The Smithfield Review Volume XII, 2008 Vejnar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Red Flag Campaign

objectives • Red Flag Campaign development process • Core elements of the campaign • How the campaign uses prevention messages to emphasize and promote healthy dating relationships • Campus implementation ideas prevalence • Women age 16 to 24 experience the highest per capita rate of intimate partner violence. C. Rennison and S. Welchans, “Intimate Partner Violence” U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, May 2000. • In 1 in 5 college dating relationships, one of the partners is being abused. C. Sellers and M. Bromley, “Violent Behavior in College Student Dating Relationships,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice (1996) 1 key players • Advisory committee • College student focus groups development process preliminary focus groups • March 2006, four focus groups held with college students • Two women’s groups; two men’s groups • Students said they were willing to intervene with friends who are being victimized by or acting abusively towards their dates • Students also indicated they would be receptive to hearing intervention and prevention messages from their friends 2 developing core messages • Target college students who are friends/peers of victims and perpetrators of dating violence – Educate friends/peers about ‘red flags’ (warning indicators) of dating violence – Encourage friends/peers to ‘say something’ (intervene in the situation) Social Ecological Model Address norms or customs or people’s experience with local institutions Change in person’s Address influence of knowledge, attitude, peers and intimate behavior partners Address broad social forces, such as inequality, oppression, and broad public policy changes. 3 focus group: example of edits “He told me I was fat and stupid and no one else would want me … … maybe he’s right.” "I told her ‘That’s wrong. -

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards Full and complete nomination submissions must be received by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia no later than 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. Please direct questions and comments to: Ms. Ashley Lockhart, Coordinator for Academic Initiatives State Council of Higher Education for Virginia James Monroe Building, 10th floor 101 N. 14th St., Richmond, VA 23219 Telephone: 804-225-2627 Email: [email protected] Sponsored by Dominion Energy VIRGINIA OUTSTANDING FACULTY AWARDS To recognize excellence in teaching, research, and service among the faculties of Virginia’s public and private colleges and universities, the General Assembly, Governor, and State Council of Higher Education for Virginia established the Outstanding Faculty Awards program in 1986. Recipients of these annual awards are selected based upon nominees’ contributions to their students, academic disciplines, institutions, and communities. 2022 OVERVIEW The 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards are sponsored by the Dominion Foundation, the philanthropic arm of Dominion. Dominion’s support funds all aspects of the program, from the call for nominations through the award ceremony. The selection process will begin in October; recipients will be notified in early December. Deadline for submission is 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. The 2022 Outstanding Faculty Awards event is tentatively scheduled to be held in Richmond sometime in February or March 2022. Further details about the ceremony will be forthcoming. At the 2022 event, at least 12 awardees will be recognized. Included among the awardees will be two recipients recognized as early-career “Rising Stars.” At least one awardee will also be selected in each of four categories based on institutional type: research/doctoral institution, masters/comprehensive institution, baccalaureate institution, and two-year institution. -

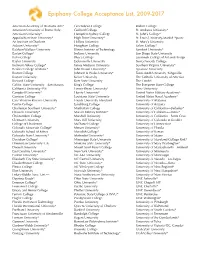

Epiphany Comprehensive College List

Epiphany College Acceptance List, 2009-2017 American Academy of Dramatic Arts* Greensboro College Rollins College American University of Rome (Italy) Guilford College St. Andrews University* American University* Hampden-Sydney College St. John’s College* Appalachian State University* High Point University* St. Louis University-Madrid (Spain) Art Institute of Charlotte Hollins University St. Mary’s University Auburn University* Houghton College Salem College* Baldwin Wallace University Illinois Institute of Technology Samford University* Barton College* Indiana University San Diego State University Bates College Ithaca College Savannah College of Art and Design Baylor University Jacksonville University Sierra Nevada College Belmont Abbey College* James Madison University Southern Virginia University* Berklee College of Music* John Brown University* Syracuse University Boston College Johnson & Wales University* Texas A&M University (Kingsville) Boston University Keiser University The Catholic University of America Brevard College Kent State University The Citadel Califor. State University—San Marcos King’s College The Evergreen State College California University (PA) Lenoir-Rhyne University* Trine University Campbell University* Liberty University* United States Military Academy* Canisius College Louisiana State University United States Naval Academy* Case Western Reserve University Loyola University Maryland University of Alabama Centre College Lynchburg College University of Arizona Charleston Southern University* Manhattan College University -

