Factors Affecting the Decline of Bus Use In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

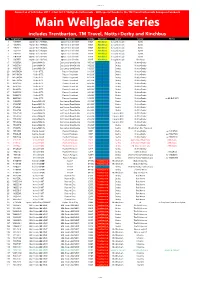

Wellglade Series Includes Trentbarton, TM Travel, Notts+Derby and Kinchbus No

Main series Correct as of 6 October 2017 • Fleet list © Wellglade Enthusiasts • With special thanks to the TM Travel Enthusiasts Group on Facebook Main Wellglade series includes Trentbarton, TM Travel, Notts+Derby and Kinchbus No. Registration Chassis Bodywork Seating Operator Depot Livery Notes 1 YJ07EFR Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 2 YJ07EFS Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 3 YJ07EFT Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 4 YJ07EFU Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 5 YJ07EFV Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 6 YJ07EFW Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 7 YJ07EFX Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Kinchbus 8 YN56FDA Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 9 YN56FDU Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 10 YN56FDZ Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 29 W467BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 30 W474BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 31 W475BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 32 W477BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 33 W291PFS Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H45/30F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 34 W292PFS Volvo B7TL Plaxton President -

Student Information Booklet 2021

Student Information Booklet 2021 Dear Students We are so excited to be moving into our new building in September 2021. This information leaflet is designed to introduce you to some key aspects of the building and our move. As you will have seen from our monthly updates, the building development is making great progress and our first group of student building ambassadors are visiting the site this term. Whilst our new building is a fantastic opportunity it is also a huge responsibility and there is some key information in this booklet that should help make our move as smooth as possible. Please do take some time to read through this information with your form tutor and parents. With our new site there will be changes for everyone to get used to. We hope that this guide helps with any questions you may have and any planning you may have to do with travel arrangements. Each form group has two building ambassador that will be your key contact with all aspects relating to the building. They will be there to support you but also remember that all staff are always here to help you with all aspects of school life. For many of you, this new building has felt like a long wait. I also thank you for your patience and encouragement over the years. We look forward to welcoming you into the building and further developing and demonstrating our FAITH values as we take this next step together as Derby Cathedral School. Yours faithfully Mrs J. Brown Headteacher Location The address of our new site is: Derby Cathedral School Great Northern Road Derby DE1 1LR It is situated on Great Northern Road close to the junction with Uttoxeter Road. -

Fully Subsidised Services Comments Roberts 120 • Only Service That

167 APPENDIX I INFORMAL CONSULTATION RESPONSES County Council Comments - Fully Subsidised Services Roberts 120 • Only service that goes to Bradgate Park • Service needed by elderly people in Newtown Linford and Stanton under Bardon who would be completely isolated if removed • Bus service also used by elderly in Markfield Court (Retirement Village) and removal will isolate and limit independence of residents • Provides link for villagers to amenities • No other bus service between Anstey and Markfield • Many service users in villages cannot drive and/or do not have a car • Service also used to visit friends, family and relatives • Walking from the main A511 is highly inconvenient and unsafe • Bus service to Ratby Lane enables many vulnerable people to benefit educational, social and religious activities • Many residents both young and old depend on the service for work; further education as well as other daily activities which can’t be done in small rural villages; to lose this service would have a detrimental impact on many residents • Markfield Nursing Care Home will continue to provide care for people with neuro disabilities and Roberts 120 will be used by staff, residents and visitors • Service is vital for residents of Markfield Court Retirement Village for retaining independence, shopping, visiting friends/relatives and medical appointments • Pressure on parking in Newtown Linford already considerable and removing service will be detrimental to non-drivers in village and scheme which will encourage more people to use service Centrebus -

What Is Integrated Ticketing?

