Autism, Conceptual Metaphor, and the Autistic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 14/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 14/12 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 318 - August 2012 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 14/12 (Nr. 318) August 2012 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Mit ein paar Impressionen von der Premiere des Kinofilms DIE KIR- CHE BLEIBT IM DORF, zu der wir am vergangenen Mittwoch ein- geladen waren, möchten wir uns in den Sommerurlaub verabschieden. S ist wie fast jedes Jahr: erst wenn alle Anderen ihren Urlaub schon absolviert haben, sind wir dran. Aber so ein richtiger Urlaub ist das eigentlich gar nicht. Nichts von we- gen faul am Strand liegen und sich Filme in HD auf dem Smartphone reinziehen! Das Fantasy Filmfest Fotos (c) 2012 by Wolfram Hannemann steht bereits vor der Tür und wird uns wieder eine ganze Woche lang von morgens bis spät in die Nacht hinein mit aktueller Filmware ver- sorgen. Wie immer werden wir be- müht sein, möglichst viele der prä- sentierten Filme auch tatsächlich zu sehen. Schließlich wird eine Groß- zahl der Produktionen bereits kurze Zeit nach Ende des Festivals auf DVD und BD verfügbar sein. Und da möchte man natürlich schon vor- her wissen, ob sich ein Kauf lohnen wird. Nach unserer Sommerpause werden wir in einem der Newsletter wieder ein Resümee des Festivals ziehen. Es wird sich also lohnen weiter am Ball zu blei- ben. Ab Montag, den 17. -

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

Terra Nova, an Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience

Syracuse University SURFACE S.I. Newhouse School of Public Media Studies - Theses Communications 8-2012 Terra Nova, An Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Terra Nova, An Experiment in Creating Cult Televison for a Mass Audience" (2012). Media Studies - Theses. 5. https://surface.syr.edu/ms_thesis/5 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies - Theses by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When it aired in Fall 2011 on Fox, Terra Nova was an experiment in creating a cult television program that appealed to a mass audience. This thesis is a case study of that experiment. I conclude that the show failed because of its attempts to maintain the sophistication, complexity and innovative nature of the cult genre while simultaneously employing an overly simplistic narrative structure that resembles that of mass audience programming. Terra Nova was unique in its transmedia approach to marketing and storytelling, its advanced special effects, and its dystopian speculative fiction premise. Terra Nova’s narrative, on the other hand, presented a nostalgically simple moralistic landscape that upheld old-fashioned ideologies and felt oddly retro to the modern SF TV audience. Terra Nova’s failure suggests that a cult show made for this type of broad audience is impossible. -

Andrew Conder Acs

ANDREW CONDER ACS. SOC Cinematographer Camera Operator Steadicam Owner / Operator Mobile: 0411260476 Email: [email protected] Feature Films and T.V. Series 2018 “The End” Season 1 (TV) SeeSaw Films / Foxtel/ Sky UK Camera Operator Directors: Jessica M. Thomson / Jonathon Steadicam Operator Brough D.P: Garry Phillips ACS "Occupation - Rainfall" (F) Quirky Mama Productions Camera Operator Directors: Luke Sparke Steadicam Operator D.P: Tony O’Loughlan “Wanted” Season 3 (TV) Matchbox Pictures Camera Operator Directors: Peter Templeman, Jocelyn Steadicam Operator Moorhouse D.P: Mark Wareham ACS “The Family Law” Season 3 (TV) Matchbox Pictures Camera Operator Directors: Ben Chessell, Sophie Miller Steadicam Operator D.P: Aaron McLisky 2017 “The Bureau of Magical Things” (TV) Jonathan M. Shiff Productions Main Unit D.P Directors: Grant Brown, Evan Clarry Camera Operator “Picnic at Hanging Rock” (TV) Fremantlemedia Australia Camera Operator Directors: Larysa Kondracki, Michael Rymer Steadicam Operator D.P: Garry Phillips ACS “Stage Mums” Series 3 (Web / TV) Sunday Arvo Productions Main Unit D.P Director: Louise Alston Camera Operator 2016 ABC TV "Blue Water Empire" (TV) Director: Steven McGregor Main Unit D.P Camera Operator "Nowhere Boys 3" (TV) Matchbox Pictures Camera Operator Directors: Rowan Woods, Sian Davies, Nick Verso Steadicam Operator D.P: Craig Barden ACS 2015 "The Shallows" (F) Vengeance Productions Pty Ltd Camera Operator Director: Jaume Collet-Serra Steadicam Operator D.P: Flavio Labiano Main Unit D.P "Boar" (F) Pig Enterprises -