Emory and Henry College 01/30/1989

VLR Listed: 1/18/1983 NPS Form 10-900 NRHP Listed: 1/30/1989 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Eip. 10-31-84 United States Department of the interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Piaces received OCT 1 ( I935 Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Emory and Henry College (VHLD File No. 95-98) and or common Same 2. Location street & number VA State Route 609 n/a not for publication Emory city, town X vicinity of 51 state Virginia ^^^^ Washington code county 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment -X religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation n/a no military other: 4. Owner of Property name The Holston Conference Colleges Board of Trustees, c/o Dr. Heisse Johnson street & number P.O. Box 1176 city,town Johnson City n/-a vicinity of state Tennessee 37601 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Washington County Courthouse street&number Main Street city.town Abingdon state Virginia 24210 6. Representation in Existing Surveys titieyirginia Historic Landmarks has this property been determined eligible? yes X no Division Survey File No. 95-98 date 1982 federal X_ state county local depository tor survey records Virginia Historic Landmarks divi sion - 221 Governor Street cuv.town Richmond state Virginia 23219 7. -

A L U M N a E M a G a Z I N E Volume 79

ALUMNAE MAGAZINE VOLUME 79 NUMBER 1 WINTER 2007/2008 NOTE FROM THE hen I was a high school student looking at colleges, I was dragged kicking and screaming to look at Sweet Briar. Sweet Briar touted the refrain that women’s colleges offered far more opportunities than coeducational schools did for Wwomen to become leaders. I was one of those students who matriculated despite the fact, not because it offered single-sex education, and I took the leadership mantra with a grain of salt. After all, I attended a small Catholic high school where everyone seemed to be involved in everything and I could not imagine that women, especially me, needed help with anything. (This was the early 1980s, and I was only 17!) Not until I attended law school did I really begin to recognize what Sweet Briar had given me. Then, as now, College leaders led by example and provided ample opportunities for the studentsalumnae to take a lead somewhere, association somehow. I was involved in presidentall sorts of campus activities as a student and remained involved with Sweet Briar in some capacity since my graduation because I believe so strongly in the Sweet Briar Promise. In my years on the Alumnae Association Board, I have served under the leadership of two fabulous presidents, each of whom I admire for her wisdom, diplomacy, and dedication to our alma mater. I feel privileged Being a leader does not to have been given the opportunity to follow in their footsteps. Although I have served on mean that you have to several boards in my professional and residential communities, Sweet Briar’s Alumnae Board is special to me in the way that Sweet Briar is special to each of us, but for reasons we cannot be in the position at the always articulate. -

The Founding of the Permanent Denominational Colleges in Virginia, 1776-1861

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1976 The founding of the permanent denominational colleges in Virginia, 1776-1861 Stuart Bowe Medlin College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Other Education Commons Recommended Citation Medlin, Stuart Bowe, "The founding of the permanent denominational colleges in Virginia, 1776-1861" (1976). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618791. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-g737-wf49 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a targe round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