Integrated Ticketing Strategy and Delivery Plan INDEX • Executive summary • Background • Current position of Ticketing In Nottinghamshire • Scheme Design, Timeline, Promotion and Governance • Consultation What is Integrated Ticketing? Multi-operator integrated ticketing is an important aspect of realising the County Council’s vision for a better bus service. It makes using buses more convenient, reliable and flexible for passengers, allowing them to use services from a range of operators. Executive Summary The bus network is important as a means to providing accessibility and transport choice to the community, delivering benefits to society including accessibility, transport choice, congestion management, CO2 reductions and helps to stimulate economic growth. The 1985 Transport Act set the scene for the deregulation of the bus industry, and therefore it is essential that bus operations are well integrated and affordable. This Strategy sets out the importance of integrated ticketing to passengers to help sustain a strong and vibrant commercial network. It explains how we move forward towards transport integration in the context of the Nottinghamshire County Council Strategic Plan (2014-2018) 1, Local Transport Plan (up to 2026) 2 and Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) 3 priorities. This will include the legal framework, government policy and guidance and outlines from 2014-2026 Nottinghamshire County Council’s vision for Integrated Ticketing. This document sets out how Integrated Ticketing will be delivered once scheme design, price, partnership arrangements and funding is secured, with an ambitious timeline for implementation. Background The use of public transport is important to tackle congestion, rising CO2 levels and improving access to employment, training, health, leisure and shopping opportunities. -

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (New Entries First with Older Entries Retained Underneath)

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (new entries first with older entries retained underneath) Now go back to: Home Page Introduction or on to: The Best Timetables of the British Isles Summary of the use of the 24-hour clock Links Section English Counties Welsh Counties, Scottish Councils, Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland, Channel Islands and Isle of Man Bus Operators in the British Isles Rail Operators in the British Isles SEPTEMBER 25 2021 – FIRST RAIL RENEWS SPONSORSHIP I am pleased to announce that First Rail (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-rail.aspx) has renewed its sponsorship of my National Rail Passenger Operators' map and the Rail section of this site, thereby covering GWR, Hull Trains, Lumo, SWR and TransPennine Express, as well as being a partner in the Avanti West Coast franchise. This coincides with the 50th edition of the map, published today with an October date to reflect the start of Lumo operations. I am very grateful for their support – not least in that First Bus (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-bus.aspx) is already a sponsor of this website. JULY 01 2021 – THE FIRST 2021 WELSH AUTHORITY TIMETABLE Whilst a number of authorities in SW England have produced excellent summer timetable books – indeed some produced them throughout the pandemic – for a country that relies heavily on tourism Wales is doing an utterly pathetic job, with most of the areas that used to have good books simply saying they don’t expect to publish anything until the autumn or the winter – or, indeed that they have no idea when they’ll re-start (see the entries in Welsh Counties section). -

Derby Retail Study

Imperial West Imperial Derby Retail Study SophosSophos International International Curtins 56 The Ropewalk Nottingham NG1 5DW T. 0115 941 5551 E. [email protected] CIVILS & STRUCTURES • TRANSPORT PLANNING • ENVIRONMENTAL • INFRASTRUCTURE • GEOTECHNICAL • CONSERVATION & HERITAGE • PRINCIPAL DESIGNER Birmingham • Bristol • Cambridge • Cardiff • Douglas • Dublin • Edinburgh • Glasgow • Kendal • Leeds • Liverpool • London • Manchester • Nottingham TPNO66625-CUR-00-XX-RP-TP-00001 Derby Retail Study Zone 1 – Derby City Centre Accessibility & Infrastructure Appraisal Control Sheet Rev Description Issued by Checked Date 00 Draft SS MP 01/10/2018 01 Final SS MP 13/05/2019 This report has been prepared for the sole benefit, use, and information for the client. The liability of Curtins Consulting Limited with respect to the information contained in the report will not extend to any third party. Author Signature Date Sarah Strauther MCIHT 13 May 2019 Senior Transport Planner Reviewed Signature Date Matt Price BSc (Hons) MSc TPP FCIHT 13 May 2019 Associate Authorised Signature Date Matt Price BSc (Hons) MSc TPP FCIHT 13 May 2019 Associate Rev P01 | Copyright © 2019 Curtins Consulting Ltd Page i TPNO66625-CUR-00-XX-RP-TP-00001 Derby Retail Study Zone 1 – Derby City Centre Accessibility & Infrastructure Appraisal Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Purpose of This Report .............................................................................................................. -

