Chaillot Paper 89

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan-Iran Relations Japan-Iran Relations June 2009

1. Japan-Iran Relations Japan-Iran Relations June 2009 (1) Japan-Iran Political Relations • Japan highly values its relations with the Islamic Republic of Iran in view of a stable supply of crude oil and ensure stability in the Middle East. • Based on friendly relations, Japan has conveyed Iran of its stance, as well as the international community’s stern view, on the nuclear issue. • Last year, Japan continued to maintain a close exchange of views with Iran through mutual visits, including the Regular Japan-Iran Vice-Ministerial Consultations in May in Teheran and in December in Tokyo; a visit to Japan in February by Dr. Mohammad-Javad ARDASHIR=LARIJANI, Secretary General of National Supreme Council of Human Rights of the Judiciary; a visit to Iran in June by Senior Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs Itsunori Onodera; a visit to Japan in October by H.E. Dr. Mohammad Baqer Ghalibaf, Mayor of Tehran; a visit to Iran in November by Mr. Taro Nakayama, chairman of the Japan-Iran Parliamentarians Friendship League; and a visit to Japan in November by Vice President Esfandyar Rahim MASHAEE. This year, Minister for Foreign Affairs Hirofumi Nakasone held a telephone conference in January with Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs Manouchehr Mottaki (on the situation in Gaza). Mr. Samareh Hashemi, Senior Advisor to the President of Iran, visited Japan as a special presidential envoy, and met with Prime Minister Taro Aso, Chief Cabinet Secretary Takeo Kawamura, and Foreign Minister Nakasone. In April, Foreign Minister Mottaki visited Japan to attend the Pakistan Donors Conference and met with Prime Minister Aso and Foreign Minister Nakasone. -

Blood-Soaked Secrets Why Iran’S 1988 Prison Massacres Are Ongoing Crimes Against Humanity

BLOOD-SOAKED SECRETS WHY IRAN’S 1988 PRISON MASSACRES ARE ONGOING CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover photo: Collage of some of the victims of the mass prisoner killings of 1988 in Iran. Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons © Amnesty International (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 13/9421/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 METHODOLOGY 18 2.1 FRAMEWORK AND SCOPE 18 2.2 RESEARCH METHODS 18 2.2.1 TESTIMONIES 20 2.2.2 DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE 22 2.2.3 AUDIOVISUAL EVIDENCE 23 2.2.4 COMMUNICATION WITH IRANIAN AUTHORITIES 24 2.3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 25 BACKGROUND 26 3.1 PRE-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 26 3.2 POST-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 27 3.3 IRAN-IRAQ WAR 33 3.4 POLITICAL OPPOSITION GROUPS 33 3.4.1 PEOPLE’S MOJAHEDIN ORGANIZATION OF IRAN 33 3.4.2 FADAIYAN 34 3.4.3 TUDEH PARTY 35 3.4.4 KURDISH DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF IRAN 35 3.4.5 KOMALA 35 3.4.6 OTHER GROUPS 36 4. -

(English-Kreyol Dictionary). Educa Vision Inc., 7130

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 401 713 FL 023 664 AUTHOR Vilsaint, Fequiere TITLE Diksyone Angle Kreyol (English-Kreyol Dictionary). PUB DATE 91 NOTE 294p. AVAILABLE FROM Educa Vision Inc., 7130 Cove Place, Temple Terrace, FL 33617. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Vocabularies /Classifications /Dictionaries (134) LANGUAGE English; Haitian Creole EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alphabets; Comparative Analysis; English; *Haitian Creole; *Phoneme Grapheme Correspondence; *Pronunciation; Uncommonly Taught Languages; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *Bilingual Dictionaries ABSTRACT The English-to-Haitian Creole (HC) dictionary defines about 10,000 English words in common usage, and was intended to help improve communication between HC native speakers and the English-speaking community. An introduction, in both English and HC, details the origins and sources for the dictionary. Two additional preliminary sections provide information on HC phonetics and the alphabet and notes on pronunciation. The dictionary entries are arranged alphabetically. (MSE) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** DIKSIONt 7f-ngigxrzyd Vilsaint tick VISION U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement EDU ATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS CENTER (ERIC) MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization originating it. \hkavt Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. BEST COPY AVAILABLE Points of view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES official OERI position or policy. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." 2 DIKSYCAlik 74)25fg _wczyd Vilsaint EDW. 'VDRON Diksyone Angle-Kreyal F. Vilsaint 1992 2 Copyright e 1991 by Fequiere Vilsaint All rights reserved. -