Bc. Vendula Kreplová

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA ÚSTAV FILMU A AUDIOVIZUÁLNÍ KULTURY BC. VENDULA KREPLOVÁ (FAV, magisterské prezenční studium) Daredevil: Podoba klasického vyprávění v superhrdinském seriálu Netflixu Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Radomír D. Kokeš, Ph.D. Brno 2018 Prohlášení o samostatnosti: Prohlašuji, že jsem pracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených zdrojů. V Brně dne 29. 01. 2018 Podpis: ............................................................... Vendula Kreplová Poděkování: Na tomto místě bych ráda chtěla poděkovat vedoucímu práce, Mgr. Radomíru D. Kokešovi, Ph.D., za pečlivé vedení, nezměrnou trpělivost a cenné připomínky k dané problematice. Rovněž bych chtěla poděkovat své rodině za trpělivost a nemalou duševní podporu poskytnutou během psaní této práce. Obsah 1. Úvod 5 2. Teoreticko-metodologická část 10 2.1 Teoretická východiska výzkumu 10 2.2 Výzkumná praxe 14 3. Struktura první série 17 4. Výstavba hrdiny a antagonisty 19 4.1 Výstavba hrdiny 19 4.1.1 Náboženství 24 4.2 Výstavba antagonisty 26 5. Detektivní linie 33 6. Logika flashbacků 40 7. Propojení s MCU a ostatními seriály 46 8. Binge watching a simultánní vysílání 56 9. Závěr 60 10. Bibliografie 63 10.1.1 Citovaná a konzultovaná 63 literatura 10.1.2 Webové stránky 68 10.2.1 Analyzovaný seriál 68 10.2.2 Citované filmy a seriály 69 10. Summary 73 1. ÚVOD V roce 2015 byla uvedena první série seriálu Daredevil (2015-?), který se nechává inspirovat komiksovými příběhy stejnojmenného superhrdiny, Daredevila/Matta Murdocka. Seriál uvedla stanice Netflix a představila ho jako první z řady několika seriálů pracujících s hrdiny známými z komiksů vydávanými pod značkou nakladatelství Marvel. Po uvedení Daredevila následovaly další superhrdinské hrané seriály: Jessica Jones (2015-?), Luke Cage (2016-?), Iron Fist (2017-?) a konečně týmový seriál Marvel’s Defenders (2017-?), v němž se všichni čtyři výše zmínění hrdinové setkali. -

Film and Video Labelling Body (Home Media) August 2016

Film and Video Labelling Body (Home Media) August 2016 10,000 Days Eric Small 87.22 25/08/2016 M Violence DVD 100 Years Of Air Combat A Century Of Epic Air Battles Roger Ulanoff 983.56 25/08/2016 PG War footage DVD 100 Years Of British Transport (100 Years of: British Not Stated 231.41 30/08/2016 G DVD Ships, British Buses, British Trains, British Trams) 11.22.63 James Strong, John David Coles, 418.32 3/08/2016 R16 Violence, sexual references & DVD James Franco offensive language 11.22.63 James Strong, John David Coles, 436.2 3/08/2016 R16 Violence, sexual references & Bluray James Franco offensive language 11.22.63 (Disc 1) Kevin MacDonald, Frederick E.O. 225.11 1/08/2016 R16 Violence, sexual references & DVD Toye, James Strong offensive language 11.22.63 (Disc 2) James Franco, John David Coles 193.17 1/08/2016 R16 Violence, sexual references & DVD et al. offensive language 21 Jump Street/22 Jump Street Phil Lord/Christopher Miller 443.06 15/08/2016 R16 Violence, offensive language, drug Bluray (2 use, sex scenes & sexual material Disc)/UV 30 Minutes or Less Ruben Fleischer 79.34 1/08/2016 R16 Violence,sex scenes and content that DVD may disturb 5 Days of War Renny Harlin 108.25 5/08/2016 R16 Violence and offensive language DVD 5 Days of War Renny Harlin 113.02 16/08/2016 R16 Violence and offensive language Bluray 5th Dimension - Secrets of the Supernatural Christian Frey/Thomas Zintl et al 300.41 30/08/2016 M DVD (3 Disc) Aaahh!!! Real Monsters Collector's Edition Jim Duffy 1227 9/08/2016 G DVD Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter/Night Watch/Day -