Current Timetable

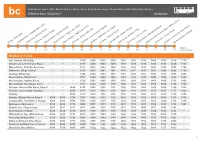

Derby - Ilkeston - Heanor - Sutton - Mansfield via Derby - Stanley - Ilkeston - Ilkeston Hospital - Heanor - Sherwood Business Park - Kirkby - Sutton - Mansfield bc Effective from: 02/02/2021 trentbarton Derby, MorledgeChaddesden,Oakwood, Chaddesden Stanley,Morley Lane Road StationWest Hallam,RoadWest Station Hallam, WestRoad High Hallam, LaneIlkeston, HighWest LaneWharncliffeIlkeston, East Community RdShipley, Hassock HospitalHeanor, Lane WilmotLangley North Street Mill,Eastwood, Station Road Brinsley,Kelham Way ChurchUnderwood, LaneSherwood Mansfield Annesley,Business Road Park, DerbyKirkby Willow RoadIn Ashfield,Mansfield Drive Ellis Bus Street Station Approx. 8 16 21 24 26 30 35 43 46 51 55 61 66 69 74 81 88 114 journey times Monday to Friday Bus Station, Morledge ··· ··· ··· 0705 0830 0930 1030 1130 1230 1330 1430 1530 1630 1735 Chaddesden, Richmond Road ··· ··· ··· 0713 0838 0939 1039 1139 1239 1339 1439 1539 1639 1744 Maine Drive, Chaddesden Lane ··· ··· ··· 0716 0841 0942 1042 1142 1242 1342 1442 1543 1643 1748 Oakwood, Kings Corner ··· ··· ··· 0720 0845 0947 1047 1147 1247 1347 1447 1548 1648 1753 Stanley, White Hart ··· ··· ··· 0724 0849 0951 1051 1151 1251 1351 1451 1555 1655 1800 West Hallem, White Hart ··· ··· ··· 0727 0854 0954 1054 1154 1254 1354 1454 1558 1658 1803 West Hallam, Station Road ··· ··· ··· 0729 0856 0956 1056 1156 1256 1356 1456 1600 1700 1805 West Hallam, Newdigate Arms ··· ··· ··· 0733 0900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1604 1704 1809 Ilkeston, Wharncliffe Road, Stop C ··· ··· 0648 0738 0905 1005 1105 1205 -

JOURNAL Autumn 2016 Conference Page 9 No

The Roads and Road Transport History Association Contents Evolution of Road Passenger Page 1 Transport Branding Letter to the Editor Page 7 JOURNAL Autumn 2016 Conference Page 9 No. 87 Reviews Page 13 February 2017 www.rrtha.org.uk Journal Archive Page 19 Little-Known Transport Heroes Page 21 Coach’ from the Black Swan, Holborn, London) or, The Evolution of Road Passenger where competing services dictated product Transport Heritage Branding differentiation, by name. Stirring names were often selected, such as Sovereign, Tally Ho!, or Enterprise. Martin Higginson This paper is based on presentations by the author at a York University Business History Workshop on 16 September 2016 and at the R&RTHA Coventry meeting on 29 October2016 Since the earliest days, transport operators have sought to distinguish their offerings from those of other providers. At its most local level, the operator would be known personally to his customers: Farmer Giles’ cart taking local passengers to the market along with his own produce or livestock. Today, some customers may prefer their local taxi firm, whose drivers they know by name and trust. Traditionally, country bus drivers and their regular passengers know one another. When passenger transport operations become more removed from the communities they serve and more impersonal, for example inter-town services, alternative means of attracting custom become necessary. This is where marketing and branding begin. Some of the first York Four Days Stagecoach advertisement, 1706 examples were stagecoaches: fast, publicly available services benefiting from turnpikes and other road Source: Tom Bradley, The Old Coaching Days in Yorkshire, improvements. Departures were from inns, whose Yorkshire Conservative Newspaper Co (“The Yorkshire Post”), Leeds, 1889, which also contains a 28-page names were advertised in press announcements alphabetical list of coach services in the area, from detailing routes, times and fares. -

