The Founding of the Permanent Denominational Colleges in Virginia, 1776-1861

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Red Flag Campaign

objectives • Red Flag Campaign development process • Core elements of the campaign • How the campaign uses prevention messages to emphasize and promote healthy dating relationships • Campus implementation ideas prevalence • Women age 16 to 24 experience the highest per capita rate of intimate partner violence. C. Rennison and S. Welchans, “Intimate Partner Violence” U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, May 2000. • In 1 in 5 college dating relationships, one of the partners is being abused. C. Sellers and M. Bromley, “Violent Behavior in College Student Dating Relationships,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice (1996) 1 key players • Advisory committee • College student focus groups development process preliminary focus groups • March 2006, four focus groups held with college students • Two women’s groups; two men’s groups • Students said they were willing to intervene with friends who are being victimized by or acting abusively towards their dates • Students also indicated they would be receptive to hearing intervention and prevention messages from their friends 2 developing core messages • Target college students who are friends/peers of victims and perpetrators of dating violence – Educate friends/peers about ‘red flags’ (warning indicators) of dating violence – Encourage friends/peers to ‘say something’ (intervene in the situation) Social Ecological Model Address norms or customs or people’s experience with local institutions Change in person’s Address influence of knowledge, attitude, peers and intimate behavior partners Address broad social forces, such as inequality, oppression, and broad public policy changes. 3 focus group: example of edits “He told me I was fat and stupid and no one else would want me … … maybe he’s right.” "I told her ‘That’s wrong. -

Patrick Henry

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY PATRICK HENRY: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF HARMONIZED RELIGIOUS TENSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY BY KATIE MARGUERITE KITCHENS LYNCHBURG, VIRGINIA APRIL 1, 2010 Patrick Henry: The Significance of Harmonized Religious Tensions By Katie Marguerite Kitchens, MA Liberty University, 2010 SUPERVISOR: Samuel Smith This study explores the complex religious influences shaping Patrick Henry’s belief system. It is common knowledge that he was an Anglican, yet friendly and cooperative with Virginia Presbyterians. However, historians have yet to go beyond those general categories to the specific strains of Presbyterianism and Anglicanism which Henry uniquely harmonized into a unified belief system. Henry displayed a moderate, Latitudinarian, type of Anglicanism. Unlike many other Founders, his experiences with a specific strain of Presbyterianism confirmed and cooperated with these Anglican commitments. His Presbyterian influences could also be described as moderate, and latitudinarian in a more general sense. These religious strains worked to build a distinct religious outlook characterized by a respect for legitimate authority, whether civil, social, or religious. This study goes further to show the relevance of this distinct religious outlook for understanding Henry’s political stances. Henry’s sometimes seemingly erratic political principles cannot be understood in isolation from the wider context of his religious background. Uniquely harmonized -

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards

Nomination Guidelines for the 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards Full and complete nomination submissions must be received by the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia no later than 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. Please direct questions and comments to: Ms. Ashley Lockhart, Coordinator for Academic Initiatives State Council of Higher Education for Virginia James Monroe Building, 10th floor 101 N. 14th St., Richmond, VA 23219 Telephone: 804-225-2627 Email: [email protected] Sponsored by Dominion Energy VIRGINIA OUTSTANDING FACULTY AWARDS To recognize excellence in teaching, research, and service among the faculties of Virginia’s public and private colleges and universities, the General Assembly, Governor, and State Council of Higher Education for Virginia established the Outstanding Faculty Awards program in 1986. Recipients of these annual awards are selected based upon nominees’ contributions to their students, academic disciplines, institutions, and communities. 2022 OVERVIEW The 2022 Virginia Outstanding Faculty Awards are sponsored by the Dominion Foundation, the philanthropic arm of Dominion. Dominion’s support funds all aspects of the program, from the call for nominations through the award ceremony. The selection process will begin in October; recipients will be notified in early December. Deadline for submission is 5 p.m. on Friday, September 24, 2021. The 2022 Outstanding Faculty Awards event is tentatively scheduled to be held in Richmond sometime in February or March 2022. Further details about the ceremony will be forthcoming. At the 2022 event, at least 12 awardees will be recognized. Included among the awardees will be two recipients recognized as early-career “Rising Stars.” At least one awardee will also be selected in each of four categories based on institutional type: research/doctoral institution, masters/comprehensive institution, baccalaureate institution, and two-year institution. -