Hassan Johnson Resume

Hassan Johnson SAG / AFTRA TELEVISION The Black List Guest Star NBC/ Dir. Michael Watkins Person of Interest Guest Star CBS/ Dir. Richard J Lewis The Good Wife Guest Star CBS/ Dir. Fred Toye Cold Case Guest Star CBS/ Dir. Jeannot Szwarc Dark Blue Guest Star TNT/ Dir. Karen Gaviola Law & Order: SVU Guest Star NBC/ Dir. David Platt Numbers Guest Star CBS/ Dir. Michael Watkins Entourage Guest Star HBO/ Dir. Julian Farino Rescue Me Guest Star FX / Dir. John Fortenberry ER Recurring NBC/ Various Law & Order Guest Star NBC/ Dir. Constantine Makris The Wire Recurring HBO / Various NYPD Blue Guest Star ABC / Dir. Steven DePaul New York Undercover Guest Star FOX / Dir. Melanie Mayron FILM Staten Island Summer Supporting Dir. Rhys Thomas Top Five Supporting Dir. Chris Rock A Talent for Trouble Lead Dir. Marvis Johnson Gun Supporting Dir. Jessy Terrero Brooklyn’s Finest Supporting Dir. Antoine Fuqua Marci X Supporting Dir. Richard Benjamin Paid in Full Supporting Dir. Chuck Stone Prison Song Supporting Dir. Darnell Martin In Too Deep Supporting Dir. Michael Rymer Black & White Supporting Dir. James Toback Belly Supporting Dir. Hype Williams Devil’s Own Supporting Dir. Alan Pakula Clockers Supporting Dir. Spike Lee SPECIAL SKILLS Billiards/Pool Player, Boxer, Football, Ice Skating, Running – sprint, Scuba Diving, Swimming – ability – general, Weight Lifting, Voiceover, African Accent, New York Accent, Puerto Rican Accent, Southern Accent, West Indian Accent AGENT: Brianna Ancel/Scot Reynolds / Phone: 818-509-0121 / Fax: 818-509-7729 10950 Ventura Blvd, Studio City, CA 91604 / [email protected] . -

FILM (Aggiornato Al 24 Gennaio 2020)

CAD di ARCEVIA ̶ Archivio FILM (aggiornato al 24 Gennaio 2020) Titolo Regista Data Genere Durata Paese N. dvd Trama Una nuova e avvincente avventura ambientata nel tempo in cui i mammuth scuotevano la terra e gli spiriti mistici guidavano il destino dell'uomo. Questo film spettacolare, ricco di effetti speciali e di grande impatto visivo, Avventura, racconta la storia del primo eroe costretto ad affrontare un viaggio pericoloso per liberare la donna che ama e per Drammatico, USA, compiere il suo destino, battendosi contro una tigre dai denti a sciabola e contro altri predatori preistorici, Roland Epico, Nuova attraverserà terre sconosciute, formerà un esercito e scoprirà una civiltà perduta. Lì condurrà la lotta per la 10.000 A.C. Emmerich 2008 Fantastico 110 Zelanda 103 liberazione della sua donna e dinventerà il campione di un'epoca dalla quale la leggenda ha avuto inizio. Matthew incontra la ragazza dei suoi sogni nel buio di un ascensore di un college durante un black out. I due fanno sesso, ma non riescono a vedersi in faccia. Il giorno dopo, il ragazzo, perdutamente innamorato, comincia a cercare la ragazza misteriosa che però sembra sparita nel nulla. Le ragazze che vivono nel college sono ben 100. Ad aiutare Matthew sarà il suo compagno di camera Rod: insieme escogiteranno uno speciale stratagemma per individuare la ragazza "del mistero". Scritto e diretto da Michael Davis, il film, interpretato da attori molto 100 ragazze Micheal Davis 2000 Commedia 90 USA 422 giovani, affronta il tema del sesso presentandoci, talvolta, situazioni imbarazzanti e ai limiti della decenza. THE 100 è fantasioso, sorprendente e divertente. -

