county local depository tor survey records Virginia Historic Landmarks divi sion - 221 Governor Street cuv.town Richmond state Virginia 23219 7. -

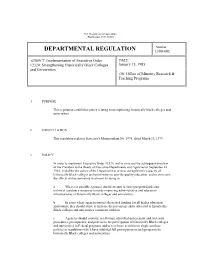

Implementation of Executive Order 12320

U.S. Department of Agriculture Washington, D.C. 20250 Number: DEPARTMENTAL REGULATION 1390-001 SUBJECT: Implementation of Executive Order DATE: 12320: Strengthening Historically Black Colleges January 15, 1985 and Universities OPI: Office of Minority Research & Teaching Programs I PURPOSE This regulation establishes policy relating to strengthening historically black colleges and universities. 2 CANCELLATION This regulation replaces Secretary's Memorandum No. 1978, dated March 12, 1979. 3 POLICY In order to implement Executive Order 12320, and to carry out the subsequent direction of the President to the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies of September 22, 1982, it shall be the policy of the Department to seek to strengthen the capacity of historically Black colleges and universities to provide quality education, and to overcome the effects of discriminatory treatment. In doing so: a Wherever possible agencies should attempt to direct program funds and technical assistance resources towards improving administrative and education infrastructures of historically Black colleges and universities. b In cases where agencies project decreased funding for all higher education institutions, they should strive to increase the percentage share allocated to historically Black colleges and universities consistent with law. c Agencies should continue to eliminate identified unnecessary and irrelevant procedures, prerequisites, and policies to the participation of historically Black colleges and universities in Federal programs and to accelerate activities to single out those policies or regulations which have inhibited full participation in such programs by historically Black colleges and universities. DR 1390-001 January 15, 1985 4 DEFINITIONS Historically Black colleges and universities. Those colleges and universities so designated by the White House Initiative on Historically Black Colleges and Universities, United States Department of Education. -

UB and VUB Projects Funded for 2006-07

UB and VUB Projects Funded for 2006-07 No. of No. of UB Total No. of FY 2006 Regular UB Initiative UB FY 2006 Initiative Total FY 2006 Regular Upward Bound (UB) Grantees State Participants Participants Participants Funding Funding Funding University of Alaska/ Anchorage AK 60 0 60 $ 234,624 $ $ - 234,624 University of Alaska/ Fairbanks AK 140 0 140 $ 752,563 $ $ - 752,563 Alabama A & M University AL 90 0 90 $ 451,158 $ $ - 451,158 Alabama Southern Community College AL 55 20 75 $ 277,677 $ 100,000 $ 377,677 Alabama Southern Community College AL 55 20 75 $ 277,677 $ 100,000 $ 377,677 Alabama Southern Community College/ Monroe Campus AL 57 20 77 $ 287,702 $ 100,000 $ 387,702 Alabama State University/ Montgomery AL 57 0 57 $ 284,229 $ $ - 284,229 Bevill State Community College/ Fayette AL 88 20 108 $ 352,509 $ 100,000 $ 452,509 Bevill State Community College/ Hamilton AL 56 0 56 $ 279,496 $ $ - 279,496 Bevill State Community College/ Sumiton AL 60 20 80 $ 274,895 $ 100,000 $ 374,895 Bishop State Community College AL 50 0 50 $ 244,589 $ $ - 244,589 Calhoun Community College AL 66 20 86 $ 331,752 $ 100,000 $ 431,752 Central Alabama Community College AL 80 0 80 $ 294,840 $ $ - 294,840 Concordia College AL 80 0 80 $ 394,447 $ $ - 394,447 Enterprise-Ozark Community College AL 50 0 50 $ 234,624 $ $ - 234,624 Faulkner State Community College AL 60 0 60 $ 287,703 $ $ - 287,703 Gadsden State Community College AL 65 20 85 $ 287,703 $ 100,000 $ 387,703 George C. -

175 Subpart A—General

Ofc. of Postsecondary Educ., Education § 608.2 SOURCE: 58 FR 38713, July 20, 1993, unless Tuskegee University—Tuskegee otherwise noted. ARKANSAS Subpart A—General Arkansas Baptist College—Little Rock Philander Smith College—Little Rock § 608.1 What is the Strengthening His- Shorter College—Little Rock torically Black Colleges and Univer- University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff—Pine sities (HBCU) Program? Bluff The Strengthening Historically DELAWARE Black Colleges and Universities Pro- Delaware State College—Dover gram, hereafter called the HBCU Pro- gram, provides grants to Historically DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Black Colleges and Universities Howard University (HBCUs) to assist these institutions in University of the District of Columbia establishing and strengthening their physical plants, academic resources FLORIDA and student services so that they may Bethune Cookman College—Daytona Beach continue to participate in fulfilling the Edward Waters College—Jacksonville goal of equality of educational oppor- Florida A&M University—Tallahassee tunity. Florida Memorial College—Miami (Authority: 20 U.S.C. 1060) GEORGIA Albany State College—Albany § 608.2 What institutions are eligible to Atlanta University—Atlanta receive a grant under the HBCU Clark College—Atlanta Program? Fort Valley State College—Fort Valley (a) To be eligible to receive a grant Interdenominational Theological Center— under this part, an institution must— Atlanta (1) Satisfy section 322(2) of the Higher Morehouse College—Atlanta Morris Brown College—Atlanta Education Act of 1965,