State-Wide Pattern of Higher Education in Virginia

DCCUMENT RESUME ED 033 657 HE 001 170 AUTHOF Ccnncr, James R. TTTT.? State-Wide Pattern of Higher Education in Virginia. TnSTTTUTTOV Virginia Higher Education Study Commission, Richmond. Report No Staff Fec-2 Pub Date 65 Note 132g. EDFS Price EDRS Price ME-S0.75 HC-$7.00 Descriptors *Comparative Analysis, Economic Development, Educational. Facilities, *Educational Planning, Enrollment Projections, *Higher Education, *Performance Criteria, Population Trends, *State Standards Identifiers *Virginia Abstract This report discusses higher education in the State of Virginia as it relates to some economic and social factors, and maps the distribution of colleges and universities in the state. A 2% standard, based on the fact that Virginia has 2.2w of the total national population, is used to measure the state's relationship to the US as a whole. In areas of taxation and financial support for schools and colleges, Virginia is significantly below the 2% standard. Its performance in education, which should approximate 2% of national performance, is much lower. The median number of school years completed by the average adult Virginian in 1960 was 9.9, compared to a national average of 10.6; variations among state counties range from 6.5 to 12.8 years of schooling. In 1964, institutions of higher education in Virginia had only 1.54% of all students enrolled in the US. Degree production is low. The greatest deficiency is at the graduate level, where production is less than 1% of national totals, and the rate of increase is slow. Accredited colleges and universities are not well distributed geographically to serve the various local areas of the state. -

Virginia Colleges and Universities

Virginia Colleges and Universities 1 Appalachian SchoolPRIVATE of Law COLLEGESGrundy www.asl.edu 1COMMUNITY Blue Ridge Community College & JUNIORWeyers Cave COLLEG www.brcc.edu ES 1 Christopher NewportPUBLIC University COLLEGESNewport News www.cnu.edu 2 Atlantic University Virginia Beach www.atlanticuniv.edu 2 Central Virginia Community College Lynchburg www.cvcc.vccs.edu 2 College of William and Mary Williamsburg www.wm.edu 3 Averett University Danville www.averett.edu 3 Dabney S. Lancaster Community College Clifton Forge www.dl.vccs.edu 3 George Mason University Fairfax www.gmu.edu 4 Bluefield College Bluefield www.bluefield.edu 4 Danville Community College Danville www.dcc.vccs.edu 4 James Madison University Harrisonburg www.jmu.edu 5 Bridgewater College Bridgewater www.bridgewater.edu 5 Eastern Shore Community College Melfa www.es.vccs.edu 5 Longwood University Farmville www.longwood.edu 6 Catholic Distance University Hamilton www.cdu.edu 6 Germanna Community College Locust Grove www.gcc.vccs.edu 6 Norfolk State University Norfolk www.nsu.edu 7 Christendom College Front Royal www.christendom.edu 7 J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College Richmond www.jsr.vccs.edu 7 Old Dominion University Norfolk www.odu.edu 8 CHRV College of Health Sciences Roanoke 8 John Tyler Community College Chester www.jtcc.edu 8 Radford University Radford www.runet.edu 9 Eastern Mennonite University Harrisonburg www.emu.edu 9 Lord Fairfax Community College Middletown www.lfcc.edu 9 University of Mary Washington Fredericksburg www.umw.edu J Emory and Henry College -

VMI Catalogue 2006-2007

TABLE OF CONTENTS Institute Calendar 2006-2007 ....................................................................................................................... 3 The Institute ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Admissions ...................................................................................................................................................9 Costs And Payment Schedule ................................................................................................................... 15 Financial Aid..............................................................................................................................................17 The Academic Program ............................................................................................................................. 19 The Co-curricular Program.........................................................................................................................25 Reserve Officers Training Corps ................................................................................................................ 35 The Curricula..............................................................................................................................................39 Applied Mathematics Curriculum ........................................................................................................40 Biology Curricula ................................................................................................................................ -

