2015 National Fares Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

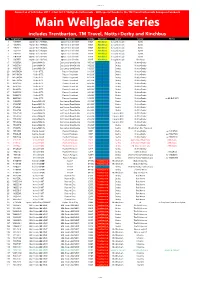

Wellglade Series Includes Trentbarton, TM Travel, Notts+Derby and Kinchbus No

Main series Correct as of 6 October 2017 • Fleet list © Wellglade Enthusiasts • With special thanks to the TM Travel Enthusiasts Group on Facebook Main Wellglade series includes Trentbarton, TM Travel, Notts+Derby and Kinchbus No. Registration Chassis Bodywork Seating Operator Depot Livery Notes 1 YJ07EFR Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 2 YJ07EFS Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 3 YJ07EFT Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 4 YJ07EFU Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 5 YJ07EFV Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 6 YJ07EFW Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Sprint 7 YJ07EFX Optare Solo M950SL Optare Solo Slimline B32F Kinchbus Loughborough Kinchbus 8 YN56FDA Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 9 YN56FDU Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 10 YN56FDZ Scania N94UD East Lancs OmniDekka H45/32F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 29 W467BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 30 W474BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 31 W475BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 32 W477BCW Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H41/24F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 33 W291PFS Volvo B7TL Plaxton President H45/30F Notts+Derby Derby Notts+Derby 34 W292PFS Volvo B7TL Plaxton President -

Student Information Booklet 2021

Student Information Booklet 2021 Dear Students We are so excited to be moving into our new building in September 2021. This information leaflet is designed to introduce you to some key aspects of the building and our move. As you will have seen from our monthly updates, the building development is making great progress and our first group of student building ambassadors are visiting the site this term. Whilst our new building is a fantastic opportunity it is also a huge responsibility and there is some key information in this booklet that should help make our move as smooth as possible. Please do take some time to read through this information with your form tutor and parents. With our new site there will be changes for everyone to get used to. We hope that this guide helps with any questions you may have and any planning you may have to do with travel arrangements. Each form group has two building ambassador that will be your key contact with all aspects relating to the building. They will be there to support you but also remember that all staff are always here to help you with all aspects of school life. For many of you, this new building has felt like a long wait. I also thank you for your patience and encouragement over the years. We look forward to welcoming you into the building and further developing and demonstrating our FAITH values as we take this next step together as Derby Cathedral School. Yours faithfully Mrs J. Brown Headteacher Location The address of our new site is: Derby Cathedral School Great Northern Road Derby DE1 1LR It is situated on Great Northern Road close to the junction with Uttoxeter Road. -

English Counties

ENGLISH COUNTIES See also the Links section for additional web sites for many areas UPDATED 23/09/21 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] TRAVELINE SITES FOR ENGLAND GB National Traveline: www.traveline.info More-detailed local options: Traveline for Greater London: www.tfl.gov.uk Traveline for the North East: https://websites.durham.gov.uk/traveline/traveline- plan-your-journey.html Traveline for the South West: www.travelinesw.com Traveline for the West & East Midlands: www.travelinemidlands.co.uk Black enquiry line numbers indicate a full timetable service; red numbers imply the facility is only for general information, including requesting timetables. Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that a county or council might be showing on its web site. ENGLAND BEDFORDSHIRE BEDFORD Borough Council No publications Public Transport Team, Transport Operations Borough Hall, Cauldwell Street, Bedford MK42 9AP Tel: 01234 228337 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] www.bedford.gov.uk/transport_and_streets/public_transport.aspx COUNTY ENQUIRY LINE: 01234 228337 (0800-1730 M-Th; 0800-1700 FO) PRINCIPAL OPERATORS & ENQUIRY LINES: Grant Palmer (01525 719719); Stagecoach East (01234 220030); Uno (01707 255764) CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE Council No publications Public Transport, Priory House, Monks Walk Chicksands, Shefford SG17 5TQ Tel: 0300 3008078 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] -