Pour Tous Les Goûts Au Monte Carlo Jazz Festival En Page 4 SAINT-JEAN-CAP-FERRAT

Pour tous les goûts au Monte Carlo Jazz Festival en page 4 SAINT-JEAN-CAP-FERRAT Camille Lellouche JEUDI 23 NOVEMBRE 2017 21H - SALLE CHARLIE CHAPLIN Tarif 15€ - Tarif réduit 12€ (-18 ans et étudiants) Placement libre Ouverture des portes 19h30 - Le Charlie’s Bar vous propose une petite restauration sur place RENSEIGNEMENTS +33 (0)4 93 76 08 90 - www.saintjeancapferrat-tourisme.fr sommaire 4 SPECTACLES Monte Carlo Jazz Festival ©Julien Mignot 9 4 6 SPECTACLES 7 ACTU TV Une grande saison aux Muses 8 AGENDA 7 Christophe 9 SPECTACLES 10 ACTU Collet enchante La Chèvre d'Or © BBC 11 ÉVÉNEMENT 7 Eze, village gourmand… 12 RESTO DE LA SEMAINE Ayo La séduisante maison Cottard © Labyrinthe Films / SND CinéFrance Films © Labyrinthe 13 ÉVÉNEMENT l'Affaire SKI Julia Scavo première femme Master of Port Sherlock 14 NEWS GOURMANDES 34 15 RESTO DE LA SEMAINE Une Chaise Bleue très gourmande 33 JEUX 34 AUTOMOBILE Kia Stonic 35 HOROSCOPE 36 LA RECETTE Cavatelli, ris de veau et citron vert Charlot Kia Stonic 36 ACTU 6 18e No Finish Line 3 Télé Monaco І 345 І du 04 novembre au 17 novembre 2017 spectacles ///Pour tous les goûts au Monte Carlo Jazz Festival e Monte-Carlo Jazz Festival va vivre sa 12e édition, du 16 Lnovembre au 2 décembre à l’Opéra Garnier Monte-Carlo avec un programme une nouvelle fois prometteur pour découvrir et redécouvrir les plus grandes stars du jazz, et les talents d’aujourd’hui, dans ce lieu merveilleux, temple de la musique et de la création depuis plus d’un siècle. -

Titlu Titlu Original an Tara R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 S1

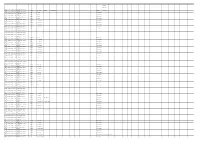

TITLU TITLU ORIGINAL AN TARA R1 R2 R3 R4 R5 R6 R7 R8 R9 R10 S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 S11 S12 S13 S14 S15 S16 Greg Pruss - 13 13 2010 US Gela Babluani Gela Babluani Gregory Pruss Robert Wade - 007: Coordonata Skyfall Skyfall 2012 GB/US Sam Mendes - ALCS Neal Purvis - ALCS ALCS John Logan - ALCS 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.001 episode 1 2008 US Thom Beers Will Raee Philip David Segal Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.002 episode 2 2008 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.003 episode 3 2009 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.004 episode 4 2009 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.005 episode 5 2009 US Will Raee Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.006 episode 6 2009 US Tom McMahon Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.007 episode 7 2009 US Tom McMahon Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.008 episode 8 2009 US Tom McMahon Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.009 episode 9 2009 US Thom Beers Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.010 episode 10 2009 US Thom Beers Tom McMahon 1000 de intamplari mortale - sez.01, 1000 ways to die - season 1, ep.011 episode -

