Retrieved from Discoverarchive, Vanderbilt University's Institutional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Career Services Annual Report 2015 – 2016

CAREER SERVICES ANNUAL REPORT 2015 – 2016 2015 – 2016 GOALS CAREER SERVICES 1. Conduct five on-campus career fairs and one combined career fair as part of the Nashville Area Career Fairs Consortium. 2. Continue outreach efforts to first-year students to increase awareness of office services and programs by 5% as measured by the new “Freshman Friendly” initiative at career fairs, tracking number of visits by freshmen to our office as well as tabulating log-in rates to TechWorks and other Career Services on-line resources. 3. Increase overall student participation in TechWorks database by 10%. 4. Increase student enrollment in the Experiential Education program by 5% through expanding cooperative education and internship opportunities for our students. 5. Establish an advisory board composed of members from each school and college, as well as industry professionals. Page 1 2015 – 2016 GOALS CAREER SERVICES 1. Conduct five on-campus career fairs and one combined career fair as part of the Nashville Area Career Fairs Consortium. ON-CAMPUS CAREER FAIR TOTALS: 381 EMPLOYERS AND 4,028 ATTENDEES • CAREER DAY 2015 – 128 registered employers, 1,854 attendees – 7.3% increase • ENGINEERING FAIR 2016 – 133 registered employers, 1,306 attendees – 30% increase • HEALTHCARE FAIR 2016 – 21 registered employers, 160 attendees – 6.7% increase • EDUCATION FAIR 2016 – 41 registered employers, 306 attendees – 12.8% decrease • SPRING FAIR 2016 – 58 registered employers, 402 attendees – 16.9% increase ATTENDANCE: • NASHVILLE AREA COLLEGE TO CAREER FAIR AND TEACHER RECRUITMENT FAIR 2016 – 316 employers – 915 attendees (130 from TTU) – 39% decrease. NOTE: this event is held in collaboration with 12 other universities: Athens State, Austin Peay State, Aquinas College, Belmont University, Cumberland University, Fisk University, Lipscomb University, Martin Methodist College, Middle Tennessee State University, Tennessee State University, Trevecca Nazarene University, and Vanderbilt University. -

Revisions to Teacher Prep Review Press Statement Final

March&2,&2015& & Contact:&Lisa&Cohen& & & Phone:&(310)&395:2595& & & [email protected]& & REVISED&TEACHER&PREP&PROGRAM&RANKINGS&ISSUED&BY&NCTQ& ! March&2,&2015&(Washington,&DC)&–&The&National&Council&on&Teacher&Quality&today&announced&revisions& to&the&rankings&published&in&last&year’s!edition&of&the&Teacher!Prep!Review,!a&comprehensive&evaluation& of&the&programs&that&prepare&the&vast&majority&of&the&nation’s&teachers.&& 123&program&scores&on&NCTQ’s&standards&were&revised.&106&of&these&changes&were&made&because& programs&provided&new&materials;&the&remaining&17&changes&were&a&result&of&errors&in&NCTQ’s&original& analysis.&NCTQ&changed&the&rankings&of&64&programs&offered&by&38&providers&(each&provider&can&offer& multiple&programs).& The&changes&resulted&from&an&appeals&process&NCTQ&launched&last&summer&to&investigate&and&address& possible&errors&in&the&2014&Teacher!Prep!Review.&NCTQ&asked&the&1,202&providers&(both&institutions&of& higher&education&and&alternative&certification&providers)&in&its&sample&to&look&over&its&findings&about& their&programs.&If&providers&identified&suspected&errors,&they&could&submit&supporting&documentation& for&NCTQ&to&review.& Because&the&next&edition&of&the&Teacher!Prep!Review!will¬&be&published&until&October&2016,&programs& were&also&able&to&submit&new&materials&that&could&reflect&changes&programs&have&made&since&being& initially&reviewed.&& NCTQ&employed&88&staff,&analysts&and&experts&to&examine&almost&1,000&textbooks&and&22,000& documents&in&order&to&generate&the&19,000&ratings&that&went&into&the&Teacher!Prep!Review.!NCTQ&is& -

Fall 2015 Graduate School Fair Oglethorpe University Turner Lynch Campus Center October 12, 2015 - 6 – 8Pm