Chesterfield Station I Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local Area Map

Chesterfield Station i Onward Travel Information Buses and Taxis Local area map Chesterfield is a PlusBus area Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA PlusBus is a discount price ‘bus pass’ that you buy with Rail replacement buses and coaches depart from the front of the station. your train ticket. It gives you unlimited bus travel around your chosen town, on participating buses. Visit www.plusbus.info Main destinations by bus (Data correct at April 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP 54, X54 A 2, 2A, 90 K3 Renishaw 70, 70A, 72 C 55, 55A, X55, 'The { - Walton Park Estate 2, 2A, 2B(Eve/ { Sheepbridge 14, 43, 44 V Alfreton ^ New Beetwell St New Beetwell St Comet' Sun), 90 Sheffield ^ 43, 44, X17 T2 K3 56 Coach Station { - Yew Tree Estate 90 Shirebrook 82 K2 78 A Clay Cross 51, 54, X54 A 54, X54 A Arkwright Town Shirland 82, 83 K2 Clowne 77 C 'The Comet' New Beetwell St Bakewell (Change here for Buxton) 170# New Beetwell St Creswell 77 C Spring Vale Estate 90 T1 V Barlborough 77 C 14, 43, 44 T2 V 70, 70A, 72, 74, Dronfield ^ C Barrow Hill (for Railway Centre) 90 T1 V 16 L2 Staveley 77 Baslow (Change here for Chatsworth Duckmanton 74 C 78 A 170## New Beetwell St House) East Midlands Designer Outlet 54, X54 A 70, 70A, 72, 74, { Tapton C Bolsover 82, 83 K2 Eckington 70, 70A C 77 78 A Glapwell 'Pronto' Coach Station Temple Normanton 56, 'Pronto' Coach Station { Brimington 70, 70A, 72, 74, Coach -

AMBERLINE Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

AMBERLINE bus time schedule & line map AMBERLINE Hucknall - Eastwood - Heanor - Derby View In Website Mode The AMBERLINE bus line (Hucknall - Eastwood - Heanor - Derby) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Derby: 6:39 AM - 5:00 PM (2) Hucknall: 6:15 AM - 4:35 PM (3) Langley Mill: 6:10 PM (4) Langley Mill: 5:35 PM - 6:35 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest AMBERLINE bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next AMBERLINE bus arriving. Direction: Derby AMBERLINE bus Time Schedule 111 stops Derby Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:51 AM - 7:51 PM Monday 6:39 AM - 5:00 PM Market Place, Hucknall Baker Street, Hucknall Tuesday 6:39 AM - 5:00 PM Bus Link, Hucknall Wednesday 6:39 AM - 5:00 PM 44-46 High Street, Hucknall Thursday 6:39 AM - 5:00 PM Hanson Crescent, Hucknall Friday 6:39 AM - 5:00 PM 3 Watnall Road, Hucknall Saturday 6:39 AM - 5:00 PM Health Centre, Hucknall 108-110 Watnall Road, Hucknall Long Hill Rise, Hazelgrove AMBERLINE bus Info High Leys Road, Hazelgrove Direction: Derby Stops: 111 Football Ground, Ruffs Estate Trip Duration: 90 min Line Summary: Market Place, Hucknall, Bus Link, Ruffs Drive, Ruffs Estate Hucknall, Hanson Crescent, Hucknall, Health Centre, Hucknall, Long Hill Rise, Hazelgrove, High Leys Road, Ashurst Grove, Westville Hazelgrove, Football Ground, Ruffs Estate, Ruffs Drive, Ruffs Estate, Ashurst Grove, Westville, Kingsway Road, Westville Kingsway Road, Westville, Trent Drive, Westville, Long Lane, Hucknall, Long Lane, Hucknall, Long Lane, Trent Drive, Westville -