Iran's Nuclear Ambitions From

IDENTITY AND LEGITIMACY: IRAN’S NUCLEAR AMBITIONS FROM NON- TRADITIONAL PERSPECTIVES Pupak Mohebali Doctor of Philosophy University of York Politics June 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the impact of Iranian elites’ conceptions of national identity on decisions affecting Iran's nuclear programme and the P5+1 nuclear negotiations. “Why has the development of an indigenous nuclear fuel cycle been portrayed as a unifying symbol of national identity in Iran, especially since 2002 following the revelation of clandestine nuclear activities”? This is the key research question that explores the Iranian political elites’ perspectives on nuclear policy actions. My main empirical data is elite interviews. Another valuable source of empirical data is a discourse analysis of Iranian leaders’ statements on various aspects of the nuclear programme. The major focus of the thesis is how the discourses of Iranian national identity have been influential in nuclear decision-making among the national elites. In this thesis, I examine Iranian national identity components, including Persian nationalism, Shia Islamic identity, Islamic Revolutionary ideology, and modernity and technological advancement. Traditional rationalist IR approaches, such as realism fail to explain how effective national identity is in the context of foreign policy decision-making. I thus discuss the connection between national identity, prestige and bargaining leverage using a social constructivist approach. According to constructivism, states’ cultures and identities are not established realities, but the outcomes of historical and social processes. The Iranian nuclear programme has a symbolic nature that mingles with socially constructed values. There is the need to look at Iran’s nuclear intentions not necessarily through the lens of a nuclear weapons programme, but rather through the regime’s overall nuclear aspirations. -

Download Report

Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy Report April 2014 smallmedia.org.uk This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License INTRODUCTION // Despite the election of the moderate Hassan Rouhani to the presidency last year, Iran’s systematic filtering of online content and mobile phone apps continues at full-pace. In this month’s edition of the Iranian Internet Infrastructure and Policy Report, Small Media takes a closer look at one of the bodies most deeply-enmeshed with the process of overseeing and directing filtering policies - the ‘Commission to Determine the Instances of Criminal Content’ (or CDICC). This month’s report also tracks all the usual news about Iran’s filtering system, national Internet policy, and infrastructure development projects. As well as tracking high-profile splits in the estab- lishment over the filtering of the chat app WhatsApp, this month’s report also finds evidence that the government has begun to deploy the National Information Network (SHOMA), or ‘National Internet’, with millions of Iranians using it to access the government’s new online platform for managing social welfare and support. 2 THE COMMISSION TO DETERMINE THE INSTANCES OF CRIMINAL CONTENT (CDICC) THE COMMISSION TO DETERMINE THE INSTANCES OF CRIMINAL CONTENT (CDICC) overview The Commission to Determine the Instances of Criminal Content (CDICC) is the body tasked with monitoring cyberspace, and filtering criminal Internet content. It was established as a consequence of Iran’s Cyber Crime Law (CCL), which was passed by Iran’s Parliament in May 2009. According to Article 22 of the CCL, Iran’s Judiciary System was given the mandate of establishing CDICC under the authority of Iran’s Prosecutor’s Office. -

Supreme Leader Appoints Members for the New Term of the Expediency Council - 14 /Mar/ 2012

Supreme Leader Appoints Members for the New Term of the Expediency Council - 14 /Mar/ 2012 In the Name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful I am thankful to Allah the Exalted that with Allah’s grace, the Expediency Council managed to finish another 5-year term with an acceptable record and hopefully the outcomes and benefits of the legal measures of the council will produce good results in managerial areas of the country – the three branches of government, the Armed Forces and other organizations – and everybody will see the outcomes. I would like to thank all of the esteemed members, the chairman and the secretariat of the council and for the new 5-year term, I hereby assign the following legal and natural persons under the chairmanship of Hojjatoleslam wal- Muslemin Hashemi Rafsanjani: The legal persons are as follows: Heads of the three branches of government Jurisprudents of the Guardian Council The secretary of the Supreme National Security Council The minister or chairperson of the relevant organization The chairperson of the relevant parliamentary commissions The natural persons are as follows: Mr. Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mr. Hajj Sheikh Ahmad Jannati, Mr. Vaez Tabasi, Mr. Amini Najafabadi, Mr. Seyyed Mahmoud Hashemi Shahroudi, Mr. Movahedi Kermani, Mr. Ali-Akbar Nategh-Nuri, Mr. Hajj Sheikh Hasan Sanei, Mr. Hasan Rouhani, Mr. Dorri Najafabadi, Mr. Gholam-Hossein Mohseni, Mr. Mahmoud Mohammadi Eraghi, Mr. Gholam-Reza Mesbahi Moghaddam, Mr. Majid Ansari, Mr. Gholam-Reza Aghazadeh, Mr. Ali Agha-Mohammadi, Mr. Mohammad-Javad Iravani, Mr. Mohammad-Reza Bahonar, Mr. Gholam-Ali Haddad Adel, Mr. Hasan Habibi, Page 1 / 2 Mr. -