Fall 2015 Graduate School Fair Oglethorpe University Turner Lynch Campus Center October 12, 2015 - 6 – 8pm Presented by: Oglethorpe University Professional Development Atlanta Laboratory for Learning Agnes Scott College Office of Internship and Career Development 1 List of Graduate School Programs & Services Page Business/Management/ Economics 3 Education 4 Fine Arts & Design 6 Humanities 6 Human Resources/Public Administration & Policy 7 Law/Criminal Justice 8 Psychology/Health/Medicine 9 Religious Studies/Theology 14 Social Work 14 STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Math) 15 Universities with a Variety of Graduate Programs 16 Graduate School Services 16 2 Business/Management/Economics Albany State University, Albany, Georgia Program: Business Administration Albany State is a state-supported, historically black university. Our MBA program offers concentrations in Accounting, Health Care Management, and Supply Chain & Logistics Management. Brenau University, Gainesville, Georgia Programs: Business Administration, Organizational Leadership Brenau University is a private, not-for-profit, undergraduate- and graduate-level higher education institution with multiple campuses and online programs. With one course at a time, one night a week or online, Brenau University’s AGS programs are designed with you in mind. Columbus State University, Columbus, Georgia Programs: Business Administration, Organizational Leadership The Turner College of Business and the TSYS School of Computer Science at Columbus State University are housed in the Center for Commerce and Technology (CCT). Turner boasts 8 graduate programs, numerous certifications and a variety of student organizations including: Accounting Club, CSU American Marketing Association, Financial Investments Association, Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) and Campus Nerds. -

Tennessee Promise Institutions

TENNESSEE PROMISE INSTITUTIONS TENNESSEE COLLEGES OF APPLIED TECHNOLOGY (TCATs) Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Athens Tennessee College of Applied Technology- McMinnville Athens, TN McMinnville, TN www.tcatathens.edu www.tcatmcminnville.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Chattanooga Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Memphis Chattanooga, TN Memphis, TN www.chattanoogastate.edu/tcat www.tcatmemphis.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Covington Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Morristown Covington, TN Morristown, TN www.tcatcovington.edu www.tcatmorristown.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Crossville Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Murfreesboro Crossville, TN Murfreesboro, TN www.tcatcrossville.edu www.tcatmurfreesboro.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Crump Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Nashville Crump, TN Nashville, TN www.tcatcrump.edu www.tcatnashville.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Dickson Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Newbern Dickson, TN Newbern, TN www.tcatdickson.edu www.tcatnewbern.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Elizabethton Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Oneida/Huntsville Elizabethton, TN Huntsville, TN www.tcatelizabethton.edu www.tcatoneida.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Harriman Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Paris Harriman, TN Paris, TN www.tcatharriman.edu www.tcatparis.edu Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Hartsville Tennessee College of Applied Technology- Pulaski -

Westmoreland Elementary School Professional Directory

Westmoreland Elementary School Professional Directory Administration B.S., 2005, Western Kentucky University David E. Stafford (2008) PRINCIPAL (WHS) A.S., 1998, Volunteer State Community College Second Grade B.S., 2000, Middle Tennessee State University Mindy Haskins (2016) M.Ed., 2003, Tennessee State University A.S., 2010, Volunteer State Community College Ed.S., 2004, Tennessee State University B.S., 2012, Tennessee State University Ed.D., 2007, Tennessee State University Lindsey Jones (2016) Instructional Coaching Certificate, 2019, A.S., 2009, Volunteer State Community College Lipscomb University B.S., 2011, Tennessee Tech University Katie Racki (2014) CHAIR Lead Educator A.S., 2012, Volunteer State Community College Amy Rogers (2018) (WHS) B.S., 2014, Tennessee State University B.S., 2008, Tennessee State University Alicia Perry (2018) M.Ed., 2012, Union University B.S., 2018, Tennessee State University Instructional Coaching Certificate, 2019, Paula Hannah (2019) Lipscomb University B.S., 2002, Austin Peay State University M.Ed., 2011, Arkansas State University Counseling Marisa Whittemore (2021) B.S., 2018, Tennessee Tech University Third Grade M.Ed., 2021, Tennessee Tech University Natalie Anderson (2018) B.S., 2018, Trevecca Nazarene University Pre-K M.Ed., 2020, Capella University Skye M. Rainwater (2021) Kacie Baldwin (2014) CHAIR B.S., 2015, The University of Tennessee at B.S., 2014, Western Kentucky University Chattanooga M.A., 2017, Cumberland University Ed.S., 2020, Arkansas State University Kindergarten Kelsey Kittrell -