Fully Subsidised Services Comments Roberts 120 • Only Service That

167 APPENDIX I INFORMAL CONSULTATION RESPONSES County Council Comments - Fully Subsidised Services Roberts 120 • Only service that goes to Bradgate Park • Service needed by elderly people in Newtown Linford and Stanton under Bardon who would be completely isolated if removed • Bus service also used by elderly in Markfield Court (Retirement Village) and removal will isolate and limit independence of residents • Provides link for villagers to amenities • No other bus service between Anstey and Markfield • Many service users in villages cannot drive and/or do not have a car • Service also used to visit friends, family and relatives • Walking from the main A511 is highly inconvenient and unsafe • Bus service to Ratby Lane enables many vulnerable people to benefit educational, social and religious activities • Many residents both young and old depend on the service for work; further education as well as other daily activities which can’t be done in small rural villages; to lose this service would have a detrimental impact on many residents • Markfield Nursing Care Home will continue to provide care for people with neuro disabilities and Roberts 120 will be used by staff, residents and visitors • Service is vital for residents of Markfield Court Retirement Village for retaining independence, shopping, visiting friends/relatives and medical appointments • Pressure on parking in Newtown Linford already considerable and removing service will be detrimental to non-drivers in village and scheme which will encourage more people to use service Centrebus -

Notices and Proceedings for the North East of Englanf

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2363 PUBLICATION DATE: 22/03/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 12/04/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/03/2019 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. Our website includes details of all applications listed in this booklet. The website address is: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners Copies of Notices and Proceedings can be inspected free of charge at the Office of the Traffic Commissioner in Leeds. -

Diamond, Hallmark Diamond Bus Limited; Shady Lane Property Limited, Hallbridge Way, Tipton Road, Tividale, West Midlands, B69 3HW

Midlands Diamond PD0001374, PD1028090 Diamond, Hallmark Diamond Bus Limited; Shady Lane Property Limited, Hallbridge Way, Tipton Road, Tividale, West Midlands, B69 3HW Part of the Rotala Group plc. Depots: Diamond Kidderminster Island Drive, Kidderminster, Worcestershire, DY10 1EZ Redditch Plymouth Road, Redditch, Worcestershire, B97 4PA Tamworth Common Barn Farm, Tamworth Road, Hopwas, Lichfield, Staffordshire, WS14 9PX Tividale Cross Quays Business Park, Hallbridge Way, Tipton Road, Tividale, West Midlands, B69 3HW Store: John’s Lane, Tividale, West Midlands, DY4 7PS Chassis Type: Optare Solo M780 Body Type: Optare Solo Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20010 YJ56AUA B28F 2006 Tividale Diamond DUN, 2012 Previous Owners: DUN, 2012: Dunn-Line, 2012 Chassis Type: Optare Solo M960SR Body Type: Optare Solo SR Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20014 YJ10MFY B30F 2010 Redditch Diamond 20015 YJ10MFX B30F 2010 Redditch Diamond Chassis Type: Alexander-Dennis Dart SLF Body Type: Alexander-Dennis Pointer Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20023 SN05HDD B29F 2005 Tividale Diamond DVB, 2010 Previous Owners: DVB, 2010: Davidson Buses, 2010 Chassis Type: Optare Solo M960SR Body Type: Optare Solo SR Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20027 YJ10MFZ B30F 2010 Redditch Diamond Chassis Type: Optare Solo M790SE Body Type: Optare Solo SE Fleet No: Reg No: Seating: New: Depot: Livery: Prev Owner: 20050 YJ60KBZ B27F 2010 Tividale Diamond RGL, 2017 20051 YJ60KHA B27F 2010 Tividale Diamond RGL, 2017 20052 YJ60KHB B27F 2010 Kidderminster Diamond RGL, 2017 20053 YJ60KHC B27F 2010 Tividale Diamond RGL, 2017 Previous Owners: RGL, 2017: Regal Busways, 2017 Fleet list template © Copyright 2021 ukbuses.co.uk. -