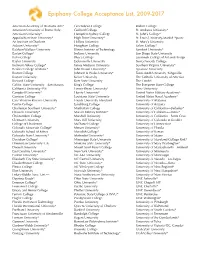

Epiphany Comprehensive College List

Epiphany College Acceptance List, 2009-2017 American Academy of Dramatic Arts* Greensboro College Rollins College American University of Rome (Italy) Guilford College St. Andrews University* American University* Hampden-Sydney College St. John’s College* Appalachian State University* High Point University* St. Louis University-Madrid (Spain) Art Institute of Charlotte Hollins University St. Mary’s University Auburn University* Houghton College Salem College* Baldwin Wallace University Illinois Institute of Technology Samford University* Barton College* Indiana University San Diego State University Bates College Ithaca College Savannah College of Art and Design Baylor University Jacksonville University Sierra Nevada College Belmont Abbey College* James Madison University Southern Virginia University* Berklee College of Music* John Brown University* Syracuse University Boston College Johnson & Wales University* Texas A&M University (Kingsville) Boston University Keiser University The Catholic University of America Brevard College Kent State University The Citadel Califor. State University—San Marcos King’s College The Evergreen State College California University (PA) Lenoir-Rhyne University* Trine University Campbell University* Liberty University* United States Military Academy* Canisius College Louisiana State University United States Naval Academy* Case Western Reserve University Loyola University Maryland University of Alabama Centre College Lynchburg College University of Arizona Charleston Southern University* Manhattan College University -

BAPTISTS in the TYNE VALLEY Contents

BAPTISTS IN THE TYNE VALLEY Paul Revill Original edition produced in 2002 to mark the 350th anniversary of Stocksfield Baptist Church Second revised edition 2009 1 2 BAPTISTS IN THE TYNE VALLEY Contents Introduction 4 Beginnings 5 Recollections: Jill Willett 9 Thomas Tillam 10 Discord and Reconciliation 12 The Angus Family 13 Recollections: Peter and Margaret Goodall 17 Decline 18 A House Church 20 Church Planting 22 New Life 24 Two Notable Ministers 26 New Places for Worship 28 Recollections: George and Betty McKelvie 31 Into the Twentieth Century 32 Post-War Years 37 The 1970s 40 The 1980s and 1990s 42 Into the Present 45 Recollections: Sheena Anderson 46 Onwards... 48 Bibliography & Thanks 51 3 Introduction 2002 marked the 350th anniversary of Stocksfield Baptist Church. There has been a congregation of Christians of a Baptist persuasion meeting in the Tyne Valley since 1652, making it the second oldest such church in the north east of England and one of the oldest surviving Baptist churches in the country. However, statistics such as this do not really give the full picture, for a church is not primarily an institution or an organisation, but a community of people who have chosen to serve and worship God together. The real story of Stocksfield Baptist Church is told in the lives of the men and women who for three and a half centuries have encountered God, experienced his love and become followers of Jesus Christ, expressing this new-found faith through believers’ baptism. They have given their lives to serving their Lord through sharing their faith and helping people in need, meeting together for worship and teaching. -

The Minister's Son a Record of His Achievements

THE MINISTER'S SON A RECORD OF HIS ACHIEVEMENTS By Clarence Edward Noble Macartney n Minister of The Arch Street Presbyterian Church Philadelphia, Pennsylvania EAKINS, PALMER & HARRAR PHILADELPHIA Copyright, 1917 by Eakina, Palmer & Harrar Philadelphia To WOODROW WILSON Son of a Presbyterian Minister Spokesman for the Soul of America THE MINISTER'S SON THE MINISTER'S SON FEW summers ago, engaged in historical research in the Shenandoah Valley, that star-lit and mountain-walled abbey of the Confederacy, I went to call at the home of the venerable Dr. Graham, pastor emeritus of the Presbyterian Church at Winchester, Vir ginia. It was in his home that "Stonewall" Jackson lived when stationed in the Shenan doah Valley. I remember him saying of Jackson that before all else he was a Christian. That was the first business of his life; after that, a soldier. I spent an interesting hour with that delightful old man as he made men tion of leading personalities before, since, and at the time of the Civil War. When he learned that I had studied at Princeton, he spoke of Woodrow Wilson, then being mentioned as a candidate for the Governorship of New Jersey. He had known his father, the Reverend Joseph R. Wilson, D. D., intimately, and to his memory he paid this tribute: "Take him all in all, of all the good and great men I have known in my long life, he was the best." 7 Tl»e The son of that Presbyterian minister was, s!^i8ter'S 0n the 4th of March' inaugurated for the second time as President of the United States, having been re-elected to that office by the most remarkable popular approval ever given to any candidate, and that in spite of a cam paign of vituperation and abuse unprecedented in the history of the nation. -