An Almost Unnoticed Quietus Sabbatical Work by Jennifer D

an almost unnoticed quietus sabbatical work by jennifer d. printz Published by the Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University, Roanoke, Virginia. hollins.edu/museum • 540/362-6532 Photography: Ronnie Lee Bailey and Jeff Hofmann Design: Laura Jane Ramsburg This exhibition is sponsored in part by the City of Roanoke through the Roanoke Arts Commission with additional support from Susan Cofer ’64. an almost unnoticed quietus sabbatical work by jennifer d. printz October 5 - December 20, 2017 Eleanor D. Wilson Museum at Hollins University 2 jennifer d. printz interview with jenine culligan, director eleanor d. wilson museum Your work has a contemplative simplicity. Are there artists or art communities that have influenced your work? Elegance and a refined simplicity are something I strive towards in my work. Many of the artists I am most inspired by push their work towards minimalism and in doing so delve into spiritual concepts and concerns. The drawings of Agnes Martin, the lyrical landscapes of Yves Tanguy, and the merging of art and the meditative experience in the work of Mark Rothko are a few that immediately come to mind. I am also influenced by the work of Hilma af Klint and Emma Kunz who were early pioneers in abstraction, which they blended with their own mystical practices. A revelatory moment occurred when I first saw the collection of Tantric paintings collected by French poet Franck André Jamme and published in the book Tantra Song. The paintings are direct descendants of ancient Hindu meditative and mantra practices. Their visual power and history just dumbfounded me as did the egoless practice of making these pieces. -

The Integration of Emory & Henry College

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1996 The integration of Emory & Henry College Scott aD vid Arnold Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Scott aD vid, "The integration of Emory & Henry College" (1996). Master's Theses. Paper 1137. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTEGRATION OF EMORY & HENRY COLLEGE By SCOTT DAVID ARNOLD B.A., Emory & Henry College, 1992 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Richmond in Candidacy for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History May 1996 Richmond, Virginia _....,..-LIBRARY -.. UNJVt!RStTY OF RICHMONO VIRGINIA 23173 1,S)~~ Copyright by Scott D. Arnold 1996 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are numerous people I would like to thank for assisting me in researching and writing my thesis. I should begin by extending my appreciation to all current and former members of the faculty, administration, staff, and alumni of Emory & Henry College who have responded to my inquiries. Their recollections and insights have greatly aided my task. Also, I acknowledge the assistance of various people from the communities surrounding the college who helped me in my research, especially individuals from the Washington County Historical Society. I am particularly grateful to the Emory & Henry College Alumni Office (Monica Hoel, Ellen Price and Sharon Herman) and the library staff of the college who were extremely helpful in locating pertinent people, information, and allowing me access to various school records and documents. -

Comparing Colleges' Graduation Rates

CENTER ON EDUCATION DATA AND POLICY RESEARCH REPORT Comparing Colleges’ Graduation Rates The Importance of Adjusting for Student Characteristics Erica Blom Macy Rainer Matthew Chingos January 2020 ABOUT THE URBAN INSTITUTE The nonprofit Urban Institute is a leading research organization dedicated to developing evidence-based insights that improve people’s lives and strengthen communities. For 50 years, Urban has been the trusted source for rigorous analysis of complex social and economic issues; strategic advice to policymakers, philanthropists, and practitioners; and new, promising ideas that expand opportunities for all. Our work inspires effective decisions that advance fairness and enhance the well-being of people and places. Copyright © January 2020. Urban Institute. Permission is granted for reproduction of this file, with attribution to the Urban Institute. Cover image by Tim Meko. Contents Acknowledgments iv Executive Summary v Adjusted Graduation Rates 1 Appendix A. What Are the Gains from Individual-Level Data? 22 Appendix B. Graduation Rate Tables 25 Notes 28 References 29 About the Authors 30 Statement of Independence 31 Acknowledgments This report was supported by Arnold Ventures. We are grateful to them and to all our funders, who make it possible for Urban to advance its mission. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. Funders do not determine research findings or the insights and recommendations of Urban experts. Further information on the Urban Institute’s funding principles is available at urban.org/fundingprinciples. The authors wish to thank Kelia Washington for excellent research assistance and David Hinson for copyediting.