Fleming Umn 0130E 10470.Pdf (7.855Mb Application/Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View / Open Gregory Oregon 0171N 12796.Pdf

CHUNKEY, CAHOKIA, AND INDIGENOUS CONFLICT RESOLUTION by ANNE GREGORY A THESIS Presented to the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science June 2020 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Anne Gregory Title: Chunkey, Cahokia, and Indigenous Conflict Resolution This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Conflict and Dispute Resolution Program by: Kirby Brown Chair Eric Girvan Member and Kate Mondloch Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2020. ii © 2020 Anne Gregory This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Anne Gregory Master of Science Conflict and Dispute Resolution June 2020 Title: Chunkey, Cahokia, and Indigenous Conflicts Resolution Chunkey, a traditional Native American sport, was a form of conflict resolution. The popular game was one of several played for millennia throughout Native North America. Indigenous communities played ball games not only for the important culture- making of sport and recreation, but also as an act of peace-building. The densely populated urban center of Cahokia, as well as its agricultural suburbs and distant trade partners, were dedicated to chunkey. Chunkey is associated with the milieu surrounding the Pax Cahokiana (1050 AD-1200 AD), an era of reduced armed conflict during the height of Mississippian civilization (1000-1500 AD). The relational framework utilized in archaeology, combined with dynamics of conflict resolution, provides a basis to explain chunkey’s cultural impact. -

Megaliths and the Early Mezcala Urban Tradition of Mexico

ICDIGITAL Separata 44-45/5 ALMOGAREN 44-45/2013-2014MM131 ICDIGITAL Eine PDF-Serie des Institutum Canarium herausgegeben von Hans-Joachim Ulbrich Technische Hinweise für den Leser: Die vorliegende Datei ist die digitale Version eines im Jahrbuch "Almogaren" ge- druckten Aufsatzes. Aus technischen Gründen konnte – nur bei Aufsätzen vor 1990 – der originale Zeilenfall nicht beibehalten werden. Das bedeutet, dass Zeilen- nummern hier nicht unbedingt jenen im Original entsprechen. Nach wie vor un- verändert ist jedoch der Text pro Seite, so dass Zitate von Textstellen in der ge- druckten wie in der digitalen Version identisch sind, d.h. gleiche Seitenzahlen (Pa- ginierung) aufweisen. Der im Aufsatzkopf erwähnte Erscheinungsort kann vom Sitz der Gesellschaft abweichen, wenn die Publikation nicht im Selbstverlag er- schienen ist (z.B. Vereinssitz = Hallein, Verlagsort = Graz wie bei Almogaren III). Die deutsche Rechtschreibung wurde – mit Ausnahme von Literaturzitaten – den aktuellen Regeln angepasst. Englischsprachige Keywords wurden zum Teil nach- träglich ergänzt. PDF-Dokumente des IC lassen sich mit dem kostenlosen Adobe Acrobat Reader (Version 7.0 oder höher) lesen. Für den Inhalt der Aufsätze sind allein die Autoren verantwortlich. Dunkelrot gefärbter Text kennzeichnet spätere Einfügungen der Redaktion. Alle Vervielfältigungs- und Medien-Rechte dieses Beitrags liegen beim Institutum Canarium Hauslabgasse 31/6 A-1050 Wien IC-Separatas werden für den privaten bzw. wissenschaftlichen Bereich kostenlos zur Verfügung gestellt. Digitale oder gedruckte Kopien von diesen PDFs herzu- stellen und gegen Gebühr zu verbreiten, ist jedoch strengstens untersagt und be- deutet eine schwerwiegende Verletzung der Urheberrechte. Weitere Informationen und Kontaktmöglichkeiten: institutum-canarium.org almogaren.org Abbildung Titelseite: Original-Umschlag des gedruckten Jahrbuches. -

Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains Edited by George C

Tri-Services Cultural Resources Research Center USACERL Special Report 97/2 December 1996 U.S. Department of Defense Legacy Resource Management Program U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Construction Engineering Research Laboratory Archeological and Bioarcheological Resources of the Northern Plains edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort, with contributions by George C. Frison, Dennis L. Toom, Michael L. Gregg, John Williams, Laura L. Scheiber, George W. Gill, James C. Miller, Julie E. Francis, Robert C. Mainfort, David Schwab, L. Adrien Hannus, Peter Winham, David Walter, David Meyer, Paul R. Picha, and David G. Stanley A Volume in the Central and Northern Plains Archeological Overview Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 47 1996 Arkansas Archeological Survey Fayetteville, Arkansas 1996 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Archeological and bioarcheological resources of the Northern Plains/ edited by George C. Frison and Robert C. Mainfort; with contributions by George C. Frison [et al.] p. cm. — (Arkansas Archeological Survey research series; no. 47 (USACERL special report; 97/2) “A volume in the Central and Northern Plains archeological overview.” Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-56349-078-1 (alk. paper) 1. Indians of North America—Great Plains—Antiquities. 2. Indians of North America—Anthropometry—Great Plains. 3. Great Plains—Antiquities. I. Frison, George C. II. Mainfort, Robert C. III. Arkansas Archeological Survey. IV. Series. V. Series: USA-CERL special report: N-97/2. E78.G73A74 1996 96-44361 978’.01—dc21 CIP Abstract The 12,000 years of human occupation in the Northwestern Great Plains states of Montana, Wyoming, North Dakota, and South Dakota is reviewed here. -

1992 Program + Abstracts

The J'J'l!. Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference 1 1 ' ll\T ii~,, !,II !ffll}II II I ~\: ._~ •,.i.~.. \\\•~\,'V · ''f••r·.ot!J>,. 1'1.~•~'l'rl!nfil . ~rt~~ J1;1r:1ri WA i1. '1~;111.-U!!•ac~~ 1.!\ ill: 11111m I! nIn 11n11 !IIIIIIII Jill!! lTiili 11 HJIIJJll llIITl nmmmlllll Illlilll 1IT1Hllll .... --·---------- PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS October 16-18, 1992 Grand Rapids, Michigan F Con£eren ·, MAC 1992 Midwest Archaeological Conference 37!!! Annual Meeting October 16-18, 1992 Grand Rapids, Michigan Sponsored By: The Grand Valley State University Department of Anthropology and Sociology The Public Museum of Grand Rapids CONFERENCE ORGANIZING C0MMITIEE Janet BrashlerElizabeth ComellFred Vedders Mark TuckerPam BillerJaret Beane Brian KwapilJack Koopmans The Department of Anthropology and Sociology gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following organizations for their assistance in planning the 1992 Midwest Archaeological Conference: The Grand Valley State University Conference Planning Office The Office of the President, Grand Valley State University The Anthropology Student Organization The Public Museum of Grand Rapids Cover Rlustration: Design from Norton Zoned Dentate Pot, Mound C, Norton Mounds 8f(!r/!lA_. ARCHIVES ;z.g-'F' Office of the State Archaeologist The Universi~i of Iowa ~ TlA<-, Geuetftf 1'l!M&rmation \"l,_ "2. Registration Registration is located on the second floor of the L.V. Eberhard Center at the Conference Services office. It will be staffed from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 16; 7:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 17; and from 7:30 a.m. -

Rock Art Studies: a Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17

Rock Art Studies: A Bibliographic Database Page 1 800 Citations: Compiled by Leigh Marymor 04/12/17 Keywords: Peterborough, Canada. North America. Cultural Adams, Amanda Shea resource management. Conservation and preservation. 2003 Reprinted from "Measurement in Physical Geography", Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Occasional Paper No. 3, Dept. of Geography, Trent Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, BCMaster/s Thesis :79 pgs, University, 1974. Weathering. University of British Columbia. Cited from: LMRAA, WELLM, BCSRA. Keywords: Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada. North America. Stylistic analysis. Marpole Culture. Vision. Alberta Recreation and Parks Abstract: "This study explores the stylistic variability and n.d. underlying cohesion of the petroglyphs sites located on Writing-On-Stone Provincial ParkTourist Brochure, Alberta Gabriola Island, British Columbia, a southern Gulf Island in Recreation and Parks. the Gulf of Georgia region of the Northwest Coast (North America). I view the petroglyphs as an inter-related body of Keywords: WRITING-ON-STONE PROVINCIAL PARK, ancient imagery and deliberately move away from (historical ALBERTA, CANADA. North America. "THE BATTLE and widespread) attempts at large regional syntheses of 'rock SCENE" PETROGLYPH SITE INSERT INCLUDED WITH art' and towards a study of smaller and more precise PAMPHLET. proportion. In this thesis, I propose that the majority of petroglyphs located on Gabriola Island were made in a short Cited from: RCSL. period of time, perhaps over the course of a single life (if a single, prolific specialist were responsible for most of the Allen, W.A. imagery) or, at most, over the course of a few generations 2007 (maybe a family of trained carvers). -