Ashby De La Zouch

A Ashby-de-la-Zouch Bus map & guide January 2021 B FREQUENCY Service Operator(s) Route Monday – Monday – Sunday and Saturday Daytime Saturday Evenings Bank Holidays East Midlands Airport (EMA) - ASHBY-DE-LA-ZOUCH - Woodville - Swadlincote - 9 Midland Classic hourly hourly hourly Burton-upon-Trent (Queen's Hospital) 19 Midland Classic ASHBY-DE-LA-ZOUCH - Measham - Swadlincote - Burton-upon-Trent hourly no service no service 29 Arriva Coalville - ASHBY-DE-LA-ZOUCH - Swadlincote hourly no service hourly 29A Arriva Coalville - ASHBY-DE-LA-ZOUCH - Swadlincote hourly no service no service 129 Paul S. Winson ASHBY-DE-LA-ZOUCH - Loughborough infrequent no service no service Underlined services are supported by Leicestershire County Council During the COVID-19 pandemic service frequencies may be subject to short notice alteration. Please check the operator’s website for the most up to date bus timetables. For town centre Smisby Road stops see over A511 Map not to scale Supermarket Woodcote 129 9 29/29A Primary School Health Centre Burton Road 129 Ivanhoe 29/29A A511 College Marlborough Way Nottingham Road 29/29A Bishop 29/29A Hall Ashby Road Primary Wood Street School Ashby North Street B School urton Road Market Street Churchill Close Ashby 9 Castle 19 Abbey Drive 29/29A South Street Ashby School Lewis Boarding de si Moira Road Charlton House A42 d Station Road o Village o Ashby Hill Top W Primary School Beaumont Leicester Road Avenue Ridgway Road Baker Tamworth Road Avenue Staley Avenue Lower A42 Willesley Packington Primary School Road 19 Measham Road Railway Line Services operate in direction shown This map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown Copyright. -

Mr C Booth V Transdev Blazefield Ltd: 1805268/2019

Case No: 1805268/2019 Code V EMPLOYMENT TRIBUNALS Claimant: Mr C Booth Respondent: Transdev Blazefield Ltd Heard at: Leeds (by CVP) On: 1-2 September 2020 Before: Employment Judge Parkin Representation Claimant: Mr A Macmillan, Counsel Respondent: Ms R Jones, Counsel RESERVED JUDGMENT The Judgment of the Tribunal is that: 1) The claimant was fairly dismissed by the respondent and his unfair dismissal claim is dismissed; and 2) The claimant was not wrongfully dismissed by the respondent and his breach of contract claim is dismissed. REASONS 1 The claim and response 1.1 By a claim form presented on 8 October 2019, the claimant claimed unfair dismissal and wrongful dismissal from his post as Transport Manager with the respondent, based at York and Malton, on 30 May 2019. He set out that he had been dismissed summarily for three counts of alleged gross negligence consisting of allowing a bus to be used in service without an MOT certificate, failing to follow the advice of a health and safety professional in respect of a student’s work experience and cleanliness of the depot and bus fleet. He maintained the respondent did not genuinely believe he was guilty of the allegations and had failed to adequately investigate them and to treat him consistently with other employees in similar circumstances. Although he accepted the bus was used in service without 1 Case No: 1805268/2019 Code V an MOT certificate, he maintained the respondent failed to investigate the extenuating circumstances not least its one off nature and the fact it had been transferred from Burnley and so had not been included in the MOT plan and that he did follow the advice of a health and safety professional in respect of a student’s work experience. -