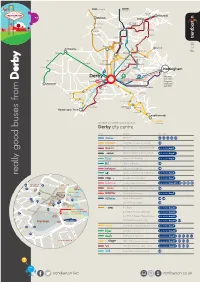

Really Good Buses from Derby E O T C S O ? M a K

to Bakewell to Chesterfield King’s Mill Hospital Mansfield Matlock Sutton East Midlands Matlock Bath Designer Outlet Cromford Alfreton Kirkby Middleton Pinxton Wirksworth Annesley Swanwick Heage Ripley Belper Brinsley Ashbourne Aldercar Hucknall Eastwood Mayfield Kilburn Heanor Ilkeston non-stop Hospital Kimberley Smalley Cotmanhay Ellastone Dueld Brailsford West Hallam Little Eaton Ilkeston Stanley Denstone non-stop Allestree Kirk Hallam QMC Rocester Nottingham Oakwood non-stop Sandiacre Stapleford buses to Beeston Bingham Derby non-stop Derby Royal Derby Spondon non-stop Calverton Mickleover Borrowash Chilwell Cotgrave Keyworth Uttoxeter Draycott Breaston Littleover Radclie Alvaston Long Eaton m Etwall Heatherton Hilton Findern Old Sawley Hatton Shardlow o non-stop r Tutbury Willington f Rolleston Castle Donington Kegworth Stretton Repton s Newton Solney East Midlands Airport Diseworth Burton upon Trent e Long Whatton Hathern Loughborough s u where to catch your bus in to Leicester b Derby city centre route towards bus stop d Allestree B13 B14 B16 B1 C7 o Little Eaton, Heanor & Hucknall C2 o Ilkeston, Heanor, Kirkby & Mansfield bus station bay 3 g Alfreton, Clay Cross & Chesterfield bus station bay 4 y Ilkeston & Cotmanhay bus station bay 9 l l Heanor & Alfreton C3 a Littleover & Heatheron A9 e Sandiacre, Stapleford & Nottingham bus station bay 6 r T S Long Eaton & Nottingham bus station bay 7 N E E U Q E S F T N M R A Royal Hospital, Mickleover bus station bays 20 & 21 B3 B4 B9 A R I Y L A museum & ’S B13 G cathedral B11 R A D TE art gallery -

Travel Information

WELCOME A BIG BOX TRAVEL INFORMATION WELCOME A BIG BOX WELCOME TO WELCOME Starting a new job is the perfect optionstime and to explorethis pack your has travel all the information you need to decide BUS & TRAIN how to commute to work. CAR SHARING WALKING & CYCLING CONTACTS WELCOME BUSES & TRAINS BY USING PUBLIC TRANSPORT, YOU COULD… A BIG BOX DE-STRESS YOUR COMMUTE AND MAKE THE BEST USE SAVE MONEY OF YOUR TIME on the cost of travel with TAKE THE DRIVING Read a book, listen to music a range of saver tickets or call a friend DETOX. SIT BACK, RELAX, COMMUTE BUS & TRAIN BY BUS OR TRAIN. CAR SHARING STAY CONNECTED REDUCE YOUR Catch up on emails or scroll CARBON FOOTPRINT through social media and lower your CO2 emissions WALKING & CYCLING CONTACTS MAKE EVERYONE’S DIRECT SERVICES JOURNEY QUICKER Catch a bus straight from A busy bus replaces 40 Nottingham, Leicester, cars on the road and trains Loughborough and Derby to can reduce that even further East Midlands Gateway WELCOME BUSES & TRAINS A BIG BOX BUS DERBY S S Y NOTTINGHAM TEST RUN If you’re a new employee and you’d like to try commuting to work by bus, speak to your employer as you might be eligible J2A for a ‘taster’ bus ticket. BE A SAVVY SAVER If you’re travelling regularly by bus, why not consider a S LOCKINGTON season ticket? It’ll not only make the cost of the commute DONINGTON cheaper, but it means you won’t always be looking for change for the bus! J2 GET A PAY-AS-YOU-GO ‘Mango Card’ or ‘Kinchkard’ to top up and save.