Princeton College During the Eighteenth Century

PRINCETON COLLEGE DURING THE Eighteenth Century. BY SAMUEL DAVIES ALEXANDER, AN ALUMNUS. NEW YORK: ANSON D. F. RANDOLPH & COMPANY, 770 Broadway, cor. 9th Street. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by ANSON D. F. RANDOLPH & CO., In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. •^^^ill^«^ %tVYO?^ < I 1 c<\' ' ' lie \)^'\(^tO\.y>^ ^vn^r^ J rjA/\^ \j ^a^^^^ c/^^^^^y^ ^ A^^ 2^^^ ^ >2V^ \3^ TrWxcet INTRODUCTORY NOTE. On account of the many sources from which I have derived my in- formation, and not wishing to burden my page with foot-notes, I have omitted all authorities. 1 have drawn from printed books, from old news- papers and periodicals, and from family records, and when the words of another have suited me, 1 have used them as my own. As Dr. Allen " licensed says, Compilers seem to be pillagers. Like the youth of Sparta, they may lay their hands upon plunder without a crime, if they will but seize it with adroitness." Allen's Biographical Dictionary, Sprague's Annals, and Duyckinck's of American have been of the service Cyclopaedia Literature, greatest ; but in many instances I have gone to the original sources from which they derived their information. I have also used freely the Centennial Discourses of Professors Giger and Cameron of the College. The book does not profess to be a perfect exhibition of the graduates. But it is a beginning that may be carried nearer to perfection in every succeeding year. Its very imperfection may lead to the discovery of new matter, and the correction of errors which must unavoidably be many. -

Emory and Henry College 01/30/1989

VLR Listed: 1/18/1983 NPS Form 10-900 NRHP Listed: 1/30/1989 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Eip. 10-31-84 United States Department of the interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Piaces received OCT 1 ( I935 Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Emory and Henry College (VHLD File No. 95-98) and or common Same 2. Location street & number VA State Route 609 n/a not for publication Emory city, town X vicinity of 51 state Virginia ^^^^ Washington code county 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment -X religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation n/a no military other: 4. Owner of Property name The Holston Conference Colleges Board of Trustees, c/o Dr. Heisse Johnson street & number P.O. Box 1176 city,town Johnson City n/-a vicinity of state Tennessee 37601 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Washington County Courthouse street&number Main Street city.town Abingdon state Virginia 24210 6. Representation in Existing Surveys titieyirginia Historic Landmarks has this property been determined eligible? yes X no Division Survey File No. 95-98 date 1982 federal X_ state county local depository tor survey records Virginia Historic Landmarks divi sion - 221 Governor Street cuv.town Richmond state Virginia 23219 7. -

How English Baptists Changed the Early Modern Toleration Debate

RADICALLY [IN]TOLERANT: HOW ENGLISH BAPTISTS CHANGED THE EARLY MODERN TOLERATION DEBATE Caleb Morell Dr. Amy Leonard Dr. Jo Ann Moran Cruz This research was undertaken under the auspices of Georgetown University and was submitted in partial fulfillment for Honors in History at Georgetown University. MAY 2016 I give permission to Lauinger Library to make this thesis available to the public. ABSTRACT The argument of this thesis is that the contrasting visions of church, state, and religious toleration among the Presbyterians, Independents, and Baptists in seventeenth-century England, can best be explained only in terms of their differences over Covenant Theology. That is, their disagreements on the ecclesiological and political levels were rooted in more fundamental disagreements over the nature of and relationship between the biblical covenants. The Baptists developed a Covenant Theology that diverged from the dominant Reformed model of the time in order to justify their practice of believer’s baptism. This precluded the possibility of a national church by making baptism, upon profession of faith, the chief pre- requisite for inclusion in the covenant community of the church. Church membership would be conferred not upon birth but re-birth, thereby severing the links between infant baptism, church membership, and the nation. Furthermore, Baptist Covenant Theology undermined the dominating arguments for state-sponsored religious persecution, which relied upon Old Testament precedents and the laws given to kings of Israel. These practices, the Baptists argued, solely applied to Israel in the Old Testament in a unique way that was not applicable to any other nation. Rather in the New Testament age, Christ has willed for his kingdom to go forth not by the power of the sword but through the preaching of the Word. -