Cultural Affiliation Statement for Buffalo National River

CULTURAL AFFILIATION STATEMENT BUFFALO NATIONAL RIVER, ARKANSAS Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño Nicholas Laluk Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Contract Agreement CA 1248-00-02 Task Agreement J6068050087 UAZ-176 Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85711 June 1, 2008 Table of Contents and Figures Summary of Findings...........................................................................................................2 Chapter One: Study Overview.............................................................................................5 Chapter Two: Cultural History of Buffalo National River ................................................15 Chapter Three: Protohistoric Ethnic Groups......................................................................41 Chapter Four: The Aboriginal Group ................................................................................64 Chapter Five: Emigrant Tribes...........................................................................................93 References Cited ..............................................................................................................109 Selected Annotations .......................................................................................................137 Figure 1. Buffalo National River, Arkansas ........................................................................6 Figure 2. Sixteenth Century Polities and Ethnic Groups (after Sabo 2001) ......................47 -

Households and Changing Use of Space at the Transitional Early Mississippian Austin Site

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 Households and Changing Use of Space at the Transitional Early Mississippian Austin Site Benjamin Garrett Davis University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Benjamin Garrett, "Households and Changing Use of Space at the Transitional Early Mississippian Austin Site" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1570. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1570 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOUSEHOLDS AND CHANGING USE OF SPACE AT THE TRANSITIONAL EARLY MISSISSIPPIAN AUSTIN SITE A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology University of Mississippi by BENJAMIN GARRETT DAVIS May 2019 ABSTRACT The Austin Site (22TU549) is a village site located in Tunica County, Mississippi dating to approximately A.D. 1150-1350, along the transition from the Terminal Late Woodland to the Mississippian period. While Elizabeth Hunt’s (2017) masters thesis concluded that the ceramics at Austin emphasized a Late Woodland persistence, the architecture and use of space at the site had yet to be analyzed. This study examines this architecture and use of space over time at Austin to determine if they display evidence of increasing institutionalized inequality. This included creating a map of Austin based on John Connaway’s original excavation notes, and then analyzing this map within the temporal context of the upper Yazoo Basin. -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