USAF Counterproliferation Center CPC Outreach Journal #867

USAF COUNTERPROLIFERATION CENTER CPC OUTREACH JOURNAL Maxwell AFB, Alabama Issue No. 867, 14 December 2010 Articles & Other Documents: WH: Obama Won't Leave DC until Nuke Deal is Done S. Korea, U.S. Launch Joint Committee to Deter N. Korea's Nuclear Threats START Pact Has Enough Votes, U.S. Aide Says N Korea's Nuclear Capacity Worries Russia Clock Ticking, Obama Urges Senate OK of Arms Treaty S.Korea Suspects Secret Uranium Enrichment in North Senate Working on Ratification of U.S.-Russian Strategic Arms Treaty - White House US Suspects Secret Burma Nuclear Sites Manouchehr Mottaki Fired from Iran Foreign Minister Burma Not Nuclear, Says Abhisit Job Test of Agni-II's Advanced Version Fails Intelligence Chiefs Fear Nuclear War between Israel and Tehran Russian Military to Receive 1,300 Types of Weaponry by 2020 Rudd Calls for Inspections of Israel's Nuclear Facility Russia, NATO May Make Soon Progress in Joint Iran Foreign Policy 'Unchanged' by Mottaki Sacking Missile Defense Progress North Korea Stresses Commitment to Nuclear Weapons Bolivia Rejects Alvaro Uribe’s Accusations about Nuclear Program N. Korean FM Defends Pyongyang's Decision to Bolster Nuclear Arsenal U.S. to Spend $1B Over Five Years on Conventional Strike Systems Japan Plans more Patriot Systems to Shoot Down N. Korean Missiles Talks with Iran Just a Start Iran's Nuclear Plans Give West a Tough Choice Welcome to the CPC Outreach Journal. As part of USAF Counterproliferation Center’s mission to counter weapons of mass destruction through education and research, we’re providing our government and civilian community a source for timely counterproliferation information. -

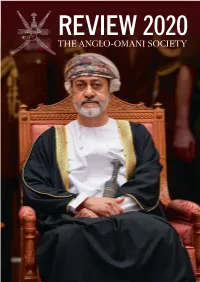

THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ Business Is to Build, Manage and Protect Our Clients’ Reputations

REVIEW 2020 THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY THE ANGLO-OMANI SOCIETY REVIEW 2020 Project Associates’ business is to build, manage and protect our clients’ reputations. Founded over 20 years ago, we advise corporations, individuals and governments on complex communication issues - issues which are usually at the nexus of the political, business, and media worlds. Our reach, and our experience, is global. We often work on complex issues where traditional models have failed. Whether advising corporates, individuals, or governments, our goal is to achieve maximum targeted impact for our clients. In the midst of a media or political crisis, or when seeking to build a profile to better dominate a new market or subject-area, our role is to devise communication strategies that meet these goals. We leverage our experience in politics, diplomacy and media to provide our clients with insightful counsel, delivering effective results. We are purposefully discerning about the projects we work on, and only pursue those where we can have a real impact. Through our global footprint, with offices in Europe’s major capitals, and in the United States, we are here to help you target the opinions which need to be better informed, and design strategies so as to bring about powerful change. Corporate Practice Private Client Practice Government & Political Project Associates’ Corporate Practice Project Associates’ Private Client Project Associates’ Government helps companies build and enhance Practice provides profile building & Political Practice provides strategic their reputations, in order to ensure and issues and crisis management advisory and public diplomacy their continued licence to operate. for individuals and families. -

2009 SEM Honorary Member: Lois Ann Anderson Weapons of Mass In

Volume 44 Number 1 January 2010 curriculum. She directed the Ugandan 2009 SEM Honorary kiganda xylophone study group from Inside Member: Lois Ann 1975-2008 and she directed/coordi- 1 2009 SEM Honorary Member nated the Javanese gamelan ensem- 1 Weapons of Mass Instruction Anderson ble from 1976-1982. 3 People and Places Lois’s colleagues in musicology By Portia K. Maultsby, Virginia Gor- 4 nC embraced her vision for a broader 2 linski, and Mellonee Burnim 7 54th Annual Meeting curriculum and a more comprehen- 9 Prizes Lois Ann Anderson was among sive approach to the study of music 11 President’s Report the first generation of ethnomusicolo- traditions, integrating ethnomusicol- 13 Calls for Participation gists to graduate from UCLA and to ogy courses into the musicology 15 SEM Crossroads Project establish ethnomusicology programs program and including related content 15 Resolution of Thanks at major research institutions through- on PhD exams. The School of Music 17 Announcements out the country. After receiving her also adopted a more democratic 21 Conferences Calendar PhD under the directorship of Mantle administrative structure that rotated division chairs between the two disciplines. Over Weapons of Mass In- her forty years at the University of struction Wisconsin, Lois By Gage Averill, SEM President served as chair several times and “Ethnomusicology At the End Of she served as Di- Petroglobalization” rector of the Cen- You will notice as you attempt to ter for Southeast open up this edition of the Asian Studies Newslet- and spread it on the desk that it from 1981-1982. ter is no longer made of paper. -