Minutes of Marches Growth Hub Steering Group 19 March 2020

Minutes of Marches Growth Hub Steering Group 19 March 2020 Present Paul Hinkins PH Marches Growth Hub Chair, Marches LEP Board Deputy Chair Oliver Hindle OH Marches Are Lead – Cities and Local Growth Unit, BEIS Frank Myers MBE FM LEP Board Member, Chair of Herefordshire Business Board – Director MCP Systems Consultants Ltd Colin Preece CP Marches Skills Provider Network Executive Officer Amy Bould AB Marches LEP PR & Marketing, Director Be Bold Media Ltd Maisy Owen MO Chamber Member - Chair of Members Committee, Director MO Management Consultancy Ltd Beth Heath BH Shropshire Business Board Representative, Director Shropshire Festivals, Director Shropshire Think Tank Hollie Whittles HW Federation of Small Businesses - Area Lead Shropshire, Herefordshire and Worcestershire and Director Fragglesworks Richard Nicklin PB University of Wolverhampton, External Relations Deputy Director – Business Engagement Steve Havins SH D epartment for International Trade, Head of Business Development & Partnerships Nick Webster NW Herefordshire Council - Economic Development Manager Delia Yapp DY Shropshire Council, Key Accounts and Investment Manager Yasmin Sulaman YS Marches LEP Business Support Project Officer Kathryn Jones LP Marches LEP Partnership Manager Apologies: Matt Potts - Shropshire Council Business Growth and Inward Investment Manager Katharine Clough – University of Wolverhampton, Director – External Relations Colin Thaw - Marches Skills Provider Network Chair, Director SBC Training Not Present: Kathy Mulholland - Telford & Wrekin Council - Inward Investment & Business Support Service Delivery Manager ITEM ACTION 1. Welcome and Introductions PH welcomed Steering Group (SG) Members to the telephone call meeting and highlighted new members to the group. Roundtable introductions were followed by YS confirming apologies. 2. Declarations of Member Interest No declarations of interest were noted in relation to any agenda item. -

ORGANISATION ADDRESS NAME IF KNOWN EAST NORTHANTS COUNCIL East Northamptonshire House, Cedar Dr, Mike Burton – ENC Planning Thrapston, Kettering NN14 4LZ

ORGANISATION ADDRESS NAME IF KNOWN EAST NORTHANTS COUNCIL East Northamptonshire House, Cedar Dr, Mike Burton – ENC Planning Thrapston, Kettering NN14 4LZ NATURAL ENGLAND Natural England Andrew Sells – Chairman Block B, Government Buildings, Whittington Road Julie Danby Team Leader- Worcester [email protected] WR5 2LQ HISTORIC ENGLAND 2nd floor Windsor House Cliftonville Northampton NN1 5BE HEADMASTER Brigstock Latham's CE Primary School, Latham Mr Nick Garley (Headteacher) BRIGSTOCK SCHOOL Street, Brigstock, Kettering Northants NN14 3HD HEAD OF GOVERNORS c/o Brigstock Latham's CE Primary School, Latham Mr Tim Cullinan BRIGSTOCK SCHOOL Street, Brigstock, Mrs Abigail Marsden-Findlay - Kettering Northants NN14 3HD [email protected] DIOCESAN BOARD OF FINANCE The Palace/Minster Precincts, Peterborough PE1 1YB NENE VALLEY CATCHMENT PARTNERSHIP The Business Exchange Rockingham Rd Kettering NN16 8JX ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Waterside House Or Waterside North Lincoln Lincolnshire LN2 5HA Nene House Ketteriing Northants NN15 6JQ CLINICAL COMMISSIONING NHS Nene Clinical Commissioning Group Francis Crick House Summerhouse Road Moulton Park Northampton NN3 6BF WILDLIFE TRUST Lings House, off Lings Way Billing Lings Northampton NN3 8BE HOUSING ASSOCIATIONS Spire Homes 1 Crown Court, Crown Way, Rushden, Northamptonshire NN10 6BS RURAL HOUSING ASSOCIATION [email protected] Neil Gilliver ROCKINGHAM FOREST HOUSING ASSOCIATION [email protected] POLICE – East Northants North Police station Oundle Police Station Glapthorn -