Programme Télé Cinéma

La phrase de la semaine Je ne suis plus fâché avec Manu Katché ! Demain PROGRAMME André Manoukian en TÉLÉ CINÉMA Nouvelle-Calédonie Semaine du samedi 17 février au vendredi 24 février 2012 BIG MAMMA 2 20h30 MILLENIUM : LES HOMMES QUI Du vendredi 17 février au N’AIMAIENT PAS LES FEMMES 13h50, vendredi 24 février 2012 BOURAIL AU CINÉMA 20h00 FOOTLOOSE 17h15 ZARAFA VENDREDI 17 FÉVRIER À 18H30 14h25, 18h15 SHERLOCK HOLMES : LES MARCHES DU POUVOIR CINÉCITY JEU D’OMBRES 13h30, 17h25, 20h10 J. LA FOA SAMEDI 18 FÉVRIER À 18H30 Du mercredi 22 au mardi 28 février 2012 EDGAR 20h05 HOLLYWOO 13h50, 18h15, SAMEDI 18 FEVRIER A 17H30 LES AVENTURES DE TINTIN 20h40 ALVIN & LES CHIPMUNKS 3 13h55, HAPPY FEET 2 MERCREDI 22 FÉVRIER À 14H VOYAGE AU CENTRE DE LA TERRE 15h55, 18h00 INTOUCHABLES 14h15, SAMEDI 18 FEVRIER A 19H30 HAPPY NEW YEAR JEUDI 23 ET VENDREDI 2 : L’ILE MYSTERIEUSE 13h40, 16h00, 18h10, 20h35 MISSION IMPOSSIBLE : TWILIGHT 4.1 24 FÉVRIER À 18H30 18h25, 20h55 14h05, 17h40, MERCREDI 22 FEVRIER A 17H30 LA TAUPE PROTOCOLE FANTOME 14h25, 17h15, LES IMMORTELS 20h25 LA DELICATESSE 14h20, 17h55, 20h00 LE CHAT POTTE 2D 2D : 16h10 TINTIN (enfant à partir de 6 ans) 20h50 STAR WARS EP. 1 : LA MENACE JEUDI 23 FEVRIER A 18H30 LES FANTOME 14h00, 17h35, 20h20 FELINS MARCHES DU POUVOIR 16h15, 20h40 THE LADY 14h10, 17h45, PLATEAU TÉLÉ SALÉ/SUCRÉ AU MENU DE VOS ENVIES Ô soleil ! Cuisine ensoleillée... Taboulé du soleil Sorbet léger à la noix de coco Pour 4 personnes 1 Rincez le boulgour et faites-le tremper Préparation 40 mn pendant 20 min, dans l’eau tiède citronnée. -

In This Issue

APRIL 2012 In this Issue: t 1SPEVDUJPO*ODFOUJWFT6QEBUF t "5SJCVUFUP%JSFDUPS1BSJT#BSDMBZ t 'JSTU"%$SBGU4FNJOBSChanging Landscapes t "QSJM4DSFFOJOHT .FFUJOHTBOE&WFOUT APRIL MONTHLY VOLUME 9, NUMBER 4 Contents 1 9 APRIL APRIL MEETINGS CALENDAR: LOS ANGELES & PayReel provides payroll and contractor SAN FRANCISCO 2-3 management services for video and DGA NEWS media, broadcast and film customers. 10-13 MEMBERSHIP Our clients depend on us to take the hassle 4-7 SCREENINGS UPCOMING out of hiring, managing and paying free- EVENTS lance contractors while reducing the risk of 15-19 RECENT employee misclassification and compliance 8 EVENTS complications. APRIL CALENDAR: NEW YORK, 20 Freelance Contractor Services CHICAGO, MEMBERSHIP Visit payreel.com Or call 800.352.7397 & WASHINGTON REPORT Need A Crew? Visit our crewing resource at www.crewconnection.com DGA COMMUNICATIONS DEPARTMENT Morgan Rumpf Assistant Executive Director, Communications Sahar Moridani Director of Media Relations Darrell L. Hope Editor, DGA Monthly & dga.org James Greenberg Editor, DGA Quarterly Tricia Noble Graphic Designer Jackie Lam Publications Associate Carley Johnson Communications Associate Caitlin Jarrett Communications Associate CONTACT INFORMATION 7920 Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90046-0907 www.dga.org (310) 289-2082 F: (310) 289-5384 E-mail: [email protected] PRINT PRODUCTION & ADVERTISING IngleDodd Publishing Dan Dodd - Advertising Director (310) 207-4410 ex. 236 E-mail: [email protected] DGA MONTHLY (USPS 24052) is published monthly by the Directors Guild of America, Inc., 7920 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90046-0907. Periodicals Postage paid at Los Angeles, CA 90052. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $6.00 of each Directors Guild of America member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to DGA MONTHLY.