Stephen D. 'Steve' Rygiel Birmingham AIDS Outreach 205 32

Stephen D. ‘Steve’ Rygiel Birmingham AIDS Outreach 205 32nd Street South Birmingham, AL 35233 (205)427-4795 [email protected] Steve received a Bachelor of Science degree in Microbiology and a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from Auburn University. At Auburn, Steve was involved in the college Honors Program, named Sophomore Chemistry Student of the Year and Mortar Board Senior English Student of the Year. Steve then completed two years of graduate coursework in Molecular and Cellular Pathology from the University of Alabama-Birmingham. He performed five laboratory rotations studying biochemical disease mechanisms in the following areas: 1) cardiovascular disease due to environmental stressors such as environmental tobacco smoke, 2) neurodegenerative disease processes and apoptosis, 3) upper gastrointestinal tract diseases and microfloral equilibrium, 4) inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal mucosa and mucosal immunity, and 5) metastatic breast tissue diseases and biologic markers of cancer. Steve then received his Master of Arts degree in English at Auburn University. Receiving his Juris Doctor at Cumberland School of Law, Steve was involved in the Community Service Organization as vice president of Service and vice president of Public Interest. He was a 1L Representative, member of Cordell Hull Speakers Forum, received the Cumberland Spirit of Service Recognition for Volunteerism, and was a volunteer for Habitat for Humanity, Hands on Birmingham, Lakeshore Foundation, and the ‘Street Law’ program. As the director of Aiding Alabama Legal Program and client attorney at Birmingham AIDS Outreach, Steve has provided pro bono legal services to over 600 individuals living with HIV-AIDS in Alabama in a five-year period. -

2019-2020 Law School Catalog

Law School Catalog 2019/2020Catalog Vanderbilt University 2019/2020 School Archived Law Containing general information and courses of study for the 2019/2020 session corrected to July 2019 Nashville The university reserves the right, through its established procedures, to2019/2020 modify the requirementsCatalog for admission and graduation and to change other rules, regulations, and provisions, including those stated in this bulletin and other publications, and to refuse admission to any student, or to require the with- drawal of a student if it is determined to be in the interest of the student or the university. All students, full time or part time, who are enrolled in Vanderbilt courses are subject to the same policies. Policies concerning noncurricular matters and concerning withdrawal for medical or emotional reasons can be found in the Student Handbook, which is on the Vanderbilt website at vanderbilt.edu/student_handbook. School NONDISCRIMINATION STATEMENT In compliance with federal law, including the provisions of Title VI and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendment of 1972, Sections 503 and 504 of the RehabilitationArchived Act of 1973, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990,the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, Executive Order 11246, the Vietnam Era Veterans Readjustment Assistance Act of 1974 as amended by the Jobs for Veterans Act, and the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act, as amended, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008, Vanderbilt University does not discriminate against individuals on theLaw basis of their race, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, military service, covered veterans status, or genetic information in its administration of educational policies, programs, or activities; admissions policies; scholarship and loan programs; athletic or other university-administered programs; or employment. -

William M. Lawrence

William M. Lawrence Counsel | Birmingham, AL T: 205-458-5425 [email protected] Legal Secretary Michelle Prestley (205) 458-5495 [email protected] Services Corporate, Mergers & Acquisitions, Commercial Contracts, Business Formation, Corporate Governance & Shareholder Disputes, William M. "Bill" Lawrence is a member of the firm's Corporate practice group and focuses his practice in the areas of corporate and business transaction law and wireless telecommunications law. Bill’s business practice focuses generally on the representation of private and closely held companies, mergers and acquisitions, the formation and governance of various business organizations, e-commerce/technology acquisitions and agreements, and a wide range of other commercial contract matters. Bill has a wireless telecommunications practice, which focuses on representing wireless carriers, cell tower owners, wireless network infrastructure providers, and other mobile broadband industry businesses in a broad range of legal, regulatory, and business related issues, including site and right- of-way space acquisitions for cell towers, small cell facilities, and other communications facilities (whether through leasing, licensing, purchasing, or obtaining other interests), communications facility and infrastructure deployments and upgrades, and network and infrastructure asset sales and other divestitures, in connection with, among other areas, site acquisition and deployment of macro sites (including cell towers, rooftop installations, etc.) and small cell deployments, -