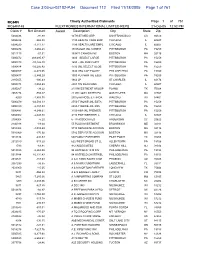

Case 3:03-Cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761

Case 3:03-cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761 MC64N Timely Authorized Claimants Page 1 of 761 MC64N148 FLEXTRONICS INTERNATIONAL LIMITED REPS 21-Oct-05 12:52 PM Claim #Net Amount Award Description City State Zip 5002436 -91.88 10TH ST MED GRP SAN FRANCISCO CA 94120 5004224 -965.80 1199 HEALTH CARE EMP CHICAGO IL 60607 5004220 -3,717.17 1199 HEALTHCARE EMPL CHICAGO IL 60607 5000476 -3,602.28 150 EAGLE JNL CORE E PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5011113 -57.51 159471 CANADA INC BOSTON MA 02116 5000472 -269,695.87 1600 - SELECT LARGE PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000473 -10,126.40 1650 - JNL FMR CAPIT PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000474 -93,205.42 1700 JNL SELECT GLOB PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5009707 -6,478.05 1838 LRG CAP EQUITY PHILADELPHIA PA 19109 5000477 -2,849.29 1900 PUTNAM JNL EQUI PITTSBURGH PA 15259 2185655 -100.43 1966 LP ST CHARLES IL 60174 5003474 -1,053.69 2001 TIN MAN FUND CHICAGO IL 60607 2095267 -38.22 210 INVESTMENT GROUP PLANO TX 75024 2057274 -755.37 22 WILLOW LIMITED PA OAK BLUFFS MA 02557 4259 -1,853.75 230 EAR NOSE & THROA WAUSAU WI 54401 5000479 -44,584.33 2750-T ROWE-JNL ESTA PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000480 -2,457.83 2850-T ROWE-JNL MID- PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000481 -4,348.61 3150-AIM-JNL PREMIER PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5004002 -2,648.80 3180 PARTNERSHIP, L. CHICAGO IL 60607 2104008 -5.20 5 - W ASSOCIATES ANDERSON SC 29622 2146318 -83.04 55 PLUS INVESTMENT BRUNSWICK ME 04011 5010968 -4,083.69 5710 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 5010969 -170.92 5782 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 1013184 -230.59 5D FAMILY PARTNERS PILET POINT TX 76258 -

An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2004 An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas William Glenn Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hill, William Glenn, "An Intensive Surface Collection and Intrasite Spatial Analysis of the Archaeological Materials from the Coy Mound Site (3LN20), Central Arkansas" (2004). Master's Theses. 3873. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3873 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN INTENSIVE SURFACE COLLECTION AND INTRASITE SPATIAL ANALYSIS OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL MATERIALS FROM THE COY MOUND SITE (3LN20), CENTRAL ARKANSAS by William Glenn Hill A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts Department of Anthropology WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2004 Copyright by William Glenn Hill 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Foremost, my pursuit in archaeology would be less meaningful without the accomplishments of Dr. Randall McGuire, Dr. H. Martin Wobst, and Dr. Michael Nassaney. They have provided a theoretical perspective in archaeology that has integrated and given greater meaning to my own social and archaeological interests. I would especially like to especially thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Michael Nassaney, for the stimulating opportunity to explore research within this theoretical perspective, and my other committee members, Dr. -

Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1939 Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Seale, Lea Leslie, "Indian Place-Names in Mississippi." (1939). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7812. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7812 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the master^ and doctorfs degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Library are available for inspection* Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author* Bibliographical references may be noted3 but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission# Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work# A library which borrows this thesis for vise by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions, LOUISIANA. STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 119-a INDIAN PLACE-NAMES IN MISSISSIPPI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisian© State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Lea L # Seale M* A*, Louisiana State University* 1933 1 9 3 9 UMi Number: DP69190 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE WISTER AREA FOURCHE MALINE: A CONTESTED LANDSCAPE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By SIMONE BACHMAI ROWE Norman, OKlahoma 2014 WISTER AREA FOURCHE MALINE: A CONTESTED LANDSCAPE A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. Lesley RanKin-Hill, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Don Wyckoff, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Diane Warren ______________________________ Dr. Patrick Livingood ______________________________ Dr. Barbara SafiejKo-Mroczka © Copyright by SIMONE BACHMAI ROWE 2014 All Rights Reserved. This work is dedicated to those who came before, including my mother Nguyen Thi Lac, and my Granny (Mildred Rowe Cotter) and Bob (Robert Cotter). Acknowledgements I have loved being a graduate student. It’s not an exaggeration to say that these have been the happiest years of my life, and I am incredibly grateful to everyone who has been with me on this journey. Most importantly, I would like to thank the Caddo Nation and the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes for allowing me to work with the burials from the Akers site. A great big thank you to my committee members, Drs. Lesley Rankin-Hill, Don Wyckoff, Barbara Safjieko-Mrozcka, Patrick Livingood, and Diane Warren, who have all been incredibly supportive, helpful, and kind. Thank you also to the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, where most of this work was carried out. I am grateful to many of the professionals there, including Curator of Archaeology Dr. Marc Levine and Collections Manager Susie Armstrong-Fishman, as well as Curator Emeritus Don Wyckoff, and former Collection Managers Liz Leith and Dr.