Local Sustainable Transport Fund Projects - Summaries

Local Sustainable Transport Fund Projects - Summaries KEY TERMS Tranche 1 Small projects (£5m or less), announced July 2011 Key Component Small projects (£5m or less) from teams that also planned to submit a large project proposal, announced July 2011 Tranche 2 Small projects receiving £5m or less, announced in May, June and Sept 2012 Large Projects Projects receiving between £5m and £50m, announced in June 2012 Bedford Borough Council Access to Stations (£4.803m) – Tranche 2 www.bedford.gov.uk and www.sustrans.org.uk Bedford Borough Council is the lead authority for this project, working in partnership with Sustrans, Buckinghamshire County Council, Cornwall Council, Devon County Council, Plymouth City Council, Swindon Borough Council, Derbyshire County Council and Warwickshire County Council. Access to Stations is a portfolio of specifically tailored projects which address local barriers to increase walking and cycling access for 20 stations. Benefits include improved access to surrounding employment, training and retail opportunities, as well as improved air quality, safety and health for people who travel more actively. By improving door-to-door journeys, this project aims to achieve an overall shift from car travel to rail for entire journeys. Birmingham City Council Bike North Birmingham (£4.123m) – Tranche 1 www.birmingham.gov.uk/bikenorthbirmingham Birmingham City Council’s project provides cycling infrastructure for key employment hubs in Sutton Coldfield, which will address a well-recognised problem of high CO2 emissions within the region. The project will tackle the current reliance on the private car for short trips by improving integration between existing transport networks and hubs. 1 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council BwD CONNECT Project (£1.452m) - Tranche 2 www.blackburn.gov.uk/transportplan The BwD CONNECT project is a campaign combining travel behaviour change with the provision of improved walking, cycling and public transport infrastructure. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Calderdale District Consultation

CALDERDALE DISTRICT CONSULTATION SUB-COMMITTEE MEETING TO BE HELD AT 5.00 PM ON TUESDAY 9 JANUARY 2018 IN THE MAIN HALL, THE KINGS CENTRE, HALIFAX, HX2 2TS A G E N D A 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2.2. ENCOURAGING YOUNG PEOPLE TO USE BUSES This will be a presentation provided by a representative from the West Yorkshire Combined Authority. 3.3. OPERATOR UPDATES This will be presented by representatives from the bus and rail operators. 4.4. MINUTES FROM THE MEETING HELD ON 10 OCTOBER 2017 Copy attached. (Pages 1 - 4) 5.5. INFORMATION REPORT This will provide the opportunity for questions to be raised from the floor with a focus on matters of wider interest. (Pages 5 - 10) 6.6. OPEN FORUM This will provide the opportunity for questions to be raised from the floor with a focus on matters of wider interest. This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 4 MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE CALDERDALE DISTRICT CONSULTATION SUB-COMMITTEE HELD ON TUESDAY, 10 OCTOBER 2017 AT COMMITTEE ROOM B, TOWN HALL, CROSSLEY STREET, HALIFAX, HX1 1UJ Present: Councillor Daniel Sutherland (Chair) Transport Committee Councillor Peter Caffrey Transport Committee Reid Anderson (Public Representative) Public Representative Meg Gillet (Public Representative) Public Representative Myra James (Public Representative) Public Representative Zaheer Khalil (Public Representative) Public Representative Peter Melling (Public Representative) Public Representative John Myddelton (Public Representative) Public Representative John Sheppard (Public Representative) Public Representative Kate Smyth (Public Representative) Public Representative John Whiteley (Public Representative) Public Representative Geoff Wood (Public Representative) Public Representative In attendance: Mark Fenwick Arriva Yorkshire Councillor Paul Bellenger Calderdale Council Jenny Marshall Calderdale Council Peter Stubbs Calderdale Council Daniel Weir Calderdale Council Stuart Fillingham First Group Oliver Howarth First Group Pete Myers Northern Elliot Day Yorkshire Tiger Diane Groom WYCA Erica Ward WYCA Andrew Atack WYCA 1.