Elizabeth Burch Vita

Updated: March 25, 2013 Elizabeth Chamblee Burch University of Georgia School of Law 225 Herty Drive Athens, Georgia 30602 E-mail: [email protected] Office: 706.542.5203; Cell: 205.994.0375 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS____________________________________________________________ University of Georgia School of Law Athens, Georgia Associate Professor of Law May 2011-present Courses: Complex Litigation, Mass Torts, Civil Procedure Florida State University College of Law Tallahassee, Florida Assistant Professor of Law May 2008-May 2011 Courses: Complex Litigation, Civil Procedure, Evidence Honors: University Graduate Teaching Award Recipient, 2011 Tenure awarded, 2011 Voted “Professor of the Year” by Florida State’s second and third year students, 2010 Cumberland School of Law, Samford University Birmingham, Alabama Assistant Professor of Law May 2006-May 2008 Courses: Complex Litigation, Civil Procedure I, Civil Procedure II, Law and Literature Honors: Harvey S. Jackson Excellence in Teaching Award, 2008 Lightfoot, Franklin & White Faculty Scholarship Award, 2008 PUBLICATIONS______________________________________________________________________ Books: • THE LAW OF CLASS ACTIONS AND OTHER AGGREGATE LITIGATION (2d Ed., Foundation Press, forthcoming, 2013) (with Richard Nagareda, Robert G. Bone, Charles Silver, and Patrick Woolley) Articles: • Adequately Representing Groups, 81 FORDHAM LAW REVIEW (forthcoming 2013) (symposium) • Disaggregating, 90 WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW (forthcoming, 2013) (symposium) • Financiers as Monitors in Aggregate Litigation, -

2019-2020 Academic Catalog

2019-2020 Academic Catalog Academic Catalog 2019-2020 Accreditation Tennessee Wesleyan University is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges to award baccalaureate and masters degrees. Contact the Commission on Colleges at 1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097 or call 404-679-4500 for questions about the accreditation of Tennessee Wesleyan University. In addition, Tennessee Wesleyan’s programs have been approved by: The Tennessee State Board of Education The University Senate of the United Methodist Church This catalog presents the program requirements and regulations of Tennessee Wesleyan University in effect at the time of publication. Students enrolling in the University are subject to the provisions stated herein. Statements regarding programs, courses, fees, and conditions are subject to change without advance notice. Tennessee Wesleyan University was founded in 1857. Tennessee Wesleyan University is a comprehensive institution affiliated with theHolston Conference of the United Methodist Church. Tennessee Wesleyan University adheres to the principles of equal education, employment opportunity and participation in collegiate activities without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital or family status, disability or sexual orientation. This policy extends to all programs and activities supported by the University. 3 Table of Contents Academic Calendar 6 Merner-Pfeiffer Library 45 Mission/Purpose 9 Student Success Center 45 Definition of a Church Related -

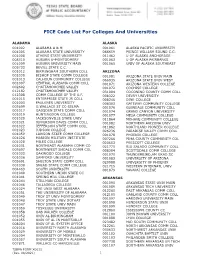

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Wesley M. Walker

Wesley M. Walker Associate PRACTICE EMPHASIS: Litigation: Commercial, Construction, Employment EDUCATION: J.D., cum laude, Cumberland School of Law, 2018 Associate Editor, Cumberland Law Review Vols. 47 & 48, Judge James Edwin Horton Inn of Court, Caruthers Fellow, Cordell Hull Speaker’s Forum President B.A., magna cum laude, University of Alabama, 2014 Presidential Scholar ADMITTED: Email: [email protected] State Bar of Texas Phone: (713) 351-0336 Fax: (713) 850-4211 COURT ADMISSIONS: U.S. District Court, Northern, Southern, Eastern and Western Districts of Texas Profile: Wesley Walker’s practice focuses on both construction litigation and alternative dispute resolution, in which he represents general contractors, subcontractors, suppliers and owners in a variety of construction related disputes, as well as labor and employment litigation. Prior to joining the firm, Wesley was an associate in a large, national law firm recognized in the area of insurance defense, where he was a member of the complex tort and general casualty practice group. While at his previous frim, Wesley frequently represented a national rideshare entity along with several construction and energy clients. Additionally, Wesley evaluated ERISA and non-ERISA disputes over disability, life and health coverage for the insurance industry and self-funded plans. Representative Experience: • Represented national rideshare entity in matters of liability frequently exceeding $500,000 and up to $1 million • Represented major insurer in first-party actions emanating from coverage disputes • Represented construction and energy clients in matters of alleged “on the job” and premises liability injuries • Represented policy carriers in ERISA and non-ERISA disputes originating from denials of benefits Affiliations: State Bar of Texas, Construction and Employment Law Sections Houston Bar Association, Construction and Employment Law Sections Houston Young Lawyers Association 5/7/2020 122 .