Iran, Country Information

Iran, Country Information COUNTRY ASSESSMENT - IRAN April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III HISTORY IV STATE STRUCTURES VA HUMAN RIGHTS - OVERVIEW VB HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VC HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A - CHRONOLOGY ANNEX B - POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS ANNEX C - PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D - REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1. This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2. The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum/human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum/human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3. The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4. It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY 2.1. The Islamic Republic of Iran Persia until 1935 lies in western Asia, and is bounded on the north by the file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Iran.htm[10/21/2014 9:57:59 AM] Iran, Country Information Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, by Turkey and Iraq to the west, by the Persian Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman to the south, and by Pakistan and Afghanistan to the east. -

Будућност Историје Музике the Future of Music History

Будућност историје музике The Future II/2019 of Music History 27 Реч уреднице Editor's Note ема броја 27 Будућност историје музике инспирисана је истоименим Тсеминаром, организованим у оквиру конференције одржане у Српској History академији наука и уметности септембра 2017. године. Организатор семинара био је Џим Самсон, један од најзначајнијих музиколога данашњице, емеритус професор колеџа Ројал Холовеј Универзитета у Лондону, редовни члан Британске Академије и аутор више од 100 Будућност публикација, међу којима је и прва обухватна историја музике на Балкану на енглеском језику (Music in the Balkans, Leiden: Brill, 2013). Проф. The Future Самсон је љубазно прихватио наш позив да буде гост-уредник овог броја часописа, у којем објављујемо радове четворо од петоро учесника панела историје Будућност историје музике (Рајнхарда Штрома, Мартина Лесера, Кетрин Елис и Марине Фролове-Вокер). Изражавамо велику захвалност овим еминентним музиколозима на исцрпном промишљању будућности музике музике наше дисциплине и настојањима да предмет изучавања постану географске регије, друштвени слојеви и слушалачке праксе који су досад били занемарени у музиколошким разматрањима. he theme of the issue No 27 The Future of Music History was inspired by the Teponymous seminar organised as part of a conference held at the Serbian The Future Academy of Sciences and Arts in September 2017. The seminar was prepared by Jim Samson, one of the most outstanding musicologists of our time, Emeritus Professor of Music, Royal Holloway (University of London), member of Music of the British Academy and author of more than 100 publications, including the first comprehensive history of music in the Balkans in English (Leiden: Brill, Будућност историје 2013). Professor Samson kindly accepted our invitation to be the guest editor History of this issue, in which we publish articles by four of the five panelists (Reinhard Strohm, Martin Loeser, Katharine Ellis and Marina Frolova-Walker). -

Ahmadinezhad's Cabinet: Loyalists and Radicals

PolicyWatch #1571 Ahmadinezhad's Cabinet: Loyalists and Radicals By Mehdi Khalaji August 21, 2009 On August 19, Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinezhad submitted his list of cabinet nominees to the Majlis (Iran's parliament). The president's choice of individuals clearly shows his preference for loyalty over efficiency, as he fired every minister who, while strongly supportive of him on most issues, opposed him recently on his controversial decision to appoint a family relative as first vice president. Ahmadinezhad's drive to install loyalists involves placing members of the military and intelligence community in the cabinet, as well as in other important government positions. Despite the president's positioning, Iran's top leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, remains in firm control of the country's vital ministries. Cabinet Approval On August 23, the Majlis will either approve or challenge the president's cabinet appointments. Ahmadinezhad has a relatively free hand to choose the majority of cabinet seats, but the country's key ministries -- intelligence, interior, foreign affairs, defense, and culture and Islamic guidance -- are, in all practical terms, preapproved by Khamenei before the president submits their names. As such, the Majlis is all but guaranteed to accept these particular individuals. The president is also empowered to directly appoint the secretary of the Supreme Council for National Security (SCNS) -- the individual responsible for Iran's nuclear dossier and negotiations -- but because this position is of particular importance to Khamanei, it also must be preapproved. Economic and Foreign Affairs Ahmadinezhad's nominations suggest that he is not bothered by the ongoing criticism of his foreign policy and economic agenda, since the ministers of foreign affairs, industries and mines, economic affairs, cooperatives, and roads and transport will remain unchanged.