The History of the Baptists of Tennessee

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 6-1941 The History of the Baptists of Tennessee Lawrence Edwards University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Edwards, Lawrence, "The History of the Baptists of Tennessee. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1941. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2980 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Lawrence Edwards entitled "The History of the Baptists of Tennessee." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. Stanley Folmsbee, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: J. B. Sanders, J. Healey Hoffmann Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) August 2, 1940 To the Committee on Graduat e Study : I am submitting to you a thesis wr itten by Lawrenc e Edwards entitled "The History of the Bapt ists of Tenne ssee with Partioular Attent ion to the Primitive Bapt ists of East Tenne ssee." I recommend that it be accepted for nine qu arter hours credit in partial fulfillment of the require ments for the degree of Ka ster of Art s, with a major in Hi story. -

The Future of Southern Baptists As Evangelicals

The Future of Southern Baptists as Evangelicals by Steve W. Lemke Provost, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary for the Maintaining Baptist Distinctives Conference Mid-America Baptist Theological Seminary April 2005 Introduction What is the future of Southern Baptists as evangelical Christians? In order to address adequately my assigned topic, I must attempt to answer two questions. First, do Southern Baptists have a future? And second, what future do Southern Baptists have as evangelicals? However, because Southern Baptists have been increasingly engaged in the evangelical world, these two questions are bound inextricably together. I believe that the major issues that will help shape the future of the Southern Baptist Convention arise in large measure from our interface with other evangelical Christian groups over the past few decades. In this presentation, I’ll be suggesting six issues that I believe will play a large role in the future shape of the Southern Baptist Convention. After I describe why I think these issues are so important to the future of Southern Baptist life, I’ll make a prediction or warning about how I’m guessing Southern Baptists will address these issues in the next couple of decades unless something changes dramatically. Let me begin with a few caveats. First, my purpose: I offer this talk as neither a sermon nor as a typical research paper, but my purpose is primarily to spur discussion and dialogue as we seek to address these issues together. Perhaps these ruminations will spark or provoke a helpful dialogue afterward. Second, the spirit with I which present this paper: I am writing from an unapologetically Southern Baptist perspective. -

The Baptist Tradition and Religious Freedom: Recent Trajectories

THE BAPTIST TRADITION AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM: RECENT TRAJECTORIES by Samuel Kyle Brassell A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnel Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2019 Approved by _______________________________ Advisor: Professor Sarah Moses _______________________________ Reader: Professor Amy McDowell _______________________________ Reader: Professor Steven Skultety ii © 2019 Samuel Kyle Brassell ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College for providing funding to travel to the Society of Christian Ethics conference in Louisville to attend presentations and meet scholars to assist with my research. iii ABSTRACT SAMUEL KYLE BRASSELL: The Baptist Tradition and Religious Freedom: Recent Trajectories For my thesis, I have focused on the recent religious freedom bill passed in Mississippi and the arguments and influences Southern Baptists have had on the bill. I used the list of resolutions passed by the Southern Baptist Convention to trace the history and development of Southern Baptist thought on the subject of religious freedom. I consulted outside scholarly works to examine the history of the Baptist tradition and how that history has influenced modern day arguments. I compared these texts to the wording of the Mississippi bill. After conducting this research, I found that the Southern Baptist tradition and ethical thought are reflected in the wording of the Mississippi bill. I found that the large percentage of the Mississippi population comprised of Southern Baptists holds a large amount of political power in the state, and this power was used to pass a law reflecting their ethical positions.